Marge Frantz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marge Frantz

|

|

|---|---|

| Born |

Margaret Louise Gelders

June 18, 1922 |

| Died | October 16, 2015 (aged 93) |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Margie Gelders, Margaret Gelders Frantz |

| Occupation | activist, academic |

| Years active | 1937–1999 |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives | Blanche Hartman (sister) Emma Gelders Sterne (aunt) Nina Hartley (niece) |

Marge Frantz (born Margaret Gelders; June 18, 1922 – October 16, 2015) was an American activist and a university teacher. She was one of the first people to teach women's studies classes in the United States.

Marge was born in Birmingham, Alabama. From a young age, she got involved in causes that aimed to make society better. She helped organize workers, fought for equal rights for all people, and worked to stop the poll tax that kept some women from voting.

In the 1940s, she worked for a union and then for a group called the Southern Conference for Human Welfare. She even edited their newspaper, Southern Patriot. Because of her activism, a government group called the House Un-American Activities Committee investigated her. In 1950, she and her husband moved to California.

Marge continued her activism in California. She protested against nuclear weapon testing and supported people who were accused of spying. In 1969, she left her job at the University of California, Berkeley after police used violence against student protesters. She then became a student herself. She earned her bachelor's degree in 1972 and later moved to the University of California, Santa Cruz for her PhD. At UC Santa Cruz, she helped start the Women's Studies Department. She taught there from 1973 to 1999 and won two awards for her teaching. Her life as an activist was shown in the 1983 movie, Seeing Red.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Margaret Louise "Margie" Gelders was born on June 18, 1922, in Birmingham, Alabama. Her parents were Esther Josephine Gelders and Joseph Gelders. Her father taught physics at the University of Alabama. He also became involved in the Communist Party, helped organize workers, and fought for racial justice in the South.

When she was 13, Margie joined the Young Communist League, a youth group with certain political ideas. She often traveled with her father to support causes they believed in. From a young age, she took part in protest marches and rallies. She worked to end the poll tax, which was a fee people had to pay to vote.

In 1936, her father was badly beaten because of his civil rights work. This showed Margie the dangers of being an activist. But it did not stop her from following in his footsteps. After finishing Phillips High School in Birmingham in 1938, she studied at Radcliffe College for two years.

While at college, Margie worked for the Massachusetts chapter of the League of Women Voters. This group helps people vote and understand politics. In 1940, she and her father were arrested in Birmingham during a protest. The protest was about the arrest of George Harris, a leader of the Farmer's Union. That same year, a newspaper called the Daily Worker published a photo of her. It showed her in a Chicago march, asking for poll taxes to be removed.

She also joined other groups that worked for social change. These included the American Peace Mobilization, the American Youth Congress, and the Southern Negro Youth Congress. She also worked with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), a group of labor unions, and the Southern Conference for Human Welfare. This group worked for social and political changes in the South. Margie left Radcliffe that year because she lost her scholarship. She believed this happened because of her activism.

Activism and Career (1941–1972)

In 1941, Margie married Laurent Brown Frantz. He was also an activist and a member of the Communist Party. That year, she worked at a government printing office in Birmingham. She also worked for the Southern Conference for Human Welfare. In December, she moved to Washington, D.C. There, she worked for a government agency that helped get supplies for the war effort.

Her husband joined the United States Navy. In May 1942, Frantz started working for the Soviet Purchasing Commission. This group helped send American equipment to the USSR for the war. In 1943, she worked for a union called the Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers Union in Birmingham. In 1944, she began working full-time at the Southern Conference for Human Welfare in Nashville.

From 1944 to 1946, Frantz was a secretary for James Dombrowski, a leader of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare. She also edited the Southern Patriot, the group's newspaper. By 1947, she, Dombrowski, and her father were being investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee. This committee looked into people they thought were disloyal to the United States.

In 1950, the Frantzes left Nashville after being targeted by the Ku Klux Klan. They moved to Berkeley, California. They became part of the local activist community in the San Francisco Bay Area. They raised their four children there: Joe, Larry, Virginia, and Alex. In the 1950s, Frantz led the Independent Progressive Party in Alameda County. She supported the Highlander Training and Education Center. She also joined the Northern California Committee against Nuclear Testing. She asked for mercy for convicted spies, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. She also wanted to get rid of the Smith Act, a law that allowed for the registration and deportation of people seen as a threat to the U.S.

In 1955, Frantz met Eleanor Engstrand, who would become her life partner. They connected over their shared interest in politics, social issues, and nature. Engstrand was a librarian at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1956, Frantz left the Communist Party. In 1957, she became an executive secretary at UC Berkeley. She continued in this role even when her boss got a new position. The California State Senate's Un-American Activities Committee questioned her appointment. But her boss said her past activities were not important because of her good work at the university.

In 1961, Frantz and Engstrand fell in love. Their lives and families became connected. Engstrand's husband died in 1967. In 1969, Frantz quit her job after university police used violence against student protesters at People's Park. She decided to go back to school. She formally enrolled at UC Berkeley in 1970. She earned her bachelor's degree with honors in 1972 and started working on her PhD. Around that time, she moved to Ben Lomond, California, with Engstrand.

Return to School and Later Career (1973–1999)

Frantz and Engstrand moved because two of her professors moved to the University of California, Santa Cruz in 1973. Frantz decided to follow them to finish her graduate studies. She started working as a teaching assistant at UC Santa Cruz in 1973. She became a strong supporter of women's rights. Engstrand worked for the Santa Cruz Library Board. Both women became active in the local Quaker community.

Frantz was one of the people who helped start the Women's Studies Department at UC Santa Cruz. In 1976, she became a lecturer in American and Women's Studies. She taught classes on women's history, social movements in the United States, and McCarthyism. For many years, Frantz was on the Women's Studies Executive Committee. She was also a member of the Board of Directors for the Women's Center. She helped and guided LGBT students. Her relationship with Engstrand made them role models for the community.

In 1984, Frantz finished her PhD. She continued her activism throughout the 1980s and 1990s. She spoke at events for groups like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). She warned about the dangers of going back to McCarthyism, a time when people were unfairly accused of being disloyal. She also protested nuclear testing and changes to affirmative action laws. These laws help make sure everyone has equal opportunities.

She gave talks across the country and wrote articles for magazines and newspapers. She officially retired in 1989 and won the Teacher of the Year Award. But she loved teaching too much to stop. She continued lecturing for another ten years. In 1997, she received a Distinguished Teaching Award from the Alumni Association.

Death and Legacy

In her last years, Frantz was not well. Engstrand cared for her until she could no longer do so. Frantz died on October 16, 2015, in Santa Cruz. Her life story was featured in the 1983 documentary film Seeing Red. An interview with Frantz from 2005 is part of a special collection at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts.

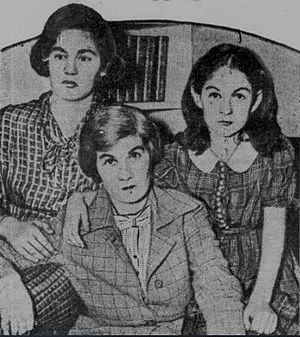

Images for kids