Polhill Anglo-Saxon cemetery facts for kids

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Established | 7th century CE |

|---|---|

| Location | Polhill, Kent |

| Type | Anglo-Saxon inhumation cemetery |

The Polhill Anglo-Saxon cemetery is an ancient burial ground. It was used by people living in England during the 7th and 8th centuries CE. This cemetery is located near a small place called Polhill, close to Sevenoaks in Kent, South-East England. It is a very old site from the Middle Anglo-Saxon period. It shows us how people were buried a long time ago in Early Anglo-Saxon England.

At Polhill, people were only buried, not cremated (burned). Experts believe there were about 180 to 200 graves here. These graves held between 200 and 220 people. The cemetery was on a hill, giving it wide views of the land around it. It covered an area of about 1 hectare (2½ acres). Many of the people buried here had special items placed with them. These items included jewelry, weapons, and things used at home. Some graves even had small mounds of earth, called tumuli, built over them.

People first found graves at Polhill between 1839 and 1964. This happened while roads were being built. Later, archaeologists started digging carefully. Brian Philp led these digs in 1967 and 1978. In 1984, he led another big dig. This was because the M25 motorway was being expanded.

Contents

Where is Polhill Cemetery?

The Polhill cemetery is on the lower part of Polhill, in a place called Dunton Green. This is near Sevenoaks in Kent. The ground here is made of hard chalk. The cemetery sits where the Darent Valley meets the North Downs.

It is on a hill that looks out over a valley almost 3 kilometers wide. You can also see up the valley to the north and along the hills to the south-west. Brian Philp, who led the digs, thought this spot was very important. He believed it allowed the "ancestors" to be buried in a "very dominant" place. This way, they could watch over the land.

The village of Otford is about 2 kilometers east of the cemetery. You can see the cemetery from the center of Otford. Philp thought that Otford was probably the Anglo-Saxon village where the people who used Polhill cemetery lived.

A Look Back: Anglo-Saxon Kent

The Anglo-Saxon period began in the 5th century CE. During this time, the area that became Kent changed a lot. Before this, it was part of the Roman Empire. But after Roman rule ended around 410 CE, many Roman ways disappeared. New Anglo-Saxon customs took their place.

Old stories say that tribes from northern Europe came to England. These tribes were the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. They spoke Germanic languages. But archaeologists have found that Anglo-Saxon culture also mixed with the old Roman-British culture.

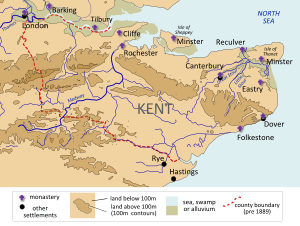

The name Kent first appeared in the Anglo-Saxon period. It came from an older Celtic name, Cantii. At first, it only meant the area east of the River Medway. But by the end of the 6th century, it included areas to the west too. The Kingdom of Kent was the first Anglo-Saxon kingdom we know about. It became very powerful by the late 500s. It controlled many parts of southern and eastern Britain.

Kent traded a lot with Francia (modern-day France). The royal family of Kent also married members of Francia's Merovingian dynasty. These French rulers were already Christian. Kentish King Æthelberht was a powerful ruler. He became Christian in the early 7th century. This happened because Augustine of Canterbury and the Gregorian mission came to England. They were sent by Pope Gregory to bring Christianity. The Polhill cemetery was used during this important time.

Kent has many old burial sites from the Early Medieval period. People started digging up Anglo-Saxon graves in Kent in the 17th century. These early diggers were called antiquarians. They were very interested in old objects. Over time, these early interests led to more careful archaeological digs. Famous archaeologists like Bryan Faussett and Charles Roach Smith studied Kent's past.

What the Cemetery Looks Like

The digs in 1984–86 showed that the cemetery had clear edges. Even though there was a lot of hillside, all the burials were in a specific area. Only bodies were buried here; no one was cremated. Archaeologists found 73 graves in the west, 52 in the east, and 4 outside the main area. They think about 53 more were in the middle. This means there were around 182 graves in total.

Brian Philp thought there might be between 180 and 220 graves. These graves held between 200 and 220 people. If the cemetery was used for about 100 years (from 650 to 750 CE), that means about two people were buried there each year. People at that time lived to about 26 years old on average. So, Philp guessed the cemetery served a community of 70 to 90 people. This would make it the largest known community in West Kent during that time.

Most of the bones were well preserved. This is because the chalk ground drained water away well. But some bones, especially those of children, had almost disappeared. The 1984–86 dig found 4 infants buried with 48 young people and adults. This number does not show how many babies actually died in those communities.

The main cemetery is about 210 meters long from west to east. It is about 50 meters wide from north to south. Its total area is about 10,500 square meters, or 1 hectare. The graves were not spread out evenly. They were often grouped together. Brian Philp thought these groups might be family units. Most burials were on the southern side. The west side of the cemetery was more crowded than the east.

From the 1984–86 dig, 50 graves had one skeleton. Only Grave 19 had two people buried together. Like many Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, most burials faced roughly east to west. Philp noted that 66% of the 51 burials from 1984–86 faced between 70 and 109 degrees.

Out of 51 burials dug up in the 1980s, 36 had grave goods. Grave goods are items buried with the person. Fourteen graves had no items. One grave was partly destroyed, so archaeologists don't know if it had items. About 140 items were found in this dig. Most were personal ornaments, weapons, or household items. Philp believed that graves with spearheads, seaxes (a type of knife), or shields belonged to important people. Only one grave, called Grave 1, had a shield. It also had a spear. This grave was at the far east of the cemetery, which Philp thought was very meaningful.

Eight of the 51 burials from 1984–86 were surrounded by small circular ditches. This means they were probably covered by small mounds called tumuli. Six more tumuli were found in the 1967 dig. So, there were at least 14 tumuli at the cemetery. It's possible other burials also had mounds, but they might have been worn away by farming over the centuries. The known mounds were spread out. They were between 4 and 5½ meters wide. Most had an entrance on the east side. Most mounds covered one person. But one mound covered two graves (94 and 95), and another had no burial at all. Of the 14 people buried under these mounds, 5 were male, 5 were female, 1 was an adult whose gender is unknown, and 3 were children.

How We Found Out About Polhill

Graves in the middle of the cemetery were found bit by bit between 1839 and 1964. This happened as a road was built and made bigger through the cemetery. The first discovery of bones was likely in 1839. This was when the Sevenoaks Turnpike Road was changed. No burials were officially written down then. But stories of bones and weapons being found were passed down.

In June 1956, the A26 was being worked on. This led to finding 13 more graves. In 1956 and 1958, the Otford Historical Society tried to dig nearby. They hoped to find more of the cemetery, but they missed the burial area. In August 1959, another road project found 3 more graves. In November 1959 and January 1960, schoolboys digging in the chalk found two more. Around 1963, workers building a small water tank found another grave. This one was not recorded.

In October 1964, work started on the Sevenoaks Bypass. This affected the cemetery. A wide strip of ground was removed on the west side of the road. This revealed one grave and might have destroyed others. The construction company told the Kent County Council. They contacted archaeologist Brian Philp through Maidstone Museum. Philp started a six-day emergency dig. His team dug up and recorded 14 graves. They also found 2 more in a pipe trench.

In November 1966, more construction found more graves. This time they were on the east side of the A21. Since more building was planned, Philp and his team started a large dig. They worked on the western end of the cemetery. They found 68 graves and a small hut. In 1978, they found four more graves in a separate group to the west.

In 1982, it was found that the M25 motorway would be extended. This extension would cross the east side of the cemetery. The Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit (KARU) was hired to study the area before construction. They dug up an area of 2500 square meters in March and April 1984. They found 50 more burials. Brian Philp led this project again. He had 54 other archaeologists helping him. These helpers were from different community groups.

Another burial was found nearby in 1986. The bones found were studied by Elizabeth Rega from the University of Sheffield. Her study was paid for by a grant in 1993. Most of the work after the dig was paid for by a donation from Diana Briscoe. The results of these 1980s digs were written by Philp and published in 2002. Archaeologist Martin Welch said that Polhill was the most completely published cemetery from the 7th and early 8th centuries in Kent for a long time.