Operation Alberich facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||||

New front line after Operation Alberich |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Operation Alberich | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front | |

| Type | Strategic withdrawal |

| Location | Noyon and Bapaume salients |

| Planned | 1916–1917 |

| Planned by | Field Marshal Rupprecht von Bayern |

| Commanded by | Quartermaster-General Erich Ludendorff |

| Objective | Retirement to the Hindenburg Line |

| Date | 9 February 1917 – 20 March 1917 |

| Executed by | Army Group Rupprecht of Bavaria (Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht von Bayern) |

| Outcome | Success |

Operation Alberich (known in German as Unternehmen Alberich) was a secret plan by the German military during the First World War. It involved a planned retreat from parts of the Western Front in France.

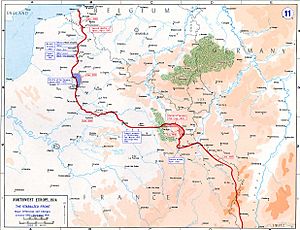

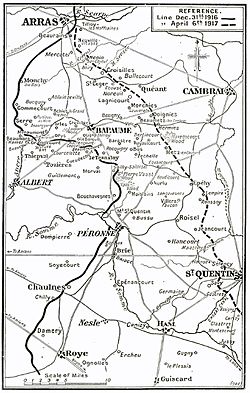

During the Battle of the Somme in 1916, the battle lines had formed two "salients." A salient is a part of the battle line that sticks out into enemy territory. These salients were near the towns of Arras, Saint-Quentin, and Noyon. Operation Alberich was a plan for the German army to pull back to a shorter, stronger defensive line called the Hindenburg Line (or Siegfriedstellung).

General Erich Ludendorff, a top German commander, was not sure about this retreat at first. However, the withdrawal happened between February 9 and March 20, 1917. This move shortened the German front line by about 40 kilometers (25 miles). By shortening their line, the Germans needed fewer soldiers to defend it. This freed up 13 to 14 army divisions (large groups of soldiers) to be used as a "strategic reserve." These extra troops were then ready to defend against a big attack planned by the French and British, known as the Nivelle Offensive.

Contents

Why the Germans Retreated

Winter 1916–1917 Challenges

In late 1916, Paul von Hindenburg and his deputy, Erich Ludendorff, took charge of the German army. They ordered the building of a new strong defensive line, the Hindenburg Line, east of the Somme battlefield. Ludendorff worried that retreating might lower the spirits of German soldiers and civilians.

The German army considered attacking instead, but they realized they didn't have enough soldiers for a major offensive. Even with more troops from the Eastern Front, the German army in the west had 154 divisions, while the Allies had 190 divisions, many of which were larger. This shortage of manpower made the retreat necessary. Moving to the Hindenburg Line would shorten the front by 40 to 45 kilometers (25 to 28 miles) and save 13 to 14 divisions.

German Discussions About Retreat

German military leaders debated the idea of retreating to the Hindenburg Line during the winter of 1916–1917. At first, it was seen as a last resort if the fighting on the Somme became too intense. After some successes and a quiet period in France, some German leaders felt the retreat might not be needed. However, a French attack at Verdun in December 1916 changed their minds.

By January 1917, Germany decided to restart unrestricted submarine warfare. They hoped this would force Britain out of the war. To win in the west, the German armies just needed to avoid defeat. Retreating to the Hindenburg Line would give them a strong defensive advantage.

The Hindenburg Line was built very well, with deep defenses, lots of barbed wire, and many machine-gun nests. This meant fewer divisions could hold a wider area. Before the British and French could attack these new defenses, they would have to rebuild roads and railways that the Germans planned to destroy.

The Germans planned to devastate the land they left behind. They would demolish villages, blow up bridges, dig up roads and railways, poison wells, and move the local people away. This "scorched earth" tactic would force the Allies to spend a lot of time and effort rebuilding before they could attack again. Every day the Allied attack was delayed gave the German U-boat campaign more time to work.

Not all German commanders agreed with the retreat. General Fritz von Below, commander of the German 1st Army, worried it would hurt the morale of his soldiers who had fought hard to defend the Somme front. However, other commanders reported that morale was low and defenses were in bad shape. For example, positions near the Ancre river were just flooded shell holes.

Because of these concerns, the Kaiser, Wilhelm II, ordered the land to be destroyed and the retreat to begin on February 9. The commanders who had opposed the retreat were overruled.

Preparing for the Retreat

Crown Prince Rupprecht's Concerns

Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria, who commanded a large group of German armies, wanted to retreat even further back to strongholds like Lille and Cambrai. However, the German high command decided this was not possible due to a lack of soldiers.

Rupprecht also disagreed with the plan to turn the Noyon Salient into a wasteland. He worried about the damage to Germany's reputation and the effect on his soldiers' discipline. The demolitions destroyed about 1,500 square kilometers (580 square miles) of land. Rupprecht even thought about resigning, but he decided against it to avoid showing a disagreement between Bavaria and the rest of Germany.

Fighting on the Ancre River

From January to March 1917, the British Fifth Army attacked German positions in the Ancre river valley. These attacks happened before the main German withdrawal. British attacks took advantage of tired German troops in weak defensive positions. Some German soldiers had low morale and were willing to surrender.

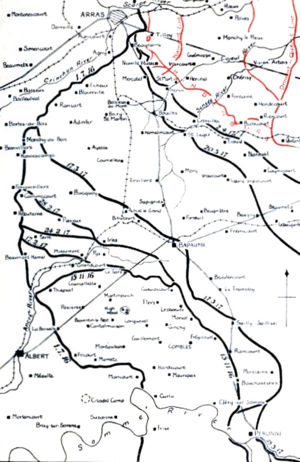

On February 22, the German 1st Army pulled back about 3 kilometers (2 miles) on a 15-kilometer (9.3-mile) front. This retreat surprised the British, even though they had intercepted some German radio messages. A second German withdrawal happened on March 11. The British didn't notice it until the next night. British patrols found the German positions empty in some areas.

Operation Alberich in Action

The German Withdrawal

Operation Alberich officially began on February 9, 1917. In the areas the Germans were leaving, they carried out their "scorched earth" plan. They dug up railways and roads, cut down trees, polluted water wells, destroyed towns and villages, and planted many land mines and booby traps.

About 125,000 healthy French civilians in the area were forced to move to work elsewhere in occupied France. Children, mothers, and the elderly were left behind with very little food.

On March 4, a French general, Louis Franchet d'Espèrey, suggested a big attack while the Germans were retreating. However, Robert Nivelle, the French Commander-in-Chief, only approved a small attack. This meant a chance to turn the German withdrawal into a full retreat was missed. The main German withdrawal happened from March 16 to 20. The Germans gave up about 40 kilometers (25 miles) of French territory. This was more land than the Allies had gained since September 1914.

British Follow-Up Operations

As the Germans pulled back, the British Third Army and Fifth Army followed them. During this time, the British captured Bapaume on March 17 and occupied Péronne on March 18.

Aftermath

The retreat to the Hindenburg Line was a success for the Germans. It shortened their front line and allowed them to save soldiers. This made their defenses stronger for the upcoming Allied attacks.

Images for kids

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |