Neil Hamilton Fairley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir Neil Hamilton Fairley

|

|

|---|---|

Brigadier Neil Hamilton Fairley

|

|

| Born | 15 July 1891 Inglewood, Victoria, Australia |

| Died | 19 April 1966 (aged 74) Sonning, Berkshire, England |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Service/ |

Australian Army |

| Years of service | 1915–1946 |

| Rank | Brigadier |

| Service number | VX38970 |

| Commands held | Director of Medicine at Allied Land Forces Headquarters 14th General Hospital |

| Battles/wars | First World War: |

| Awards | Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire Commander of the Order of St John Mentioned in Despatches (2) Fellow of the Royal Society Cameron Prize for Therapeutics of the University of Edinburgh (1947) Manson Medal (1950) |

| Relations | Gordon Hamilton-Fairley (son) |

Brigadier Sir Neil Hamilton Fairley (born July 15, 1891 – died April 19, 1966) was an amazing Australian doctor, scientist, and army officer. He played a huge role in saving thousands of soldiers' lives during wars by fighting diseases like malaria and others.

Fairley studied at the University of Melbourne. He joined the Australian Army Medical Corps in 1915. He looked into a serious outbreak of meningitis in army camps in Australia. While working at the 14th General Hospital in Cairo, he studied schistosomiasis (a disease caused by parasites). He created new tests and treatments for it. Between the two World Wars, he became a famous expert in tropical medicine.

Fairley returned to the Australian Army during the Second World War. He became the Director of Medicine. He was very important in planning for the Battle of Greece. He convinced the British commander, General Sir Archibald Wavell, to change his plan. This helped reduce the danger of malaria for the troops. In the South West Pacific Area, Fairley was in charge of getting all Allied forces to work together against malaria and other tropical diseases. He warned everyone about the dangers of malaria. He persuaded leaders in the United States and United Kingdom to make a lot more anti-malaria medicines. Through his research team, he quickly developed new drugs. Fairley convinced the Army that the new drug atebrin worked well. He also persuaded commanders to make sure soldiers took the medicine.

After the war, Fairley went back to London. He became a doctor at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases. He also became a professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He got very sick in 1948 and had to stop being a professor. But he kept working as a doctor and served on many important committees. He became a respected "elder statesman" in tropical medicine.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Neil Hamilton Fairley was born in Inglewood, Victoria, Australia, on July 15, 1891. He was one of six sons. Four of his brothers also became doctors.

Neil went to Scotch College, Melbourne, where he was the top student. He then went to the University of Melbourne. He earned his medical degree with top honors in 1915. He also won the Australian high jumping championship and played tennis for Victoria.

First World War Efforts

Fairley joined the Australian Army Medical Corps as a captain in August 1915. He worked at the Royal Melbourne Hospital. He studied a serious outbreak of meningitis in army camps. His first published paper was about this disease. In 1916, he helped write a report about 644 cases, where more than half were deadly before antibiotics existed.

Fairley joined the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in August 1916. He traveled to Egypt and joined the 14th General Hospital in Cairo. There, he met Major Charles Martin, a famous professor.

While in Egypt, Fairley investigated schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia. This disease was caused by contact with fresh water where certain snails lived. Soldiers were told not to swim in fresh water, but they didn't always understand the danger. Fairley created a special test for the disease. He also found that the worms in the body could be cured with a medicine called tartaric acid. Fairley also studied typhus, malaria, and dysentery.

Fairley was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1919. He commanded the 14th General Hospital for a while. For his work in the First World War, Fairley was mentioned in official reports. He was also made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire. His award recognized his "brilliant work in Pathology" and his research on bilharzia, which was "of untold value."

Between the World Wars

After the war, Fairley worked at the Lister Institute in London. He became a member of the Royal College of Physicians of London. He also earned a Diploma of Public Health from the University of Cambridge. He returned to Australia in 1920. He worked at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research. He developed a test for echinococcosis, another parasitic disease.

Fairley then took a job in Bombay, India, in 1921. He was supposed to be a professor of tropical medicine. While in India, he continued his research on schistosomiasis. He also did important work on Guinea worm disease (dracunculiasis). His main interest was tropical sprue, a disease that affects digestion. He even caught the disease himself and made progress in treating it. He returned to the United Kingdom in 1925 to recover.

In 1928, Fairley moved to London. He became a doctor at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases. He also taught at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He opened his own medical practice too. He researched filariasis, another parasitic disease. He also did important work on blackwater fever, a severe form of malaria. Since malaria was rare in the UK, he visited a research lab in Greece every year. He discovered a new blood pigment called methaemalbumin. For his scientific achievements, Fairley was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1942.

Second World War Efforts

Middle East Campaigns

When the Second World War started, Fairley was asked to be a consulting doctor for the Australian Army. He joined the Second Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in Cairo in September 1940. He also helped the British Army with tropical diseases.

In January 1941, the British Army planned operations in Greece. Fairley and his British colleague, Colonel John Boyd, wrote a report. They warned about the serious risks of malaria, based on past experience. They even suggested that the Germans might try to trap the Allies in a summer campaign where malaria could destroy them. The British commander, General Sir Archibald Wavell, didn't like their report at first. But after meeting Fairley and Boyd, he understood the danger. The plan was changed to move Allied forces further south, away from areas where malaria was very common.

Fairley also dealt with an outbreak of dysentery among troops in Egypt. He had an experimental medicine called sulphaguanidine. This drug was given to a very sick patient who was not expected to live, and the patient quickly recovered. Out of over 21,000 Australian soldiers who got dysentery, only 21 died.

Malaria became a problem again in the Syria-Lebanon Campaign. The Australian Army created special malaria control units. Swamps and wet areas were drained, and mosquito breeding grounds were sprayed. In 1941, there were 2,435 cases of malaria in the AIF. Soldiers used quinine to prevent it. Fairley advised treating relapses with quinine and then atebrin and plasmoquine. For his work in the Middle East, Fairley was mentioned in official reports again. He was also made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire for his "immense and specialised knowledge of tropical diseases."

South West Pacific Campaigns

When Japan entered the war, Fairley flew to Java in January 1942. He knew that Java produced most of the world's quinine. He arranged to buy all available quinine, about 120 tons. However, most of it never reached Australia. Fairley himself left Java just before it fell.

In April 1942, Fairley became the Director of Medicine at Allied Land Forces Headquarters in Melbourne. He soon faced many medical emergencies during the Kokoda Track campaign. An outbreak of dysentery was stopped because Fairley quickly sent all available sulphaguanadine to New Guinea. Every soldier with diarrhea was given the drug, and the outbreak was controlled in ten days.

But Fairley's biggest worry was malaria. Most soldiers didn't understand how to prevent malaria. There were also not enough medicines, nets, and insect repellents. This led to a medical disaster. From October 1942 to January 1943, the Army reported 4,137 battle injuries. But there were 14,011 cases of tropical diseases, with 12,240 from malaria. General Thomas Blamey said, "Our worst enemy in New Guinea is not the Nip—it’s the bite."

This led Blamey to send Fairley on a special trip to the United States and the United Kingdom in September 1942. Fairley's job was to get more anti-malaria supplies. The trip was a success. Fairley got the supplies needed and sped up deliveries. He made the world's military and civil leaders understand how important malaria control was.

It was estimated that the Allies would need 200 tons of atebrin each year. Efforts were made to increase production. The Army used a mix of quinine, atebrin, and plasmoquine to treat malaria. The requested drugs and supplies started arriving in December 1942.

Fairley suggested creating a group to coordinate all Allied forces' efforts against tropical diseases. General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander, created the Combined Advisory Committee on Tropical Medicine, Hygiene and Sanitation in March 1943. Colonel Fairley was its chairman. The committee made many recommendations about training, discipline, equipment, and procedures. These became official orders for all commands.

Fairley's idea to use atebrin to prevent malaria was accepted. In March 1943, the Australian Army switched from quinine to atebrin for prevention. The biggest problem was a shortage of atebrin. The drug also made skin and eyes turn yellow, but this was accepted during wartime. In rare cases, it could cause other problems, but atebrin was still much safer than quinine. Blackwater fever, which was often deadly, disappeared completely.

Fairley knew that much was still unknown about malaria. He wanted to find a drug that could be made in Australia. He decided to set up a research unit in Cairns to study malaria. The LHQ Medical Research Unit started its work in June 1943.

The LHQ Medical Research Unit used human volunteers from the Australian Army. These volunteers were infected with malaria and then treated with different drugs. They received three weeks' leave and a thank-you certificate from General Blamey. The unit researched quinine, sulphonamides, atebrin, plasmoquine, and paludrine.

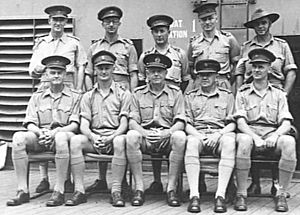

In June 1944, a conference was held in Atherton, Queensland. Fairley, who had been promoted to brigadier in February 1944, shared the results of the work in Cairns. Other officers talked about ways to reduce disease among the soldiers.

The army used strict rules to make sure soldiers took their atebrin tablets. Officers would even place the tablets in the men's mouths. This largely helped reduce malaria cases. However, in the Aitape-Wewak campaign, the 6th Division had a malaria outbreak despite their best efforts. Fairley was called back and ordered to investigate. The epidemic was eventually controlled by doubling the atebrin dosage. Fairley discovered that a strain of malaria had become resistant to atebrin. This ability of malaria to become resistant would have big effects after the war.

Later Life and Legacy

After the war, Fairley moved to Britain. He became a consulting doctor at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases. He also became a professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. His early research after the war continued his work on malaria. He became very ill in 1948, and his health slowly got worse. He had to resign from his professorship. But he continued his medical practice and served on many committees. He became a respected "elder statesman" in tropical medicine. For his great service, he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1950.

Fairley's declining health led him to move from London. He died on April 19, 1966, and was buried in Sonning, Berkshire. He was survived by his wife and their two sons, who were both doctors. He also had a son from his first marriage who became an Australian Army officer. His son Gordon Hamilton-Fairley became a famous cancer doctor.

Sir William Dargie painted a portrait of Fairley in 1943. Another portrait by Dargie from 1960 and one by Nora Heysen from 1945 are in the Australian War Memorial. Fairley's important papers are now kept at the Australian War Memorial. He is remembered by the Neil Hamilton Fairley Overseas Clinical Fellowship. This helps doctors get special training in clinical research.

Medical Awards and Prizes

- 1920 Dublin Research Prize

- 1921 David Syme Research Prize and Medal

- 1931 Chalmers Medal for Research in Tropical Medicine

- 1945 Bancroft Memorial Medal

- 1946 Richard Pierson Strong Medal, American Foundation of Tropical Medicine

- 1947 Cameron Prize for Therapeutics of the University of Edinburgh

- 1948 Moxon Medal, Royal College of Physicians

- 1949 Mary Kingsley Medal, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

- 1950 Manson Medal, Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

- 1951 James Cook Medal, Royal Society of NSW

- 1957 Buchanan Medal, Royal Society of London

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |