History of the Democratic Republic of the Congo facts for kids

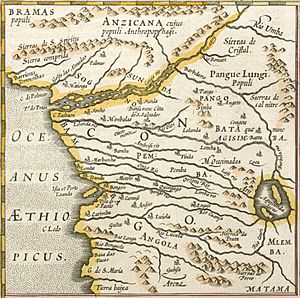

The land that is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo has been home to people for a very long time, about 90,000 years! The first big kingdoms, like Kongo, Lunda, Luba, and Kuba, started to appear in the southern grasslands around the 1300s.

The Kingdom of Kongo was a powerful state in central Africa from the 1300s to the early 1800s. It had a huge population, possibly up to 500,000 people. Its capital city was Mbanza-Kongo. In the late 1400s, Portuguese sailors arrived. This led to a time of growth for the kingdom. However, the Portuguese also wanted enslaved people. King Afonso I (1506–1543) allowed raids to capture people from nearby areas for the Portuguese. After his rule, the kingdom faced many challenges.

From about 1500 to 1850, the Atlantic slave trade took many people from the west coast of Africa. The area around the Congo River was hit the hardest. About 4 million people were taken from a 400 km (250 mi) stretch of coastline. They were sent across the Atlantic Ocean to work on sugar farms in Brazil, the US, and the Caribbean. By 1780, over 15,000 people were shipped each year from the Loango Coast.

In 1870, explorer Henry Morton Stanley explored this region. Later, in 1885, King Leopold II of Belgium started to colonize the area. He called it the Congo Free State. It took many years to control such a large territory. Outposts were built to spread the state's power. In 1885, the Force Publique, a colonial army, was created. It had white officers and black soldiers. In 1886, Camille Jansen became the first Belgian governor-general. Christian missionaries also arrived, hoping to convert local people. A railway was built in the 1890s between Matadi and Stanley Pool. Reports of very harsh treatment in the rubber plantations caused anger around the world. Because of this, the Belgian government took control from Leopold II in 1908. They renamed the area the Belgian Congo.

After some unrest, Belgium gave Congo its independence in 1960. But the country remained unstable. This led to the Congo Crisis. Some regions, like Katanga and South Kasai, tried to become independent with Belgium's help. Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba tried to stop this. He got help from the Soviet Union during the Cold War. This made the United States support a takeover led by Colonel Joseph Mobutu. Lumumba was later handed over to the Katangan government and killed in 1961. The attempts at independence were eventually stopped. After the Congo Crisis ended in 1965, Mobutu took complete power. He renamed the country Zaire. He wanted to make the country more African. He changed his own name to Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga. He also asked citizens to change their Western names to traditional African names. Mobutu stopped any opposition to his rule throughout the 1980s. But in the 1990s, his power weakened. He had to agree to share power with opposition parties. He remained the head of state and promised elections, but they never happened.

During the First Congo War, Rwanda invaded Zaire. Mobutu lost his power in 1997. Laurent-Désiré Kabila took over and renamed the country the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Soon after, the Second Congo War began. Many African nations got involved, and millions of people were killed or forced to leave their homes. Laurent-Désiré Kabila was killed by his bodyguard in 2001. His son, Joseph Kabila, took his place. Joseph Kabila was later elected president in 2006. He worked for peace. Foreign soldiers stayed for a few years, and a power-sharing government was set up. Joseph Kabila later took full control. He was re-elected in 2011 in an election that had some disagreements. In 2018, Félix Tshisekedi was elected president. This was the first peaceful transfer of power since independence.

Contents

Early History of the Congo

The land we now call the Democratic Republic of the Congo has been lived in for at least 90,000 years. In 1988, a very old harpoon, called the Semliki harpoon, was found at Katanda. It is believed to have been used to catch large river fish.

The Kingdom of Kongo existed from the 1300s to the early 1800s. Before the Portuguese arrived, it was a strong power in the region. Other important groups included the Kingdom of Luba, the Kingdom of Lunda, the Mongo people, and the Anziku Kingdom.

Colonial Rule in Congo

Congo Free State (1885–1908)

The Congo Free State was a territory controlled by Leopold II of Belgium. He managed it through a private organization. Leopold was the only owner and leader. This state covered the entire area of what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Under Leopold II, the Congo Free State became known for its terrible conditions.

Reports from people like British Consul Roger Casement showed that many people suffered greatly. They were forced to collect rubber, and if they didn't meet their quotas, they faced harsh punishments. There were many deaths due to violence, starvation, and diseases. It's hard to know the exact number of people who died because no full count was done until 1924. Roger Casement's report in 1904 estimated that about ten million people died.

Newspapers in Europe and the U.S. shared these stories with the public in 1900. By 1908, people and governments around the world put pressure on Leopold II. Because of this, he had to give control of the Congo to the Belgian government. It then became the Belgian Congo colony.

Belgian Congo (1908–1960)

On November 15, 1908, King Leopold II officially gave up his personal control of the Congo Free State. The country was renamed the Belgian Congo. It was then directly managed by the Belgian government and its Ministry of Colonies.

Belgian rule in the Congo was based on three main groups: the government, Christian missionaries, and private companies. Belgian businesses were given special treatment. This meant a lot of money went into the Congo, and different regions focused on producing specific goods. The government and private companies worked closely together. The government helped companies stop worker strikes and other problems caused by the local people.

The country was divided into many smaller areas, like a set of nesting dolls. These areas were all run the same way, following a "native policy." This was different from how the British and French often ruled, where they kept traditional leaders in charge under their watch. There was also a lot of racial segregation. Many white people moved to the Congo after World War II. They came from all walks of life but were always treated as better than black people.

In the 1940s and 1950s, more and more people moved to cities in the Congo. The colonial government started programs to make the territory a "model colony." They made big improvements in treating diseases like African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). One result was the growth of a new middle class of educated Africans, called évolués, in the cities. By the 1950s, the Congo had twice as many people working for wages as any other African colony.

The Congo had many rich natural resources, including uranium. Much of the uranium used by the U.S. in its nuclear program during World War II came from the Congo. This made both the Soviet Union and the United States very interested in the region as the Cold War began.

Rise of Congolese Political Activity

After World War II, a new group of educated Africans, called évolués, emerged in the Congo. They formed an African middle class. They held skilled jobs like clerks and nurses, which became available due to the growing economy. To be an évolué, you generally needed to know French well, be Christian, and have some education after primary school.

At first, évolués wanted special privileges in the Congo. But there were not many chances for them to move up in the colonial system. So, they formed elite clubs where they could enjoy small privileges. These clubs made them feel different from the general Congolese population. Other groups, like worker unions and ethnic groups, also helped Congolese people organize. One important group was the Alliance des Bakongo (ABAKO). It represented the Kongo people from the Lower Congo region. However, the Belgian government limited what these groups could do.

By the 1950s, most évolués were mainly concerned about unfair treatment by the Belgians. They didn't think about self-government until 1954. That year, Joseph Kasa-Vubu took over ABAKO. Under his leadership, the group became more against colonial rule. They wanted the Kongo regions to be independent. In 1956, some Congolese thinkers suggested a 30-year plan for independence. ABAKO quickly demanded "immediate independence."

The Belgian government was not ready to grant independence. Even when they started to think about decolonization in 1957, they expected to control the process. In December 1957, the colonial government allowed local elections and the formation of political parties. Congolese people mostly supported their own groups, not Belgian ones.

In 1958, a feeling of Nationalism grew. More évolués met each other and discussed what an independent Congo would look like. However, most political groups were still based on tribes and regions. In Katanga, different tribal groups formed CONAKAT. Led by Godefroid Munongo and Moïse Tshombe, this group wanted their province to be independent and stay close to Belgium.

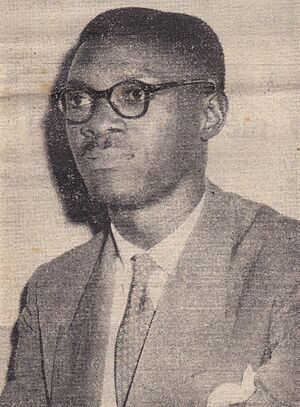

In October 1958, a group of évolués in Léopoldville, including Patrice Lumumba, formed the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC). This party wanted to achieve independence peacefully. It aimed to educate people about politics and stop regionalism. Lumumba was well-known in Stanleyville, and the MNC gained many members there. Belgian officials liked the MNC's moderate stance. They allowed Lumumba to attend a conference in Ghana in December 1958. Lumumba was very impressed by the ideas of Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah. He returned to the Congo with a more radical plan for his party. He spoke at a large rally in Léopoldville and demanded the country's "true" independence.

Fearing they were being left behind, Kasa-Vubu and ABAKO announced their own rally for January 4, 1959. The city government only approved a "private meeting." On the day of the rally, ABAKO leaders told the crowd it was postponed. But the crowd was angry. They started throwing stones at the police and damaging European property. This led to three days of violent riots. The Force Publique, the colonial army, stopped the revolt with much force. Kasa-Vubu and his helpers were arrested. These riots were different because they were mainly by uneducated city residents, not évolués. People in Belgium were very shocked. An investigation found that the riots were caused by unfair treatment, overcrowding, unemployment, and the desire for more political power. On January 13, the government announced some changes. King Baudouin declared that Congo would get independence in the future.

Meanwhile, there were disagreements within the MNC. Some leaders were bothered by Lumumba's strong control. Lumumba and Albert Kalonji also had problems. Kalonji was making the Kasai branch only for the Luba tribe, which angered other tribes. This led to the MNC splitting into two groups: MNC-Lumumba (MNC-L) led by Lumumba, and MNC-Kalonji (MNC-K) led by Kalonji. The latter group wanted a federal system.

Lumumba, now leading his own group, pushed harder for independence. After a riot in Stanleyville in October, he was arrested. Still, his influence and that of MNC-L grew quickly. His party wanted a strong, unified country, nationalism, and the end of Belgian rule. They started working with regional groups. The Belgians and more moderate Congolese were worried by Lumumba's strong views. With some support from the colonial government, the moderates formed the Parti National du Progrès (PNP). It wanted a central government and close ties with Belgium.

Independence and the Congo Crisis (1960–1965)

After the riots in Léopoldville (January 1959) and Stanleyville (October 1959), the Belgians realized they could not control such a huge country. The demands for independence were too strong. Belgian and Congolese leaders held a meeting in Brussels starting on January 18, 1960.

At the end of the meeting, on January 27, 1960, it was announced that elections would be held in the Congo on May 22, 1960. Full independence would be granted on June 30, 1960. The elections resulted in Patrice Lumumba becoming prime minister and Joseph Kasavubu becoming president.

After independence, the country was named "Republic of the Congo." Another French colony, Middle Congo, also chose this name. So, the two countries were often called Congo-Léopoldville and Congo-Brazzaville, after their capital cities.

In 1960, the country was very unstable. Local tribal leaders had much more power than the central government. When the Belgian administrators left, there were almost no skilled people left to run the country. The first Congolese person only graduated from university in 1956. Very few people in the new nation knew how to manage such a large country.

On July 5, 1960, Congolese soldiers rebelled against their European officers in the capital. Widespread looting began. On July 11, 1960, Katanga, the richest province, broke away under Moise Tshombe. The United Nations sent 20,000 peacekeepers to protect Europeans and try to restore order. Western fighters, often hired by mining companies, also came into the country. During this time, Congo's second richest province, South Kasai, also declared its independence on August 8, 1960.

After trying to get help from the United States and the United Nations, Prime Minister Lumumba asked the USSR for help. Nikita Khrushchev agreed to send weapons and experts. The United States saw the Soviet presence as an attempt to gain influence in Africa. UN forces were told to stop any weapons shipments into the country. The United States also wanted to replace Lumumba. President Kasavubu disagreed with Lumumba and wanted an alliance with the West. The U.S. sent weapons and CIA staff to help forces allied with Kasavubu.

On August 23, the Congolese army invaded South Kasai and harmed many Luba people. Lumumba was removed from office on September 5, 1960, by Kasavubu. Kasavubu publicly blamed him for the events in South Kasai and for involving the Soviets. On September 14, 1960, with CIA support, Colonel Joseph Mobutu overthrew the government. He arrested Lumumba. A new government, run by experts, was set up.

On January 17, 1961, Mobutu sent Lumumba to Élisabethville (now Lubumbashi), the capital of Katanga. Three weeks later, Katangan radio announced that he had escaped, which was not true. It soon became clear that he had been killed shortly after arriving.

In Stanleyville, people loyal to Lumumba set up a rival government under Antoine Gizenga. This government lasted from March 31, 1961, until it rejoined the main government on August 5, 1961. After some setbacks, UN and Congolese government forces took back the breakaway provinces of South Kasai on December 30, 1961, and Katanga on January 15, 1963.

Starting in 1964, in the east of the country, rebels called the Simbas rose up. They were supported by the Soviets and Cubans. They took a lot of land and declared a communist "People's Republic of the Congo" in Stanleyville. As the Congolese government took back land from the Simbas, the rebels started taking white people hostage. Belgian and American forces pushed the Simbas out of Stanleyville in November 1964 during a hostage rescue. Congolese government forces, helped by European fighters, fully defeated the Simba rebels by November 1965. The Simba rebels killed many Congolese and 392 Western hostages during the rebellion. Tens of thousands of people were killed in total during the stopping of the Simbas.

Zaire (1965–1997)

The government faced unrest and rebellion until November 1965. At that time, Lieutenant General Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, who was the army commander, took control of the country. He declared himself president for the next five years. Mobutu quickly made his power strong. He was elected president without opposition in 1970 for a seven-year term.

President Mobutu started a campaign to promote African culture. He renamed the country the "Republic of Zaire" in 1971. He also required citizens to use African names instead of French ones. The name "Zaire" comes from a Portuguese word, which means "river that swallows all rivers." Among other changes, Léopoldville became Kinshasa, and Katanga became Shaba.

The country had relative peace until 1977 and 1978. Then, rebels from Katanga, based in Angola, launched two invasions into the Shaba region. These rebels were pushed out with help from French and Belgian soldiers, as well as Moroccan troops. An African force stayed in the region for some time afterward.

Zaire remained a country with only one political party in the 1980s. Mobutu successfully kept control during this time. However, opposition parties, like the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS), were active. Mobutu's attempts to stop these groups drew criticism from other countries.

As the Cold War ended, Mobutu faced more pressure from inside and outside the country. In late 1989 and early 1990, Mobutu's power weakened. This was due to protests, international criticism of his human rights record, a struggling economy, and government corruption. He was known for taking large amounts of government money for himself.

In April 1990, Mobutu announced the Third Republic. He agreed to allow a limited multi-party system with free elections and a new constitution. But the reforms were delayed. In September 1991, soldiers started looting Kinshasa to protest their unpaid wages. Two thousand French and Belgian troops arrived to help evacuate 20,000 foreign citizens in Kinshasa.

In 1992, a large meeting called the Sovereign National Conference was held. It had over 2,000 representatives from different political parties. This conference took on the power to make laws. It elected Archbishop Laurent Monsengwo Pasinya as its chairman and Étienne Tshisekedi, leader of the UDPS, as prime minister. By the end of the year, Mobutu had created a rival government with his own prime minister. This led to a deadlock. In 1994, the two governments merged into a new body, with Mobutu as head of state and Kengo Wa Dondo as prime minister. Elections were planned many times over the next two years, but they never happened.

Civil Wars (1996–2003)

First Congo War (1996–1997)

By 1996, problems from the war and terrible killings in neighboring Rwanda spread into Zaire. Rwandan Hutu fighters who had fled Rwanda were using refugee camps in eastern Zaire as bases to attack Rwanda. In October 1996, Rwandan forces attacked these camps, scattering refugees. They took control of several towns.

Hutu fighters soon joined with the Zairian army to attack Congolese ethnic Tutsis in eastern Zaire. In response, these Tutsis formed their own group to defend themselves. When the Zairian government increased attacks in November 1996, Tutsi groups rebelled against Mobutu.

The Tutsi groups were soon joined by other opposition groups. They were also supported by countries like Rwanda and Uganda. This group, led by Laurent-Desire Kabila, was called the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (AFDL). The AFDL now wanted to remove Mobutu from power. They made big military gains in early 1997. Many Zairian politicians who had tried to oppose Mobutu for years saw this as a chance. After peace talks between Mobutu and Kabila failed in May 1997, Mobutu left the country on May 16. The AFDL entered Kinshasa easily a day later. Kabila named himself president and changed the country's name back to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He entered Kinshasa on May 20 and made his power strong.

In September 1997, Mobutu died in another country.

Second Congo War (1998–2003)

Kabila struggled to manage the country's problems and lost the support of his allies. To balance Rwanda's power, Ugandan troops helped create another rebel group called the Movement for the Liberation of Congo (MLC). This group was led by Jean-Pierre Bemba. They attacked in August 1998, supported by Rwandan and Ugandan troops. Soon after, Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe also got involved in the Congo's war. Angola and Zimbabwe supported the government. Six African governments involved in the war signed a ceasefire agreement in Lusaka in July 1999. But the Congolese rebels did not, and the ceasefire broke down within months.

Kabila was killed in 2001 by a bodyguard.

Kabila's son, Joseph Kabila, took his place. When he became president, Kabila called for peace talks to end the war. Kabila partly succeeded when another peace deal was made between him, Uganda, and Rwanda. This led to foreign troops seemingly leaving the country.

At one point, Ugandans and the MLC still held a 200 mi (320 km) wide section of the north. Rwandan forces controlled a large part of the east. Government forces held the west and south. There were reports that the conflict continued because people were illegally taking the country's rich natural resources. These included diamonds, copper, zinc, and coltan. The conflict started again in January 2002 due to ethnic clashes in the northeast. Both Uganda and Rwanda then stopped their withdrawal and sent in more troops. Talks between Kabila and the rebel leaders, held in Sun City, lasted six weeks, starting in April 2002. In June, they signed a peace agreement. Under this deal, Kabila would share power with former rebels. By June 2003, all foreign armies except Rwanda's had left Congo.

Few people in the Congo were untouched by the conflict. A survey in 2009 showed that three-quarters (76%) of people had been affected in some way.

Joseph Kabila's Time as President

Transitional Government (2003–2006)

The DR Congo had a temporary government from July 2003 until elections were held. Voters approved a new constitution. On July 30, 2006, the Congo held its first multi-party elections since gaining independence in 1960. Joseph Kabila received 45% of the votes, and his opponent Jean-Pierre Bemba got 20%. This led to fighting between their supporters from August 20 to 22, 2006, in the streets of the capital, Kinshasa. Sixteen people died before police and UN forces took control. A new election was held on October 29, 2006, which Kabila won with 70% of the vote. Bemba claimed there were problems with the election. On December 6, 2006, Joseph Kabila officially became president.

Kabila Stays Longer than Planned

In December 2011, Joseph Kabila was re-elected for a second term as president. After the results were announced on December 9, there was violent unrest in Kinshasa and Mbuji-Mayi. Official counts showed that many people in these areas had voted for the opposition candidate Étienne Tshisekedi. Observers from the Carter Center reported that results from almost 2,000 polling stations, where Tshisekedi had strong support, were missing from the official count. They said the election lacked credibility. On December 20, Kabila was sworn in for his second term. He promised to improve roads and public services. However, Tshisekedi said the election result was not fair and stated he intended to "swear himself in" as president too.

On January 19, 2015, protests started by students at the University of Kinshasa. The protests began after a proposed law was announced. This law would allow Kabila to stay in power until a national census could be done. Elections had been planned for 2016. By January 21, clashes between police and protesters had caused at least 42 deaths.

Similarly, in September 2016, violent protests were met with brutal force by the police and soldiers. Opposition groups claimed 80 people died, including the Students' Union leader. From Monday, September 19, people in Kinshasa and other parts of Congo were mostly confined to their homes. Police arrested anyone connected to the opposition, as well as innocent bystanders. Government messages on television and actions by secret government groups in the streets worked against the opposition and foreigners. The president's term was supposed to end on December 19, 2016. But no plans were made to elect a replacement, which caused more protests.

Félix Tshisekedi's Presidency (2019–Present)

On December 30, 2018, the presidential election was held to choose Kabila's successor. On January 10, 2019, the election commission announced that opposition candidate Félix Tshisekedi had won. He was officially sworn in as president on January 24, 2019. At the ceremony, Félix Tshisekedi appointed Vital Kamerhe as his chief of staff. In June 2020, Vital Kamerhe was found guilty of taking public money and was sentenced to 20 years in prison. However, Kamerhe was released in December 2021.

The political allies of former president Joseph Kabila, who left office in January 2019, still controlled important government departments, the parliament, courts, and security services. However, President Felix Tshisekedi managed to make his power stronger. He gained the support of almost 400 out of 500 members of the National Assembly. The pro-Kabila leaders of both houses of parliament were forced out. In April 2021, a new government was formed without Kabila's supporters. President Felix Tshisekedi successfully removed the last people in his government who were loyal to former leader Joseph Kabila. In January 2021, DRC's President Félix Tshisekedi pardoned everyone who had been found guilty in the killing of Laurent-Désiré Kabila in 2001. Colonel Eddy Kapend and others, who had been in prison for 15 years, were released.

After the 2023 presidential election, Tshisekedi had a clear lead for a second term. On December 31, 2023, officials announced that President Felix Tshisekedi had been re-elected with 73% of the vote. Nine opposition candidates signed a statement rejecting the election and called for a new one.

Ongoing Conflicts

The government and the world's largest United Nations peacekeeping force have struggled to provide safety across the huge country. This has led to the rise of up to 120 armed groups by 2018. These groups are often accused of being supported by neighboring governments. These governments are interested in Eastern Congo's vast mineral wealth. Some people believe that the national army's lack of security is part of a strategy by the government. They suggest the army profits from illegal logging and mining operations in exchange for loyalty. Different rebel groups often target civilians based on their ethnic group. Militias often form around ethnic local groups known as "Mai-Mai".

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la República Democrática del Congo para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la República Democrática del Congo para niños

- Economic history of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Former place names in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- History of Africa

- List of heads of state of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- List of heads of government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Politics of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Cities in DR Congo:

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |