Zaire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Republic of Zaire

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971–1997 | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

Motto: Paix — Justice — Travail

"Peace — Justice — Work" |

|||||||||

|

Anthem: La Zaïroise

"The Song of Zaire" |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Capital and largest city

|

Kinshasa 4°19′S 15°19′E / 4.317°S 15.317°E |

||||||||

| Official languages | French | ||||||||

| Recognised national languages | |||||||||

| Ethnic groups | See Ethnic groups section below | ||||||||

| Religion

(1986)

|

|

||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Zairian | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary Mobutist one-party presidential republic under a totalitarian military dictatorship | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1965–1997

|

Mobutu Sese Seko | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

|

• 1977–1979 (first)

|

Mpinga Kasenda | ||||||||

|

• 1997 (last)

|

Likulia Bolongo | ||||||||

| Legislature | Legislative Council | ||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||

|

• Coup d'état

|

24 November 1965 | ||||||||

|

• Established

|

27 October 1971 | ||||||||

|

• Constitution promulgated

|

15 August 1974 | ||||||||

|

• Mobutu overthrown

|

17 May 1997 | ||||||||

|

• Death of Mobutu

|

7 September 1997 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

|

• Total

|

2,345,409 km2 (905,567 sq mi) | ||||||||

|

• Water (%)

|

3.32 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

|

• 1971

|

18,400,000 | ||||||||

|

• 1997

|

46,498,539 | ||||||||

| GDP (nominal) | 1983 estimate | ||||||||

|

• Total

|

|||||||||

| HDI (1990 formula) | 0.294 low |

||||||||

| Currency | Zaïre (ZRN) | ||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+1 to +2 (WAT and CAT) | ||||||||

| Driving side | right | ||||||||

| Calling code | +243 | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | ZR | ||||||||

| Internet TLD | .zr | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | Democratic Republic of the Congo | ||||||||

Zaire, officially called the Republic of Zaire, was the name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1971 to 1997. This country is located in Central Africa. It was the third-largest country in Africa by size. It was also the 11th-largest country in the world during its time.

With over 23 million people, Zaire was the most populated country in Africa where French was spoken. Zaire was very important to Western countries during the Cold War. This was especially true for the U.S. It helped balance the influence of the Soviet Union in Africa. The U.S. and its friends supported the government of Mobutu Sese Seko (1965–1997). They gave money and military help to stop the spread of communism.

Zaire was a country ruled by one political party and a military leader. Mobutu Sese Seko and his party, the Popular Movement of the Revolution, were in charge. Zaire was formed after Mobutu took power in a military takeover in 1965. This happened after five years of political problems after the country became independent from Belgium. This time is sometimes called the Second Congolese Republic.

Mobutu also started a plan called Authenticité. This plan aimed to remove influences from the time when Belgium ruled the country. After the Cold War ended, Mobutu lost support from the U.S. He had to announce a new government in 1990 because people wanted changes. By the time Zaire fell, it was known for a lot of corruption and poor management of its money.

Zaire collapsed in the 1990s. This happened because of problems in the eastern parts of the country. These problems followed the Rwandan genocide and increasing violence between different ethnic groups. In 1996, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, a leader of the AFDL group, started a rebellion against Mobutu. As rebel forces moved west, Mobutu left the country. Kabila's forces then took control. In 1997, the country's name was changed back to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Mobutu died less than four months later while living in another country.

Contents

What's in a Name? The Story of Zaire

The country's name, Zaïre, came from the Congo River. The Portuguese sometimes called this river Zaire. This name came from the Kikongo words nzere o zadi. These words mean "river that swallows rivers." Over time, the name Congo slowly replaced Zaire in English. By the 1800s, Congo was the more common name.

A Look at Zaire's History

Mobutu Takes Control

In 1965, the country then known as Congo-Léopoldville had problems with power sharing. This caused instability. Mobutu Sese Seko took power again. This time, Mobutu became the president himself. From 1965, Mobutu was the main political leader. He changed how the country was run many times. He called himself the "Father of the Nation." On October 27, 1971, he announced the country would be renamed the Republic of Zaire.

As part of the Authenticité policy in the early 1970s, people in Zaire had to use "authentic" African names. They could no longer use European names. Mobutu changed his name from Joseph-Désiré to Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga. This long name roughly means "the all-conquering warrior, who goes from triumph to triumph."

Mobutu later said that the time before his rule was full of "chaos, disorder, and mistakes." His new government worked to rebuild and strengthen the country. They created a new political party to lead the state. This party was very important to Mobutu's plans.

Changes to the Government

By 1967, Mobutu had strong control. He gave the country a new set of laws and created one main political party. The new laws were approved by almost everyone in a vote in June 1967. These laws gave the president a lot of power. The president was the head of the country, the government, the army, and foreign policy.

The biggest change was the creation of the Popular Movement of the Revolution (MPR) on April 17, 1967. This party became the most important part of the country. The government was now seen as part of the party. In October 1967, the party and government jobs were combined. This meant the party's role spread to all parts of the government. It also included trade unions, youth groups, and student organizations.

Three years after changing the country's name to Zaire, Mobutu made new laws. These laws made his control over the country even stronger. Every five years, the MPR chose a president. This person was the only candidate for president of the country. People then voted to confirm him. Under this system, Mobutu was reelected in 1977 and 1984 with almost all votes saying "yes." The MPR was called the country's "only institution." Its president had "full power." All citizens of Zaire automatically became members of the MPR when they were born. This gave Mobutu, as president of the MPR, complete political control.

Expanding Control Over People

To make the idea of "the nation politically organized" real, the government took more control over people's lives. This meant that youth groups and worker organizations became part of the MPR. In July 1967, the party announced the creation of the Youth of the Popular Revolutionary Movement (JMPR). A month earlier, the National Union of Zairian Workers (UNTZA) was started. It brought together three existing worker groups.

The goal was to change trade unions from fighting for workers to supporting government plans. This would create a link between workers and the state. The JMPR was meant to connect students and the state. In reality, the government wanted to control groups that might oppose it. By giving important jobs to union and youth leaders, the government hoped to use their influence. However, many people noticed that this did not truly make people support the government.

The government continued to bring more groups under its control. Women's groups and the press were eventually controlled by the party. In December 1971, Mobutu also limited the power of churches. From then on, only three churches were recognized: the Church of Christ in Zaire, the Kimbanguist Church, and the Roman Catholic Church.

The government took control of the universities of Kinshasa and Kisangani. Mobutu also banned all Christian names and put JMPR groups in all religious schools. This caused problems between the Roman Catholic Church and the government. It was not until 1975, after pressure from the Vatican, that the government eased its attacks. It returned some control of schools to the church. Meanwhile, many unrecognized religious groups were shut down, and their leaders were jailed. This was based on a 1971 law that allowed the state to close any group that threatened public order.

Mobutu also made sure to stop any groups that used ethnic loyalties. He was against using ethnicity for political reasons. He banned groups like the Association of Lulua Brothers. This group was formed in 1953 to react to the growing influence of the rival Luba people. He also banned Liboke lya Bangala, a group formed to represent Lingala speakers. It helped Mobutu that his own ethnic background was not widely known. However, as people became unhappy, ethnic tensions started to appear again.

Power Becomes Centralized

At the same time, important changes were made to how the country was run in 1967 and 1973. These changes aimed to give more power to the central government in the provinces. The main goal of the 1967 change was to get rid of provincial governments. They were replaced by government workers appointed by the capital, Kinshasa. This idea of central control also spread to smaller areas. Each area was led by administrators appointed by the central government.

Only local communities, like chiefdoms, still had some freedom, but not for long. The new system of a single, central government was very similar to how the country was run under colonial rule. The only difference was that from July 1972, provinces were called regions.

With the changes in January 1973, even more power was centralized. The goal was to combine political and administrative leaders. The head of each administrative area also became the president of the local party committee. This change also greatly reduced the power of traditional leaders. Claims to authority based on family history were no longer recognized. Instead, all chiefs were appointed and controlled by the state. By then, the central government had taken away all local power.

The similarity to colonial rule became even clearer in 1973. This was when "obligatory civic work" was introduced. It was known locally as Salongo, meaning "work" in Lingala. This meant one afternoon a week of required work on farms and development projects. The government said it was a revolutionary way to return to old African values of working together. It was meant to get people to do collective work "with enthusiasm."

However, people did not like Salongo. Many avoided it, and local leaders often ignored this. Even though not following the rule could lead to jail time, most people in Zaire avoided Salongo by the late 1970s. By bringing back a disliked part of colonial rule, this forced work made people trust Mobutu's government less.

Growing Problems and Conflicts

In 1977 and 1978, rebels from Katanga, based in Angola, attacked the Katanga Province (renamed "Shaba" in 1972) twice. These attacks were called Shaba I and Shaba II. Western countries, especially the U.S., helped Zaire's military push the rebels out.

The Battle of Kolwezi happened in May 1978. During this battle, soldiers were dropped from planes to rescue Zairian, Belgian, and French miners. These miners were being held hostage by rebels.

Pope John Paul II visited Zaire on May 2, 1980. This was 100 years after Catholic missionaries first came to the country. During his visit, he met over a million people. He was the first Pope to visit Africa as a "messenger of peace." He left Zaire four days later. Sadly, 9 people died trying to attend a mass.

In 1981, Zaire started an economic plan to improve its economy. This was to help pay back its huge debt of $4.4 billion. The economy had shown some small growth in late 1980.

During the 1980s, Zaire remained a one-party state. Mobutu kept control, but opposition groups, like the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS), were active. Mobutu's attempts to stop these groups were criticized by other countries.

As the Cold War ended, Mobutu faced more pressure from inside and outside the country. In late 1989 and early 1990, Mobutu's power weakened. This was due to protests, international criticism of human rights, a struggling economy, and government corruption. Mobutu was known for taking a lot of government money for himself. In June 1989, Mobutu visited Washington, D.C.. He was the first African leader invited to meet the new U.S. President, George H. W. Bush.

In May 1990, Mobutu agreed to allow multiple political parties and elections. He also agreed to a new constitution. But when the changes were delayed, soldiers started looting Kinshasa in September 1991. They were protesting because they had not been paid. Two thousand French and Belgian soldiers arrived to help evacuate 20,000 foreign citizens.

In 1992, a large meeting called the Sovereign National Conference was held. It included over 2,000 representatives from different political parties. This conference took on the power to make laws. It elected Archbishop Laurent Monsengwo Pasinya as its leader. Étienne Tshisekedi wa Mulumba, leader of the UDPS, was chosen as prime minister. By the end of the year, Mobutu had created his own rival government. This led to a deadlock. In 1994, the two governments merged into the High Council of Republic–Parliament of Transition (HCR–PT). Mobutu remained head of state, and Kengo wa Dondo became prime minister. Elections were planned many times over the next two years, but they never happened.

The First Congo War and the End of Zaire

By 1996, problems from the nearby Rwandan Civil War and genocide spread to Zaire. Rwandan Hutu militia groups, who had fled Rwanda, were using refugee camps in eastern Zaire. From these camps, they launched attacks against Rwanda. These Hutu militia groups soon joined with Zaire's army (FAZ). They started a campaign against Congolese ethnic Tutsis in eastern Zaire, known as the Banyamulenge. In response, these Zairian Tutsis formed their own group to defend themselves. When the Zairian government increased its attacks in November 1996, the Tutsi groups rebelled against Mobutu. This started the First Congo War.

Other opposition groups soon joined the Tutsi group. They were also supported by countries like Rwanda and Uganda. This group, led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, was called the Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo-Zaïre (AFDL). The AFDL now wanted to remove Mobutu from power. They made big military gains in early 1997. By mid-1997, they had taken over almost the entire country. The only thing that slowed them down was the country's poor roads and river transport. After peace talks between Mobutu and Kabila failed, Mobutu fled to Morocco on May 17. Kabila declared himself president and took control. Three days later, he marched into Kinshasa without anyone stopping him. On May 21, Kabila officially changed the country's name back to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

What Zaire Left Behind

After Zaire ended, different groups tried to continue its legacy. These groups were led by Mobutu's former supporters and family members. They included political parties like the Union of Mobutist Democrats. Some of these groups still used Zaire's symbols and traditions. In 2024, a politician named Christian Malanga tried to overthrow the Congolese government. He called his group "New Zaire" and raised the old flag of Zaire in Kinshasa. The attempt failed, and Malanga was killed.

How Zaire Was Governed

The country was ruled by the Popular Movement of the Revolution. This was the only political party allowed by law. Even though the constitution technically allowed two parties, the MPR was the only one allowed to choose a candidate for the 1970 presidential election. Mobutu was confirmed as president with an incredibly high number of votes. In parliamentary elections held two weeks later, voters were given only one list of MPR candidates. This list was approved by over 99 percent of voters.

The president was the head of Zaire. His job was to choose and remove government ministers. He also decided what their responsibilities were. The ministers, who led their departments, were to carry out the president's plans. The president also had the power to choose and remove provincial governors. He also appointed judges for all courts, including the highest court.

The parliament, which used to have two parts, was replaced by one body called the Legislative Council. Provincial governors were no longer elected by local assemblies. Instead, they were appointed by the central government. The president could make rules on many matters without needing a law from the council. Under certain conditions, the president could rule by special orders that had the power of law.

Mobutism: The Guiding Ideas

The main ideas of Mobutu's rule were explained in the Manifesto of N'sele. This document was released in May 1967 from the president's home. The key ideas of what became known as "Mobutism" were nationalism, revolution, and authenticity.

Nationalism meant becoming economically and politically independent. Revolution was described as a "truly national revolution." It meant rejecting both capitalism and communism. So, "neither right nor left" became a slogan for the government, along with "authenticity."

In the 1970s and 1980s, Mobutu's government used a group of skilled experts. These experts were often called the "nomenklatura." The president chose and regularly changed these individuals. They led various government departments and ministries. Among them were respected people like Djamboleka Lona Okitongono. He became Secretary of Finance and later Governor of the Bank of Zaire. Mobutu kept the most important jobs, like Defense, for himself.

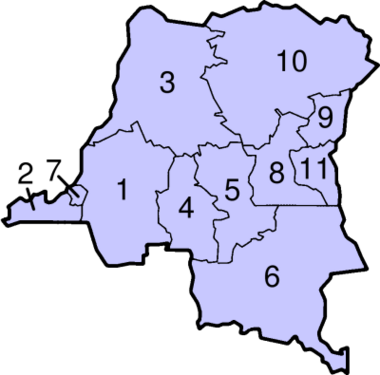

How Zaire Was Divided

Zaire was divided into 8 regions, with its capital Kinshasa. In 1988, the Kivu province was split into three regions. They were renamed provinces in 1997.

| 1. Bandundu | |

| 2. Bas-Congo | |

| 3. Équateur | |

| 4. Kasaï-Occidental | |

| 5. Kasaï–Oriental | |

| 6. Shaba | |

| 7. Kinshasa | |

| 8. Maniema | |

| 9. North Kivu | |

| 10. Orientale | |

| 11. South Kivu |

Zaire's Economy

The zaïre was the new national money, replacing the franc. One zaïre was equal to 100 makuta. The makuta was also divided into 100 sengi. However, the sengi was worth very little. The smallest coin was for 10 sengi. The money and the cities mentioned earlier had already been renamed between 1966 and 1971.

While the country became more stable after Mobutu took power, its economy started to get worse. By 1979, people could buy only 4% of what they could buy in 1960. Starting in 1976, the IMF gave loans to Mobutu's government to help stabilize it. However, much of this money was misused by Mobutu and his close friends.

A report in 1982 said that the corrupt system in Zaire would ruin all efforts to help its economy. It stated there was "no chance" that lenders would get their money back. Yet, the IMF and the World Bank continued to lend money. This money was either misused or "wasted on huge projects." Programs that were required for IMF loans cut support for health care, education, and roads.

Culture in Zaire

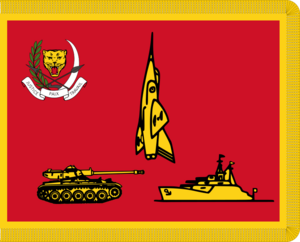

The idea of authenticity came from the MPR's belief in "authentic Zairian nationalism." This meant rejecting regionalism and tribalism. Mobutu said it meant being aware of one's own identity and values. It also meant feeling comfortable in one's own culture. Following this idea, the country's name was changed to the Republic of Zaire on October 27, 1971. The army was also renamed the Zairian Armed Forces (FAZ).

This decision was interesting because the name Congo came from the Congo River and the old Kongo Empire. Both were truly African. But Zaire was actually a Portuguese mistake of another African word, Nzadi ("river"). General Mobutu changed his name to Mobutu Sésé Seko. He made all citizens adopt African names. Many cities were also renamed.

Here are some of the name changes:

- Léopoldville became Kinshasa

- Stanleyville became Kisangani

- Élisabethville became Lubumbashi

- Jadotville became Likasi

- Albertville became Kalemie

Also, in 1972, people were encouraged to use Zairian names instead of Western or Christian ones. They also stopped wearing Western clothes and started wearing the abacost. These changes were promoted as ways to show authenticity.

Mobutu used the idea of authenticity to support his own leadership style. He said, "in our African tradition there are never two chiefs... That is why we Congolese... have decided to unite all citizens under one national party."

People who criticized the government quickly pointed out the problems with Mobutism. They said it was self-serving and unclear. However, the MPR's training center, the Makanda Kabobi Institute, worked hard to spread Mobutu's teachings. Members of the MPR Political Bureau were responsible for keeping and explaining Mobutism.

The MPR got much of its power from the idea of large, single parties that were common in Africa in the 1960s. This idea also inspired other political groups. The MPR tried to connect itself to this heritage to gain support from the people of Zaire. The idea of Mobutism was closely linked to the vision of one big party that reached every part of the nation.

See also

In Spanish: Zaire para niños

In Spanish: Zaire para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |