Peter Force facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Peter Force

|

|

|---|---|

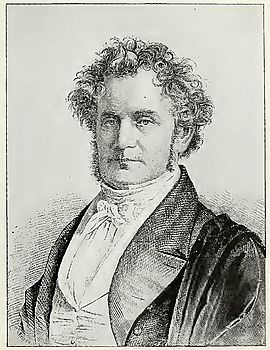

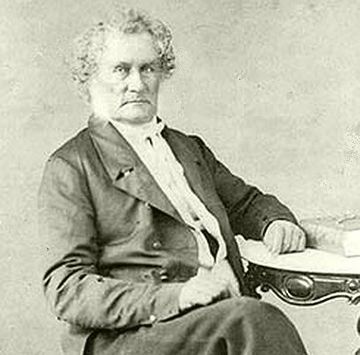

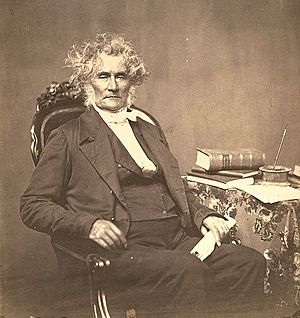

Peter Force in 1858

Photograph by Mathew Brady |

|

| 12th Mayor of the City of Washington, DC | |

| In office June 13, 1836 – June 8th, 1840 |

|

| Preceded by | William A. Bradley |

| Succeeded by | William Winston Seaton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 26, 1790 Passaic Falls, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | January 23, 1868 (aged 77) |

| Resting place | Rock Creek Cemetery Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Whig Party |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Peter Force Collection in The Library of Congress |

Peter Force (born November 26, 1790 – died January 23, 1868) was an important American figure. He was a politician, newspaper editor, printer, and historian. He was elected Mayor of Washington D.C. twice.

During his life, he collected a huge and valuable library of books, old papers, and maps. These came from important people during the American Revolution. His collection was one of the biggest and best of its kind. Force also served as a lieutenant in the militia during the War of 1812. He was a member of the Whig Party and supported John Quincy Adams.

Force is best known for publishing many historical documents, books, and maps about the American colonies and the Revolution. The Library of Congress later bought this massive collection. He also started a political journal and other publications. He was president of a national science society and a printing society. During the American Civil War, the Lincoln Administration sent Force to Europe. His mission was to help keep good relations with France and England.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Peter Force was born near the Passaic Falls in New Jersey. His parents were William Force and Sarah Ferguson. His father, William, was a soldier in the Revolutionary War. Peter's interest in history was greatly inspired by his father's service.

Force grew up in New Paltz, New York. Later, he moved to New York City and learned the printing trade. He married Hannah Evans, and they had ten children. One of their sons, Manning Force, became a famous Major General in the Civil War. People described Peter Force as quiet and reserved, but also friendly.

In 1812, Force joined the New York Typographical Society. This was a trade union for printers in the city. He quickly became a director and then president of the society. He served as president from 1813 to 1815.

During the War of 1812, Force served in the New York State Militia. He rose through the ranks to become a Sergeant and then a Lieutenant.

Moving to Washington D.C.

Force started his career as a printer for William A. Davis in New York City. He was so good that he became the office director at just 16 years old. In 1815, his employer got a contract to print for Congress. So, Davis moved to Washington, D.C.. Peter Force, then 25, followed him and also became a printer in the city.

He soon partnered with Davis, working as a foreman for the congressional printing plant. In 1816, he joined the Columbia Typographical Society. He later became its first "free member" in 1826. After Davis left the partnership, Force formed other successful printing businesses.

Early in his time in Washington, Force caught the attention of important leaders. He remained a leading figure in the city throughout his life.

Public Service and Publications

Four years after moving to Washington, Force started publishing an annual book. This book recorded facts about early American history. It included official and statistical information. From 1820 to 1836, he published the National Calendar. This later became the National Calendar and Annals of the United States.

In the 1820s, Force was a member and president of the Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences. From 1823 to 1830, Force published the National Journal. This newspaper shared moderate views on public issues. It became the official newspaper during John Quincy Adams' presidency. Even Adams himself sometimes wrote for it. The journal became a daily newspaper in 1824. Force stopped being its editor in 1830.

From 1820 to 1828, Force also put together and published the Biennial Register. This was the official directory for the U.S. government. In 1827, he printed a large update for the Library of Congress catalog.

Force was also a member of the Smithsonian Institution and the United States Naval Observatory. He helped create the American Historical Society in Washington in 1836. In 1822, he received a U.S. Patent for a color printing method. He also donated a stone to the Washington Monument.

Political Career

After strongly supporting John Quincy Adams' election as president in 1824, Force became active in local politics. He served as a councilman and then an alderman. He was chosen president of both groups.

He was elected Mayor of Washington in 1836 and again in 1838. He ran as a member of the Whig Party. Later, he became president of the National Institute for the Promotion of Science. In 1851, Force was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society.

Until the 1850s, the Library of Congress did not have a good map collection. Peter Force was on a committee that approved a plan for a new geographical department in 1856. Many rare maps from Force's own collection were given to this new department.

Civil War Efforts

In November 1861, President Lincoln's administration sent Force to Europe. He went on a diplomatic mission to Paris and London. The goal was to improve relations with the Union during the American Civil War. Force traveled with Archbishop Hughes and Bishop McIlvaine. They hoped to convince the European governments not to help the Confederacy. Force successfully built strong relationships with British and French leaders.

When he returned to America in June 1862, he received the "Freedom of the City" honor from New York. The Typographical Society also thanked him for his important mission. They praised his efforts in convincing Europe to support the Union.

During the Civil War, Peter's son, Manning Force, became a major-general. He fought in the Battle of Vicksburg and served under William Tecumseh Sherman. Peter and his son wrote to each other often during the war.

In 1862, during the Northern Virginia campaign, Confederate General Robert E. Lee's army came close to Washington D.C. A Union colonel offered to hide Force's large library of American history books. He was worried about a possible attack on the capital. However, Force refused the offer.

Historian and Published Works

Force had a special way of collecting and publishing historical documents. Unlike some other historians of his time, he rarely added his own notes. He wanted the original documents to speak for themselves. Force believed that no old paper should ever be changed. He thought nothing should be added or replaced. This was different from others who might correct grammar or change meanings in old texts. Force strongly disagreed with such practices.

Force was the first historian to realize that the "Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence of 1775" was not what it seemed. He later published his findings on this topic.

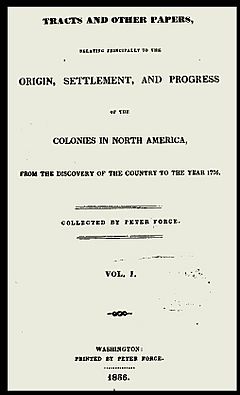

Force's biggest achievement was collecting and editing historical documents. He published Tracts and Other Papers, Relating Principally to the Origin, Settlement, and Progress of the Colonies in North America. This four-volume work (1836–1846) included rare pamphlets. His nine-volume American Archives (1837–1853) was a collection of the most important documents from the American Revolution, covering 1774–1776.

In 1833, the U.S. Government hired him to prepare and publish his huge collection. He carefully arranged nine volumes. However, after the ninth volume was delivered, officials did not review the manuscripts. The project stopped, even though Force wanted to continue. He had many more important documents ready to print. Force tried to get officials to restart the project for over 30 years, but he eventually had to give up.

Twenty large volumes were planned, but only the first nine were published. Matthew St. Clair Clarke and Force were co-publishers of American Archives. Force's dream of contributing to the Library of Congress finally came true in 1867. Congress bought his collection of original documents for $100,000. This greatly expanded the Library of Congress under librarian Ainsworth Rand Spofford.

Force's Collection

For years, Force traveled the eastern United States. He searched bookshops and attended auctions from Boston to Charleston. He was always looking for rare books and papers. He often won bids at auctions because others didn't know the true value of the items. Once, he bought a collection of Boston Revolutionary newspapers. When people from New England complained, he asked, "Why didn't you buy them yourselves, then?" Force was determined to get complete collections of all Washington newspapers. After 30 years, his collection nearly filled his home's basement.

In 1867, a committee from Congress examined Peter Force's library. It was enormous, with about 150,000 items. The committee spent two to three hours a day for two months examining every document, manuscript, and map. They found Force's collection to be very complete. It included early American travel books in many languages. It also had an unmatched collection of books and pamphlets about American colonial politics.

Among the most valuable items were original military maps from the French and Indian War and the American Revolutionary War. Many of these maps were drawn by officers from both the American and British armies. The collection had about 300 hand-drawn maps covering the entire United States. It also included 48 large volumes with rare historical signatures. In 1875, Peter Force's son, William Q. Force, donated more personal papers to the Library of Congress.

It took until the late 1900s for the full value of Force's collection to be recognized. His vast archives held the only surviving copies of many important documents from the colonial and revolutionary periods. These became a valuable resource for scholars. Many large libraries worldwide have Force's nine published volumes. However, they are not used as much as they could be. Scholars find the huge work hard to navigate because of its complex index. In 2001, Northern Illinois University and the University of Georgia received a grant. This allowed them to put Force's American Archives online for free.

Final Years

Peter Force continued collecting books, newspapers, and documents until the week before he died. He passed away on January 23, 1868, at age 77. He is buried next to his wife in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington D.C. His grave marker is a 16-foot tall marble obelisk. It was designed by German sculptor Jacques Jouvenal. The obelisk has a carving of a bookshelf filled with books.

The Peter Force School opened in Washington D.C. in 1879. It was torn down in 1962.

See also

- John Clement Fitzpatrick - historian and archivist of the Papers of George Washington

- Worthington C. Ford – archivist of Washington and early American history

- William Wright Abbot - archivist who did extensive work editing and publishing papers of George Washington

- Howard Henry Peckham – prominent early American archivist

- Antiquarian

- Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America

- James Kendall Hosmer, writer, historian and librarian

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |