Proto-Semitic language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Proto-Semitic |

|

|---|---|

| Reconstruction of | Semitic languages |

| Era | ca. 4500–3500 BC |

|

Reconstructed

ancestor |

Proto-Afroasiatic

|

| Lower-order reconstructions |

|

Proto-Semitic is the name for a very old, reconstructed language. It's like the "grandparent" language from which all Semitic languages (like Arabic, Hebrew, and Aramaic) grew. We don't have any written records of Proto-Semitic itself, but language experts called linguists have pieced it together by studying its "daughter" languages.

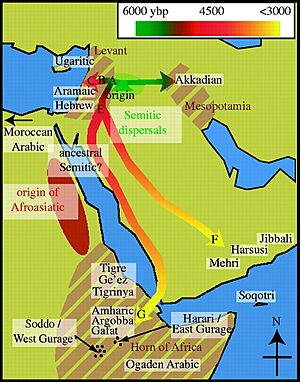

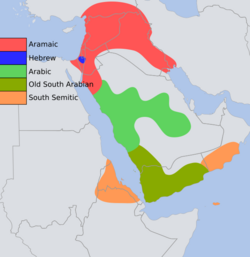

Scientists aren't sure exactly where Proto-Semitic was first spoken. They call this original home the Urheimat. Some think it was in the Levant (the area around modern-day Israel, Lebanon, and Syria), others suggest the Sahara desert, the Horn of Africa, or the Arabian Peninsula.

The Semitic language family is part of an even bigger group of languages called Afroasiatic languages.

Contents

When Was Proto-Semitic Spoken?

The earliest writings we have from any Semitic language are in Akkadian, which appeared around 2400-2300 BC. We also have texts from the Eblaite language from a similar time. Even before that, some Akkadian names show up in older Sumerian writings.

For example, one of the first known Akkadian writings was found on a bowl in a city called Ur. It was for a king named Meskiagnunna, who lived around 2485–2450 BC. The earliest writings from West Semitic languages (another branch) are ancient Egyptian spells from around 2500 BC.

Since Proto-Semitic came before these languages, it must have been spoken even earlier. Experts believe it was used sometime in the fourth millennium BC (between 4000 and 3000 BC) or even before that. This would give enough time for the language to change and develop into Akkadian and other early Semitic languages.

Where Did Proto-Semitic Come From?

Since all modern Semitic languages come from Proto-Semitic, language experts have tried to find its original home, or Urheimat. Thinking about the larger Afroasiatic language family, which Semitic belongs to, can help with this search.

One idea was that Proto-Semitic came from the Arabian Peninsula. However, this idea has mostly been dropped. The region probably couldn't have supported large groups of people moving out until camels were tamed around 2000 BC.

There's also evidence that areas like Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) and parts of Syria were originally home to people who didn't speak Semitic languages. This is suggested by old place names in Akkadian and Eblaite that are not Semitic.

The Levant Idea

A study in 2009 used a special computer analysis to suggest that all known Semitic languages started in the Levant around 3750 BC. It also suggested that people speaking a Semitic language later moved from South Arabia to the Horn of Africa around 800 BC. This study couldn't say when or where Proto-Semitic first split off from the larger Afroasiatic family. So, it doesn't prove or disprove the idea that Proto-Semitic started in Africa.

Another idea is that the first group of Proto-Semitic speakers entered the Fertile Crescent (a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East) through the Levant. They eventually founded the Akkadian Empire. Their relatives, the Amorites, followed them and settled in Syria before 2500 BC. Later, during a time of trouble called the Late Bronze Age collapse in Israel, the South Semites moved south. They settled in the highlands of Yemen after 2000 BC. From there, some crossed the Bab el-Mandeb strait to the Horn of Africa between 1500 and 500 BC.

How Proto-Semitic Sounded

Vowels

Proto-Semitic had a simple vowel system. It had three basic vowel sounds: *a, *i, and *u. These vowels could also be long, like *ā, *ī, and *ū. This system is still found in Classical Arabic, a very old form of Arabic.

Consonants

When linguists try to figure out what Proto-Semitic sounded like, they often look at Arabic. Classical Arabic is very good at keeping old sounds and word structures. It has 28 of the 29 consonant sounds that Proto-Semitic is thought to have had.

Proto-Semitic is believed to have had special groups of three related consonants:

- Stops: Sounds like *d, *t, and *ṭ (a "stronger" t sound).

- Sibilants: Sounds like *z, *s, and *ṣ (a "stronger" s sound).

- Interdentals: Sounds like *ḏ, *ṯ, and *ṯ̣ (like 'th' in English "this" or "thin," plus a "stronger" th sound).

- Laterals: Sounds like *l, *ś, and *ṣ́ (sounds made with the side of the tongue, including "stronger" versions).

Many of these sounds are straightforward. However, the "emphatic" consonants (like *ṭ, *ṣ, *ṯ̣, *ṣ́) are special. In modern Semitic languages, these can sound "pharyngealized" (made with the back of the throat, like in Arabic) or "glottalized" (made with a quick stop of air in the throat, like in some Ethiopian languages).

How Proto-Semitic Words Were Built

Nouns

Proto-Semitic nouns had different endings depending on their role in a sentence. These are called "cases":

- Nominative: Used for the subject of a sentence (ending in `*-u`).

- Genitive: Used to show possession (ending in `*-i`).

- Accusative: Used for the direct object (ending in `*-a`).

Nouns also had two genders:

- Masculine: Had no special ending.

- Feminine: Often ended with `*-at` or `*-t`, or sometimes `*-ah` or `*-ā`. For example, `*ba‘l-` (lord) became `*ba‘lat-` (lady).

There were three ways to show how many of something there were:

- Singular: For one item.

- Plural: For more than one item.

- Dual: For exactly two items.

Plurals could be formed in two ways:

- Adding endings: Masculine nouns might add `*-ū` (nominative) or `*-ī` (genitive/accusative). Feminine nouns added `*-āt`.

- Changing vowels: Some masculine nouns changed their inner vowels, like in Arabic where kātib (writer) becomes kuttāb (writers).

The dual form used `*-ā` for nominative and `*-āy` for genitive and accusative.

Pronouns

Proto-Semitic had words like "I," "you," "he," etc. (called pronouns). These could be stand-alone words or small endings attached to other words. For example, "I" was `ʼanā̆` or `ʼanākū̆`.

Numbers

Here are some reconstructed numbers from Proto-Semitic:

- One: `*’aḥad-`

- Two: `*ṯinān`

- Three: `*śalāṯ-`

- Four: `*’arbaʻ-`

- Five: `*ḫamš-`

- Six: `*šidṯ-`

- Seven: `*šabʻ-`

- Eight: `*ṯamāniy-`

- Nine: `*tišʻ-`

- Ten: `*ʻaśr-`

Numbers from one to ten acted like singular nouns, except for "two," which acted like a dual noun. To make feminine numbers, the suffix `*-at` was added. Interestingly, for numbers 3 to 10, if you were counting feminine things, you used the masculine form of the number, and vice versa!

Numbers like 11 to 19 were made by combining the unit number with "ten." "Twenty" was the dual form of "ten." Numbers like 30, 40, etc., were plural forms of 3, 4, etc. Proto-Semitic also had words for hundred (`*mi’t-`), thousand (`*li’m-`), and ten thousand (`*ribb-`).

Verbs

Proto-Semitic verbs had two main forms:

- Prefix conjugation: The verb changed by adding prefixes (like `*’a-` for "I" or `*yi-` for "he"). This was used for actions.

- Suffix conjugation: The verb changed by adding suffixes (like `*-ku` for "I" or `*-at` for "she"). This was used for states or conditions.

Most verb roots had three consonants. For example, to make a verb, vowels were placed between these three consonants.

The "imperative mood" (commands) was only for the second person ("you"). For a singular masculine command, it was just the basic verb root.

Connecting Words (Conjunctions)

Three main connecting words are thought to have existed in Proto-Semitic:

- `*wa` meaning 'and'

- `*’aw` meaning 'or'

- `*šimmā` meaning 'if'

Sentence Structure (Syntax)

Proto-Semitic was a nominative-accusative alignment language. This means the subject of a sentence (who or what is doing the action) and the object (who or what is receiving the action) were marked differently. Most Semitic languages today still work this way.

The basic word order in Proto-Semitic was VSO (Verb - Subject - Object). For example, instead of "The boy ate the apple," it would be "Ate the boy the apple." Also, describing words usually came after the thing they described.

Proto-Semitic Vocabulary

By reconstructing Proto-Semitic words, we can learn more about how the people who spoke it lived. This also helps in the search for their original homeland.

Here are some examples of words that have been reconstructed:

- Religious words: `*’il` 'deity' (god), `*ḏbḥ` 'to perform a sacrifice', `*ḳdš` 'be holy', `*ḥrm` 'to forbid'.

- Farming words: `*ḥaḳl-` 'field', `*ḥrṯ` 'to plough', `*zrʻ` 'to sow', `*ʻṣ́d` 'to harvest', `*ḥinṭ-` 'wheat', `*duḫn-` 'millet'.

- Animal words: `*’immar-` 'ram', `*raḫil-` 'ewe' (female sheep), `*‘inz-` 'goat', `*’alp-` 'bull', `*ṯawr-` 'buffalo', `*ḫzr-` or `*ḫnzr-` 'pig', `*kalb-` 'dog', `*ḥimār-` 'donkey', `*ḥalab-` 'milk'.

- Daily life words: `*bayt-` 'house', `*dalt-` 'door', `*kussi’-` 'chair', `*bi’r-` 'well', `*’iš-` 'fire', `*laḥm-` 'food'.

- Technology words: `*ṣrp` 'to smelt' (melt metal), `*kasp-` 'silver', `*ḥabl-` 'rope', `*ḳašt-` 'bow' (for shooting arrows), `*ḥaṱw-` 'arrow'.

- Plants and foods: `*ti’n-` 'fig', `*ṯūm-` 'garlic', `*baṣal-` 'onion', `*tam(a)r-` 'palm tree', `*kammūn-` 'cumin'.

Some words, like `*ṯawr-` 'buffalo' and `*ḳarn-` 'horn', might have been borrowed from another ancient language family called Proto-Indo-European, or vice versa. Some experts believe there were many words borrowed between Proto-Semitic and early Indo-European languages.

See also

- Afroasiatic languages

- Afroasiatic homeland

- Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples

- History of the Middle East

- Proto-Afroasiatic language

- Proto-Indo-European language

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |