Milky stork facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Milky stork |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| An individual foraging among bulrush in Singapore | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Ciconiiformes |

| Family: | Ciconiidae |

| Genus: | Mycteria |

| Species: |

M. cinerea

|

| Binomial name | |

| Mycteria cinerea (Raffles, 1822)

|

|

|

|

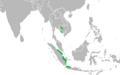

| resident extant range | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The milky stork (Mycteria cinerea) is a special type of stork that mostly lives in mangrove forests in Southeast Asia. You can find it in countries like Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia. This stork is about 91–97 centimeters (about 3 feet) tall. It has a wingspan of 43.5–50 centimeters and a tail that's about 14.5–17 centimeters long. Its feathers are mostly white, except for some black feathers on its wings and tail.

Sadly, since the 1980s, the number of milky storks in the world has dropped a lot. There used to be about 5,000, but now there are only around 2,000. This is mainly because their homes are being destroyed, too many fish are being caught (which means less food for them), and baby storks are illegally taken and sold. Because of these problems, the milky stork is now listed as an Endangered animal on the IUCN Red List.

Contents

About the Milky Stork

What it Looks Like

The milky stork is a medium-sized bird, standing about 91–97 centimeters tall. It's a bit smaller than its close relative, the painted stork. Adult milky storks are almost completely white. The only exceptions are their black flight feathers on the wings and tail, which have a cool greenish shine. During the time they breed, their white feathers get a pale, creamy yellow color, which is why they are called "milky."

The skin on their face is usually greyish or dark red, with black spots. When they are breeding, this skin turns a deep wine red, with brighter red skin around their eyes. After breeding, the facial skin fades to a lighter orange-red.

Their long, curved beak is a dull pinkish-yellow, sometimes with a white tip. Their legs are a dull reddish color. They have long, thick toes that help them walk on soft mud without sinking too much when they are looking for food.

When storks are trying to find a mate, their beak turns a deep yellow, and their legs become a bright magenta color. Male and female milky storks look very similar, but males are usually a bit bigger with a longer, thinner beak.

You can easily spot an adult milky stork by its white head feathers, yellow-orange beak, and pink legs. It looks different from other wading birds like egrets because of its mostly white body and black wing feathers. However, it can sometimes be confused with the Asian Openbill or white egrets. Egrets are smaller and completely white. The Asian Openbill is also smaller and has a grey beak. In some areas, milky storks live near painted storks. You can tell them apart because painted storks have black and white patterns on their chest and wings, pink inner wing feathers, and brighter colors on their bare skin.

Like other storks, milky storks often fly by soaring high in the sky on warm air currents called thermals. You might see groups of up to a dozen storks soaring together between 10 AM and 2 PM. When one stork takes off from a breeding colony or feeding spot, others often follow quickly.

Baby Storks and Young Birds

When milky stork chicks hatch, they are covered in soft white down. After about 10–14 days, their main feathers start to grow, and they are fully feathered in 4–6 weeks. Young storks are usually pale greyish-brown with a white lower back and tail feathers. They have dark wing and tail feathers, and their head is covered in greyish-brown feathers. Their bare skin parts are a dull yellow.

Around 10 weeks old, when they start to fly, they begin to lose their head feathers. Dark, bare patches appear on their forehead and around their eyes, sometimes with dull orange spots. Baby storks also have a dark brownish-grey beak and skin around their beak and eyes.

By three months old, their head is completely bald, and their dull beak turns a warm yellow with a greenish tip, just like adult storks. Young milky storks look very similar to young painted storks. However, milky stork juveniles have paler feathers under their wings that stand out against their black flight feathers, while painted stork juveniles have completely black underwing feathers.

Sounds They Make

Milky storks are usually quiet when they are not breeding. At their nests, adults make a high-pitched "fizz" sound during certain displays. Young storks make a croaking sound, like a frog, when they are begging for food.

Hybrids

Sometimes, in zoos like the National Zoo of Malaysia or Singapore Zoo, milky storks and painted storks have babies together. These babies are called hybrids, and they can look like a mix of both parents. It can be hard to tell hybrid babies apart from purebred ones just by looking at them. Adult hybrids might have a pink beak and head (instead of orange like a painted stork) and sometimes small black spots or a pink tint on their white wing feathers.

All milky storks, no matter their age, have dark brown eyes. Their legs are pinkish, but they often look white because of the birds' droppings covering them.

Where Milky Storks Live

Milky storks live only in Southeast Asia. You can find them in places like Sumatra (where most of them live), Java, Sulawesi, eastern Malaysia, Cambodia, southern Vietnam, Bali, Sumbawa, Lombok, and Buton. They used to live in southern Thailand, but they are probably gone from there now. Sometimes, a milky stork might visit Thailand or other places like Bali and Sumbawa, but they don't live there all the time.

The milky stork used to live in more places across Southeast Asia. For example, they were once common along the coasts of the Malaysian Peninsula, but now they are mostly found in the Matang Mangrove Forest in Perak.

Milky storks mostly live in lowland coastal areas. They prefer mangrove forests, freshwater and peat swamps, and river mouths. They also look for food in mudflats when the tide is out, in shallow salty or fresh water pools, marshes, fishponds, and even rice fields. They can go up to 15 kilometers away from the coast to find food.

For breeding, milky storks need large, untouched mangrove forests with tall trees behind them. These tall trees are important for resting and for taking off when they fly. They also need shallow pools within the forest where their young can find food. If there aren't enough suitable trees, people have suggested using man-made structures like cart wheels on poles for them to nest on.

How They Move Around

Milky storks probably travel short distances outside of the breeding season, but we don't know much about when or where they go. Sometimes, they might move locally because of droughts during the dry season. In Cambodia, they spread out from Tonlé Sap Lake during the wet season, likely heading towards the coast. Milky storks have been seen migrating from Sumatra to Java, and across the Sunda Straits, in September and October. They can fly over 200 kilometers in a single day!

Adult storks that breed on the Javan island of Pulau Rambut fly back and forth every day to feed at fishponds and rice fields on the mainland of Java.

Milky Stork Life and Habits

Reproduction and Breeding

Milky storks usually start breeding after the rainy season, during the dry season, which can last from April to November. The exact timing can change depending on the area, but breeding usually lasts for three months. This time probably matches when there are the most fish available after they reproduce in the rainy season. For example, in South Sumatra, milky storks breed from June to September.

Milky storks build their nests together in groups called colonies, usually in mangrove swamps. These colonies can have anywhere from 10–20 nests to several hundred. In Java, some colonies have 75–100 nests covering a large area, with 5–8 nests in a single tree! Nests are often built in tall Avicennia marina trees or Rhizosphora apiculata trees, usually 6–14 meters above the ground, but sometimes even higher, at the very tops of trees. Some storks in Indonesia even nest closer to the ground in dense shrubs. They also commonly nest in dead or dying mangrove trees.

Their nests are strong and bulky, about 50 centimeters wide. They are mostly made of fresh sticks from Avicennia trees, often with leaves still attached. Storks break off live branches by grabbing them with their beak and flying up a short distance. This looks difficult, and they don't always succeed! They keep building their nests even after the young have hatched.

A milky stork usually lays 1–4 eggs, but 2–3 eggs are most common. The eggs are relatively small compared to the adult bird. The eggs hatch after about 27–30 days. Sometimes, there can be several days between the first and last egg hatching, so the chicks can be very different in size. Both the male and female stork take turns sitting on the eggs to keep them warm. When one parent returns to the nest, they greet each other with loud, fast bill-clattering, bowing their heads, and stretching their necks.

During courtship, both partners bow and raise their bills repeatedly, standing opposite each other. Many of their displays at the nest are similar to those of other Mycteria storks.

In South Sumatra, milky storks breed alongside other birds like lesser adjutants, black-headed ibis, and various heron species. In Cambodia, they have been seen breeding with painted storks, lesser adjutants, and spot-billed pelicans in flooded forests.

Breeding in Malaysia is rare and often not successful. Although some adult storks were seen in breeding plumage and nests were reported in the past, no young storks have been seen in Malaysia since 1983. This lack of success is probably due to many predators. Breeding no longer happens on the Javan Island of Pulau Dua because it became connected to the mainland, allowing humans to easily access it and cut down trees, removing good nesting spots. However, some breeding still occurs on Pulau Rambut.

In the wild, young storks start to leave their birthplaces when they are 3–4 months old. In zoos, milky storks sometimes breed with painted storks. There was even one hybrid baby born at Jurong Bird Park in Singapore, from a male lesser adjutant and a female milky stork!

What They Eat

Milky storks eat a variety of foods. In Malaysia, they mainly eat mudskippers (a type of fish) that are 10–23 centimeters long. In South Sumatra, catfish might be a main part of their diet. They also eat other fish like milkfish, giant mudskippers, mullet, eel catfish, and pomfret. Snakes and frogs are also sometimes eaten, especially to feed to their young. Parents feed their babies large fish, eels, and mudskippers up to 20 centimeters long.

Milky storks usually find and catch their food by touch, using their beak to feel around. This method works best when there are many fish close together. They walk slowly through shallow water with their beak partly open and submerged. When they feel a fish, they quickly snap their beak shut, lift their head, and swallow the fish whole. After eating a big fish, they might rest for a minute before looking for more food. Sometimes, they stand still at the water's edge with their beak half-open, letting water flow through it. They also sometimes sweep their beak from side to side in the water until they touch something.

Another common way they find food is by poking their beak into deep holes in the mud. With their beak partly open, they push it into and out of the mud for several seconds per hole.

Milky storks also use other ways to find food, similar to other storks. They might stir the riverbed with one foot to scare out hidden aquatic animals. They also often feed in groups when there's a lot of prey. They work together to push fish into shallow water, making them easier to catch. Milky storks often feed alongside other wading birds like lesser adjutants and egrets. Sometimes, they even look for prey by sight.

During and after the local rainy season (November to March), many milky storks look for food in flooded rice fields. Fewer storks are seen at the coast during this time, suggesting that the inland areas offer better feeding conditions. Young storks often look for food near their breeding colony in shallow mangrove pools where there are many fish.

Other Habits

When the tide is high, milky storks often rest in mangrove trees or in trees in rice fields. They also roost in the tops of tall mangrove trees and on the ground in mudflats and marshes. Between looking for food, they might stand in shaded spots or in the sun with their wings slightly drooped.

Milky storks often preen each other, especially breeding partners. They also shake their heads. Birds perched near their partners might rub their heads, oiling their bare head skin from a special gland and then rubbing it on their feathers.

Threats and Survival

The number of milky storks around the world has been dropping a lot, especially since the late 1980s. This is mainly because their homes are being destroyed and disturbed. People are cutting down mangrove forests for things like fish farms, rice fields, timber, and new settlements. When these forests are destroyed, the storks lose the tall trees they need for nesting, which affects their ability to have babies.

Breeding colonies have also shrunk because of the illegal international trade of these birds since the mid-1980s. In South Sumatra, people also poach their eggs and young storks for food. Young storks are often sold to zoos in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Brunei, and some European zoos. Milky storks are generally sensitive to human disturbance, which also helps explain why their numbers have gone down so much. Even though fishponds and shrimp farms can provide extra feeding grounds, these human-made places can disturb nearby breeding areas, which hurts the population in the long run.

The milky stork was almost wiped out in Vietnam because mangrove swamps were destroyed during the Southeast Asian War (1963–75). However, large-scale replanting of trees since then might have helped some storks return. Still, the species has also suffered long-term effects from chemicals used in Southern Vietnam in later years.

Milky storks have several natural predators. In South Sumatra, monitor lizards (like the Varanus salvator) eat milky stork eggs and young. Crocodiles (like the Crocodilus porosus) also sometimes eat young storks. In Malaysia, brahminy kites, water monitor lizards, and common palm civets are potential predators of nests and probably contribute to low survival rates there. In zoos in Malaysia, crab-eating macaques (a type of monkey) could also be a threat to stork eggs and chicks, as these monkeys can swim to nest sites surrounded by water. On Pulau Rambut, potential predators include reticulated pythons, cat snakes, and Brahminy kites. White-bellied sea eagles and monitor lizards also eat chicks there.

Another possible threat to milky storks is pollution in their homes from high levels of metals like copper, zinc, and lead. This pollution comes from things like farm chemicals, rust from jetties and boats, and fish farming. On Pulau Rambut, breeding colonies might also be threatened by increasing sea pollution.

To help the milky stork population recover, a lot of effort has gone into captive breeding programs. In 1987, the first captive breeding and reintroduction project for the milky stork started at Zoo Negara in Malaysia. They started with 10 young storks from Singapore Zoo and Johor Zoo. From these 10 birds, the captive population grew to over 100 by 2005. So, while the wild population in Malaysia decreased, the number of storks in captivity grew steadily.

The first successful reintroduction of milky storks happened in Kuala Selangor Nature Park in 1998, when 10 captive-bred storks were released. The Matang Mangrove Forest in Malaysia has been a popular place for reintroduction because it's a good habitat for milky storks, offering shelter, breeding grounds, and food. It also seems to have few threats from predators or parasites. This area is protected and managed carefully. However, storks released into the wild face new challenges, such as getting sick, not knowing how to hunt for food or defend their territory, and not being good at spotting and avoiding predators. These released birds could also carry diseases or parasites that might harm wild populations.

For storks in captivity, there's a risk of losing their unique genes if they breed with painted storks. This can happen in zoos or in the wild where their ranges overlap.

Successful conservation of this species in the wild has involved creating a network of protected wetland areas. This has been done in Vietnam with reforestation and protection plans, which may have helped the species return. Raising public awareness about the milky stork and its endangered status is also very important for successful conservation.

Milky Storks and Humans

Local people in Indonesia know the milky stork well and can easily tell it apart from other wading birds. Historically, it was often hunted (sometimes illegally) for its meat and eggs. Like many other wading birds, the milky stork is sometimes seen as a minor pest by fish farmers because it eats commercial fish and shrimp. However, this stork is officially protected in Malaysia and Indonesia and has been listed on Appendix I of CITES since 1987, which means it's highly protected from international trade.

This stork has appeared in zoos around the world. The longest-living milky stork in captivity lived for over 12 years at Washington Park Zoo. Many young storks bought by zoos were mistakenly identified as young painted storks but later turned out to be milky storks. Only a few zoos, like Zoo Negara (where they first bred in captivity in 1987), San Diego Zoo, and Singapore Zoo, have successfully bred this species. Captive breeding and reintroduction programs for this stork have received a lot of support from government and non-government groups.

A milky stork in flight is featured on the logo of Sembilang National Park. It has also often appeared on calendars and posters in public awareness campaigns in Sumatra.

Status of the Milky Stork

In 2008, there were fewer than 2,200 milky storks in the world. This is a big drop from about 5,000 in the 1980s. In Malaysia, the population steadily decreased from over 100 storks in 1984 to less than 10 by 2005 (a drop of over 90%). This means the population there is close to disappearing completely.

Of the current world population, about 1,600 storks are probably in Sumatra, less than 500 in Java, and less than 100 on the Southeast Asian mainland. The population in Cambodia is very small, with only 100–150 storks. Although it might be somewhat stable, rapid declines are expected if serious threats continue. Because of these big population drops across its range, the milky stork's status was changed from "Vulnerable" to "Endangered" by the IUCN in 2013.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |