Second Congo War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Second Congo War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Congo conflicts and the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide | |||||||

Congolese rebel soldiers in 2001 (top) Congolese rebel soldiers in the town of Gbadolite in 2000 (bottom) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Note: Rwanda and Uganda fought a short war in June 2000 over Congolese territory. |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Mai Mai: 20,000–30,000 militia Interahamwe: 20,000+ |

RCD-Goma: 40,000 Rwanda: 8,000+ Uganda: 13,000 |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,000 Ugandans (Kisangani only) 4,000 rebel casualties (Kinshasa only) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

The Second Congo War, also known as the Great War of Africa, started in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in August 1998. This war began just over a year after the First Congo War and involved similar problems. Many countries and armed groups from across Africa joined the fight. The war officially ended in July 2003 when a new government took power in Congo.

Even though a peace agreement was signed in 2002, fighting continued in many parts of the country, especially in the east. This conflict involved nine African countries and about twenty-five different armed groups.

Experts estimated in 2008 that the war and its effects caused over 5.4 million deaths. Most of these deaths were from sickness and not having enough food. This makes the Second Congo War the deadliest conflict worldwide since World War II. Also, about 2 million people had to leave their homes or seek safety in other countries. Conflict minerals, like diamonds and coltan, were a major way for groups to pay for the war.

Contents

Why the War Started: The Background Story

How the First Congo War Led to More Trouble

The First Congo War began in 1996. Rwanda was worried because Hutu militias were attacking from what was then called Zaire (now the DRC). These militias, mostly Hutu people, had set up camps in eastern Zaire. Many of them had fled there after the Rwandan genocide in 1994, when the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) took power.

Rwanda's government, which was mainly Tutsi, said these attacks were a problem for their country's safety. So, they started to arm the Tutsi people called Banyamulenge who lived in eastern Zaire. The government of Zaire, led by Mobutu Sese Seko, complained about this. But they were too weak to stop it or get help from other countries.

With help from Uganda, Rwanda, and Angola, Tutsi forces led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila slowly moved through Zaire. They faced little resistance from Mobutu's weak army. Most of Kabila's fighters were Tutsis and experienced soldiers. Kabila himself had been against Mobutu for a long time.

Kabila's army started moving west in December 1996. They took control of towns and mines near the border. There were reports of harsh actions by the rebel army. Some reports claimed that Kabila's Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (ADFLC) had killed many civilians.

In March 1997, Kabila's forces attacked and demanded that the government in Kinshasa surrender. The rebels quickly took more towns. Mobutu fled Kinshasa on May 16, and Kabila's forces entered the capital easily. Mobutu died in another country four months later. Kabila declared himself president on May 17, 1997. He renamed the country the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

When Friends Became Foes: Unwanted Help

When Kabila took control in May 1997, he faced many challenges. The country had huge debts, and different groups wanted power. Also, the foreign countries that helped him win, like Rwanda, did not want to leave. Many Congolese people did not like the strong Rwandan presence in their capital. They started to think Kabila was controlled by foreign powers.

Tensions grew on July 14, 1998, when Kabila fired his Rwandan chief of staff, James Kabarebe. He replaced him with a Congolese person. Two weeks later, Kabila changed his mind. He thanked Rwanda for its help but then ordered all Rwandan and Ugandan soldiers to leave the country. Rwandan military advisers in Kinshasa were quickly sent away. This order worried the Banyamulenge Tutsi people in eastern Congo. Their problems with other ethnic groups had helped start the First Congo War.

The War Begins: 1998–1999

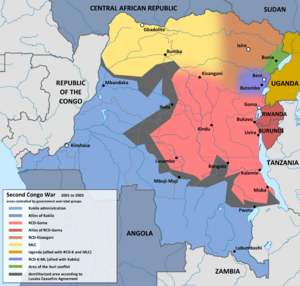

Blue – Democratic Republic of the Congo and allies

Red – Rwanda's allies

Yellow – Uganda's allies

On August 2, 1998, the Banyamulenge in Goma started a rebellion. Rwanda quickly offered them help. Soon, a strong rebel group called the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD) appeared. This group was mostly Banyamulenge and was supported by Rwanda and Uganda. The RCD quickly took control of the eastern provinces, which are rich in resources. They set up their main base in Goma.

The RCD also took the towns of Bukavu and Uvira. The Rwandan government, led by Tutsis, and Burundi also got involved, taking over parts of northeastern Congo. To fight back against the Rwandan forces, President Kabila asked for help from Hutu refugees in eastern Congo. He also encouraged people to turn against Tutsis, which led to some public attacks in Kinshasa.

Rwanda also claimed that a large part of eastern Congo was "historically Rwandan." They said Kabila was planning to harm their Tutsi relatives in the Kivu region. It is still debated whether Rwanda intervened to protect the Banyamulenge or to gain control of the region after Mobutu was removed.

In a surprising move, Rwandan soldiers took over three planes and flew them to the government base of Kitona on the Atlantic coast. These soldiers quickly convinced the local troops to join their side. More towns in the east and around Kitona fell quickly. By August 13, less than two weeks after the rebellion started, rebels controlled the Inga hydroelectric station, which provides power to Kinshasa. They also controlled the port of Matadi, where most of Kinshasa's food arrived. The diamond city of Kisangani fell on August 23. By late August, forces from the east were threatening Kinshasa. Uganda, while still supporting the RCD with Rwanda, also created its own rebel group, the Movement for the Liberation of Congo (MLC).

Fighting continued across the country. Even as rebels moved towards Kinshasa, government forces fought for control of towns in the east. The Hutu fighters working with Kabila were also strong in the east. It seemed likely that Kinshasa would fall and Kabila would be defeated.

However, the rebel attack was suddenly stopped when Kabila's efforts to get help worked. The first African countries to help Kabila were members of the Southern African Development Community (SADC). While SADC members are supposed to help each other if attacked, many stayed neutral. But the governments of Namibia, Zimbabwe, and Angola decided to support Kabila after a meeting in Harare, Zimbabwe, on August 19. Other countries like Chad, Libya, and Sudan also joined Kabila's side in the following weeks.

This started a war with many sides. In September 1998, Zimbabwean soldiers flown into Kinshasa stopped a rebel advance near the capital. Angolan forces attacked from their borders, pushing back the rebel forces. This help from other countries saved Kabila's government and pushed the rebels away from the capital. But it did not defeat the rebels, and the fighting risked direct conflict with the armies of Uganda and Rwanda.

In November 1998, a new rebel group supported by Uganda, the Movement for the Liberation of Congo, was reported in the north. On November 6, Rwandan President Paul Kagame admitted for the first time that Rwandan forces were helping the RCD rebels for security reasons. On January 18, 1999, Rwanda, Uganda, Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe agreed to a ceasefire. But the RCD was not invited, so fighting continued. Most countries outside Africa stayed neutral but urged an end to the violence.

The War Continues: 1999–2000

On April 5, 1999, problems within the RCD grew. The RCD leader, Ernest Wamba dia Wamba, moved his base to Uganda-controlled Kisangani. He formed a new group called RCD-Kisangani. Later, Uganda's President Yoweri Museveni and Kabila signed a ceasefire agreement on April 18 in Sirte, Libya. But both the RCD and Rwanda refused to join.

On May 16, Wamba was removed as head of the RCD. A pro-Rwanda leader, Dr. Emile Ilunga, took his place. Seven days later, different parts of the RCD fought each other for control of Kisangani. On June 8, rebel groups met to try and unite against Kabila. Despite these efforts, Uganda created a new province called Ituri. This led to ethnic fighting known as the Ituri conflict, sometimes called a "war within a war."

However, diplomatic efforts led to the first ceasefire of the war. In July 1999, the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement was signed by the six main countries involved: the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, and Uganda. On August 1, the MLC also signed it. The agreement said that all sides would work together to find, disarm, and record all armed groups in Congo, especially those linked to the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

But there were not many plans to actually disarm the militias. The UN Security Council sent about 90 staff members in August 1999 to watch the ceasefire. However, in the following months, all sides accused each other of breaking the ceasefire. It became clear that small incidents could easily start new attacks.

Tensions between Uganda and Rwanda grew. Their armies clashed in Kisangani on August 7. Fighting started again on August 14 and lasted until August 17, when another ceasefire was called. Both sides used heavy weapons. The fighting was caused by disagreements over their goals in the war.

In November, government TV in Kinshasa claimed that Kabila's army was ready to "liberate" the country. Rwandan-backed rebel forces launched a big attack and got close to Kinshasa, but they were pushed back.

By February 24, 2000, the UN approved a force of 5,537 troops, called the United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC). Their job was to watch the ceasefire. But fighting continued between rebels and government forces, and between Rwandan and Ugandan forces. Many clashes happened across the country, especially heavy fighting between Uganda and Rwanda in Kisangani in May and June 2000.

On August 9, 2000, a government attack in Equateur Province was stopped by MLC forces. Military actions and peace efforts by the UN, African Union, and Southern African Development Community did not make much progress.

A New Leader: 2001

The Death of President Kabila

On January 16, 2001, President Laurent-Désiré Kabila was shot and killed at the presidential palace in Kinshasa. The government first said he was hurt but alive and flown to Zimbabwe for care. The details of his death are not fully clear. Most people agree that Kabila was shot by one of his bodyguards, an 18-year-old child soldier named Rashidi Mizele.

Two days later, the government announced that Kabila had died from his injuries. His body was returned for a state funeral on January 26, 2001.

Some reports suggest that the child soldiers who had been with Kabila since 1996 were unhappy with how they were treated. The killing of 47 child soldiers, which Kabila saw the day before he died, seemed to be the main reason for the assassination.

While the role of these unhappy child soldiers is generally accepted, some have suggested that outside groups might have influenced them. Some Congolese officials blamed Rwanda, saying they planned the killing. Others have wondered if Angola or even the United States were involved. However, there is no proof that Mizele or the child soldiers were acting on orders from outside sources.

Joseph Kabila Takes Over

After his father's death, Joseph Kabila became president by a unanimous vote of the Congolese parliament. His election was largely supported by Robert Mugabe. In February, the new president met Rwandan President Paul Kagame in the United States. Rwanda, Uganda, and the rebels agreed to a UN plan to pull out troops. Uganda and Rwanda began moving their soldiers back from the front lines.

Joseph Kabila was seen as a better political leader than his father. He was educated in the West and spoke English, which gave diplomats hope for change. His father, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, had been seen as the main obstacle to peace. The peace agreement his father signed in 1999, the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement, had not been fully carried out because he kept starting new attacks and blocked UN peacekeepers.

Investigating Stolen Resources

In April 2001, a UN group looked into the illegal taking of diamonds, cobalt, coltan, gold, and other valuable resources in Congo. The report accused Rwanda, Uganda, and Zimbabwe of regularly taking Congo's resources. It suggested that the UN Security Council should put sanctions (penalties) on them.

Moving Towards Peace: 2002

In 2002, Rwanda's position in the war started to weaken. Many members of the RCD stopped fighting or joined Kabila's government. Also, the Banyamulenge, who were key to Rwanda's forces, grew tired of being controlled by Kigali (Rwanda's capital) and the endless fighting. Some of them rebelled, leading to clashes with Rwandan forces.

At the same time, the western part of Congo became safer under the younger Kabila. International aid started again as the economy improved.

In March, the RCD-Goma group captured Moliro, a town on Lake Tanganyika, from government forces. This was seen as a violation of the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement.

Peace Agreements (April–December 2002)

With South Africa's help, peace talks were held there between April and December 2002. These talks led to a "comprehensive peace agreement." The Sun City Agreement was signed on April 19, 2002. It set up a plan for Congo to have a united government with many political parties and democratic elections. However, some critics noted that it did not say how the different armies would unite, which made the agreement weaker. There were still some violations, but the fighting did reduce.

On July 30, 2002, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo signed a peace deal called the Pretoria Accord after five days of talks. The talks focused on two main things: first, the withdrawal of about 20,000 Rwandan soldiers from Congo; second, finding and disarming the Hutu militia known as Interahamwe. This group took part in Rwanda's 1994 genocide and was still active in eastern Congo. Rwanda had refused to leave until these Hutu militias were dealt with.

The Luanda Agreement, signed on September 6, made peace official between Congo and Uganda. This treaty aimed for Uganda to pull its troops out of Bunia and improve relations between the two countries. Eleven days later, the first Rwandan soldiers left eastern DRC. On October 5, Rwanda announced that all its soldiers had left. MONUC confirmed that over 20,000 Rwandan soldiers had departed.

On October 21, the UN released a report about armed groups stealing natural resources. Both Rwanda and Uganda denied that their leaders were involved in illegally trading stolen resources. On December 17, 2002, the different Congolese groups involved in the war signed the Global and All-Inclusive Agreement. This agreement outlined a plan for a temporary government that would lead to elections within two years. This marked the official end of the Second Congo War.

After the War: 2003 Onwards

The Transitional Government Takes Over

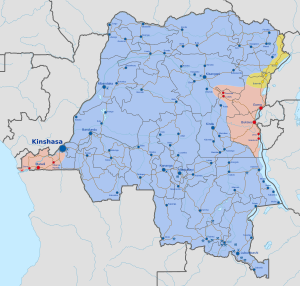

On July 18, 2003, the Transitional Government officially began, as planned in the Global and All-Inclusive Agreement. This agreement required the groups to reunite the country, disarm their fighters, and hold elections. However, there were many problems, leading to continued instability in much of the country. The national elections, planned for June 2005, were delayed until July 2006.

The main reason the Transitional Government remained weak was that the former warring groups did not want to give up their power to a central government. Some groups kept their own military control separate from the new government. Also, a lot of money was stolen by corrupt officials, which caused more problems.

On July 30, 2006, the first elections were held in the DRC after people approved a new constitution. A second round of elections took place on October 30.

Ongoing Conflicts and Challenges

The weakness of the government has allowed violence and human rights problems to continue in the east. There are three main areas where fighting still happens:

- North and South Kivu: Here, a weakened Hutu group (FDLR) still threatens the Rwandan border and the Banyamulenge. Rwanda supports RCD-Goma rebels against the government in Kinshasa (see Kivu conflict), and local conflicts continue.

- Ituri Province: The UN mission (MONUC / MONUSCO) has struggled to control the many armed groups in the Ituri conflict.

- Northern Katanga: Here, Mai-Mai militias are not fully controlled by the government in Kinshasa (see Katanga insurgency).

Ethnic violence between Hutu and Tutsi groups has been a major cause of the conflict. Both sides fear being wiped out. The government in Kinshasa and the Hutu-aligned forces worked closely because they both wanted to remove the armies and proxy forces of Uganda and Rwanda.

While Ugandan and Rwandan-backed forces worked together to gain land, they also fought each other over access to resources. There were reports that Uganda allowed Kinshasa to send weapons to the Hutu FDLR through areas controlled by Uganda-backed rebels. This was because Uganda, Kinshasa, and the Hutus all wanted to reduce Rwanda's influence.

Rwanda and Uganda's Support for Rebels

Rwanda supported rebels because it feared Hutu rebels on its border. The Kinshasa government was suspicious of Kigali's (Rwanda's capital) influence in the region. Rwanda had occupied the area many times, and some witnesses confirmed that Rwanda profited from stealing Congolese minerals. Because of this, Rwanda was accused of supporting the ongoing rebellion of General Laurent Nkunda in Congo. However, Nkunda was arrested by Rwandan police in 2009. The DRC wanted assurance that Kigali-aligned forces had no interest in conflict minerals or land in eastern Congo.

On December 19, 2005, the International Court of Justice ruled that Uganda had violated the DRC's sovereignty. It also said that the DRC had lost billions of dollars worth of resources. The DRC government has asked for $10 billion in payment. Even though the ICJ has worked to prosecute war crimes, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank rewarded both Uganda and Rwanda with debt relief. This happened even though much of their increased money came from illegally importing conflict minerals from the DRC. This situation has led to accusations that these international groups are not following international laws.

Impact on the Environment

The war caused a lot of damage to the environment. The forests of Congo are very rich in different kinds of plants and animals. The Congo Basin is the second largest tropical rainforest in the world and the biggest forest in Africa.

Animals and the Bushmeat Trade

Because of the war, the elephant population in the Democratic Republic of Congo was cut in half. The hippo population went from 22,000 to 900, and the great ape population decreased by 77%–93% between 1998 and 2015.

With up to 3.4 million people forced to leave their homes in Congo, many moved into the forests. There, they hunted bonobos, gorillas, elephants, and other animals for bushmeat (meat from wild animals) to survive. They also cleared forest land that was important for these animals. Many of these people were from cities where hunting certain animals was not a problem, or they were locals whose traditions changed because they needed to survive. For example, a 2009 study found that the Bongando people started eating bonobos, which was against their culture, because of the war. During the conflict, many battle lines were in bonobo reserves, which further reduced their numbers.

The government's instability meant that new illegal mining camps were set up deep inside Congo's forests. In these camps, bushmeat became the main source of food. Also, the large number of people entering the forests, along with dirty conditions at the mines, increased the risk of diseases for animals like gorillas. The war also stopped many efforts to protect nature in Congo. This allowed many armed groups to openly engage in poaching (illegal hunting).

The danger from rebel forces during the war caused many military officers who controlled city trade to leave their jobs. This created an open market for bushmeat and pet trade, which was then taken over by lower-ranked soldiers looking to make money. As a result, the sale of protected animals in city markets in northeastern Congo, near Garamba National Park, increased five times. In other northern parts of Congo, studies found a 23% increase in protected animal sales.

Deforestation and Forest Loss

The war led to a loss of 1.31% of Congo's forests, which is about the size of Belgium.

Millions of displaced people caused large-scale logging and cutting down of trees to create farmland. These activities had a big impact because of the edge effect from forest fragmentation (when large forests are broken into smaller pieces).

Virunga National Park, Africa's oldest national park, became the first UN World Heritage Site to be endangered. Its plants were cleared during both the first and second Congo wars to make way for the Rwandan and Congolese armies.

See also

In Spanish: Segunda guerra del Congo para niños

In Spanish: Segunda guerra del Congo para niños

- Dongo conflict, 2009 conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Living in Emergency: Stories of Doctors Without Borders – documentary film about the work of Médecins Sans Frontières in DR Congo

- Child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of Congo

General:

- List of conflicts in Africa

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |