Missouri Lumber and Mining Company facts for kids

| Industry | Lumber |

|---|---|

| Fate | Closed |

| Founded | 1880 |

| Founders | O.H.P. Williams, E.B. Bishop, J.L. Livingston, Jahu Hunter |

| Defunct | 1919 |

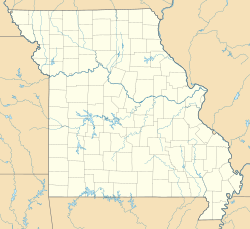

| Headquarters | Grandin, Missouri, United States (until 1910) |

| Products | Dimensional lumber, shingles, lath |

|

Historic Resources of the Missouri Lumber and Mining Company

|

|

| Location | Grandin, Missouri |

|---|---|

| Area | 9.9 acres (4.0 ha) |

| Built | 1888-1909 |

| MPS | Missouri Lumber and Mining Company MRA |

| NRHP reference No. | 64000398 |

| Added to NRHP | October 14, 1980 |

The Missouri Lumber and Mining Company (MLM) was a huge company that cut down trees and made lumber. It was based in Grandin, Missouri, in the southeastern part of the state. The company was started by lumbermen from Pennsylvania. They wanted to use the many trees in the Missouri Ozarks to make lumber for building homes and towns as the U.S. expanded westward.

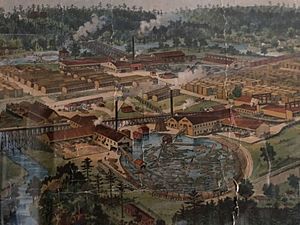

MLM built its main operations in Grandin, which was a company town. This town was built starting around 1888. The lumber mill in Grandin became the biggest in the country around 1900. Grandin's population grew to about 2,500 to 3,000 people.

However, as the trees ran out, the company had to leave Grandin around 1910. MLM continued to cut timber in other parts of Missouri for another ten years. Many of the buildings left in Grandin were later recognized as important historical sites. They were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. This was because MLM played a big part in Missouri's technology and economy.

Contents

Starting the Company

In the 1860s, O.H.P. Williams, who was in the lumber business, and his son-in-law, Elijah Bishop Grandin, heard about the valuable trees in Missouri. They started buying land in Ripley County. In the 1870s, they bought another 30,000 acres in Carter County. They paid about $1 per acre.

They teamed up with two other men from Pennsylvania, John Livingston Grandin (Elijah's brother) and Jahu Hunter. Together, they formed the Missouri Lumber and Mining Company. The company was officially started in 1880.

The founders thought the local people would be happy to work for the company because they didn't have many jobs. They also liked that Missouri winters were milder than Pennsylvania's. This meant they could work all year. Being close to the Great Plains states was also a plus. This area had a growing population but few trees, so they needed a lot of lumber.

The four partners stayed in Pennsylvania. They hired John Barber White, an experienced mill operator, to move to Missouri and manage the company. MLM bought thousands more acres of land in other counties. This land had lots of short-leaf Southern yellow pine trees and some hardwoods. White even bought some land for as little as five cents per acre.

The first lumber mill was built on the Black River. It was named White's Mill after the manager. This mill could produce six million board feet of lumber each year. But it was hard to get the lumber to customers. The closest railroad was 10 to 15 miles away. Workers had to use oxcarts to move the lumber to the train station.

The company tried for years to get a direct railroad line to the mill. But the railroad company refused. Even though MLM owned 100,000 acres of timberland nearby, the mill couldn't work at its full capacity. It closed in 1884, and 125 employees lost their jobs.

Building a New Mill

After closing the first mill, the company focused on Carter County. They had grown their land there to 100,000 acres. They found a good spot for a new mill and worked out a deal with the Kansas City, Fort Scott and Memphis Railway (KFS&M).

The railroad agreed to build an 81-mile track to MLM's land. In return, MLM promised to ship a lot of lumber using their trains. The new track, called the Current River Railroad, was finished in 1888. Later that year, another railroad line was extended from the east. This helped MLM send lumber to eastern markets too.

MLM built its new mill 10 miles south of the old White's Mill. It was next to Toliver Pond. This pond was a flooded sinkhole that could hold many logs waiting to be cut. The old White's Mill was taken apart and moved to this new spot. They even brought a locomotive (train engine) by taking it apart and using ox-teams to haul it 22 miles. This huge effort created a $250,000 complex of mills and kilns (ovens for drying wood).

Life in Grandin

Just west of the new mill, MLM built the town of Grandin. It was named after company founder E.B. Grandin. In 1889, the company had 175 employees. These included local people and skilled workers like sawyers who came from other areas. Grandin was a private company town and served as the company's main office for about 20 years.

A company architect designed the town. It had a main street with a company store, a hospital, a hotel, and other businesses. These buildings were surrounded by big lawns and pretty landscaping. There were also residential streets planned for up to 1000 houses. Outside of town were train repair shops and other workshops. Between the town and the mills was an 80-acre lumberyard. The company's main office building was like the town's bank. Employees were paid there once a month.

A Time of Growth

When the railroad arrived in June 1888, there were six million board feet of lumber ready to be shipped from Grandin. By 1892, the mill produced 32 million board feet. After 1895, it averaged 60 million board feet each year. More mills were added, and by 1894, some newspapers said it was the biggest mill in the country.

MLM used a large network of tram railways to move logs to the mill. These tracks were the same size as regular train tracks. They had 300 log cars and 6 locomotives. This allowed log cars to travel directly to the mill on the main railroad lines. The company also floated logs down rivers and streams, especially the Current River. Mules would drag logs to the riverbank, where they floated downstream in groups up to 15 miles long.

Only trees that were 11 inches or wider were cut down. The largest trees were almost four feet wide! All logs were left to soak in Toliver Pond for several days. This helped remove dirt that could dull the saw blades. The mills used different types of saws, all powered by steam. Besides regular lumber, they also made shingles (for roofs) and lath (thin strips of wood).

The company called its pine wood "Beaver Dam Soft Pine" and used a beaver as its trademark. This name became well-known across the U.S. MLM lumber was sold from Ohio to the plains states. Most of it went west of the Mississippi River. In 1901, half of its lumber went to dealers in Kansas City.

In 1890, John Barber White became president of a group that worked to get better rates from railroads and set standard prices for lumber. White moved his office to Kansas City in 1891, where other big lumber companies were located. He helped bring together lumber companies in the region. The company became so powerful that it could raise lumber prices ten times in 1899. It even helped control lumber prices across the country.

The company grew, employing about 1000 people in Grandin by 1900. This number peaked at 1500 five years later. One out of every six people in Carter County worked for MLM. The company hired skilled workers from other areas and mostly used local people for less skilled jobs. MLM also had smaller operations in Hunter and Fremont.

Life in the Company Town

MLM built homes in Grandin that it rented to employees and their families. They built over 475 houses, renting them for $1 per room per month. Many of these homes were two stories tall, painted, and had sloped roofs. They often had front porches and extra rooms added to the back.

Single women lived in a company-owned boarding house. This allowed the company to keep an eye on their behavior. There were also two boarding houses for men. Rent for these boarding houses was $18 per month, which included meals. Most single men lived in simpler cabins that rented for $2 to $2.50 per month. These cabins were sometimes built somewhere else and then brought to Grandin by train. Larger homes for company leaders rented for $5 to $10 monthly.

Because MLM owned all the housing in Grandin, it had a lot of control over the town. The company helped widows of workers who died on the job, usually for up to two years. MLM acted like the people of Grandin were its responsibility, but it also made sure to stay profitable.

In 1906, MLM built a sidewalk on the town's main street to help businesses. But they refused to add sidewalks on the residential streets. The company also built the town's school and was involved in how it was run. Company officials often led the school board and approved hiring teachers.

MLM brought telephone service to Grandin to help the company communicate better. At first, they didn't allow phones in private homes, but they later changed their minds. The company also provided other things for the town, like a library and churches for different religions. They even paid the ministers' salaries. MLM supported other groups, like the Knights of King Arthur, to help create a healthy and hardworking community. They also provided fun things like recreation facilities, baseball teams, and even an ice-skating rink.

Around 1890, MLM opened a small hospital with doctors. This was to keep its workers and their families healthy and productive. Employees paid a monthly fee ($0.75 for single workers, $1.25 for families) for unlimited healthcare. MLM was one of the first companies to offer health care to its employees. The clinic grew to have ten staff members, including a dentist. The company even had a small mobile health clinic on a train car. This allowed them to bring healthcare to the work camps in the forest. Serious injuries and deaths were common, especially among railroad workers.

Most jobs were held by men, but MLM hired many women as stenographers (people who write down what is said) and clerks. This made the company a leader in having women work in office jobs in the 1890s. The company required all workers to have good character references. Grandin's population reached its highest point with 2,500 to 3,000 people. About 1,200 of them worked directly for MLM.

The Company's End

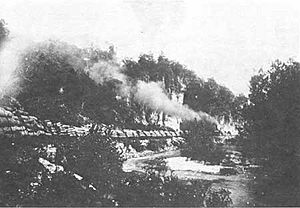

In 1900 and 1901, the Grandin mill was considered the largest in the world. It could produce 75 million board feet of lumber each year. However, the most it ever produced was just under 66 million in 1901. Production quickly dropped to about 37 million board feet in 1904. A fire in 1905 destroyed a smaller mill. After that, the main mill started working 24 hours a day, using 90 train cars of logs daily.

Over time, it became harder to buy timberland and cut trees for a good profit. Land prices went up quickly as landowners realized how valuable their trees were. It was also important for timberland to be close to the railroad. Building logging tracks through the difficult land cost about $1,000 per mile.

Most of the trees in the county were cut down. Then, the land was often used for farming. The lumber industry didn't manage the forests to grow new trees for the future. Missouri's tax laws also made it hard to replant trees and wait decades for them to grow. So, the land had to be sold after the first harvest. Except for a boost during World War II, yearly lumber production in the region kept going down until the 1960s.

By 1900, there were few trees left near the Grandin mill. So, the company moved its operations north, buying land mainly in Shannon County. A new railroad owner offered a lower price for lumber shipped from northwest Shannon County. MLM built the Grandin and Northwestern Railroad to connect its logging camp in Shannon County to the Current Railroad. This was more than 60 miles from Grandin.

By 1906, the company started planning to leave Grandin. The mill was only working four days a week in late 1907. Even with the discounted shipping rate, it was too expensive to ship logs from Shannon County all the way to Grandin for processing. This was especially true after lumber prices dropped during the recession of 1907. As the supply of nearby trees quickly disappeared, the last logs in the area were cut in 1909. The mill closed in 1910. The mill and many houses from Grandin were moved to the new mill location, which became West Eminence.

The last meeting of MLM's owners in Grandin was in September 1910. The company sold the remaining homes and lots in Grandin for $50 to $100, mostly to individuals. MLM continued to operate in West Eminence and Hunter for about another ten years. The company's owners also had timberland in Louisiana and thought about buying land in the Pacific Northwest. However, these operations were run by different companies. MLM's work in Missouri ended in 1919 when it sold the West Eminence mill.

MLM had more deforested land than it could sell and was still getting rid of land into the 1930s. At one point, MLM even thought about giving land to the government to create a national park.

Historic Buildings

The Missouri Lumber and Mining Company was very important to Missouri's timber industry and the national economy. It used new technology and operated on a scale never seen before in the Ozark region. The buildings that are still standing from the company's time in Grandin (1888-1909) are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. They are examples of how technology helped shape Missouri's history.

These historic buildings were added to the National Register in 1980. They include Toliver Pond and 29 other buildings. Six of these buildings are close together and are part of the Sixth Street Historic District.

The six houses in the historic district are listed under the district's number. Toliver Pond and the other 23 buildings have their own individual numbers. All 30 places are described in a special report about MLM's historic resources.

Houses in the Sixth Street Historic District

These houses are all part of the Sixth Street Historic District:

| Name | Image | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Rongey House | 6th and Oak Sts. 36°49′49″N 90°49′39″W / 36.830149°N 90.827544°W |

A two-story house with wooden siding, a sloped roof, and an addition in the back. A porch wraps around the north and west sides. | |

| Joe Deaton House | 6th St. 36°49′48″N 90°49′38″W / 36.829880°N 90.827240°W |

A one-story house that was made bigger by adding a wing with a sloped roof. The house has wooden siding and a front porch. | |

| Clarence Graham House | 6th and Elm Sts. 36°49′47″N 90°49′37″W / 36.829797°N 90.826872°W |

A two-story house with wooden siding, a front porch, and a one-story wing in the back. The roofs are sloped and made of corrugated metal. | |

| Everett Nance House | 6th and Elm Sts. 36°49′46″N 90°49′36″W / 36.829523°N 90.826564°W |

A two-story house with a sloped roof and wooden siding. It has a one-story front porch and a two-story addition on the southwest corner. | |

| Cynthia McKinney House | 6th St. (between Ash & Elm) 36°49′46″N 90°49′34″W / 36.829513°N 90.826201°W |

A two-story house with a sloped roof, wooden siding, and a two-story wing with a sloped roof in the back. | |

| Bill McDowell House | 6th and Ash Sts. 36°49′46″N 90°49′33″W / 36.829314°N 90.825760°W |

A two-story house with wooden siding, a sloped roof, a front porch, and an addition in the back. |

Map of Historic Buildings

Images for kids