Rafael Alberti facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rafael Alberti

|

|

|---|---|

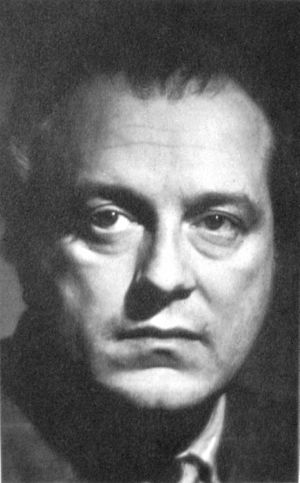

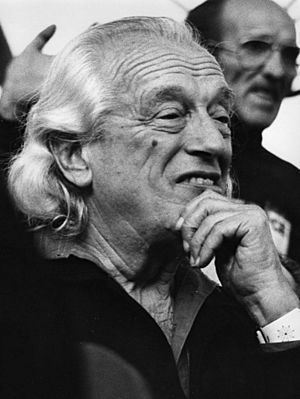

Andalusian poet Rafael Alberti in Casa de Campo (Madrid), 1978

|

|

| Born | 16 December 1902 El Puerto de Santa María, Cádiz, Kingdom of Spain |

| Died | 28 October 1999 (aged 96) El Puerto de Santa María, Cádiz, Spain |

| Spouse | |

Rafael Alberti Merello (born December 16, 1902 – died October 28, 1999) was a famous Spanish poet. He was part of a special group of writers called the Generation of '27. Many people think he was one of the most important writers of Spain's "Silver Age" of Spanish Literature. He won many awards for his work. Rafael Alberti lived to be 96 years old.

After the Spanish Civil War, he had to leave Spain because of his strong political beliefs. When he returned to Spain after Franco died, he received special honors. In 1983, he was named a "Favorite Son of Andalusia," and in 1985, he received an honorary degree from the Universidad de Cádiz.

He wrote a book about his life called La Arboleda perdida (which means 'The Lost Grove') in 1959. This book is a great way to learn about his early years.

Contents

Life Story of Rafael Alberti

Growing Up in Spain

Rafael Alberti was born in 1902 in El Puerto de Santa María, a town near the Guadalete River in Cádiz. His family used to be very powerful wine producers, selling sherry to kings and queens across Europe. However, due to some problems, their family business was sold.

Because of this, Rafael's father worked as a traveling salesman. This feeling of his family's past greatness and current decline became a common idea in his later poems.

When he was 10, Rafael went to a Jesuit school called Colegio San Luis Gonzaga. At first, he was a good student. But he soon noticed that some students were treated differently than others. This made him want to rebel. He started skipping school and challenging the teachers. In 1917, he was finally expelled. Luckily, his family was moving to Madrid at that time, so the expulsion wasn't as big a deal.

In May 1917, his family moved to Madrid. By then, Rafael was already very interested in painting. In Madrid, he didn't focus on school. Instead, he spent many hours at art museums like the Casón del Buen Retiro and the Prado. He copied famous paintings and sculptures. He even showed his paintings in an art show in Madrid in 1920. However, after his father and some other famous people died in 1920, he felt inspired to start writing poetry.

Life as a Young Poet in Madrid

In 1921, Rafael became sick with tuberculosis. He spent many months recovering in a special hospital in the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains. During this time, he read a lot of books by famous Spanish writers like Antonio Machado and Juan Ramón Jiménez. He also read works by new, modern writers.

He met Dámaso Alonso, who was a poet at the time. Dámaso introduced Rafael to older, classic Spanish writers. Rafael started writing poetry seriously and sent some of his poems to new magazines. His first book of poems, Marinero en tierra (meaning 'Sailor on Dry Land'), won the important National Poetry Award in 1925.

For the next few years, Rafael became well-known in the art world, though he still relied on his family for money. New literary magazines were eager to publish his poems. He also started making friends with other young writers who would later form the "Generation of '27." He met Vicente Aleixandre and, around 1924, Federico García Lorca at the Residencia de Estudiantes. Although they weren't best friends, Rafael wrote a poem for Lorca after he died in 1936. At the Residencia, he also met other famous artists and writers like Pedro Salinas, Jorge Guillén, Gerardo Diego, Luis Buñuel, and Salvador Dalí.

His early poems in Marinero used a traditional, song-like style. He continued this style in two more collections: La amante ('The Mistress') and El alba del alhelí ('Dawn of the Wallflower'). But as a special event for the poet Luis de Góngora approached, Rafael started writing in a more complex and dramatic way. This led to his book Cal y canto (‘Quicklime and Plainsong’).

Soon after, Rafael began writing poems for Sobre los ángeles (‘Concerning the Angels’). This book was a big change in his poetry and is often seen as his best work. His next books, Sermones y moradas (‘Sermons and mansions‘) and Yo era un tonto y lo que he visto me ha hecho dos tontos (‘I was a fool and what I have seen has made me two fools’), along with a play called El hombre deshabitado (‘The Empty Man’), showed he was going through a difficult time. He found relief when he married the writer and activist María Teresa León around 1929 or 1930.

Marriage, Politics, and Exile

His marriage to María Teresa León, along with his memories of school, helped turn Rafael into a strong supporter of Communism in the 1930s. When the Second Spanish Republic was formed in 1931, it also pushed him towards these beliefs, and he joined the Communist Party of Spain. For Rafael, this political belief became very important, almost like a religion.

As a representative for the Party, he no longer needed his family's financial help. He traveled to many countries in northern Europe. But when Gil Robles came to power in 1933, Rafael wrote very strong criticisms against him in a magazine called Octubre (‘October’), which he started with María Teresa. This led to a period where he had to live outside Spain.

When the Spanish Civil War began in July 1936, Rafael was in Ibiza. He was released in August 1936 when the island came under Republican control. By November 1936, he was in Madrid. He used a large house near Retiro Park as the main office for his Alliance of Anti-Fascist Intellectuals.

During the Spanish Civil War, Rafael became a poetic voice for the Republican side. He often broadcast from Madrid during the Siege of Madrid by the Francoist armies, writing poems praising the city's defenders. He published these poems in a magazine called El Mono Azul, which he co-founded with his wife. His poems also appeared in the newspaper for the XV International Brigade.

In early 1939, after the defeat of the Republican forces, Rafael and María fled to Paris. They lived there until the end of 1940, working as translators and announcers for French radio. After the German occupation of France, they sailed from Marseilles to Buenos Aires, Argentina.

They lived in Argentina until 1963. Rafael continued to write and paint, and he also worked in the Argentinian film industry. For example, he adapted a play called La dama duende (‘The Ghost Lady’) in 1945. After Argentina, they moved to Rome, Italy.

On April 27, 1977, Rafael and María Teresa finally returned to Spain. Soon after, Rafael was elected as a representative for Cádiz in the Spanish parliament, representing the Communist Party. His wife, María Teresa, passed away on December 13, 1988, from Alzheimer's disease.

Rafael Alberti died at the age of 96 from a lung illness. His ashes were scattered over the Bay of Cádiz, the place he loved most.

Awards and Honors

Rafael Alberti received many important awards for his work.

- He was given the Lenin Peace Prize in 1964.

- In 1981, he received the Laureate Of The International Botev Prize.

- In 1983, he won the Premio Cervantes, which is the highest literary honor in the Spanish-speaking world.

- In 1998, he received the America Award in Literature for his contributions to writing around the world.

Rafael Alberti's Poetry

Early Poems

Rafael Alberti's first well-known book was Marinero en tierra ('Sailor on Dry Land'). This book showed many different influences. It had the style of old Spanish songs and medieval poems. It also had a more formal, complex style, and some modern ideas. Rafael seemed to write poetry very easily, and his poems often had a feeling of innocence, even though they were carefully put together.

Marinero en tierra explores two important themes that would appear throughout his work: his love for the sea where he grew up and his longing for his childhood. The poems in this part of the collection often have lines of different lengths and a musical quality, like traditional songs.

He quickly followed with La amante (1925) and El alba del alhelí (1926). These early works were inspired by traditional songs and local stories. In La amante, he imagined a girlfriend and wrote lighthearted poems about the places they saw. El alba was written during holidays with his sisters.

Developing His Style

His next collection, Cal y canto (1926-8), was a big change. He moved away from some of the folk influences and returned to more formal styles, like sonnets. He also included modern themes. Rafael was in charge of collecting poems for a celebration of the poet Góngora, and Góngora's influence can be seen in this book.

Rafael showed how skilled he was at different poetry forms. There's also a feeling of unease in this collection. Old traditions and new modern ideas like speed and freedom are explored, but they all seem to fall short. He even wrote a poem about a heroic soccer goalkeeper, "Oda a Platko", showing how modern life was entering his poetry.

The last poem in Cal y canto, "Carta abierta" (‘Open Letter’), is very important. In it, Rafael writes as himself, a person from Cádiz in the 20th century. He compares the strictness of school with the freedom of the seashore. He contrasts the boredom of lessons with the excitement of cinema. He also compares old literature with the new world of radio, airplanes, and telephones. In this mix of old and new, the poet felt a sense of emptiness, but he decided to embrace the new.

Sobre los ángeles and Later Works

Building on the feeling of unease from Cal y canto, Rafael began to explore deep, sad feelings. He felt he had lost his youthful happiness and felt "empty." He wondered how he could express these strong emotions. He felt like he was falling apart inside.

Then, he had a kind of "angelic revelation." These weren't the angels from paintings, but powerful spirits that matched his darkest thoughts. He felt like he was releasing all the cruelty, sadness, and even goodness that was inside him and around him. He felt he had lost a "paradise," the innocence of his early years.

The first part of Sobre los ángeles (1927-8) is mostly about losing love and feeling empty. The lines are short and have a musical flow. The middle part explores a feeling of being let down by religion. Even though his childhood beliefs were challenged early on, he still needed something to believe in to feel less empty. The last part of the book changes style completely, with much longer lines and complex, dream-like images. This style continued in his next few works.

Yo era un tonto y lo que he visto me ha hecho dos tontos (1929) was Rafael's tribute to the American silent movie comedians he loved, like Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd. Even though the poems were inspired by funny movies, they were still written in his complex style.

His final work in this style was Con los zapatos puestos tengo que morir ('With My Shoes On I Must Die') (1930). This book, while still complex, started to show his growing interest in social issues and politics.

Poetry of the 1930s

During the 1930s, Rafael's political commitment became very clear in his poetry. He wrote poems that supported his political party, showing his technical skill. He also wrote more personal poems, using his memories to criticize opposing forces in a direct way.

De un momento a otro (‘From One Moment to the Next’) (1932-8) includes a poem called "Colegio (S.J.)" that again looks back at his school days. This time, he analyzes how the Jesuits treated students differently, showing his new understanding of social classes.

In 13 bandas y 48 estrellas (’13 Stripes and 48 Stars’) (1935), Rafael wrote about his travels to the Caribbean and the United States. These trips gave him many ideas for poems that discussed social and economic systems.

Capital de la gloria (‘Capital of Glory’) (1936-8) collects the poems he wrote during the Siege of Madrid in the Spanish Civil War. These poems honored Republican generals and the International Brigades. He also wrote about the peasant-soldiers. This collection shows a return to more structured poem forms.

Entre el clavel y la espada (‘Between the Carnation and the Sword’) (1939–40) gathers poems Rafael wrote in France and Argentina at the start of his long time in exile. This book shows a change in his style, as he aimed for more discipline in his poetry. It uses formal approaches similar to Marinero en tierra. A key theme in this collection is his deep and lasting longing for Spain, the country he had to leave.

Later Works and Themes

A la pintura (‘On Painting’) (1945- ) is a series of poems Rafael started writing during his exile, when he began painting again. He continued adding to this collection for many years. He wrote sonnets about painting tools like the retina, hand, canvas, and brush. He also wrote short poems about colors and honored famous painters like Titian and El Greco.

Ora Maritima (‘Maritime Shore’) (1953) is a collection dedicated to Cádiz, his hometown. The poems explore the city's ancient history and myths, like Hercules and the Carthaginians. They also bring in his childhood memories of the bay.

Retornos de lo vivo lejano (‘Memories of the Living Distance’’) (1948-52) and Baladas y canciones de la Paraná (‘Ballads and Songs of the Paraná’) (1955) are collections of lyrical poems about memory and nostalgia. He remembered his school days with sadness. He also recalled his mother, his friends (especially Vicente Aleixandre), the death of Lorca, and wrote a touching tribute to his wife.

Other Creative Works

Rafael Alberti wasn't mainly a playwright, but he made a big impact with at least two plays. One was El hombre deshabitado ('The Empty Man', 1930), which explored his feelings of emptiness. It had characters like Man with his Five Senses, The Maker, and Temptation. When it opened, the audience had very strong, mixed reactions.

Soon after, he wrote a play about Fermín Galán, an army captain who tried to start a Spanish Republic in 1930 and was executed. This play was performed in June 1931 and also received mixed reactions.

His other plays include De un momento a otro ('From One Moment to Another', 1938–39), El trébol florido ('Clover', 1940), El adefesio ('The Disaster', 1944), and Noche de guerra en el Museo del Prado ('A Night of War in the Prado Museum', 1956). He also wrote adaptations and shorter pieces.

Rafael Alberti also wrote several books of memoirs called La arboleda perdida ('The Lost Grove').

Poetry Collections List

- Marinero en tierra, 1925 (National Literature Award).

- La amante, 1926.

- El alba de alhelí, 1927.

- Cal y canto, 1929.

- Yo era un tonto y lo que he visto me ha hecho dos tontos, 1929.

- Sobre los ángeles, 1929.

- El poeta en la calle (1931–1935), 1978.

- Consignas, 1933.

- Un fantasma recorre Europa, 1933.

- Poesía (1924–1930), 1935.

- Versos de agitación, 1935.

- Verte y no verte. A Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, 1935.

- 13 bandas y 48 estrellas. Poemas del mar Caribe, 1936.

- Nuestra diaria palabra, 1936.

- De un momento a otro (Poesía e historia), 1937.

- El burro explosivo, 1938.

- Poesías (1924–1937), 1938.

- Poesías (1924–1938), 1940.

- Entre el clavel y la espada (1939-1940), 1941.

- Pleamar (1942–1944), 1944.

- Poesía (1924–1944), 1946.

- A la pintura, 1945.

- A la pintura. Poema del color y la línea (1945–1948), 1948.

- Coplas de Juan Panadero. (Libro I), 1949.

- Poemas de Punta del Este (1945–1956), 1979.

- Buenos Aires en tinta china, 1952.

- Retornos de lo vivo lejano, 1952.

- A la pintura (1945–1952) 2nd augmented edition, 1953.

- Ora marítima seguido de Baladas y canciones del Paraná (1953), 1953.

- Balada y canciones del Paraná, 1954.

- Sonríe China, 1958 (with María Teresa León).

- Poemas escénicos, 1962.

- Abierto a todas horas, 1964.

- El poeta en la calle (1931–1965), 1966.

- Il mattatore, 1966.

- A la pintura. Poema del color y la línea (1945–1967) 3rd augmented edition, 1968.

- Roma, peligro para caminantes, 1968.

- Los 8 nombres de Picasso y no digo más que lo que no digo, 1970.

- Canciones del Alto Valle del Aniene, 1972.

- Disprezzo e meraviglia (Desprecio y maravilla), 1972.

- Maravillas con variaciones acrósticas en el jardín de Miró, 1975.

- Casi Malagueñas de la Menina II, 1976.

- Coplas de Juan Panadero (1949–1977), 1977.

- Cuaderno de Rute (1925), 1977.

- Los 5 destacagados, 1978.

- Fustigada luz, 1980.

- Versos sueltos de cada día, 1982.

- Golfo de Sombras, 1986.

- Los hijos del drago y otros poemas, 1986.

- Accidente. Poemas del Hospital, 1987.

- Cuatro canciones, 1987.

- El aburrimiento, 1988.

- Canciones para Altair, 1989.

Rafael Alberti's Legacy

- There is a bookstore named Rafael Alberti in the center of Madrid, which opened in 1975.

- A museum and foundation dedicated to Rafael Alberti operates in his hometown of El Puerto de Santa María, Cádiz.

- In the book Yo-Yo Boing! (1998) by Giannina Braschi, there is a discussion about great Spanish and Latin American poets. Rafael Alberti is mentioned as one of the masters of poetry, alongside Vicente Aleixandre, Vicente Huidobro, Pedro Salinas, and Jorge Guillén.

See also

In Spanish: Rafael Alberti para niños

In Spanish: Rafael Alberti para niños

- Museo Fundación Rafael Alberti

- Spanish poetry