Mississippi Civil Rights Museum facts for kids

|

|

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum in 2017

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Established | 2011 (funding); December 9, 2017 (opening) |

|---|---|

| Location | Jackson, Mississippi |

| Type | Public |

| Visitors | 500,000+ |

The Mississippi Civil Rights Museum is a special place in Jackson, Mississippi, United States. Its main goal is to show and teach everyone about the American Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi. This movement happened between 1945 and 1970.

The museum tells the stories of brave people who fought for equal rights. It helps us understand a very important time in history. The idea for the museum started many years ago. It finally opened its doors on December 9, 2017. The Mississippi Department of Archives and History manages the museum.

It is the first museum about civil rights in the United States that was created and supported by a state government.

Contents

Creating the Museum

Early Ideas

The idea for a civil rights museum in Mississippi began in the 1980s. At that time, the Mississippi State Historical Museum had a small exhibit about civil rights. But people wanted a bigger, dedicated museum.

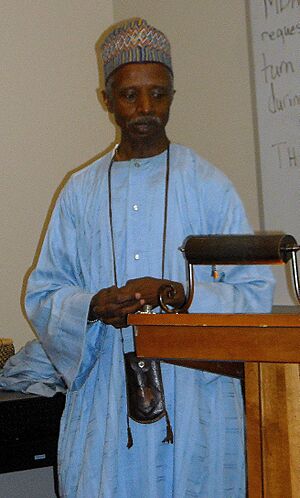

By 2001, activists, historians, and tourism leaders started serious planning. They wanted a place to honor the civil rights movement. Iola Williams, from Hattiesburg, was a key person who pushed for the museum.

Getting Support

Starting in 2000, State Senator John Horhn worked hard to get money for the museum. He introduced bills every year, but they didn't pass at first. Other lawmakers, like Erik R. Fleming, also supported the idea.

In 2006, State Senator Hillman Frazier helped create a study group. This group looked into how to build the museum. They suggested a $50 million museum in Jackson. It would also connect to a "civil rights trail" across the state.

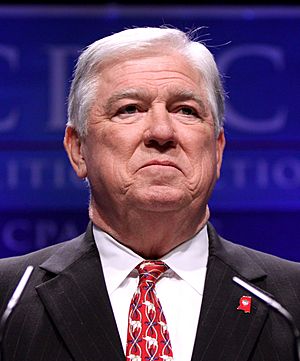

In 2007, Governor Haley Barbour said the museum was "overdue." His support helped many lawmakers agree to fund the project. They approved $500,000 to start planning.

Choosing a Location

A group of 39 people was formed to pick the best spot for the museum. Many cities and colleges offered locations. There was a lot of discussion about where it should be.

In 2008, the group decided that the museum should be built on the Tougaloo College campus. However, this decision caused some disagreement. People debated if this was the best choice.

Delays and New Plans

After the site was chosen, the museum project faced delays for about three years. This was due to a tough economy and other issues. Many people worried the museum would never be built.

By 2010, Governor Barbour decided to push for the museum again. He said it was important to build it. He suggested building the Civil Rights Museum next to a planned Museum of Mississippi History. This idea would save money and create two important museums side-by-side.

In April 2011, the state government finally approved funding. They agreed to sell $20 million in state bonds to build the museum. They also planned to raise more money from private donations. This was a big step forward!

Designing the Museum

In December 2011, African American architect Philip Freelon was chosen to design the building. He worked with Jeffrey Barnes from Dale Partners Architects.

The public was invited to share their ideas for the museum. People wanted a building that looked special and an inside that felt respectful. They also wanted the exhibits to tell the true story of the civil rights movement.

In 2012, a new design was shown. It connected the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum to the Museum of Mississippi History. They would share a main entrance and lobby. The civil rights museum would have seven main areas, called galleries. It would also feature a tall sculpture in the middle and two theaters.

Jacqueline K. Dace became the museum's first director in 2012. Later, Pam Junior became the director in 2017. In 2023, Michael Morris took over as the new Director for both the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum and the Museum of Mississippi History.

Opening Day

The Mississippi Civil Rights Museum opened on December 9, 2017. It was a historic day for Mississippi and the nation. It stands next to the new Museum of Mississippi History. They share a common entrance, making it easy to visit both.

The museum takes visitors on a journey through history. You start by learning about slavery and how African American communities grew after the Emancipation Proclamation. Then, you enter a powerful room with a tree sculpture. This tree represents Jim Crow laws and the terrible acts of violence, like lynching, that happened. The names of over 600 African Americans who were lynched in Mississippi are carved into memorial stones.

The first parts of the museum feel a bit small. This is done on purpose to show how people felt restricted during those times. As you move through, the spaces become more open. These areas focus on the 30 years when Mississippi was a key place in the civil rights struggle. You can see exhibits about people who were killed for their activism.

Many civil rights leaders praised the museum. They said it tells an "honest depiction of Mississippi's past." Reviewers from newspapers like The New York Times also loved it. They said the museum "rivets attention" and "refuses to sugarcoat history."

Dedication Event

Mississippi Governor Phil Bryant invited President Donald Trump to the museum's dedication. This invitation caused some debate. Many African Americans and civil rights leaders felt that President Trump's views on race did not match the museum's message.

Because of this, some important leaders chose not to attend the public ceremony. These included U.S. Representative John Lewis, a famous civil rights activist, and U.S. Representative Bennie Thompson.

President Trump visited the museum privately on December 9. He took a short tour and gave a speech to a smaller group. He spoke about civil rights activist Medgar Evers, who was killed in Jackson in 1963. Outside, people held protests with signs and chants.

Inside the Museum

Layout and Galleries

The Mississippi Civil Rights Museum has a lobby and eight galleries. The design is circular, with the galleries around a central area. The idea is to guide visitors through darker parts of history into brighter, more hopeful spaces. Many galleries are small and dimly lit, with exhibits from floor to ceiling. The bright central rotunda is the heart of the museum.

- Gallery 1: "Mississippi Freedom Struggle" This gallery shows the history of Black people in Mississippi. It covers their lives from when African slaves first arrived until the end of the Civil War.

- Gallery 2: "Mississippi in Black and White" This section covers the time between the Civil War and 1941. It focuses on difficult topics like lynching, the Ku Klux Klan, and Jim Crow laws. Five monuments list the names of those who were lynched. An artificial tree with images from the Jim Crow era stands in this gallery.

- Gallery 3: "This Little Light of Mine" This is the central gallery under the museum's rotunda. It has a special sculpture called This Little Light of Mine. This sculpture has lighted panels that show the faces of activists who died during the civil rights movement.

- Gallery 4: "A Closed Society" This gallery shows how the civil rights movement grew from 1941 to 1960. It has small theaters that show films about the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education court case and the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till. You can also see the doors from Bryant's Grocery, where the incident with Emmett Till happened.

- Gallery 5: "A Tremor in the Iceberg" This section covers early civil rights struggles from 1960 to 1962. It has exhibits about the Freedom Riders and a model of a jail cell. A film tells the story of Medgar Evers, and his rifle is on display nearby.

- Gallery 6: "I Question America" This gallery focuses on the important years of 1963 and 1964. It includes a recreated church where you can watch a film about Freedom Summer. You can also see a cross burned by the Klan and pieces of stained glass from a bombed church.

- Gallery 7: "Black Empowerment" This section shows the successes and challenges of the movement from 1965 to 1975. It displays the bullet-ridden truck of Vernon Dahmer, a civil rights leader killed by the Ku Klux Klan.

- Gallery 8: "Where Do We Go From Here?" This final gallery asks visitors to think about the future of minority citizens in Mississippi. Interactive exhibits let you share your own thoughts and ideas.

This Little Light of Mine Sculpture

The amazing This Little Light of Mine sculpture is a key part of the museum. It was designed to show that "everybody has a light" or a contribution to make. It also reminds us that there is always hope, even in dark times.

The sculpture is 40 feet tall and hangs from the ceiling. It is made of fabric-covered aluminum blades with many LED lights. These lights are controlled by a computer.

As more people enter the central gallery, more lights on the sculpture flicker. Every 30 minutes, the songs This Little Light of Mine and Ain't Gonna' Let Nobody Turn Me Around play. The lights move and flicker with the music. Children, college students, and adults recorded these songs.

New Leadership

On July 11, 2023, Michael Morris became the new Director of the Two Mississippi Museums. This includes both the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum and the Museum of Mississippi History. He replaced Pamela D.C. Junior, who retired. Michael Morris studied history and political science at Jackson State University. He has worked with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History since 2016.

Visitors to the Museum

When the museums first opened, officials thought about 180,000 people would visit in the first year. By early 2018, over 80,000 people had already visited. This showed how popular the museums were. As of 2023, more than 500,000 people have visited the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum since it opened in December 2017.

See also

- List of museums focused on African Americans

- Civil Rights Movement

- Mississippi Department of Archives and History

- Museum of Mississippi History

- Tugaloo College

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |