Niels Henrik Abel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Niels Henrik Abel

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 5 August 1802 Nedstrand, Denmark–Norway

|

| Died | 6 April 1829 (aged 26) Froland, Norway

|

| Nationality | Norwegian |

| Alma mater | Royal Frederick University (BA, 1822) |

| Known for | Abel's binomial theorem Abel equation Abel equation of the first kind Abelian extension Abel function Abelian group Abel's identity Abel's inequality Abel's irreducibility theorem Abel–Jacobi map Abel–Plana formula Abel–Ruffini theorem Abelian means Abel's summation formula Abelian and tauberian theorems Abel's test Abel's theorem Abel transform Abel transformation Abelian variety Abelian variety of CM-type Dual abelian variety |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Academic advisors | Bernt Michael Holmboe |

| Signature | |

Niels Henrik Abel (5 August 1802 – 6 April 1829) was a brilliant Norwegian mathematician. He made many important discoveries in different areas of math. His most famous achievement was proving that it's impossible to solve a certain type of math problem, called the general quintic equation, using simple algebra. This was a really tough math problem that no one had solved for over 250 years!

Abel also made new discoveries about special math functions called elliptic functions and Abelian functions. He did most of his amazing math work in just six or seven years. Sadly, he lived a tough life and died young at 26 from a sickness called tuberculosis.

The French mathematician Charles Hermite once said about Abel: "Abel has left mathematicians enough to keep them busy for five hundred years." Another French mathematician, Adrien-Marie Legendre, said: "What a head the young Norwegian has!"

Today, the Abel Prize in mathematics is named in his honor. It's a very important award, like the Nobel Prize for math.

Contents

Life of Niels Henrik Abel

Early Years and Family

Niels Henrik Abel was born in Nedstrand, Norway, on August 5, 1802. He was the second child of Søren Georg Abel, a pastor, and Anne Marie Simonsen. His family lived in a rectory (a pastor's home) on Finnøy island.

Niels's father, Søren Georg Abel, had studied theology and philosophy. His grandfather, Hans Mathias Abel, was also a pastor. The Abel family came to Norway from Schleswig in the 1600s.

Niels's mother, Anne Marie Simonsen, came from a wealthy family in Risør. She enjoyed hosting parties. It seems she didn't focus much on raising her children. Niels and his brothers were taught at home by their father using handwritten books.

School and University Studies

In 1814, Norway became independent, and Niels's father, Søren Abel, was elected to the Storting (the Norwegian Parliament). This led Søren to send his son Niels to the Cathedral School in Christiania (now Oslo) in 1815. Niels was 13 years old. His older brother, Hans, joined him a year later.

In 1818, a new math teacher, Bernt Michael Holmboe, joined the school. He quickly saw Niels Henrik's amazing talent in mathematics. Holmboe encouraged Niels to study advanced math and even gave him private lessons after school.

Sadly, Niels's father faced some public difficulties and died in 1820 when Niels was 18. Bernt Michael Holmboe helped Niels Henrik Abel get a scholarship to stay in school. He also raised money from friends so Niels could study at the Royal Frederick University.

When Abel started university in 1821, he was already the most knowledgeable mathematician in Norway. He had read all the latest math books in the university library. At this time, Abel began working on the quintic equation. Mathematicians had been trying to solve this problem for over 250 years.

In 1821, Abel thought he had found the solution. His professors couldn't find any mistakes. They sent his work to Carl Ferdinand Degen, a leading mathematician in Copenhagen. Degen was impressed by Abel's sharp mind but doubted that such a long-standing problem could be solved by a young student. He asked Abel for a numerical example. While trying to create the example, Abel found a mistake in his own paper. This led him to a huge discovery in 1823: he proved that it was actually impossible to solve a fifth-degree equation (or higher) using simple algebraic methods.

Abel graduated in 1822. He was outstanding in mathematics but just average in other subjects.

Early Career and Travels

After graduating, university professors helped Abel financially. Professor Christopher Hansteen even let Abel live in his attic. Abel helped his younger brother and sister during this time.

In 1823, Abel published his first article in "Magazin for Naturvidenskaberne," Norway's first science journal. He published several more articles there. He also wrote a paper in French about how to solve certain math problems, but this work was lost while being reviewed and was never found again.

In mid-1823, Professor Rasmussen gave Abel money to travel to Copenhagen to meet other mathematicians. In Copenhagen, Abel met Christine Kemp, who would become his fiancée. They got engaged at Christmas 1824.

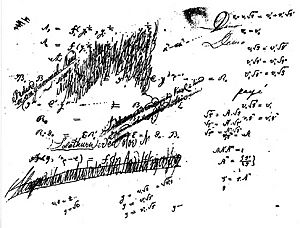

After returning to Norway, Abel applied for a scholarship to visit top mathematicians in Germany and France. He received some money to study German and French for two years. He was promised more money later for travel. During this time, in 1824, he published his most famous work: Mémoire sur les équations algébriques où on démontre l'impossibilité de la résolution de l'équation générale du cinquième degré (Memoir on algebraic equations, in which the impossibility of solving the general equation of the fifth degree is proven). This paper proved that the quintic equation cannot be solved by simple algebra. This is now known as the Abel–Ruffini theorem. The paper was very short to save printing costs. A more detailed proof was published in 1826 in Crelle's Journal.

In 1825, Abel received permission and a scholarship to travel abroad. In September 1825, he left Norway with four friends who were studying geology. Abel planned to visit Carl Friedrich Gauss in Göttingen and then go to Paris.

However, he changed his plans and went to Berlin with his friends. He spent four months there and became good friends with August Leopold Crelle. Crelle was starting a new math journal, Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik, and Abel helped him a lot. Abel wrote seven articles for the journal in its first year.

From Berlin, Abel traveled to the Alps with his friends. He visited Leipzig and Freiberg, where he researched different types of math functions, including elliptic, hyperelliptic, and a new group now called abelian functions.

In July 1826, Abel traveled alone to Paris. He had sent most of his work to Berlin for Crelle's Journal. But he saved what he thought was his most important work for the French Academy of Sciences. This was a theorem about adding algebraic differentials. He finished it in October 1826 and submitted it. However, his work was not well-known in Paris, and the theorem was put aside and forgotten until after his death.

Abel's money ran out, so he had to leave Paris in January 1827. He returned to Berlin and was offered a job as an editor for Crelle's Journal, but he decided not to take it. By May 1827, he was back in Norway. His trip abroad was seen as a failure by some because he hadn't visited Gauss and hadn't published anything in Paris. His scholarship was not renewed, and he had to take out a loan. He also started tutoring students. He continued to send most of his work to Crelle's Journal. In 1828, he published an important work on elliptic functions.

Abel's Final Days

While in Paris, Abel became sick with tuberculosis. At Christmas 1828, he traveled to Froland, Norway, to visit his fiancée. He became very ill during the journey. Although he felt a little better for the holidays, he died soon after, on April 6, 1829. This was just two days before a letter arrived from August Crelle, telling Abel that he had secured him a job as a professor at the University of Berlin.

Abel's Math Contributions

Abel proved that there is no general way to solve equations of the fifth degree (or higher) using only basic algebraic operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and roots. To do this, he helped create a new area of math called group theory. This field is now very important in many parts of mathematics and physics.

When he was just 16, Abel gave a strong proof of the binomial theorem, which works for all numbers. This was a big step forward from earlier work by Leonhard Euler. Abel also wrote important work on elliptic integrals, which laid the groundwork for the theory of elliptic functions.

While traveling, he published a paper showing the "double periodicity" of elliptic functions. Another mathematician, Adrien-Marie Legendre, called this paper "a monument more lasting than bronze." This means it was a very important and lasting achievement.

Abel also did research on abelian functions, which are a new class of functions he discovered.

Abel's Legacy

Many things in mathematics are named after Niels Henrik Abel. The word "abelian" is used often in math, like in "abelian group" or "abelian variety". It's even spelled with a small "a" because it's so common.

After Abel's death, his works were collected and published by the Norwegian government. His ideas helped clear up many confusing parts of math and opened up new areas of study.

On April 6, 1929, Norway issued four stamps to celebrate 100 years since Abel's death. His picture was also on a 500-kroner banknote. In 2002, four more stamps were issued for his 200th birthday, and Norway also made a 20-kroner coin in his honor.

There is a statue of Abel in Oslo, Norway. A crater on the Moon is also named Abel after him. In 2002, the Abel Prize was created to honor his memory and contributions to mathematics.

Images for kids

-

Statue of Niels Henrik Abel, called the "Abelmonumentet", in Oslo (former Christiania) by Gustav Vigeland.

-

Abelmonumentet in front of the Royal Palace, Oslo

See also

In Spanish: Niels Henrik Abel para niños

In Spanish: Niels Henrik Abel para niños

- List of things named after Niels Henrik Abel

- Évariste Galois

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |