Operation Sandblast facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Operation Sandblast |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War (1953–1962) | |

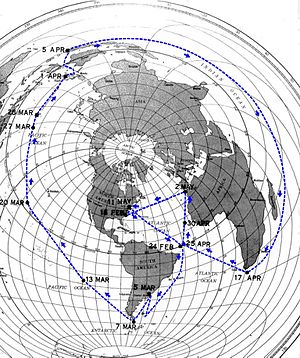

Triton's navigational track and mission milestones

|

|

| Type | Nuclear submarine operation |

| Location | World-wide |

| Planned by | United States Navy |

| Commanded by | Capt. Edward Beach, Jr. |

| Objective | First submerged circumnavigation |

| Date | 24 February 1960 – 25 April 1960 |

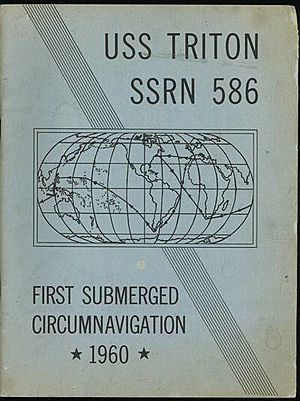

| Executed by | USS Triton (SSRN-586) |

| Outcome | Successfully completed mission |

Operation Sandblast was the secret name for an amazing journey. It was the first time a submarine traveled all the way around the world underwater. The United States Navy's nuclear-powered submarine, USS Triton (SSRN-586), completed this incredible feat in 1960. Captain Edward L. Beach Jr. was in charge of the submarine.

The journey lasted from February 24 to April 25, 1960. Triton traveled about 26,723 nautical miles (49,491 km) in 60 days and 21 hours. The trip started and ended at the St. Peter and Paul Rocks in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. During the voyage, Triton crossed the equator four times. It traveled at an average speed of 18 knots (33 km/h).

Triton's path around the world was similar to the first-ever circumnavigation by Ferdinand Magellan's expedition. That famous journey happened from 1519 to 1522.

Operation Sandblast was important for several reasons. It showed off American technology and science during the Cold War. This was a time of tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. The mission also proved that U.S. Navy nuclear submarines could travel long distances underwater without any help. This was a big step for future submarines that would carry missiles. The mission also collected lots of scientific information about the ocean.

After the voyage, there were fewer big celebrations than planned. This was because a U.S. spy plane was shot down over the Soviet Union. This event, called the 1960 U-2 incident, caused a lot of trouble. However, Triton and its crew still received special awards for their success.

Contents

The Idea Behind the Mission

Why Triton Went Around the World

The idea for a submarine to travel around the world underwater was discussed for a while. Captain Evan P. Aurand, who worked for President Dwight D. Eisenhower, thought it would be a great way to show American strength. He called the idea "Project Magellan." He believed it would boost America's image before an important meeting with the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev.

Admiral Arleigh Burke, a top Navy officer, agreed it was possible. He estimated the trip could take between 56 and 75 days. President Eisenhower approved the mission. The USS Triton (SSRN-586) was chosen for this special task.

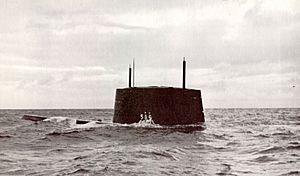

Triton (pictured) was the biggest and most powerful submarine built at that time. It cost $109 million. It was also special because it had two nuclear reactors, which made it very fast. During tests, Triton reached speeds of over 30 knots (56 km/h).

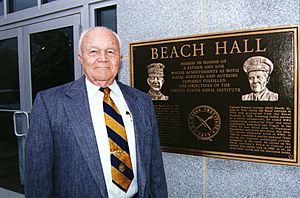

Captain Edward L. Beach, Jr. (pictured) was Triton's first commanding officer. He was a very experienced submarine officer. He had fought in World War II and received many awards. He also wrote popular books about submarines. Captain Beach felt that Triton was a unique ship and needed to do something special.

Triton was based in New London, Connecticut. Before the mission, special communication equipment was installed. The crew had to prepare quickly for the secret journey.

What the Mission Hoped to Achieve

On February 4, 1960, Captain Beach learned the true plan. Triton's upcoming trip was a secret mission called Operation Sandblast. It would be a submerged trip around the world. The main goals were:

- To study the ocean and its depths.

- To see how the crew handled living underwater for a long time. This was important for future missile submarines.

- To show that U.S. nuclear submarines could operate far from home without being detected.

The Navy chose the name "Sandblast" because it would take "a lot of sand" (courage) for the crew to succeed. Captain Beach's personal code name during the mission was "Sand."

Getting Ready for the Big Trip

Captain Beach told his officers about the secret mission. They had only 12 days to get everything ready. Most of the crew didn't know the real plan at first. They were told the submarine was going to the Caribbean Sea for more tests. The crew also had to take care of their personal business before leaving.

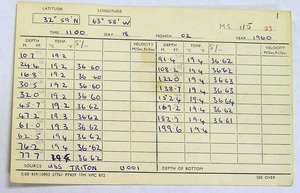

The officers carefully planned the exact route for the journey. The supply officer made sure there was enough food for a 120-day trip (pictured). They loaded about 77,613 pounds (35,205 kg) of food, including frozen items, canned meat, coffee, and potatoes.

Special scientists and experts joined the crew. A photographer from National Geographic magazine was on board to take pictures. A psychologist studied how the crew handled being isolated for so long. Other scientists collected data about the ocean, gravity, and navigation.

On February 15, 1960, Triton did a final check of all its equipment. Everything was ready for the historic voyage.

The Journey Around the World Underwater

Starting the Adventure

Triton left New London on February 16, 1960 (pictured). The next day, Captain Beach told the crew the real mission (pictured): "We’re going around the world, nonstop. And we’re going to do it entirely submerged."

Captain Beach decided to lead with a "light touch." He knew the crew's excitement was high. He wanted to save pressure for real emergencies. The crew followed a weekly routine with drills, classes, and maintenance.

Every night, Triton would come close to the surface to check its position and refresh the air inside. This was important because the submarine didn't have a way to make its own oxygen from seawater.

Early in the trip, Triton had a few small problems, like a leak and a false alarm about radiation. These were quickly fixed. On February 23, Triton found an uncharted underwater mountain.

One of the biggest challenges was keeping the ship clean and getting rid of trash. Triton had a special garbage disposal unit. If it broke, they had to use the torpedo tubes, which was not ideal.

On February 24, Triton reached the St. Peter and Paul Rocks (pictured). This was the starting point for the underwater circumnavigation. Later that day, Triton crossed the equator for the first time. The crew celebrated with a traditional "crossing the line" ceremony.

Heading Towards Cape Horn

On March 1, 1960, Triton faced three problems. A crew member, John R. Poole, suffered from kidney stones. The ship's depth-measuring device (fathometer) stopped working. This made it harder to avoid hitting underwater mountains. Also, one of the reactors showed a malfunction.

Luckily, the crew fixed the fathometer and the reactor. Poole's condition was serious. Captain Beach decided to take a risk and surface Triton to transfer him to another ship. This was the only time Triton surfaced during the circumnavigation. Poole was transferred to the USS Macon off Montevideo, Uruguay. He was the only crew member who didn't finish the voyage.

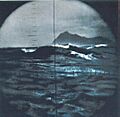

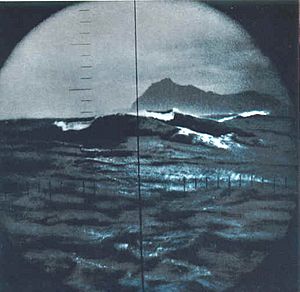

After the transfer, Triton dove back down and continued south. On March 7, it rounded Cape Horn (pictured), the southern tip of South America. Captain Beach described it as "bold and forbidding." He let all the crew see it through the periscope.

Across the Vast Pacific Ocean

On March 7, Triton entered the Pacific Ocean. It would not see land for a long time. On March 8, the submarine found another uncharted underwater mountain. It also practiced an emergency shutdown of both its reactors.

Two days later, a leak appeared in the engine room. The crew quickly made a temporary fix. On March 12, the fathometer broke again. Since it was outside the submarine, it couldn't be fixed. The crew found a clever way to use other systems to detect underwater objects.

Triton spotted Easter Island on March 13. The crew took photos and everyone got a chance to see it through the periscope. The next visual landmark would be Guam, thousands of miles away.

On March 17, a broken air compressor was repaired. The crew showed great skill in fixing it, even making new parts from scratch. Captain Beach was very impressed by their ingenuity.

On March 19, Triton found another underwater peak and crossed the equator for the second time. The next day, the crew celebrated with a luau (a Hawaiian party) as they passed near Pearl Harbor.

On March 23, Triton crossed the International Date Line, losing a day from its calendar. On March 27, a memorial service was held for the submarine's namesake, which was lost in World War II. Three water slugs were fired from the torpedo tubes as a salute.

On March 28, Triton reached Guam. Petty Officer Edward Carbullido (pictured), who was born on Guam, was able to see his parents' house through the periscope. Triton then headed for the Philippines, the halfway point of its journey.

Through the Philippines

On March 31, Triton traveled through the Philippine Trench and the many islands of the Philippines. A special water sample was taken in the Surigao Strait for a retired admiral.

On April 1, Triton spotted Mactan Island and the monument (pictured) to Ferdinand Magellan. This marked the halfway point of the circumnavigation.

Later that day, on April Fools' Day, a young Filipino man in a small canoe (pictured) saw Triton's periscope. He was the only unauthorized person to spot the submarine during its secret voyage. The National Geographic photographer took pictures of this unexpected meeting. The fisherman, Rufino Baring, thought he had seen a sea monster!

On April 2, Triton's navigation systems had problems, but the crew quickly fixed them. The submarine then left Philippine waters and entered the Indian Ocean on April 5.

Across the Indian Ocean

Entering the Indian Ocean was dramatic. The change in seawater density made Triton dive suddenly. Captain Beach said he had never experienced such a big change before.

While crossing the Indian Ocean, Triton conducted a "sealed-ship experiment." From April 10, the submarine stayed completely sealed, without refreshing the air from outside. They used compressed air and "oxygen candles" to keep the air breathable. Also, from April 15, smoking was not allowed on the ship.

A psychologist studied the crew during this time. He wanted to see how not smoking affected them. He found that smokers became irritable and had trouble sleeping. This experiment helped the Navy understand how long missions affect sailors.

On Easter Sunday, April 17, Triton sighted the Cape of Good Hope and entered the Atlantic Ocean again.

The Final Stretch Home

The smoking ban ended on April 18. Captain Beach walked through the ship smoking a cigar to show the ban was lifted. On April 20, Triton crossed the Prime Meridian.

On April 24, a hydraulic line burst in the torpedo room. A quick-thinking crew member, Allen W. Steele, stopped a potentially serious problem. He received an award for his actions.

On April 25, Triton crossed the equator one last time. Soon after, it sighted the St. Peter and Paul Rocks again, completing the first submerged circumnavigation of the world!

Back Home

Triton then headed for Cadiz, Spain, to honor Magellan's starting point. It met the destroyer John W. Weeks there on May 2, 1960. Triton briefly surfaced (pictured) to transfer a special plaque.

Triton returned to the United States, surfacing off Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, on May 10, 1960 (pictured). Captain Beach was flown by helicopter to Washington, D.C. President Eisenhower announced Triton's amazing achievement to the world. Triton arrived back in Groton, Connecticut, on May 11, 1960.

What Triton Achieved

Triton's journey was very important for the United States. It showed the world America's advanced technology. It also proved how long and far nuclear submarines could travel underwater. The mission collected a lot of valuable information about the oceans.

Key Facts About the Voyage

Here are the main details of Triton's historic trip:

- Distance: 26,723 nautical miles (49,491 km)

- Dates: February 24 to April 25, 1960

- Time: 60 days and 21 hours

- Average Speed: 18 knots (33 km/h)

Triton crossed the equator four times:

- February 24, 1960 – near St. Peter and Paul Rocks (Atlantic Ocean)

- March 19, 1960 – near Christmas Island (Pacific Ocean)

- April 3, 1960 – Makassar Strait (Indonesia)

- April 25, 1960 – near St. Peter and Paul Rocks (Atlantic Ocean)

The total time Triton was underwater during its entire shakedown cruise was 83 days, 9 hours. This covered a distance of 35,979.1 nautical miles (66,633.4 km).

Scientific and Security Successes

Operation Sandblast collected a lot of scientific data. Scientists gathered water samples to study ocean temperature, saltiness, and density. This information helps submarines operate better. The submarine also measured Earth's gravity field, which helps with navigation. Triton released 144 special bottles to track ocean currents. It also mapped uncharted underwater mountains and coral reefs. This data is still useful today for understanding ocean changes.

The mission also proved that nuclear submarines could operate for a very long time without outside help. Triton tested new navigation and communication systems. These systems were very important for the Navy's future missile submarines. The psychological tests on the crew also helped NASA prepare for its manned space program, Project Mercury. Engineers even said that getting to the moon was simpler than guiding a nuclear submarine around the world underwater!

After the Mission

News and Recognition

Because of the 1960 U-2 incident, many of the big celebrations for Triton's voyage were canceled. However, the mission still received a lot of attention from magazines and TV shows.

Captain Edward L. Beach appeared on TV news programs (pictured). The American government published a version of Triton's log book (pictured). Captain Beach also wrote articles and a book about the journey. He gave speeches at places like the National Press Club (pictured).

For its amazing achievement, Triton received the Presidential Unit Citation. This is a very high award for military units. It was only the second time a U.S. Navy ship received this award for a peacetime mission. All crew members who made the voyage were allowed to wear a special golden globe on their award ribbon (pictured).

Captain Beach received the Legion of Merit from President Eisenhower. He also received other awards, including a science degree and the "Magellan of the Deep" award.

In 2011, Operation Sandblast and Triton were featured in an exhibit at the U.S. Navy Museum in Washington, D.C.

Triton's Lasting Impact

The journey of Triton was a huge success. It showed that humans could live and work deep in the ocean for months. It also proved that nuclear power could drive a large vehicle around the world without needing to refuel. The mission showed how accurate navigation and control had become.

The Triton Plaque

Before leaving, Captain Beach asked for a special plaque to be made. It would honor both Triton's voyage and Magellan's first circumnavigation. The plaque (pictured) is a brass disk with a sailing ship and a submarine dolphin symbol. It has the words "AVE NOBILIS DUX, ITERUM FACTUM EST," which means "Hail Noble Captain, It Is Done Again."

This plaque was given to the Spanish government. It is now on display in Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Spain, where Magellan's journey began. Copies of the plaque are also in museums and Navy locations in the United States.

Memorials to Triton

There are several memorials to Triton and its historic voyage.

- Triton Light: A lighthouse at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It has a globe filled with water samples from the 22 seas Triton passed through.

- Beach Hall: The headquarters for the United States Naval Institute is named after Captain Edward L. Beach, Jr. (pictured) and his father. Triton's dive wheel is on display there.

- Submarine Hall of Fame: Triton was added to the Submarine Hall of Fame in 2003.

- USS Triton Submarine Memorial Park: Located in Richland, Washington, this park features Triton's sail superstructure (pictured). It's a place to remember the submarine and its history.

50th Anniversary Celebrations

The 50th anniversary of Operation Sandblast was celebrated on April 10, 2010. Events included a large Navy ball (pictured) and activities at the U.S. Navy Submarine Force Library and Museum.

Former crew members received special souvenirs. The University of Texas Marine Science Institute also created a radio program about the mission.

Many articles and a new biography of Captain Beach were published for the anniversary. Captain James C. Hay, who served on Triton, said the voyage "proved the crew's mettle" and showed that the U.S. Navy "could go anywhere, at anytime, and do what ever was required."

Images for kids

-

Cape Horn (March 7, 1960)

See also

In Spanish: Operación Sandblast para niños

In Spanish: Operación Sandblast para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |