McClintock Arctic expedition facts for kids

Melville Island, Canada

|

|

| Date | 1857 |

|---|---|

| Location | The Arctic |

| Participants | Francis Leopold McClintock and team |

| Outcome | Returned with the only written message recovered from the Franklin expedition |

The McClintock Arctic expedition of 1857 was a British journey to find out what happened to Franklin's lost expedition. That earlier expedition had disappeared in the Arctic. Led by Francis Leopold McClintock, this new trip used a steam yacht called the Fox. The team spent two years exploring the icy region. They eventually found the only written message ever recovered from Franklin's lost ships. For their amazing efforts, McClintock and his crew received the Arctic Medal.

Contents

Why Was This Expedition Needed?

After John Rae reported finding items and hearing stories from the Inuit people, it seemed Franklin's last crew members died near the Back's Great Fish River around 1850. Lady Jane Franklin, Sir John Franklin's wife, really wanted to find out what happened. She also hoped to prove that Franklin had discovered the Northwest Passage. This was a sea route through the Arctic connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

McClintock was chosen to lead this search. He had already explored the Arctic many times. This was the fifth expedition Lady Franklin paid for herself. The British government had given up hope of finding Franklin's crew. Lady Franklin bought the ship Fox in April 1857. It was a 177-ton steam yacht.

Setting Sail for the Arctic

The Fox left Aberdeen, Scotland, on July 1, 1857. It had a skilled crew of 25 people. The ship was specially prepared for the Arctic's harsh conditions. It even had extra wood on its outside to protect it from ice. An Inuit interpreter named Carl Peterson joined the crew. He had worked with other explorers before.

The crew quickly loaded supplies, including lemon juice to prevent scurvy. Scurvy is a serious illness caused by not getting enough Vitamin C. The government also gave them extra equipment and weapons.

The ship stopped briefly at several ports in Greenland. They sent a sick crewman home. They also got coal, more dogs, and more supplies. Two Inuit guides, Anton Christian and Samuel Emanuel, joined them. They left Greenland in early August. Soon, they saw huge icebergs near Disco Bay. By August 12, they reached Melville Bay.

First Winter in the Ice

Within a few days, the ice began to close in on the Fox. The ship could only move a little bit at a time. The crew hunted seals, which helped feed their sled dogs. They slowly drifted west with the huge sheets of floating ice, called the pack ice. By mid-September, they knew they were stuck. On September 18, they started getting the ship ready for winter.

Hunting for birds, seals, narwhal, and polar bears kept the crew busy. The ship's doctor, Dr. Walker, even taught lessons to the crew. In November, they had a successful bear hunt. The bear's skin was saved to be given to Lady Franklin. Soon, the long, dark Arctic winter settled in.

December began sadly with the death of a crewman, Robert Scott. He died from injuries after falling down a hatchway. He was buried at sea on December 4. Temperatures were often colder than -20°F (-29°C). The crew practiced building snow huts, which are like igloos. As February 1858 arrived, the daylight slowly returned, making everyone feel better. By mid-March, open areas of water appeared in the ice. The crew tried many times to free the ship. But the Fox stayed stuck in the ice until April 26. They had been trapped for 242 days!

Arctic Summer Adventures

Two days later, the ship was safely anchored in Holsteinborg, Greenland. The crew rested and got their health and spirits back. They also restocked their food. They left on May 10. For a while, they stayed near Upernavik. They couldn't move forward because of the remaining floating ice. By July, the ice began to break up, and they could make better progress. They added to their food supplies by regularly hunting polar bears, seals, reindeer, and various birds.

Throughout the summer, they met and traded with Inuit people. These Inuit were used to meeting European explorers. However, the crew didn't get any new information about Franklin's expedition. The Inuit did remember other explorers, like John Rae.

By August, the Fox was heading towards Beechey Island. This island was known as Franklin's first winter camp in 1845–1846. They arrived on August 11. The place, which used to be empty, now had a supply house and several small boats. They took letters that had been left there by other search parties. On Beechey Island, McClintock placed a stone monument for Franklin and his crew. Lady Franklin had provided it, and Henry Grinnell had built it. They left Beechey Island on August 16.

The Fox sailed through Barrow Strait. These were the same waters where other ships had been stuck nine years earlier. The crew then explored Bellot Strait. They were already preparing for the next winter. They left supplies on shore for smaller exploration trips in the spring. By September 28, they reached their next wintering spot near Point Kennedy. The ship was prepared for winter again. They also built a special observatory to study Earth's magnetic field.

Second Winter in the Ice

By November, the crew had settled into their winter routine again. They hunted sometimes and even brewed their own sugar beer. Dog sled teams went out to explore and set up supply depots. They faced drifting ice and temperatures of -15°F (-26°C). On November 7, the ship's engineer, George Brands, died suddenly. He was buried on shore. Temperatures dropped to -47°F (-44°C). Animals became scarce, and the winds were very strong.

There was no regular schooling this winter. But some crew members kept busy by studying how to navigate. They celebrated the new year with special parties below deck. By February, animals started to return as the sunlight increased. One crew member got scurvy because he didn't eat the preserved meats.

Amazing Discoveries

Finding Clues About Franklin

On February 17, the sled dogs were split into three teams. McClintock, Young, and Walker led these teams to search further. The temperatures were still very cold. McClintock's dogs struggled a lot, so his trip was shorter than planned. They slept in snow huts at night.

On March 1, they were surprised to meet four Inuit people returning from a seal hunt. One Inuit wore a naval button. He said it came from a group of Europeans who had starved near a river. This matched what John Rae had reported in 1854 about Franklin's last survivors. Another Inuit had met Rae's expedition in the same area.

Two days later, all 45 members of this Inuit group arrived. McClintock bought all the items they had from Franklin's expedition. These were mostly silverware and buttons. None of the Inuit had seen Franklin's crew alive. But several had seen their remains. Some told stories of survivors from a three-masted ship that was crushed by ice west of King William Island. This was the same area Rae had described. McClintock's team returned to the Fox on March 14 with this important evidence. They had traveled about 360 miles (579 km) and mapped 120 miles (193 km) of new coastline. Young's team had already returned to the ship without finding anything major. Walker's team, sent to get hidden supplies, returned without success on March 25.

On April 2, McClintock finally set out for King William Island. He wanted to follow up on the Inuit reports. He planned to split his group into two teams. Lieutenant Hobson would explore the north coast of King William Island. McClintock himself would explore the southern shore.

On April 20, McClintock met another group of Inuit. They gave him many more items from Franklin's expedition. They also described two ships near King William Island. One ship had sunk in deep water. The other was broken on the ice with one body inside. They said the European survivors tried to reach a "large river" with boats that autumn. Many died along the way. The next winter, their bones were found. Following their directions, a skeleton was found on the route on May 24. It was confirmed to be a crewman by his clothes. He seemed to have died right where he fell.

The Final Message

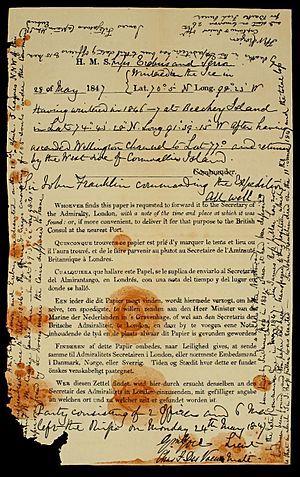

Meanwhile, near Cape Jane Franklin, Lieutenant Hobson's sled party found the first written message from Franklin's Expedition. It was inside a message cairn (a pile of stones). The note had two parts.

The first part, written on May 28, 1847, said:

- H. M. ships 'Erebus' and 'Terror' wintered in the ice in

28 of May, 1847 lat. 70° 05' N. long. 98° 23' W.

Having wintered in 1846–7 at Beechey Island in lat. 74° 43' 28" N.; long. 91° 39' 15" W., after having ascended Wellington Channel to lat. 77° and returned by the west side of Cornwallis Island.

Sir John Franklin commanding the expedition.

All well.

Party consisting of 2 officers and 6 men left the ships on Monday, 24 May 1847.

- Gm. Gore, Lieut.

- Chas. F. Des Voeus, Mate.

Handwritten around the edge of this message was a very important update:

25th April 1848

HMShips Terror and Erebus were deserted on the 22nd April 5 leagues NNW of this having been beset since 12th Sept 1846.

The officers and crews consisting of 105 souls under the command of Captain F. R. M. Crozier landed here — in Lat. 69°37’42’’ Long. 98°41’

This paper was found by Lt. Irving under the cairn supposed to have been built by Sir James Ross in 1831 — 4 miles to the Northward — where it had been deposited by the late Commander Gore in May June 1847.

Sir James Ross’ pillar has not however been found and the paper has been transferred to this position which is that in which Sir J. Ross’ pillar was erected.

Sir John Franklin died on the 11th of June 1847 and the total loss by deaths in the Expedition has been to this date 9 officers and 15 men.

[signed] F. R. M. Crozier Captain & Senior Offr

And start on tomorrow 26th for Backs Fish River

[signed] James Fitzjames Captain HMS Erebus

This second part, signed by Captains Crozier and Fitzjames, said that the ships Terror and Erebus were abandoned on April 22, 1848. They had been stuck in the ice since September 12, 1846. It also stated that Sir John Franklin had died on June 11, 1847. By that date, 9 officers and 15 men had died. The remaining 105 people were planning to leave the next day, April 26, for Back's Fish River. At this point, Franklin's crews were likely trying to save their lives.

McClintock, a few days behind Hobson, kept searching the area. He found a large boat that had been prepared for river travel. It was attached to a big sled. The boat held the skeletons of two men. It also had many objects that would not have been useful for an Arctic journey.

In June, Hobson explored Back Bay. He found another cairn with a second note left by Lieutenant Gore in May 1847. Its message was similar to the first. More abandoned equipment was around this cairn. These sites seemed untouched by the local people. No parts of a ship were seen.

McClintock reached the Fox on June 19, as the ice was melting. Hobson had arrived five days earlier. He couldn't walk because of his difficult journey, but he recovered on the ship. Young had also returned earlier, also tired from the harsh conditions. But he had set out again. A few crew members had signs of scurvy. Thomas Blackwell, the first man to get the disease, had died from it before McClintock returned. Young came back again on June 27. He had mapped Peel Sound but found no new traces of Franklin.

In July, they prepared to leave. They built a cairn with detailed records of their expedition. On August 9, the ice allowed them to start steaming out. Despite losing two engineers and facing dangerous ice, they soon reached open seas. They arrived at the port of Godhavn on the west coast of Greenland on July 29. There, their Inuit guides were paid and left the ship. The Fox arrived in London on September 21, 1859. The expedition had lost three crew members in total.

What Was Learned?

McClintock and Hobson found the last written messages from Franklin's expedition survivors. This confirmed parts of the stories told by the local Inuit. It also confirmed the date of Franklin's death. McClintock also created the first map of the west coast of King William Island. For his important work, he was knighted and became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1865. McClintock and his crew members also received the Arctic Medal.

McClintock saw that the ice in Victoria Strait was always thick. This showed that Franklin's attempt to go south through that passage was hopeless. There was another channel east of King William Island, through James Ross Strait and Rae Strait. This route was protected from the thick ice by the island. Franklin didn't know about it. Roald Amundsen later used these straits to complete the first full journey through the Northwest Passage in 1903–1906.

On January 30, 1920, a newspaper called The Pioche Record reported something interesting. Explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson found a hidden supply cache from an 1853 McClintock expedition on Melville Island. The clothes and food from this cache were in excellent condition. This was amazing, considering the harsh Arctic weather.

Images for kids