Muscogee Nation facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Muscogee Nation

Este Mvskokvlke (Creek)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

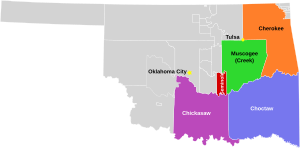

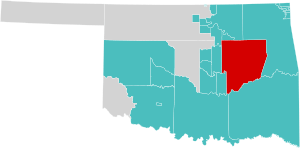

Location (red) in the U.S. state of Oklahoma

|

|||

| Established | August 7, 1856 | ||

| Capital | Okmulgee | ||

| Population | |||

| • Total | 86,100 | ||

| Demonym(s) | Muscogee | ||

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) | ||

Flag

|

|

Seal of the Muscogee Nation

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 80,591 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Muscogee |

|

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Muscogee people, Alabama, Hitchiti, Koasati, Natchez Nation, Shawnee, Seminole, and Yuchi |

The Muscogee Nation, also called the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, is a Native American tribe. It is officially recognized by the U.S. government. The tribe is based in Oklahoma.

The Muscogee Nation comes from the historic Muscogee Confederacy. This was a large group of Native American groups from the Southeast. Their official languages include Muscogee, Yuchi, Natchez, Alabama, and Koasati. Muscogee has the most speakers.

They call themselves Este Mvskokvlke. In the past, European Americans often called them one of the Five Civilized Tribes. These tribes were known for adopting some European-American customs.

The Muscogee Nation is the largest of the Muscogee tribes recognized by the government. Other groups like the Alabama, Koasati, Hitchiti, and Natchez people are also part of this nation. Even the Shawnee and Yuchi people, who had different languages and cultures, are enrolled here.

Other Muscogee groups recognized by the government include the Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town, Kialegee Tribal Town, and Thlopthlocco Tribal Town in Oklahoma. Also, the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, and the Poarch Band of Creek Indians in Alabama are recognized.

Contents

Muscogee Nation's Land and Government

The main office of the Muscogee Nation is in Okmulgee, Oklahoma. This city is the center of their tribal government. In 2020, the United States Supreme Court confirmed the Muscogee Nation's reservation status. This means their reservation in Oklahoma still exists.

The court ruling confirmed the Nation's right to govern its citizens. This includes citizens living in Creek, Hughes, Okfuskee, Okmulgee, McIntosh, Muskogee, Tulsa, and Wagoner counties in Oklahoma.

Who Can Be a Citizen?

In 2019, there were over 87,000 Muscogee citizens. Most of them, about 65,000, lived in Oklahoma. California and Texas also had many citizens. Tulsa, Oklahoma, had the most citizens in one city.

The population is split evenly between females and males. Most citizens are between 18 and 54 years old. To become a citizen, you must have Muscogee ancestry. You need to show a direct link to someone listed on the 1906 Dawes Roll. This is done using birth or death certificates.

A Citizenship Board with five members helps people with this process. They research family histories to confirm who can be a citizen. In 2023, a Muscogee court decided that descendants of people enslaved by Muscogee Nation members can also become citizens.

Services for Citizens

The Muscogee Nation offers many services to its people. They have their own housing department. They also issue vehicle license plates. Their health division works with Indian Health Services. They run the Creek Nation Community Hospital and several clinics.

They also have programs for job training and nutrition. These programs help children and older people. There are also special programs for diabetes, tobacco prevention, and caregivers.

The Nation has its own police force, called the Lighthorse Tribal Police Department. It has 43 active employees. The tribe also has a program to help with child support payments.

The Mvskoke Food Sovereignty Initiative is another important program. It teaches tribal members to grow their own traditional foods. This helps with health, the environment, and sharing knowledge between generations.

The Muscogee Nation also has a Communications Department. They publish a newspaper called the Mvskoke News twice a month. They also have a weekly TV show called Native News Today.

Growing the Economy

The tribe manages a budget of over $290 million. They have more than 4,000 employees. These employees provide services within the Nation's land.

The tribe runs both gaming (casino) and non-gaming businesses. Non-gaming businesses are managed by Muscogee Nation Business Enterprise (MNBE) and Onefire. These groups plan and operate business projects for the tribe.

For gaming, the tribe has 9 casinos. The largest is the River Spirit Casino Resort in Tulsa. Money from all businesses is used to start new businesses. It also helps support the well-being of the tribe. The Muscogee Nation also operates two truck stops.

Important Buildings and Places

The Creek National Capitol, also known as the Council House, was built in 1878. It is located in downtown Okmulgee. This large stone building has two entrances and many windows. A square tower, called a cupola, sits on top. It used to hold bells to call tribal leaders to meetings.

The building was the meeting place for the Muscogee Nation's government. This lasted until 1907, when Oklahoma became a state. After that, the building was used for other things. It was even the Okmulgee County Courthouse for a time.

In 1961, the building was named a National Historic Landmark. This means it is a very important historical place. In 1979, the Muscogee Nation gained full control over its own affairs again. They adopted a new constitution.

The Council House was fully repaired between 1989 and 1992. It reopened as a museum. In 2010, the Muscogee Nation bought the building back. Today, it is a museum about tribal history. It is open to everyone and shows Native American history and culture.

College of the Muscogee Nation

In 2004, the Muscogee Nation started its own college in Okmulgee. It is called the College of the Muscogee Nation (CMN). It is one of only 38 tribal colleges in the United States.

CMN is a two-year college. It offers degrees in areas like Tribal Services, Police Science, and Native American Studies. Students can also take classes in the Mvskoke language, Native American History, and Tribal Government.

The college offers financial aid and housing on campus. In 2018, nearly 200 students were enrolled. Many Muscogee citizens are interested in attending the tribal college.

A Look at History

The Muscogee people and their descendants were forced to move from their homes in the Southeast. This happened in the 1830s during the Trail of Tears. They were moved to what is now Oklahoma. They signed a new treaty with the U.S. government in 1856.

During the American Civil War, the tribe split. Some allied with the Confederacy, while others supported the Union. There were battles between these groups in Indian Territory. Many Muscogee people died trying to find safety in Kansas.

After the Civil War, the Union made new peace treaties with the tribes. The Treaty of 1866 required the Creek to end slavery. It also said that formerly enslaved people could become tribal citizens. They would have voting rights and shares of land.

The Muscogee created a new government in 1866. They chose Okmulgee as their new capital. In 1867, they approved a new constitution. They built their capitol building in 1867 and made it bigger in 1878.

In the late 1800s, the Nation built schools, churches, and public buildings. This was a time when the tribe had more control over its own affairs.

Around 1900, the U.S. Congress passed laws like the 1898 Curtis Act and the Dawes Allotment Act. These laws tried to break up tribal governments and communal land. The goal was to make Native Americans live more like European Americans. This also led to Native Americans losing much of their land.

The government then sold "surplus" land to non-Natives. This meant the Muscogee and other tribes lost control of a lot of their land. In 1907, Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory became the state of Oklahoma. By then, the Muscogee had lost millions of acres.

Later, in the 20th century, Muscogee communities began to reorganize. Some groups that had stayed in the Southeast gained federal recognition. These include the Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town and the Poarch Band of Creeks.

The Muscogee Nation itself did not reorganize until 1970. In 1979, they approved a new constitution. A court case in 1976, Harjo v. Kleppe, helped tribes gain more control over their own affairs. Today, the Nation has over 58,000 members.

Notable Muscogee Nation People

- Fred Beaver (1911–1980), Muscogee/Seminole painter

- R. Perry Beaver (1938-2014), principal chief and football coach

- Acee Blue Eagle (1909-1959), actor, artist, and educator

- Ernest Childers (1918–2005), first Native American to receive the Medal of Honor in World War II

- Eddie Chuculate (b. 1972), Muscogee/Cherokee journalist and writer

- Sarah Deer (b. 1972), lawyer and professor

- Thomas Gilcrease (1890–1962), oilman and museum founder

- Chitto Harjo (1846-1911), traditionalist leader

- Joy Harjo (b. 1959), poet and jazz musician, first Native American United States Poet Laureate

- Joan Hill (1930–2020), painter

- Jack Jacobs (1919–1974), football player

- William Harjo LoneFight (b. 1966), author and cultural activist

- Timothy Long, pianist and conductor

- Louis Oliver (1904–1991), poet

- Jim Pepper (1941–1992), Muscogee/Kaw jazz musician

- Grant-Lee Phillips (born 1963), singer-songwriter

- Pleasant Porter (1840–1907), Principal Chief

- Alexander Posey (1873—1908), poet and journalist

- Allie P. Reynolds (1917-1994), professional baseball player

- Will Sampson (1933–1987), film actor

- Cynthia Leitich Smith (born 1967), children's book author

- Dana Tiger (b. 1961), artist

- Johnny Tiger, Jr. (1940–2015), painter and sculptor

- France Winddance Twine (born 1960), professor of sociology

- Micah Ian Wright (born 1969), writer and film director

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |