Mobutu Sese Seko facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mobutu Sese Seko

|

|

|---|---|

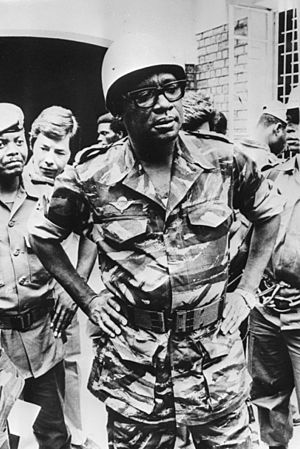

Mobutu in 1983

|

|

| President of Zaire | |

| In office 27 October 1971 – 16 May 1997 |

|

| Preceded by | Post established |

| Succeeded by | Post abolished Laurent-Désiré Kabila (as President of the re-established DRC) |

| President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| In office 24 November 1965 – 27 October 1971 |

|

| Preceded by | Joseph Kasa-Vubu |

| Succeeded by | Post abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Joseph-Désiré Mobutu

14 October 1930 Lisala, Équateur, Belgian Congo |

| Died | 7 September 1997 (aged 66) Rabat, Rabat-Salé-Kénitra, Morocco |

| Nationality | Congolese |

| Political party | Popular Movement of the Revolution |

| Spouses |

Marie-Antoinette Gbiatibwa Gogbe Yetene

(m. 1955; Bobi Ladawa

(m. 1980–1997) |

| Children | 21 (including Kongulu and Nzanga) |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service | 1949–1997 |

| Rank | Field Marshal (Army) Admiral (Navy) Commander in Chief (Military) |

| Battles/wars | Congo Crisis Shaba invasions First Congo War |

Mobutu Sese Seko (born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997) was a military officer and politician from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He served as the president of Zaire from 1965 to 1997. Before 1971, the country was known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Mobutu first came to power during the Congo Crisis. He was the Chief of Staff of the Army. With support from Belgium and the United States, he removed the elected government of Patrice Lumumba in 1960. Mobutu then helped set up a government that led to Lumumba's death in 1961. He continued to lead the army until he took full control in 1965.

To make his power stronger, Mobutu created the Popular Movement of the Revolution in 1967. This became the only legal political party. He changed the country's name to Zaire in 1971 and his own name to Mobutu Sese Seko in 1972. He wanted to remove all colonial cultural influence through a program called "national authenticity". Mobutu became a very powerful leader, and his image was promoted everywhere.

During his time in power, Mobutu became very rich. He was known for taking a lot of money from the country's resources. This led some people to call his rule a "kleptocracy", meaning a government where leaders steal from the country. There were also many human rights problems. The country faced high inflation, a large debt, and its money lost a lot of value.

Mobutu received strong support from the United States, France, and Belgium. These countries saw him as a strong opponent of communism in Africa. He also had good relationships with apartheid South Africa, Israel, and the Greek junta. Later, Mao Zedong of China also supported him. This was mainly because Mobutu was against the Soviet Union. China's financial help gave Mobutu more freedom in dealing with Western countries.

By 1990, the economy was getting worse, and there was unrest. Mobutu was forced to work with his political opponents. However, he used his army to stop changes. In May 1997, rebel forces led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila took over the country. Mobutu was forced to leave and go into exile. He was already sick with prostate cancer and died three months later in Morocco.

Contents

Mobutu's Early Life and Education

Mobutu was born in 1930 in Lisala, which was then part of the Belgian Congo. He belonged to the Ngbandi ethnic group. His mother, Marie Madeleine Yemo, worked as a hotel maid. She met and married Albéric Gbemani, a cook for a Belgian judge. Mobutu was born shortly after.

Mobutu's father died when he was eight years old. After that, his uncle and grandfather raised him. The Belgian judge's wife liked Mobutu and taught him to speak, read, and write French very well. French was the official language during the colonial period.

His mother moved often with her four children, relying on relatives for help. Mobutu started his schooling in Léopoldville (now Kinshasa). Later, his mother sent him to an uncle in Coquilhatville (present-day Mbandaka). There, he attended a Catholic boarding school. Mobutu was tall and strong, excelling in sports. He was also good at school subjects and ran the class newspaper. He was known for his jokes and playful nature.

In 1949, Mobutu secretly traveled by boat to Léopoldville. He was found by the priests a few weeks later. As a punishment for rebellious students, he was ordered to serve seven years in the colonial army, called the Force Publique (FP).

Army Service and Early Journalism

Mobutu found discipline in the army. He also found a father figure in Sergeant Louis Bobozo. Mobutu continued his studies by borrowing European newspapers and books. He read them whenever he had free time. He especially liked the writings of Charles de Gaulle, Winston Churchill, and Niccolò Machiavelli. After taking an accounting course, Mobutu started writing as a journalist.

As a soldier, Mobutu wrote about politics for Actualités Africaines (African News). This was a magazine started by a Belgian colonial. In 1956, he left the army to become a full-time journalist for the Léopoldville newspaper L'Avenir.

Two years later, he went to Belgium to cover the 1958 World Exposition. He stayed there to get more training in journalism. During this time, Mobutu met many young Congolese thinkers who wanted to end colonial rule. He became friends with Patrice Lumumba and joined Lumumba's Congolese National Movement (MNC). Mobutu eventually became Lumumba's personal assistant. Some people believe Belgian intelligence recruited Mobutu to be an informer.

Mobutu's Rise to Power

After the general election, Patrice Lumumba was asked to form a government. He made Mobutu the Secretary of State to the Presidency. Mobutu had a lot of influence in deciding who would be in the rest of the government.

The Congo Crisis and First Coup

On 5 July 1960, soldiers of the Force Publique in Léopoldville rebelled. They were unhappy with their white leaders and working conditions. The revolt quickly spread. Mobutu helped officials talk with the soldiers to free the officers and their families. On 8 July, the government met to discuss putting African leaders in charge of the army.

Mobutu was given the role of Army Chief of Staff and promoted to colonel. A British diplomat, Brian Urquhart, who worked with the United Nations, met Mobutu in July 1960. He described Mobutu as a "sensible young man" who seemed to care about his country.

Violence broke out in the south, with groups wanting to break away. The Belgian government encouraged this to keep access to rich mines. Lumumba asked the Soviet Union for help because the United Nations forces were not stopping the rebels. The Soviets sent military aid and advisers. This was during the Cold War, and the US feared the spread of communism. So, the US and Belgium encouraged President Joseph Kasa-Vubu to remove Lumumba. Kasa-Vubu did so on 5 September. Lumumba then tried to remove Kasa-Vubu.

Both Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu ordered Mobutu to arrest the other. Mobutu was under a lot of pressure from Western countries and his own officers to get rid of the Soviet presence. On 14 September, Mobutu took power in a peaceful coup. He announced that both Kasa-Vubu and Lumumba were "neutralized." He set up a new government of university graduates. Lumumba was forced to stay at his home, where UN peacekeepers protected him from Mobutu's soldiers.

Lumumba later tried to escape to join his supporters, but Mobutu's troops captured him in December. Mobutu still saw him as a threat. On 17 January 1961, Lumumba was sent to the rebelling State of Katanga. It was later found that he was killed that same day by the rebel forces.

On 23 January 1961, Kasa-Vubu promoted Mobutu to major-general. This was done to make the army stronger and Mobutu's position more secure. In 1964, Pierre Mulele led another rebellion, taking over two-thirds of the Congo. Mobutu's army fought back and took back all the territory by 1965.

Second Coup and Stronger Power

In March 1965, Prime Minister Moise Tshombe's party won many votes. But Kasa-Vubu chose another leader, Évariste Kimba, as prime minister. Parliament refused to approve Kimba twice. With the government almost stopped, Mobutu took power in a peaceful coup on 24 November. He was 35 years old.

Mobutu took almost complete control for five years. He told a large crowd that politicians had ruined the Congo in five years. He said it would take him at least that long to fix things. So, he announced there would be no more political parties for five years. In November 1965, Parliament gave most of its law-making powers to Mobutu. In March 1966, he took away their right to review his decisions. Two weeks later, his government permanently closed Parliament.

At first, Mobutu's government said it was not political. The word "politician" became linked to being bad or corrupt. In 1966, a group called the Corps of Volunteers of the Republic was formed. It was meant to get people to support Mobutu. He was called the nation's "Second National Hero" after Lumumba. Mobutu tried to present himself as carrying on Lumumba's ideas. One of his main goals was "authentic Congolese nationalism." In 1966, Mobutu started changing European city names to African ones. Léopoldville became Kinshasa, Stanleyville became Kisangani, and Élisabethville became Lubumbashi.

In 1967, the Popular Movement of the Revolution (MPR) was created. Until 1990, it was the only legal political party. The MPR's ideas included nationalism, revolution, and "authenticity." They said their revolution was "neither capitalism nor communism." One of their slogans was "Neither left nor right." Later, they added "nor even center."

All trade unions were combined into one union, the National Union of Zairian Workers. This union was controlled by the government. Mobutu wanted the union to support his policies, not act independently. Independent trade unions were illegal until 1991.

Mobutu faced many challenges early on. He made many opponents join him by giving them special favors. Those he could not convince, he dealt with strongly. In 1966, four government ministers were arrested. They were accused of planning a coup. They were tried by a military court and publicly executed in front of over 50,000 people. Mobutu said this was to show that he was in charge.

Rebellions by former soldiers were crushed. So were the Stanleyville mutinies of 1967 led by white soldiers for hire. By 1970, most threats to his power were gone. Law and order were brought to most parts of the country. This year was the peak of Mobutu's power.

In 1970, King Baudouin of Belgium visited Kinshasa. That same year, presidential and parliamentary elections were held. The MPR was the only party allowed to choose candidates. Mobutu was the only candidate for president. Voting was not secret. Voters chose a green paper if they supported Mobutu, and a red paper if they did not. A green ballot was seen as a vote for hope, while a red ballot was seen as a vote for chaos. Mobutu won with almost all the votes, according to official numbers. The legislative elections were held in a similar way.

As he gained more power, Mobutu created several military forces just to protect himself. These included the Special Presidential Division, Civil Guard, and military intelligence.

Authenticity Campaign and New Identity

Mobutu started a campaign called authenticité, which promoted African culture. He began renaming cities with colonial names on 1 June 1966. Léopoldville became Kinshasa, Elisabethville became Lubumbashi, and Stanleyville became Kisangani. In October 1971, he renamed the country the Republic of Zaire.

He ordered people to change their European names to African ones. Priests were warned they could go to prison if they baptized a Zairian child with a European name. Western clothes and ties were banned. Men had to wear a Mao-style tunic called an abacost. Christmas was moved from December to June.

In 1972, Mobutu changed his own name to Mobutu Sese Seko Nkuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga. This means "The all-powerful warrior who, because of his endurance and inflexible will to win, goes from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake." Around this time, he stopped wearing his military uniform. He started wearing his famous look: a tall man with a walking stick, an abacost, thick glasses, and a leopard-skin toque.

In 1974, a new constitution made Mobutu's control even stronger. It said the MPR was the "single institution" in the country. All citizens automatically became members of the MPR from birth. The constitution stated that the MPR was led by its president, who was elected every seven years. This party president was also automatically the only candidate for president of the republic. He was confirmed by a public vote. This system gave Mobutu almost all power. He was reelected three times with very high percentages of votes.

Mobutu's Rule and Economy

Early in his rule, Mobutu made his power stronger by publicly executing political rivals. These included former Prime Minister Évariste Kimba and three other ministers in May 1966. They were accused of planning a coup. Mobutu said these executions were to show that he was in charge.

In 1968, Pierre Mulele, a rebel leader, was tricked into returning from exile. He was promised safety but was killed by Mobutu's forces instead.

Mobutu later changed his approach. He started buying off political rivals. He would give them high positions or money to gain their loyalty. He often moved government members around, changing who held which job. This was to make sure no one became too powerful to threaten him. Between 1965 and 1997, Mobutu changed his government 60 times. This constant reshuffling made ministers feel insecure. They knew they could be removed at any time. This encouraged them to steal as much as possible while they were in power.

Another tactic was to arrest and sometimes torture government members who disagreed with him. Later, he would pardon them and give them high positions. A historian wrote that Mobutu created a system where corruption was rewarded. By 1970, it was thought that Mobutu had stolen 60% of the national budget that year. This made him one of the most corrupt leaders in Africa.

In 1972, Mobutu tried to have himself named president for life, but this did not happen. In June 1983, he promoted himself to the rank of Field Marshal.

To get money from Congo's resources, Mobutu first took over foreign-owned companies. He forced European investors out. But he often gave these companies to his relatives and friends. They quickly stole the companies' money. In 1973–1974, Mobutu started his "Zairianization" campaign. This meant taking foreign-owned businesses and giving them to Zairians.

In 1974, the price of copper, Zaire's most important export, dropped by 50%. This was a disaster for Zaire's economy. The country went from being prosperous to almost bankrupt. Zaire had to ask the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for help with its debts. The IMF found a lot of corruption in Zaire's finances.

Mobutu looked for other support. He visited China in 1974 and came back wearing a Mao jacket. He also started saying he wanted to make the "Zairian revolution" more radical. The businesses he had just given to Zairians were then taken over by the state. At the same time, Mobutu cut state employees' salaries by 50%.

By 1977, Mobutu's policies had caused such a bad economic situation that he had to try to get foreign investors back. Rebels from Katanga, based in Angola, invaded Zaire that year. France sent 1,500 Moroccan paratroopers to help. They pushed back the rebels, ending Shaba I. The rebels attacked Zaire again in 1978 in the Shaba II invasion. Belgium and France sent troops with US support and defeated the rebels again.

Mobutu was re-elected in single-candidate elections in 1977 and 1984. He spent most of his time increasing his personal wealth. By 1984, it was estimated he had about US$5 billion. Most of this money was kept in Swiss banks. This amount was almost equal to the country's foreign debt at the time. In a speech in 1976, Mobutu openly accepted small corruption. He said: "If you want to steal, steal a little in a nice way, but if you steal too much to become rich overnight, you will be caught." By 1989, the government could not pay back its international loans from Belgium.

Mobutu owned many Mercedes-Benz cars to travel between his palaces. Meanwhile, the country's roads fell apart, and many public workers were not paid for months. Most of the money was taken by Mobutu, his family, and top leaders. Only his bodyguards, the Special Presidential Division, were paid well. A common saying was that "the civil servants pretended to work while the state pretended to pay them." The army also suffered from low morale and often robbed civilians.

Another problem was very high inflation. The quick drop in the value of salaries encouraged corruption among public servants.

Mobutu was known for his luxurious lifestyle. He had a yacht called Kamanyola. In Gbadolite, he built a palace, called the "Versailles of the jungle." For shopping trips to Paris, he would rent a Concorde airplane from Air France. He had the Gbadolite Airport built with a runway long enough for the Concorde.

Mobutu's rule became known as one of the world's best examples of a "kleptocracy" and nepotism. Close relatives and members of his Ngbandi tribe were given high positions in the military and government. He wanted his oldest son, Nyiwa, to become president after him. However, Nyiwa died in 1994.

Mobutu led one of the longest dictatorships in Africa. He became very rich by selling his nation's natural resources. Meanwhile, his people lived in poverty. He created a totalitarian regime that was responsible for many human rights violations. He tried to remove all Belgian cultural influences from the country. He also remained against communism to get support from other countries.

Mobutu was the focus of a very strong personality cult. The evening news often started with his image appearing from clouds, like a god. His pictures were hung in many public places. Government officials wore pins with his picture. He was given titles like "Father of the Nation," "Messiah," "Guide of the Revolution," and "Savior of the People." In 1975, the media was even forbidden to use anyone else's name.

Mobutu used the tensions of the Cold War to his advantage. He gained a lot of support from Western countries and organizations like the International Monetary Fund.

International Relations

Relations with Belgium

Zaire's relationship with Belgium changed often. Sometimes they were very close, and sometimes they were openly hostile. Belgian leaders often did not react strongly when Mobutu acted against Belgium's interests. This was partly because Belgian politics were very divided.

Relations became difficult early in Mobutu's rule over disagreements about Belgian businesses in the country. But they soon improved. Mobutu and his family were guests of the Belgian king in 1968. A cooperation agreement was signed that year. During King Baudouin's visit to Kinshasa in 1970, a friendship treaty was signed. However, Mobutu ended the treaty in 1974. This was because Belgium refused to ban a book written against him. Mobutu's "Zairianisation" policy also caused problems. This policy took over foreign-owned businesses and gave them to Zairians.

Relations with France

Zaire was important to France because it was the second most populated French-speaking country at the time. During the early years, France supported the more conservative groups in Congo. After the Katangan rebellion was stopped, Zaire signed a cooperation treaty with France.

Under French President Charles de Gaulle, relations between the two countries grew stronger. They shared many interests. In 1971, Finance Minister Valéry Giscard d'Estaing visited Zaire. Later, as France's president, he became very close to Mobutu. France became one of Mobutu's closest allies. During the Shaba invasions, France strongly supported Mobutu. In the first invasion, France sent 1,500 Moroccan troops to Zaire. A year later, in the second invasion, France (along with Belgium) sent its own paratroopers to help Mobutu.

Relations with China

At first, Zaire's relationship with China was not good. Mobutu remembered that China had helped rebels in the past. He also did not want China to have a seat at the United Nations. However, by 1972, he started to see China differently. He saw them as a way to balance his close ties with the United States, Israel, and South Africa. In November 1972, Mobutu officially recognized China.

The next year, Mobutu visited Beijing. He met with Chairman Mao Zedong and was promised $100 million in aid. In 1974, Mobutu made a surprise visit to China and North Korea. When he returned, his policies became more radical. He started criticizing Belgium and the United States. He also introduced a program called salongo, which was forced civic work. Mobutu even used a title – the Helmsman – from Mao.

China and Zaire both wanted to stop the Soviet Union from gaining power in Africa. They secretly sent aid to groups fighting against Soviet-backed forces in Angola. China sent weapons and money to these rebels. Zaire also tried to invade Angola to set up a friendly government, but Cuban troops pushed them back. China sent military aid to Zaire during the Shaba invasions and accused the Soviet Union and Cuba of trying to destabilize central Africa.

Relations with the Soviet Union

Mobutu's relationship with the Soviet Union was cold. He was strongly against communism. The USSR had supported Patrice Lumumba and the Simba rebellion. However, to appear neutral, Mobutu renewed ties in 1967. The first Soviet ambassador arrived in 1968. Mobutu joined the United States in criticizing the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia that year.

Mobutu saw the Soviet presence as useful for two reasons. It helped him appear neutral, and it gave him someone to blame for problems at home. For example, in 1970, he expelled four Soviet diplomats for "subversive activities." In 1971, twenty Soviet officials were expelled for supposedly causing student protests.

Moscow was the only major world capital Mobutu never visited. He canceled a planned visit in 1974 and went to China and North Korea instead. Relations became even colder in 1975 when they were on opposite sides in the Angolan Civil War. This made Zaire's foreign policy change. Mobutu turned more to the US and its allies.

Relations with the United States

Zaire generally had good relations with the United States. The US was the third largest donor of aid to Zaire. Mobutu became friends with several US presidents, including Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush.

Relations became difficult in 1974–1975. Mobutu's speeches became more radical, and he criticized American foreign policy. In 1975, Mobutu accused the Central Intelligence Agency of planning to overthrow him. He arrested several Zairian generals and civilians. However, many people doubted these claims. Some thought Mobutu made up the plot to remove talented officers who might threaten him. Despite these problems, the relationship quickly improved when both countries supported the same side in the Angolan Civil War.

The Carter Administration kept some distance from Mobutu due to his poor human rights record. Still, Zaire received almost half of the foreign aid Carter sent to Africa. During the first Shaba invasion, the US only sent non-military supplies. But in the second Shaba invasion, the US played a more active role. It provided transport and support to French and Belgian paratroopers who helped Mobutu.

Mobutu had a very good relationship with the Reagan Administration. During Reagan's presidency, Mobutu visited the White House three times. Criticism of Zaire's human rights record by the US was largely silenced. In 1983, Reagan praised Mobutu as "a voice of good sense and goodwill."

Mobutu also had a friendly relationship with Reagan's successor, George H. W. Bush. He was the first African head of state to visit Bush at the White House. However, Mobutu's relationship with the US changed greatly after the end of the Cold War. With the Soviet Union gone, there was no longer a reason to support Mobutu as a defense against communism. So, the US and other Western powers began to pressure Mobutu to make his government more democratic. Mobutu sadly said: "I am the latest victim of the cold war, no longer needed by the US. The lesson is that my support for American policy counts for nothing." In 1993, the US government refused Mobutu a visa to visit Washington, D.C.

Mobutu's Downfall

In May 1990, the Cold War ended, and the international political situation changed. Along with economic problems and unrest at home, Mobutu agreed to end his party's monopoly on power. In May 1990, students protested against Mobutu's rule. On the night of 11 May 1990, a special military unit attacked the campus. At least 290 students were killed. This massacre led the nations of Europe, the United States, and Canada to stop all non-humanitarian aid to Zaire. This marked the beginning of the end of Western support for Mobutu.

Mobutu appointed a temporary government to lead to promised elections. But he kept control of the security forces and important government departments. Divisions led to two governments in 1993: one supporting Mobutu and one against him.

The economy was still very bad. In 1994, the two groups merged. Mobutu appointed Kengo Wa Dondo as prime minister. Kengo supported strict economic policies. During this time, Mobutu became very sick. While he was in Europe for medical treatment, ethnic Tutsis took control of much of eastern Zaire.

Overthrow by Rebels

The events that led to Mobutu's fall began with the Rwandan Genocide in 1994. Hundreds of thousands of Hutus, including many who had committed genocide, fled into refugee camps in eastern Zaire. Mobutu welcomed these Hutu extremists. He allowed them to set up military bases in eastern Zaire. From these bases, they attacked Tutsis in Rwanda and Zaire. The new Rwandan government then sent military aid to the Zairian Tutsis. This conflict began to make eastern Zaire unstable.

In November 1996, Mobutu's government ordered Tutsis to leave Zaire or face death. The ethnic Tutsis in Zaire, called Banyamulenge, started a rebellion. From eastern Zaire, the rebels, helped by forces from Uganda and Rwanda, began to march toward Kinshasa. They joined forces with local groups who opposed Mobutu, led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila. Burundi and Angola also supported this growing rebellion, which became the First Congo War.

Mobutu was sick with cancer and in Switzerland for treatment. He could not organize resistance, and his army quickly fell apart. The rebel forces would have taken over the country even faster if the roads and infrastructure had not been so bad. In most areas, there were no paved roads, only dirt paths.

By mid-1997, Kabila's forces continued their advance. The remains of Mobutu's army offered almost no resistance. On 16 May 1997, after failed peace talks, Mobutu fled into exile. Kabila's forces, known as the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (AFDL), declared victory the next day. On 23 May 1997, Zaire was renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Exile and Death

Mobutu first went to Togo. But President Gnassingbé Eyadéma asked him to leave a few days later. From 23 May 1997, Mobutu lived mostly in Rabat, Morocco. He died there on 7 September 1997, from prostate cancer, at age 66. He is buried in an above-ground tomb in the Christian cemetery in Rabat.

In December 2007, the National Assembly of the Democratic Republic of the Congo suggested bringing his remains back to the DRC. However, this has not happened yet. Mobutu remains buried in Morocco.

Mobutu's Family

Mobutu was married twice. His first wife was Marie-Antoinette Gbiatibwa Gogbe Yetene. They married in 1955 and had nine children. She died in 1977. On 1 May 1980, he married his mistress, Bobi Ladawa. This happened just before a visit by Pope John Paul II, making their relationship official in the eyes of the Church.

Two of his sons from his first marriage died during his lifetime. Two more died after his death. His elder son from his second marriage, Nzanga Mobutu Ngbangawe, is now the head of the family. He was a candidate in the 2006 presidential elections. He later served as Minister of State for Agriculture. One of his daughters, Yakpwa, was briefly married to a Belgian man who wrote a book describing Mobutu's lavish lifestyle.

Mobutu had at least twenty-one children.

Mobutu's Legacy

According to his obituary in The New York Times, Mobutu stayed in power for a long time using three main methods: force, cleverness, and using state money to buy off enemies. His constant taking of money from the national treasury and major industries led to the term 'kleptocracy'. This term describes a government where officials are very corrupt. It is believed that he became one of the world's richest heads of state.

In 2011, Time magazine called him the "typical African dictator."

Mobutu was known for taking billions of US dollars from his country. Some estimates say he stole between US$4 billion and $15 billion. According to Pierre Janssen, his daughter's ex-husband, Mobutu did not care about the cost of the expensive gifts he gave to his friends. Janssen described Mobutu's daily life, which included several bottles of wine each day and lavish meals.

Transparency International estimates that Mobutu stole over US$5 billion from his country. This ranks him as one of the most corrupt leaders since 1984.

Mobutu played a key role in bringing the "Rumble in the Jungle" boxing match to Zaire. This famous fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman happened on 30 October 1974. The promoter, Don King, promised each fighter five million dollars. Mobutu agreed to pay the ten million dollars and host the fight. He wanted to gain international recognition and legitimacy for his country. Mobutu gained a lot of publicity for Zaire and its people. Ali reportedly said: "Some countries go to war to get their names out there, and wars cost a lot more than ten million (dollars)." Mobutu presented the rebuilt 20 May Stadium, a multi-million-dollar project built for the fight, to the people of Zaire.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Mobutu Sese Seko para niños

In Spanish: Mobutu Sese Seko para niños