Vaquita facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Vaquita |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

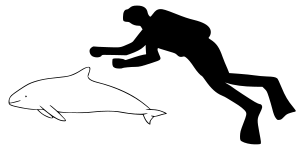

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Phocoenidae |

| Genus: | Phocoena |

| Species: |

P. sinus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Phocoena sinus Norris & McFarland, 1958

|

|

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

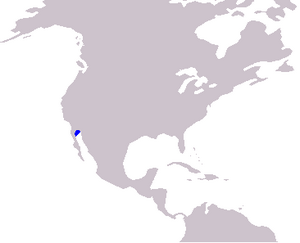

The vaquita (Phocoena sinus) is a very rare type of porpoise. It lives only in the Gulf of California in Mexico. This amazing animal is currently on the edge of extinction. It is listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN Red List.

The main reason for its sharp decline is getting caught by accident in gillnets. These nets are used by people fishing illegally for a fish called totoaba.

Contents

What is a Vaquita?

The vaquita was first officially described as a species in 1958. Two zoologists, Kenneth S. Norris and William N. McFarland, studied their skulls. It wasn't until 1985 that scientists could fully describe what they looked like.

The word "Vaquita" means "little cow" in Spanish. This name fits because they are quite small.

Vaquita Family Tree

The vaquita belongs to a group of porpoises called Phocoena. Most porpoises in this group live near coastlines. The vaquita is most closely related to Burmeister's porpoise. It is also related to the spectacled porpoise. These two relatives live far away in the Southern Hemisphere.

Scientists believe the vaquita's ancestors moved north over 2.5 million years ago. This happened during a cooler period in Earth's history. Genetic studies show that vaquitas went through a big population drop in the past. This might explain why the few remaining vaquitas are still healthy today.

Vaquita Appearance

The vaquita is the smallest living cetacean. Cetaceans are a group of marine mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. You can easily tell a vaquita apart from other animals in its home.

It has a small body with a tall, triangular fin on its back. Its head is rounded, and it does not have a distinct beak. Vaquitas are mostly grey. Their backs are darker, and their bellies are white. They have clear black patches around their lips and eyes.

Size Differences

Male and female vaquitas have different body sizes. This is called Sexual dimorphism. Adult females are longer than males. They also have bigger heads and wider flippers. Females can grow to about 150 cm (4.9 ft) long. Males reach about 140 cm (4.6 ft). The fin on the male's back is taller than the female's.

Where Vaquitas Live

The vaquita's home is a very small part of the upper Gulf of California. This area is also known as the Sea of Cortez. This makes it the smallest living area for any marine mammal. They prefer shallow, cloudy waters that are less than 150 meters (490 ft) deep.

What Vaquitas Eat

Vaquitas eat a variety of food. They are not picky eaters. They hunt for different types of fish that live near the seabed. They also eat crustaceans like crabs and shrimp, and squids. Most of their diet is made up of fish like grunts and croakers.

Vaquita Social Life

Vaquitas are usually seen alone or in pairs. Sometimes, a pair will have a calf with them. They have been seen in small groups of up to 10 individuals.

Vaquita Life Cycle and Reproduction

Scientists don't know much about the vaquita's life cycle. They are thought to live for about 20 years. Vaquitas become old enough to have babies between 3 and 6 years of age. Early studies suggested they had a calf every two years. However, recent observations show they might be able to reproduce every year. It is believed that male vaquitas compete to mate with females.

Vaquita Population Status

We don't know how many vaquitas there were in the past. This is because they were only fully described in the late 1980s. In 1997, the first full survey estimated about 567 vaquitas. By 2007, the number had dropped to 150.

As of 2018, it was thought there were fewer than 19 vaquitas left. By February 2022, the number was estimated to be fewer than 10. In 2023, the estimate was still around 10 in the wild. A survey in 2024 saw a minimum of 6 to 8 individuals. This is the lowest count ever. However, this might be because the survey area was small. Vaquitas can move in and out of that area.

Threats to Vaquitas

Fishing Nets: The Biggest Danger

The vaquita population has dropped sharply because they get caught in fishing nets. These are called gillnets. They are used by both legal and illegal fisheries. Fishermen target fish like shrimp and the Totoaba fish. The totoaba is also an endangered fish.

The Mexican government has tried to help. They banned some gillnets in 2015. They also created a permanent gillnet exclusion zone in 2017. But illegal fishing still happens in the vaquita's home. This is why the population keeps shrinking.

Other Dangers

Vaquitas live close to the coast. This means they are exposed to changes in their habitat. They can also be affected by pollution from land. While other threats exist, getting caught in fishing nets is the single biggest danger to the vaquita's survival.

Some fishermen have reported seeing parts of vaquitas in shark stomachs. This suggests that sharks might sometimes eat vaquitas. However, fishing fleets can also reduce the number of sharks. This might indirectly help marine mammals. But the harm from accidental catches in fishing nets is much greater than any benefit from fewer sharks.

Protecting Vaquitas

Vaquita Conservation Status

The vaquita is listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List. This means it is just one step away from being completely gone from the wild. It is considered the most endangered marine mammal in the world. The vaquita has been on this list since 1996.

In 2019, the UNESCO World Heritage Site where the last vaquitas live was listed as a World Heritage Site in Danger. This highlights how serious the situation is.

The vaquita is also protected by several laws and agreements. These include the Endangered Species Act of 1973 in the U.S. and the Mexican Official Standard NOM-059. It is also protected by CITES, which controls international trade in endangered species.

It is very hard for a small population like the vaquita to recover. This is partly because we don't know enough about how they reproduce.

Efforts to Save the Vaquita

The vaquita is only found in the upper Gulf of California, Mexico. Its small population size puts it at high risk of extinction. Human activities, like accidental catches in fishing nets and illegal fishing, have caused their decline. Shrimp fishing and gillnets are big problems for vaquitas.

The Mexican government, international groups, scientists, and conservation organizations are working together. They have made plans to reduce accidental catches and enforce gillnet bans. They also want to help the population recover.

In 2017, Mexico made it a serious crime to remove an endangered species. They also agreed to ban gillnet use. Programs have been set up to help fishermen switch to safer fishing gear. They also offer money to fishermen who give up their fishing permits.

However, illegal fishing continues. The swim bladders of the Totoaba macdonaldi fish are sold illegally. This black market is very profitable, especially in China. Poachers can earn a lot of money from these sales.

Some vaquitas were briefly moved to protected sea pens in 2017. This was an effort called VaquitaCPR. Two vaquitas were captured, but one died shortly after due to shock. The other was released.

Local and international groups, like Museo de Ballena and Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, are working with the Mexican Navy. They try to find illegal fishing and remove gillnets. In March 2020, the U.S. banned imported Mexican shrimp and seafood caught in vaquita habitat.

Earth League International (ELI) has investigated the illegal totoaba trade. Their work helped Mexican authorities make important arrests in November 2020.

Saving the vaquita is a complex problem. It needs habitat protection, careful management of resources, education, and strong enforcement of fishing rules. It also needs new ways for fishermen to earn a living. Raising awareness about the vaquita is also very important.

In 2007, some experts said that breeding vaquitas in captivity was not a good option.

In July 2022, the Mexican government placed 193 concrete blocks in the Gulf of California. These blocks are meant to detect nets using sonar. They also aim to prevent vaquitas from getting trapped.

Creating protected areas is a common conservation method. For the vaquita, creating "buffer zones" near the coast could help. These zones would limit harmful pesticides. This would make the vaquita's home safer.

In May 2023, a survey found that the vaquita population had stabilized since 2021. This was a hopeful sign.

In October 2024, Colossal Biosciences announced plans to help the vaquita. They want to collect genetic material to potentially bring the species back if it becomes extinct. They also plan to use acoustic sensors and drones to monitor vaquitas. They will work with CONANP on these efforts.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Vaquita marina para niños

In Spanish: Vaquita marina para niños