Patrice Lumumba facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Patrice Lumumba

|

|

|---|---|

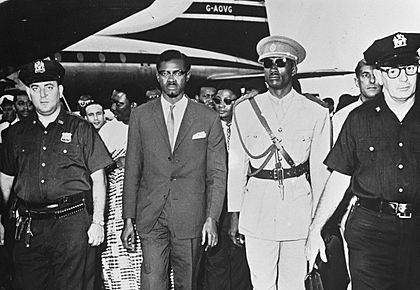

Lumumba in 1960

|

|

| 1st Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo | |

| In office 24 June – 5 September 1960 |

|

| President | Joseph Kasa-Vubu |

| Deputy | Antoine Gizenga |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Iléo |

| 1st Minister of National Defense | |

| In office 24 June 1960 – 5 September 1960 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Ferdinand Kazadi |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Élias Okit'Asombo

2 July 1925 Katakokombe, Congo-Kasaï, Belgian Congo |

| Died | 17 January 1961 (aged 35) near Élisabethville, State of Katanga |

| Cause of death | Execution (by firing squad) |

| Political party | MNC |

| Spouse |

Pauline Opango

(m. 1951) |

| Children |

|

Patrice Émery Lumumba (2 July 1925 – 17 January 1961) was an important leader in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He helped his country gain independence from Belgium. From June to September 1960, he was the first prime minister of the Republic of the Congo.

Lumumba led the Congolese National Movement (MNC) party from 1958 until he died in 1961. He believed strongly in African nationalism, which meant that African countries should be free and united. He played a big part in changing the Congo from a Belgian colony into an independent nation.

Soon after the Congo became independent in June 1960, problems started. Soldiers in the army began to rebel. This led to a big conflict called the Congo Crisis. Lumumba asked the United States and the United Nations for help. He wanted them to stop a group of people in the Katanga region who wanted to break away from the Congo. These people were supported by Belgium.

However, the United States and the United Nations did not help. They worried that Lumumba might be secretly supporting communism. These worries grew when Lumumba asked the Soviet Union for help. This made the situation worse with President Joseph Kasa-Vubu and army chief Mobutu Sese Seko. The United States and Belgium were against the Soviet Union during the Cold War, so they also opposed Lumumba.

After Mobutu took control of the army, Lumumba tried to escape. He wanted to join his supporters in Stanleyville, who had formed their own government. But Lumumba was caught and put in prison by Mobutu's forces. He was then given to the authorities in Katanga and was killed there. Belgian and Katangan officials were present. His body was buried in a shallow grave, but later dug up and destroyed.

After his death, many people saw Lumumba as a hero for the wider African unity movement. Over the years, investigations have shown more about how Lumumba died. They also showed the roles that Belgium and the United States played. In 2002, Belgium officially said sorry for its part in his death. In 2022, a gold-capped tooth, which was all that remained of his body, was returned to the Democratic Republic of the Congo by Belgium.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Early Career and Interests

- Becoming a Political Leader

- Congo's Independence and Lumumba's Election

- Prime Minister in a Time of Crisis

- Lumumba's Dismissal

- Final Days and Death

- Foreign Involvement in His Death

- Lumumba's Political Ideas

- Lumumba's Legacy

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Education

Patrice Lumumba was born on 2 July 1925. His parents were Julienne Wamato Lomendja and François Tolenga Otetshima, a farmer. He was born in Onalua, in the Katakokombe region of the Belgian Congo. He was a member of the Tetela ethnic group. His birth name was Élias Okit'Asombo.

Lumumba had three brothers and one half-brother. He grew up in a Catholic family. He went to a Protestant primary school and a Catholic missionary school. He also attended a government post office training school, where he did very well. He was known for being a smart and outspoken young man. He often pointed out mistakes made by his teachers. This bold way of speaking would become a key part of his life.

Lumumba could speak several languages. These included Tetela, French, Lingala, Swahili, and Tshiluba.

Early Career and Interests

Outside of school, Lumumba was interested in ideas from the Age of Enlightenment. These were ideas about freedom and human rights from thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire. He also liked writers such as Molière and Victor Hugo. Lumumba wrote poems, and many of them spoke out against colonial rule.

He worked as a traveling beer salesman. Later, he became a postal clerk in Stanleyville for eleven years. In 1951, he married Pauline Opangu. After World War II, many young leaders in Africa started working for their countries' independence from colonial powers.

In 1952, Lumumba worked as an assistant for a French researcher studying Stanleyville. That same year, he helped start an alumni group for students of Scheut schools. He became its president, even though he had not attended one of these schools himself. In 1955, Lumumba became a leader for the Cercles of Stanleyville. He also joined the Liberal Party of Belgium. He wrote and shared party materials.

After a trip to Belgium in 1956, he faced some legal trouble. He was arrested for a money issue at the post office. He was found guilty and sentenced to prison for 12 months.

Becoming a Political Leader

After he was released from prison, Lumumba helped create the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC) party. This happened on 5 October 1958. He quickly became the party's leader. The MNC was different from other parties in Congo at that time. It did not focus on just one ethnic group. Instead, it wanted independence for the whole country. It also supported gradual African leadership in government. The party wanted the government to lead economic growth and stay neutral in foreign affairs.

Lumumba was very popular. He was a great speaker and had strong ideas. This gave him more freedom in politics than other leaders who relied on Belgian connections. In December 1958, Lumumba represented the MNC at a big meeting in Accra, Ghana. This was the All-African Peoples' Conference, hosted by Ghana's president, Kwame Nkrumah. At this meeting, Lumumba's belief in Pan-Africanism (unity of all African peoples) grew stronger. Nkrumah was very impressed by Lumumba's intelligence.

In late October 1959, Lumumba was arrested again. He was accused of causing a protest against colonial rule in Stanleyville, where 30 people died. He was sentenced to six months in prison. His trial was set to begin on 18 January 1960. This was the same day the Congolese Round Table Conference started in Brussels. This conference was meant to plan the future of the Congo. Even though Lumumba was in prison, the MNC won many votes in the local elections in December. Because of strong pressure from other leaders at the conference, Lumumba was released. He was then allowed to attend the Brussels conference.

Congo's Independence and Lumumba's Election

The conference ended on 27 January 1960. It declared that the Congo would become independent. The date was set for 30 June 1960. National elections were held from 11 to 25 May 1960. Lumumba's MNC party won the most votes.

Six weeks before independence, a Belgian minister was sent to Congo. He was to advise King Baudouin on choosing a leader to form the new government. Lumumba was chosen first to try and form a government that included many different groups. However, he found it hard to get everyone to agree.

Another leader, Joseph Kasa-Vubu, was then asked to form a government. But he also struggled to get support. Most party leaders did not want a government that did not include Lumumba. On 21 June 1960, the parliament met. A member of Lumumba's party was elected as president of the Chamber. This showed that Lumumba's group had strong support.

With time running out before independence, King Baudouin finally appointed Lumumba to form the government.

Once it was clear that Lumumba's group controlled parliament, other politicians wanted to join his government. By 22 June 1960, Lumumba had a list for his government. He continued talks with other leaders, including Kasa-Vubu. Kasa-Vubu eventually agreed to join Lumumba's government.

The new government, led by Lumumba, was very diverse. Its members came from different backgrounds and had different political ideas. On 23 June 1960, the Chamber of Deputies voted on Lumumba's government. Lumumba gave a speech, promising to keep the country united. He also said he would follow a neutral foreign policy. Most members liked his speech.

After a long debate, the Chamber voted. 74 members voted for the government, 5 against, and 1 abstained. The next day, the Senate also voted. 60 voted for the government, 12 against, and 8 abstained. With these votes, Lumumba's government was officially approved.

When he became prime minister, Lumumba had two main goals. First, he wanted independence to truly improve life for the Congolese people. Second, he wanted to unite the country as one strong state. He aimed to get rid of divisions based on tribes or regions.

To achieve his first goal, Lumumba wanted to put Africans in charge of the government. This was called "Africanisation." The Belgians did not like this idea. They thought it would cause problems and make many Belgian workers leave. Lumumba was upset that the Belgians did not help him with this. He worried that independence would not feel "real" to ordinary Congolese people.

For his second goal, Lumumba was inspired by Ghana's President Kwame Nkrumah. He wanted to combine his party, the MNC, with its allies. He hoped to form one big national party. He wanted this party to unite the country and bring all people together.

Independence Day was celebrated on 30 June 1960. Many important people, including King Baudouin of Belgium, attended. King Baudouin gave a speech praising Belgium's colonial rule. He mentioned his great-granduncle, Leopold II, which ignored the terrible things that happened during his rule.

Lumumba then gave his own speech. He spoke about the suffering of the Congolese people under Belgian rule. He also spoke about the need for true freedom. Many European journalists were shocked by his strong words. Western media criticized his speech. They worried it would cause more conflict and chaos in the Congo.

Prime Minister in a Time of Crisis

Early Days of Independence

The first few days after independence were a national holiday. People celebrated peacefully. Lumumba's office was very busy. Many people, both Congolese and European, came to help him. Lumumba spent most of his time at official events. On 3 July, he announced that all prisoners would be released, but this did not happen.

The next day, he met with his ministers. They discussed problems among the soldiers of the Force Publique (the army). Many soldiers expected quick promotions and more money after independence. They were disappointed that changes were slow. They felt that the new government leaders were getting rich, but the soldiers' lives were not improving.

The government decided to create committees to improve the administration, justice system, and army. They also wanted to end racial discrimination. Parliament met and voted to greatly increase their own salaries. Lumumba was one of the few who disagreed. He called it a "wasteful idea."

The Congo Crisis Begins

On 5 July 1960, General Émile Janssens, the army commander, told his troops to stay disciplined. But that evening, soldiers protested. Janssens called for backup, but those soldiers also rebelled. This was the start of the Congo Crisis. It became the main challenge for Lumumba's government.

The next day, Lumumba fired Janssens. He promoted all Congolese soldiers by one rank. But the rebellions spread. Even though the problems were in specific areas, it seemed like the whole country was in chaos. News reports said that Europeans were leaving the country. Lumumba spoke on the radio, promising quick and big changes. He said the country would look different in a few months.

Despite the government's efforts, the rebellions continued. Lumumba and President Kasa-Vubu personally stepped in to calm soldiers in some areas.

On 8 July, Lumumba renamed the army the "Armée Nationale Congolaise" (ANC). He put Africans in charge. He made Sergeant Major Victor Lundula the general and commander. He chose Joseph Mobutu as colonel and chief of staff. These choices were made even though Lundula was not very experienced. There were also rumors about Mobutu's connections to Belgian and US intelligence. All European officers in the army were replaced by Africans.

By the next day, the rebellions had spread across the country. Some Europeans were killed. Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu traveled to promote peace. Belgium sent 6,000 troops to the Congo on 10 July. They said it was to protect their citizens. Most Europeans went to Katanga Province, which had many natural resources.

Lumumba was angry, but he agreed to the Belgian action. He said they must only protect their citizens and follow Congolese orders. The same day, the Belgian Navy attacked Matadi, killing Congolese civilians. This made tensions much worse. Belgian forces then moved into cities, including the capital.

On 11 July, the State of Katanga declared itself independent. Its leader was Moïse Tshombe. Belgium and mining companies supported Katanga. Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu protested Belgium's actions to the United Nations. They asked for Belgian troops to leave and for UN peacekeepers to come. The United Nations Security Council passed a resolution. It called for Belgian forces to leave and for the United Nations Operation in the Congo (ONUC) to be set up.

Even with UN troops, problems continued. Lumumba asked UN troops to stop the rebellion in Katanga. But the UN forces were not allowed to do this. On 14 July, Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu ended diplomatic ties with Belgium. Frustrated with Western countries, they asked the Soviet Union for help.

Trip to the United States

Lumumba decided to go to New York City. He wanted to explain his government's situation to the United Nations himself. Before he left, he announced an economic agreement with a US businessman. He also said that Soviet help was "no longer necessary." He planned to ask the United States for technical help.

On 22 July, Lumumba left the Congo for New York City. He met with UN officials to discuss the withdrawal of Belgian troops and technical assistance. African diplomats encouraged Lumumba to wait before making more big economic deals. Lumumba met with UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld for three days. Their talks went well. Lumumba said his government would stay "neutral."

On 27 July, Lumumba went to Washington, D.C. He met with the US Secretary of State. He asked for financial and technical help. The US government said they would only give aid through the UN. Lumumba felt the UN was not doing enough to remove Belgian troops or stop the Katanga rebels. On 29 July, he went to Canada to ask for help. Canada also said they would only give aid through the UN.

Frustrated, Lumumba met with the Soviet ambassador in Canada. They talked about military equipment. When he returned to New York, his attitude towards the UN was less friendly. The US government also became more negative. They heard reports of violence by Congolese soldiers. Belgium was also upset that Lumumba had been welcomed in Washington. The Belgian government saw Lumumba as communist and anti-Western. Many other Western governments believed this view.

Lumumba was frustrated with the UN's slow action in Katanga. He decided to delay his return to the Congo. He visited several African countries. He wanted to pressure Hammarskjöld. If that failed, he wanted to get military support to stop Katanga. From 2 to 8 August, Lumumba visited Tunisia, Morocco, Guinea, Ghana, Liberia, and Togoland. He was welcomed in each country. Guinea and Ghana promised military support. The others wanted to work through the UN.

In Ghana, Lumumba signed a secret agreement with President Nkrumah. They planned a "Union of African States." It would be a federation with a republican government. They agreed to hold a meeting of African states in Léopoldville in August. Lumumba returned to the Congo. He felt confident he could now get military help from African countries. He also thought he could get technical aid directly from African nations. This disagreed with Hammarskjöld's goal of sending all support through the UN. Lumumba and some ministers were wary of the UN option. They felt UN workers would not directly follow their orders.

Efforts to Regain Control

On 9 August, Lumumba declared a state of emergency in the Congo. He then issued several orders to show his power. One order made it illegal to form groups without government permission. Another said the government could ban publications that made the administration look bad. The government also shut down some news agencies. Lumumba nationalized local Belgian news offices. He created the Agence Congolaise de Presse. He wanted to stop biased reporting and share the government's message more easily.

Another order required public gatherings to be approved six days in advance. On 16 August, Lumumba announced special military rule for six months. During August, Lumumba started to work less with his full cabinet. He consulted more with trusted officials and ministers. Lumumba's office was disorganized. His chief of staff was often absent and was spying for the Belgian government. Lumumba constantly received rumors, which made him very suspicious of others.

Lumumba ordered Congolese troops to stop the rebellion in South Kasai. This region had important rail links needed for a campaign in Katanga. The operation was successful. But the conflict soon turned into violence between ethnic groups. The army was involved in killing Luba civilians. People in South Kasai blamed Lumumba for the army's actions.

President Kasa-Vubu publicly said that only a federalist government could bring peace. This weakened his alliance with Lumumba. It also shifted political support away from Lumumba's idea of a single, unified state. Ethnic tensions against Lumumba grew. The Catholic Church, which was still powerful, openly criticized his government.

Even with South Kasai under control, the Congo was not strong enough to retake Katanga. Lumumba called for an African conference in Leopoldville. But no foreign leaders came, and no country promised military support. Lumumba again demanded that UN peacekeepers help stop the revolt. He threatened to bring in Soviet troops if they refused. The UN then denied Lumumba the use of its forces. The possibility of direct Soviet involvement seemed more likely.

Lumumba's Dismissal

Kasa-Vubu's Order

President Kasa-Vubu began to fear that Lumumba would try to take over the government. On the evening of 5 September, Kasa-Vubu announced on the radio that he had fired Lumumba. He also fired six of Lumumba's ministers. He said this was because of the killings in South Kasai and for involving the Soviets.

When Lumumba heard this, he went to the national radio station. UN guards were there. Even though they were told to stop him, they let him in. Lumumba spoke on the radio, saying his dismissal was illegal. He called Kasa-Vubu a traitor and said he was no longer president. Kasa-Vubu's action was not legal because he did not have the approval of other ministers. Lumumba pointed this out in a letter to Hammarskjöld and on the radio.

Later that day, Kasa-Vubu got two ministers to sign his dismissal order. He then announced Lumumba's dismissal again on Brazzaville radio.

Lumumba and his loyal ministers ordered the arrest of the two ministers who signed the order. One of them, Albert Delvaux, was arrested. The Chamber of Deputies met to discuss the situation. Delvaux appeared and spoke against his arrest. Lumumba then gave his speech. He did not directly attack Kasa-Vubu. Instead, he blamed other politicians for using the presidency to hide their actions. He said Kasa-Vubu had never criticized the government before.

The Chamber voted to cancel both Kasa-Vubu's and Lumumba's dismissal orders. The next day, Lumumba gave a similar speech to the Senate. The Senate then voted to support his government. This meant that Lumumba's government was still officially in power.

However, there was no clear way to solve the legal disagreement. Many African diplomats and the new head of ONUC tried to get Kasa-Vubu and Lumumba to work together. But they failed. On 13 September, Parliament met and voted to give Lumumba emergency powers.

Mobutu's Takeover

On 14 September, Mobutu announced on the radio that he was taking control. He called it a "peaceful revolution." He said he was stopping the power of the President, Lumumba's government, and Parliament until 31 December. He stated that experts would run the government. He also said that all Soviet Bloc countries should close their embassies.

Lumumba was surprised by this takeover. He went to Mobutu to try and change his mind. He stayed the night there. But in the morning, he was attacked by soldiers who blamed him for the killings in South Kasai. UN peacekeepers helped him escape. However, his briefcase was left behind. Some of his political opponents found it. They published documents they claimed were inside. These included letters from Nkrumah and requests for help from the Soviet Union and China. Some of these papers were real, but others were likely fake.

Despite the takeover, African diplomats still tried to get Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu to reconcile. But Kasa-Vubu refused. He wanted to bring Katanga back into the Congo through talks. Tshombe, Katanga's leader, said he would not talk to any government that included Lumumba, whom he called a "communist."

Mobutu announced that he would hold a meeting to discuss the Congo's future. But Lumumba continued to act as if he was still prime minister from his home. He held meetings and made public statements. He even went out in the capital, saying he was still in charge.

Mobutu became frustrated with Lumumba. He faced strong political pressure. By the end of September, Mobutu was no longer trying to reconcile them. He sided with Kasa-Vubu. He ordered army units to surround Lumumba's home. But UN peacekeepers formed a barrier, stopping them from arresting him. Lumumba was confined to his home.

On 24 November, the UN voted to recognize Mobutu's new representatives. This ignored Lumumba's original choices. Lumumba decided to join his Deputy Prime Minister, Antoine Gizenga, in Stanleyville. He planned to lead a campaign to regain power. On 27 November, he left the capital with his wife, Pauline, and his youngest child.

Instead of rushing to the border, Lumumba stopped in villages and talked to people. On 1 December, Mobutu's troops caught up with him. Lumumba and his advisors had crossed a river, but his wife and child were caught on the other side. Fearing for their safety, Lumumba went back. His advisors warned him not to, saying they might never see him again. Mobutu's men arrested him. He was taken to Ilebo and then flown back to Léopoldville. Mobutu said Lumumba would be tried for causing rebellion in the army.

Final Days and Death

On 3 December 1960, Lumumba was sent to Thysville military barracks. He was with Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito, two political friends. They were treated poorly by the guards. In his last known letter, Lumumba wrote that they were living in "impossible conditions."

On 13 January 1961, the soldiers at Camp Hardy became restless. They refused to work unless they were paid. Some wanted Lumumba released, while others thought he was dangerous. Kasa-Vubu, Mobutu, and other officials came to the camp. They talked with the troops. Conflict was avoided, but it was clear that keeping Lumumba there was too risky.

The last Belgian Minister of the Colonies ordered that Lumumba, Mpolo, and Okito be taken to the State of Katanga.

Lumumba was forced onto a plane to Elisabethville on 17 January 1961. When they arrived, he and his friends were taken to a house.

Later that night, Lumumba was driven to an isolated place. A Belgian investigation found that Katanga's authorities carried out the execution. It reported that Katanga president Tshombe and two other ministers were present. Four Belgian officers were also there, following Katangan orders. The execution is believed to have happened on 17 January 1961, between 9:40 PM and 9:43 PM.

Announcement of Death

No official statement was made for three weeks, even though rumors spread that Lumumba was dead. On 18 January, a Katangan official was one of the first to reveal Lumumba's death. He told people at a bar that Lumumba had been murdered.

On 10 February, the radio announced that Lumumba and two other prisoners had escaped. His death was officially announced on Katangan radio on 13 February. They claimed he was killed by angry villagers after escaping from prison.

After Lumumba's death was announced, protests happened in several European countries. In Belgrade, protesters attacked the Belgian embassy. In London, people marched to the Belgian embassy. In New York City, a protest at the United Nations Security Council turned violent.

Foreign Involvement in His Death

Lumumba was killed by a firing squad led by a Belgian mercenary. A Belgian police commissioner from Katanga was in charge of the execution site. The Katangan government, which wanted to break away, was strongly supported by the Belgian mining company Union Minière du Haut-Katanga.

On 18 January, the execution team became worried. They heard that people had seen the burial of the three bodies. So, they dug up the remains and moved them to another place near the border.

Return of His Remains

On 30 June 2020, Lumumba's daughter, Juliana Lumumba, wrote a letter to King Philippe of Belgium. She asked for "the relics of Patrice Émery Lumumba to be returned to the ground of his ancestors." She called her father "a hero without a grave." On 10 September 2020, a Belgian judge ruled that Lumumba's remains must be returned to his family.

In May 2021, Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi announced that Lumumba's last remains would be returned. However, the ceremony was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

On 20 June 2022, Lumumba's children received their father's remains. This happened at a ceremony in Brussels. The Belgian Prime Minister, Alexander De Croo, apologized on behalf of the Belgian government. He said sorry for his country's role in Lumumba's death. Later, a coffin with his remains was shown to the public. It was covered with the Congolese flag. People from Congo and other African countries living in Belgium paid their respects.

Lumumba's final resting place will be in a special memorial in Kinshasa. The Democratic Republic of the Congo declared three days of national mourning. The burial will happen on the 61st anniversary of his famous independence speech. Belgian prosecutors are still investigating his murder as a "war crime."

Lumumba's Political Ideas

Lumumba did not have a detailed political or economic plan. But he was the first Congolese leader to speak about the Congo's history in a way that was different from Belgium's view of colonization. He highlighted the suffering of the local people under European rule.

Lumumba was unique among leaders of his time. He included all Congolese people in his vision. Other leaders often focused only on their own ethnic groups or regions. He believed in humanism, which means valuing egalitarianism (equality), social justice, liberty (freedom), and basic human rights. He thought the government should actively work for the good of the people. He believed government action was needed to ensure equality, justice, and harmony in Congolese society.

Lumumba's Legacy

Historical View

Stories about Lumumba's life and death were published soon after he died. Many books about him came out starting in 1961. Lumumba's role in the Congo's independence movement is well known. He is usually seen as its most important leader. His achievements are often celebrated as his own work, not just part of a larger movement.

Political Impact

Because he was in government for a short time and died in a controversial way, people still debate Lumumba's political impact. His downfall hurt African nationalist movements. He is mostly remembered for his assassination. Many American historians say his death helped make the American civil rights movement more radical in the 1960s. Many African-American activist groups used his death to express their ideas.

People often remember Lumumba as a symbol, rather than focusing on his political ideas. In the Congo, he is mainly a symbol of national unity. Outside the Congo, he is often seen as a leader for African unity and someone who fought against colonial rule.

Seen as a Martyr

The way Lumumba died has led many to see him as a martyr. A martyr is someone who dies for a cause.

In the Congo, people believe Lumumba was killed because he wanted the Congo to be self-governing. They see his death as a result of Western interference.

Honoring Lumumba

In 1961, Adoula became Prime Minister of the Congo. He visited Stanleyville and placed flowers at a memorial for Lumumba. Later, when Tshombe became Prime Minister in 1964, he did the same. On 30 June 1966, Mobutu honored Lumumba. He called him a "national hero." A special place was made at the Brouwez House, where Lumumba was held before his death. Mobutu also planned other ways to remember Lumumba. One was a banknote with Lumumba's face, which was released the next year. This was the only banknote during Mobutu's rule that showed a leader other than himself.

In later years, Mobutu's government spoke less about Lumumba. They were suspicious of unofficial tributes to him. After Laurent-Désiré Kabila took power in the 1990s, new Congolese money was printed with Lumumba's image.

In January 2003, Joseph Kabila, the new president, unveiled a statue of Lumumba. In Guinea, Lumumba was featured on a coin and banknotes. This was unusual because he had no national ties to Guinea. It is rare for a country to put a foreigner's image on its regular money. As of 2020, Lumumba has been on 16 different postage stamps. Many streets and public squares around the world are named after him. The Peoples' Friendship University of the USSR was renamed "Patrice Lumumba Peoples' Friendship University" in 1961. It was renamed again in 1992.

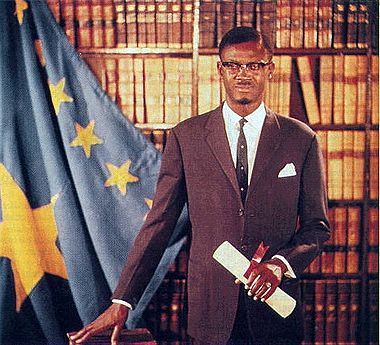

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Patrice Lumumba para niños

In Spanish: Patrice Lumumba para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |