Meridian race riot of 1871 facts for kids

The Meridian race riot of 1871 was a violent event that happened in Meridian, Mississippi, in March 1871. It began after the arrest of freedmen (formerly enslaved people) who were accused of causing a downtown fire. Black citizens had also started organizing to protect themselves.

Even though the local Ku Klux Klan (KKK) had attacked freedmen many times without punishment, the first person arrested under a new law meant to stop the Klan was a freedman. This made the black community very angry. During the trial of black leaders, the judge was shot in the courtroom, and a gunfight started, killing several people. After this, angry mobs of white people killed as many as 30 black people over the next few days. White Democrats forced the Republican mayor out of office. No one was ever charged or tried for the deaths of the freedmen.

The Meridian riot was part of a bigger wave of violence after the Civil War. White people wanted to remove Republicans from power and bring back white supremacy. While new laws helped control the Klan for a while, the Meridian riot was a turning point in Mississippi. By 1875, other white groups like the Red Shirts used threats to stop black people from voting. This helped the Democratic Party win state elections. Two years later, the federal government removed its soldiers from the South in 1877.

Quick facts for kids Meridian race riot of 1871 |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Reconstruction Era | |

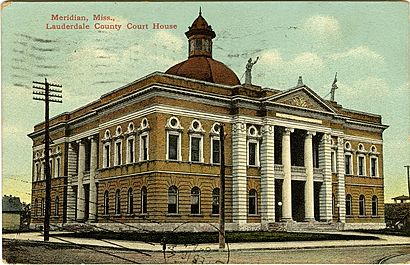

A postcard of the Lauderdale County Courthouse, where Moore arranged a meeting encouraging freedmen in self-defense

|

|

| Date | March 1871 |

| Location | |

| Caused by | Racial polarizing trial |

| Methods | Shootings, Lynchings |

| Resulted in | Various killings |

Contents

Background of the Conflict

The Ku Klux Klan's Role

After the American Civil War ended in 1865, the United States entered a time called Reconstruction. During this period, the United States Army took control of the states that had been part of the Confederacy. White Democrats in the South did not like this. Many of them had lost their right to vote because they fought for the Confederacy.

Their anger grew when new laws made freedmen full citizens and allowed them to vote, serve on juries, and hold government jobs. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) started as different groups after the war. They used public violence to scare black people. They burned homes, attacked, and killed black people, leaving their bodies on roads.

Meridian, the main town in Lauderdale County, had a Republican mayor named Sturgis. He was from Connecticut, so people who didn't like him called him a "carpetbagger" (someone from the North who moved South after the war). Southern Republicans were called "scalawags".

The KKK tried to scare a black school teacher named Daniel Price. Price had moved from Alabama and was a leader in an organization that helped former slaves. Because of threats, Price moved to Meridian, hoping to find work. Many other African Americans were also moving from Alabama to Mississippi. To try and force freedmen to return, a deputy sheriff from Alabama, Adam Kennard, came to Meridian with some KKK members to arrest the men who came with Price.

City officials in Meridian, who were Republicans, refused to help Kennard. They believed he was acting outside his legal area. Freedmen were angry about the Klan's presence. One night, Price and a group of freedmen, dressed in disguises, took Kennard outside the city and beat him. Kennard pressed charges against Price. Price was charged under a law meant to stop the KKK's violence. This law made it a federal crime to commit violence while in disguise.

The start of the riots was linked to the KKK's constant attacks. These attacks forced freedmen to leave farms in Sumter County, Alabama, and seek safety in Meridian, which was about 40 miles away. Some reports say that Adam Kennard was actually a black former slave who was deputized by farmers and sent with KKK members to bring back farm workers. Daniel Price was a white Republican teacher at an all-black school.

Daniel Price's Trial

In the week before Price's trial, white people in Meridian began to threaten him. Freedmen were very upset that Price was arrested, especially since no one had been arrested for the many attacks on black people. Price was the first person arrested under what was seen as the federal anti-KKK law. Black people were angry that a law meant to protect them was being used against them.

Before his trial, Price said he would not pay bail and would not go to jail. He claimed his supporters "would begin shooting" if he was found guilty. When about 50 armed white men came from Alabama to watch the trial, city officials became worried. They delayed the trial for a week. During this time, the Alabamians arrested several freedmen who had moved with Price, claiming they had broken work contracts or stolen money.

When Price's trial was set for the second time, a witness for Kennard was sick, so the court delayed it again. During this time, several important city workers told Mayor Sturgis they were worried about mass unrest if Price was tried. They suggested avoiding the trial and instead making Price leave the city. Sturgis and other officials made a deal: Price was freed on the condition that he leave Meridian.

Because Price was not there for his third trial date, the prosecutor dropped the charges against him. However, the black community in Meridian was still very angry. They learned that Kennard had arrested several Alabama freedmen and forced them back to Livingston. The white community organized against Mayor Sturgis and asked for him to be removed from office. Black citizens responded with their own request to the Republican governor, Adelbert Ames, who had appointed Sturgis. Sturgis was not removed, but he became more and more worried about the growing hostility between the races.

Courthouse Meeting and Downtown Fire

Soon after Price's trial and departure, the 1870 governor's election took place. The Republican James L. Alcorn won, largely because freedmen in Lauderdale County voted for him. Because of the unrest in Meridian, Mayor Sturgis asked for federal soldiers. No local officials wanted to charge the Alabamians or other white people in the city. The soldiers arrived but only stayed a few days. Since there was no major violence, they left because the state had limited resources.

Sturgis started his own legal actions against some white people in the city. This led to more opposition and renewed efforts to remove him. Sturgis sent several black advisors to the governor's office in Jackson to explain his situation.

When Sturgis's advisors returned to Meridian on Friday, March 3, 1871, they brought Aaron Moore. Moore was a Republican member of the Mississippi Legislature from Lauderdale County. He called for a meeting the next day, March 4, at the county courthouse. The goal was to argue for keeping Sturgis in office. About 200 people came to the meeting, but only a few were white. Speeches reportedly criticized violent white people and encouraged freedmen to defend themselves. The meeting ended at sunset. Afterward, several black people from the meeting formed a small military group, led by William Clopton, one of Sturgis's advisors. Some had swords, others had guns. Many freedmen avoided this demonstration.

Even before the courthouse meeting, trouble was building. White people spread rumors about seeing groups of armed African Americans coming into the city, which increased their fears. A local store owner heard a conversation predicting that many people, both black and white, would be on the streets that night. When white people heard about the courthouse meeting, they decided that Sturgis, Clopton, and Warren Tyler (another of Sturgis's advisors) should be forced to leave the city. They formed an armed group to find them.

About an hour after the meeting ended, a fire started in the business area of the city. The fire began on the second floor of a store owned by Theodore Sturgis, the mayor's brother. No one knows for sure what caused the fire, but many people at the time thought the mayor was behind it. The fire was eventually put out, but not before two-thirds of the business district was burned. This area had just been rebuilt after being destroyed during General William Tecumseh Sherman's raid in 1864.

As the fire burned, Clopton was hit in the head with a shotgun. Some thought he was killed, but he was only wounded. When freedmen heard about the attack, they became very angry and started handing out guns. At the same time, groups of white people patrolled the streets like militias for the rest of the night. For the next few days, under mob rule, the sheriff arrested Clopton, Tyler, and Moore, charging them with causing a riot. White people formed a committee to remove Mayor Sturgis from office.

Rumors spread quickly. White people said black people would burn the whole city down. The sheriff told Moore at his church on Sunday that all black people in the city would have to give up their weapons. On Monday, the committee started investigating the fire and decided that Mayor Sturgis had set it.

The Riot Erupts

After being arrested, Clopton, Tyler, and Moore were brought to trial on Monday, March 6. That morning, white people held their own meeting. They passed a resolution condemning the violent actions of Daniel Price, Mayor Sturgis, and others on the night of the downtown fire. When William Tyler was arrested, Sheriff Moseley checked him for weapons and found none. He then allowed Tyler to go to the barbershop for a haircut. The barber, Jack Williams, later claimed he saw Tyler wearing a pistol. Tyler went to the courtroom after leaving the barbershop.

Judge E. L. Bramlette was in charge of the trial. Many Republicans and as many as two hundred Democrats were in the courtroom. Generally, the white people sat toward the front, and the black people were in the back. Before witnesses were questioned, Mayor Sturgis was seen talking with Tyler and gave him a note. After the trial began, Tyler and Moore were taken into another room. Some reports say Sturgis went with them. Sturgis never returned to the courtroom. When Tyler and Moore came back, several witnesses reported that Tyler had a pistol that they had not seen before.

The second witness to speak was James Brantley. Tyler asked Brantley to stay on the stand and reportedly said, "I want to introduce two or three witnesses to question your honesty." Brantley became very angry. He grabbed a cane from Marshal William S. Patton and moved toward Tyler. Patton grabbed Brantley and told him to stop. Tyler moved toward the courtroom door. Some witnesses claimed to have seen Tyler reach for a gun. At this moment, the first shot was fired, but who fired it is debated. Marshal Patton said he did not see Tyler shoot, but he thought the shot came from that direction. When the first shot was fired, Tyler was not in much danger, as he was 10 to 12 feet from Brantley. Several people in the courtroom claimed that Tyler fired first.

Guns were quickly pulled across the courtroom, and a general shooting started. The shootout lasted between one and five minutes. During this time, Judge Bramlette was killed, and Clopton was injured. Tyler ran to a second-floor veranda, jumped over the railing, and landed on the ground. The barber Jack Williams reported seeing him throw away what looked like a pistol as he jumped. Tyler limped toward Williams asking for help, then ran through the barber shop with several white people chasing him. Dr. L. D. Belk, a deputy sheriff, chased Tyler and asked men to get weapons and help. Tyler was found wounded in a ditch by a black worker named Joe Sharp. Sharp and two other men helped Tyler get to a store. A group of white people later found Tyler and shot him many times. There were so many people in the crowd that no one knew who had hit him.

After the courtroom shootout, Clopton was badly injured and placed under guard. Reportedly, the two guards grew tired and threw Clopton from the second-story window, saying they "could not waste their time on a wounded Negro murderer." Clopton was carried back into the courthouse, where he died sometime during the night after his throat was cut.

Moore had fallen near Judge Bramlette and pretended to be dead. After the courthouse was cleared, he ran to the woods to follow the railroad line to Jackson. A mob chased him for 40 or 50 miles, but they never caught him. He eventually reached Jackson safely and was never arrested or tried again. The white mob burned down Moore's house along with a nearby Baptist church. The church had been given by the U.S. government to be a school for black children, and Daniel Price had been a teacher there.

In the chaos after the courtroom shooting, white people killed many other black people. When they could not find Tyler and Moore, they attacked other freedmen they came across. For three days, local Klansmen murdered "all the leading colored men of the town with one or two exceptions." Several black people were killed in the courtroom. Others died in the fires at Moore's house and the Baptist church. On the night of the shootings, three other black people were arrested and taken to the courthouse. The next morning, they were found dead. By the time federal soldiers arrived several days later, about thirty black people had been killed. Many of those who died in the riot were buried in McLemore Cemetery.

Aftermath and Impact

During the riot, Mayor Sturgis hid in the attic of a boarding house owned by his brother. He did not come out until he agreed to resign and leave town. The day after the riot, men approached him and ordered him to return to the North. He agreed to leave that night on a northbound train at midnight. A group of about 300 white men safely escorted him to the train. When he reached New York City, he wrote about the events in a letter to the New York Daily Tribune:

They were all armed with double-barreled shot guns, and, as I was told, 200 in number, Many good citizens of Meridian plead for me, as well as many in the Ku-Klux columns who were in them not from choice, but from necessity. They appointed committee after committee to wait upon me and to inform me that I must leave by 10 o'clock the next day. Their principle commanders visited me. I wanted to know the whys and wherefores, but they said they came not to argue any question of right – the verdict had been rendered. They treated me respectfully, but said that their ultimatum was that I must take a Northern-bound train. I yielded. At about 12 o'clock at night, perhaps 300 came and escorted me to the cars. Some difficulties and dangers presented themselves, but I got here in safety.

[...]

I am much a sufferer in pain and feeling, but I believe that the State of Mississippi is able to indemnify me. Let me urge the necessity of having martial law proclaimed through every Southern State. The soldiery to be sent there should be quartered on the Rebels. Leniency will not do. Gratitude, they have none. Reciprocation of favors they never dream of.

This letter was printed widely in the North. It helped fuel the debate about making the Ku Klux Klan Law stronger. News of the riot angered the Radical Republicans in Congress and sped up the passage of the new law, known as the Enforcement Act. Mississippi Democrats criticized the Radical Republicans for using the riot for political gain.

The situation in Meridian slowly became calmer, but discussions continued there and in Washington. On March 21, the state started an investigation into the riot, calling 116 witnesses. The state charged six men with unlawful assembly and trying to kill someone. Many black witnesses had important information about who shot whom, but most were too afraid to testify. They feared losing their jobs, rights, or even their lives. None of the men responsible for the riot were charged or brought to trial. Two months later, a Congressional investigation looked at the case again but could not identify who fired the first shot in the courtroom. The only person found guilty of actions related to the riot was an Alabama KKK member charged with attacking a black woman.

Long-Term Effects

The Meridian riot showed that black people in the South were not well-armed. They depended on white people for jobs and were new to freedom. They found it hard to resist violent attacks without help from the federal government. By the mid-1870s, as memories of the war faded, white people in the North grew tired of paying for expensive programs to stop violence in the South. They were more willing to let the states handle their own problems. Most Northerners saw slavery as wrong but did not necessarily believe in racial equality. They were discouraged by the ongoing violence in much of the South. White people used force to stop opposition. With less federal help, black people found it hard to resist white violence. The riot marked the decline of Republican power and the weakening of Reconstruction in this part of Mississippi.

By 1875 in Mississippi, new insurgent groups like the Red Shirts and rifle leagues had replaced the Klan. These groups were described as "the military arm of the Democratic Party." They openly worked to scare Republican voters, especially freedmen, and force officials out of office. These groups stopped people from voting, which led to huge victories for the Democratic Party in the 1875 state elections. By the late 1870s, Democrats had taken full control in Mississippi and other former Confederate states.

With control back at the state government level, conservative Democrats passed laws and changes to the state constitution. These laws aimed to stop freedmen and poor white people from voting. This led to their disfranchisement (loss of voting rights) for decades. Mississippi was the first state to pass such a change in 1890. When the U.S. Supreme Court allowed it, other Southern states passed similar changes, known as the "Mississippi Plan." State governments also passed Jim Crow laws, which created racial segregation in public places. The decades after the Meridian Riot saw a rise in lynchings and violence against black people across the South. This went along with their loss of civil rights and the fight for white supremacy. Mississippi would lead the region in racial violence and public support for it. While the number of lynchings decreased in the 20th century, black people had little legal help against abuses until their successes in the Civil Rights Movement and the enforcement of their right to vote.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |