Millicent Fawcett facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Dame

Millicent Fawcett

|

|

|---|---|

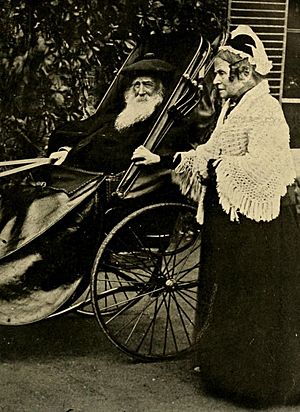

Millicent Fawcett, c. 1873

|

|

| Born |

Millicent Garrett

11 June 1847 |

| Died | 5 August 1929 (aged 82) Bloomsbury, London, England

|

| Monuments | Statue of Millicent Fawcett |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Suffragist, union leader |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Philippa Fawcett |

| Parent(s) | Newson Garrett Louisa Dunnell |

| Relatives | Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (sister) Louisa Garrett Anderson (niece) |

Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett (born Garrett; 11 June 1847 – 5 August 1929) was an important English politician, writer, and a champion for women's rights. She worked hard for women's right to vote by changing laws. From 1897 to 1919, she led Britain's largest group for women's rights, the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). She once said she was always a suffragist, meaning she always believed in women's right to vote.

Millicent also helped women get better education. She was a leader at Bedford College, London and helped start Newnham College, Cambridge in 1875. In 2018, 100 years after the Representation of the People Act 1918 gave some women the right to vote, she became the first woman to have a statue in Parliament Square.

Contents

About Millicent Fawcett

Early Life and Education

Millicent Fawcett was born on 11 June 1847 in Aldeburgh, England. Her father, Newson Garrett, was a businessman. Her mother was Louisa Dunnell. Millicent was the eighth of their ten children.

The Garrett family was close and happy. Children were encouraged to be active, read a lot, and share their ideas. They also talked about politics with their father.

Millicent's older sister, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, became Britain's first female doctor. Elizabeth introduced Millicent to Emily Davies, another important woman who fought for women's rights. Emily Davies told Millicent that she was younger, so she should focus on getting women the right to vote.

In 1858, when Millicent was 12, she went to a private boarding school in London. Her sister Louise took her to hear sermons by Frederick Denison Maurice. His ideas about religion and society influenced her. In 1865, she heard a lecture by John Stuart Mill, a famous thinker. The next year, she helped the Kensington Society by collecting signatures. They asked Parliament to let women who owned homes vote.

Marriage and Family Life

John Stuart Mill introduced Millicent Fawcett to many other people who supported women's rights. One of them was Henry Fawcett, a member of Parliament. Millicent and Henry married on 23 April 1867. Henry had lost his sight in an accident, and Millicent helped him as his secretary.

Their marriage was based on shared ideas and understanding. Millicent wrote books and took care of Henry. They had homes in Cambridge and London. They believed in fair representation and more chances for women. Their only child, Philippa Fawcett, was born in 1868. Millicent strongly encouraged Philippa's studies. In 1890, Philippa became the first woman to get the highest score in the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos exams.

In 1868, Millicent joined the London Suffrage Committee. In 1869, she spoke at the first public meeting in London that supported women's right to vote. She was known for having a clear voice when she spoke. In 1870, she published her book Political Economy for Beginners, which was very popular. She also helped start Newnham Hall in 1875 and worked on its council.

Millicent also helped raise four of her cousins who had lost their parents.

After her husband Henry died in 1884, Millicent took a break from public life. She later moved with Philippa to her sister Agnes Garrett's house. When she returned to work in 1885, she focused on politics. She became a key member of the Women's Local Government Society. She was originally a Liberal but joined the Liberal Unionist party in 1886. She did this because she did not agree with allowing Irish Home Rule.

In 1891, Fawcett wrote an introduction for a new edition of Mary Wollstonecraft's book A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. This essay was important because it brought attention back to Mary Wollstonecraft, an early feminist thinker.

In 1899, the University of St Andrews gave Fawcett an honorary doctorate of law.

Fighting for Women's Rights

Millicent Fawcett started her political work at age 22, at the first meeting for women's right to vote. After another leader, Lydia Becker, died, Fawcett became the head of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). This was Britain's main group working for women's suffrage.

She took a calm approach, staying away from the more aggressive actions of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). She believed that violent protests would hurt women's chances of getting the vote. Even though the WSPU got a lot of attention, the NUWSS, with its slogan "Law-Abiding suffragists," had more support. By 1905, Fawcett's NUWSS had almost 50,000 members.

Millicent explained why she did not support the more militant groups in her book What I Remember. She said she could not support a group that was ruled by just one person and decided to use violence. She believed the NUWSS should stick to using arguments and common sense, not violence or breaking laws.

The Second Boer War gave Fawcett a chance to show women's abilities. She was chosen to lead a group of women sent to South Africa in 1901. Their job was to look into the terrible conditions in camps where families of Boer soldiers were held. No British women had been given such a task during wartime before.

Fawcett supported many other campaigns over the years. For example, she worked to make cruelty to children a crime. She also fought to stop women from being excluded from courtrooms during certain cases. She also worked to end the "white slave trade."

Millicent wrote three books and many articles. Her book Political Economy for Beginners was published ten times and translated into many languages. She also helped found Newnham College for Women in Cambridge. She often spoke at schools and colleges. In 1904, she left the Unionist party because she disagreed with their trade policies.

When the First World War began in 1914, the WSPU stopped its activities to help with the war. Fawcett's NUWSS continued to campaign for the vote during the war. They also supported hospitals and training camps. They showed how much women were helping the war effort. Millicent stayed in her role until 1919, a year after the first women got the right to vote. After that, she focused on writing books, including a biography of Josephine Butler.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1919, the University of Birmingham gave Fawcett an honorary doctorate. In 1925, she was given the title Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE).

Millicent Fawcett died in 1929 at her home in London. She was cremated, but where her ashes are is not known. In 1932, a memorial for Fawcett was placed in Westminster Abbey. It says she was a "wise, constant and courageous Englishwoman" who "won citizenship for women."

Remembering Millicent Fawcett

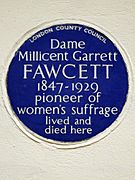

The Millicent Fawcett Hall was built in 1929 in Westminster. It was a place for women to have debates and discussions. Today, it is used by a school for drama. St Felix School, near where Fawcett was born, has named one of its boarding houses after her. In 1954, a blue plaque was put on her home in London where she lived for 45 years.

Millicent Fawcett's writings and papers are kept at The Women's Library in London. In 2018, one of the buildings at the London School of Economics was renamed Fawcett House because of her role in the women's suffrage movement.

In February 2018, a BBC Radio 4 poll named Fawcett the most influential woman of the past 100 years. The Millicent Fawcett Mile is a one-mile running race for women that started in 2018 in London.

Statue in Parliament Square

In 2018, 100 years after the Representation of the People Act 1918 gave some women the right to vote, Millicent Fawcett became the first woman to have a statue in Parliament Square. This happened after a campaign that gathered over 84,000 signatures.

Fawcett's statue holds a banner with a quote from a speech she gave: "Courage calls to courage everywhere." At the statue's unveiling, then-Prime Minister Theresa May said that she and other female politicians would not have their rights if it were not for Dame Millicent Fawcett.

Notable Works

- 1870: Political Economy for Beginners Full text online

- 1872: Essays and Lectures on Social and Political Subjects (with Henry Fawcett) Full text online.

- 1872: Electoral Disabilities of Women: a lecture

- 1874: Tales in Political Economy Full text online

- 1875: Janet Doncaster, a novel, set in her birthplace of Aldeburgh, Suffolk Full text online

- 1889: Some Eminent Women of our Times: short biographical sketches Full text online

- 1895: Life of Her Majesty, Queen Victoria Full text online

- 1901: Life of the Right Hon. Sir William Molesworth Full text online

- 1905: Five Famous French Women Full text online

- 1912: Women's Suffrage : a Short History of a Great Movement ISBN: 0-9542632-4-3 Full text online

- 1920: The Women's Victory and After: Personal reminiscences, 1911–1918 Full text online

- 1924: What I Remember (Pioneers of the Woman's Movement) ISBN: 0-88355-261-2 Full text online

- 1926: Easter in Palestine, 1921-1922 Text online

- 1927: Josephine Butler: her work and principles and their meaning for the twentieth century (written with Ethel M. Turner)

Gallery

- Legacies in London

-

Statue, Parliament Square

-

Blue plaque, Gower Street, Bloomsbury

See also

In Spanish: Millicent Fawcett para niños

In Spanish: Millicent Fawcett para niños