Riotinto-Nerva mining basin facts for kids

The Riotinto-Nerva mining basin is a mining area in Spain. It is located in the northeast part of the province of Huelva in Andalusia. The main towns in this area are El Campillo, Minas de Riotinto, and Nerva. This region is also part of the Iberian Pyrite Belt, which is a large area rich in minerals.

People have been mining in this area for a very long time, even before recorded history. However, it was during the time of the Romans that mining became very organized and important. After a break, mining started again in the Modern Age. The Riotinto basin was most active between the late 1800s and mid-1900s. During this time, a British company called Rio Tinto Company Limited managed the mines. This led to a big increase in industry and population. Today, mining still happens, mostly at Cerro Colorado, but not as much as in the past.

The basin has a rich history and many old industrial buildings. These are from the time when mining was at its peak, especially during the British period. Because of this, efforts have been made in recent years to protect these sites and use them for tourism. In 2005, the Riotinto-Nerva mining area was named a Bien de Interés Cultural (a site of cultural interest) because of its historical importance.

Contents

What Makes It Special?

The Riotinto-Nerva mining basin is in the northeast of the province of Huelva. It sits about 418 meters above sea level. This area covers about 170 square kilometers. Like other mining spots in southwestern Spain, Riotinto-Nerva is part of the Iberian Pyrite Belt. This means it has a lot of pyrite and chalcopyrite. These are minerals used in many industries. The mining area is in a low mountain landscape called the Andévalo, with gentle hills between 500 and 700 meters high. Over time, mining has greatly changed how this area looks.

The Riotinto mining complex had several large mineral deposits spread over 4 square kilometers. These held about 500 million tons of ore. The main deposits are called Filón Norte, Filón Sur, Masa Planes, Masa San Dionisio, and Masa San Antonio. The San Antonio deposit is in Nerva and is one of the newer ones, found in the second half of the 1900s. The Peña del Hierro deposit in Nerva was also very important.

A Look Back in Time

From Ancient Times to the Middle Ages

The Riotinto mines are known as one of the most important mining areas from ancient times. There is proof of mining here during the Copper Age and Bronze Age. But it became much more important centuries later. Tests show that a lot of mining was happening by at least 366 BC. The oldest signs of mining and human settlements are found in the Filón Norte area. Minerals might have been sent out in two ways: one path went to the Guadalquivir River through a difficult mountain road, and another went along the Tinto River.

Even though we don't have all the details, there is clear evidence that several mines in Riotinto were active during Roman times. Mining was at its busiest between 200 BC and 200 AD, especially after the rule of Augustus. The Romans dug many underground tunnels and used complex water wheels to remove water from the mines. Working conditions in these tunnels were very tough for the miners, who were mostly slaves. They faced dust, high humidity, poor light, and high temperatures. Studies show that silver was the most produced metal during the High Roman Empire. Riotinto was one of the best silver mines of that time. From the time of Augustus, copper mining also became very important.

The Romans built many structures to support mining and metalwork, like furnaces and foundries. They also built roads to help move goods. The area known today as Corta del Lago was the main Roman settlement. Ancient writings call this place Urion or Urium. There are also several burial sites (like Huerta de la Cana and La Dehesa) from the High Roman Empire. The Riotinto mines were active until the late 200s AD. At that time, other mines in places like Dacia and Britannia became more popular.

The metalwork done by the Romans left behind a lot of slag (waste material). This greatly changed the look of the land. Centuries later, much of this slag was reused for different purposes. Many Roman artifacts were found and saved from the 1800s onwards by British engineers. However, the first discoveries were made by Spaniards in the mid-1700s. During the medieval period, not much mining happened in Riotinto. In the Islamic era, most work focused on getting copper sulfates and iron sulfate.

Mining Starts Again in Modern Times

In the 1500s, during the reign of Philip II, people thought about reopening the Riotinto mines. The Spanish Crown owned these mines. But this plan was dropped in favor of the Guadalcanal mines in Seville, which seemed more promising. The mines in the Americas were also more interesting to the authorities. The Huelva mines were thought to be used up after the Romans had mined them so much.

In the early 1700s, interest in mining here grew again. In 1725, a Swede named Liebert Wolters Vonsiohielm was given permission by the Crown to mine in Riotinto for thirty years. Wolters first drained the old Roman tunnels. After he died in 1727, his nephew, Samuel Tiquet, and a Spanish partner took over. They focused on the Filón Sur deposit. After Tiquet's death, the Spanish partner, Francisco Thomas Sanz, managed the mines. Under his leadership, the mines produced a lot of minerals. Because of the mining, the town of Ríotinto was also founded during this time, next to Filón Sur.

The Riotinto mines were left empty and inactive during the War of Independence. This was due to the country's difficulties at that time. In 1823, after engineer Fausto Elhuyar visited the area, the mines were fixed up and work started again. Between 1829 and 1849, the marquis of Remisa leased the mines. Many problems happened during this period. After 1849, the Spanish Royal Treasury took back direct control. Because of the Industrial Revolution happening elsewhere, the Riotinto mines faced problems. They lacked modern tools and ways of working, which stopped them from mining well. However, in the mid-1800s, the Spanish government didn't have enough money to use its mining properties properly.

The British Era: The Busiest Years

By the mid-1800s, the Riotinto mines caught the eye of international investors. This was because the industrial growth in some European countries needed more raw materials. Since the Spanish government was in financial trouble, selling these mines had been considered. After the revolution of 1868 and the political changes that followed, minister Laureano Figuerola suggested selling the Riotinto mines to the Cortes (Spanish parliament) in March 1870. But it took several years for this to happen.

In 1873, the House of Rothschild bought the mines from the government of the First Republic. A few months later, they transferred ownership to the new British company, Rio Tinto Company Limited (RTC). The new owners started much more intense mining. At first, they focused on the "La Mina" deposit (or "Filón Sur"). By 1881, they had expanded operations to other parts of the area. Minerals like copper and pyrite were taken from Riotinto. RTC built many industrial facilities for processing the minerals. These included ore washing plants, factories, smelting (melting metal), and power plants. By the early 1900s, the Zarandas-Naya area became the main place for processing ore from the basin's deposits.

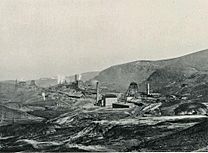

As mining grew, several main mining sites appeared in the basin. These included Corta Atalaya, Filón Sur, Filón Norte, and Corta Peña del Hierro. Some of these were large mining areas with several deposits. A big mining and industrial area also grew around the towns of Riotinto and Nerva. These towns became much larger and had more people during these years. Soon, the region became one of the most important mining areas in Spain. Also, under British management, the Riotinto mines became famous worldwide.

To make it easier to reach these mines and factories, the RTC built a narrow-gauge railroad. It opened in 1875 and had almost 360 kilometers of tracks, including the main line and many smaller branches. Minerals were also transported by this railway to the port of Huelva. From there, they were shipped to other countries. The heavy traffic led RTC to build a large ore storage area near Huelva, called "Polvorín".

The British kept using the old system of tunnels. But by the late 1800s, they started using open-pit mining, called "cortas". This allowed them to dig out much more mineral. This method helped create the large holes we see in the landscape today. While RTC was the main company in Riotinto, the Peña del Hierro mine was owned by several different companies, including The Peña Copper Mines Company Limited. This company had some disagreements with RTC at the time.

More mining and metalwork meant they needed more workers. This led to a huge increase in the local population. New worker settlements were built over the years, such as Alto de la Mesa, El Valle, La Atalaya, La Naya, Río Tinto-Estación, and La Dehesa. There was also a small group of British managers and engineers who lived in the Bellavista neighborhood. This was a residential area with victorian architecture where the English lived separately from the Spanish people. The town of Minas de Riotinto grew from 4,957 people in 1877 to 11,603 in 1900. Nerva also saw a big population increase during this mining boom, reaching 16,807 people by 1910.

Working conditions in the mining basin were "extremely harsh." This often led to disagreements between workers and RTC's British managers. Several big strikes happened between the late 1800s and early 1900s. The most important ones were in 1888, 1913, and 1920. The protests in 1888 were put down with violence by the police. This event is known as "the year of the shootings."

The 1920 strike was even bigger. It lasted nine months and involved about 11,000 workers. However, it did not achieve its goals. The punishments given by RTC after this strike stopped the workers' unions in the area for many years. They only started up again during the time of the Second Republic. In the 1930s, worker conflicts increased because of the economic crisis of 1929. In July 1936, when the Civil War began, the mining area was controlled by workers' committees on the "Republican Zone" side. But this didn't last long. A few weeks later, the rebel side took over the region with little resistance.

Spanish Control

In 1954, after a complicated process involving the Franco regime, the Rio Tinto mines were taken over by Spanish owners. They formed the Compañía Española de Minas de Río Tinto (CEMRT). Even though mining was already slowing down from the British period, it continued strongly under the new owners. CEMRT had bought four main deposits. Three of them (Filón Sur, Filón Norte, and Planes) were almost empty, and only one (San Dionisio) was still very active. Also, the mining and industrial equipment was old. The business mainly focused on exporting minerals. All this led to a new way of working. In the following years, the number of workers was adjusted, the facilities were updated, and mining became more mechanized.

Between 1960 and 1962, CEMRT explored the basin and found the San Antonio Mass in Nerva. This was mined through Pozo Rotilio. The exploration and mining of copper ore from Cerro Colorado were also started by the Río Tinto Patiño group, formed in 1966. The other deposits stayed under CEMRT's management. Their plans for growth led to the creation of the Unión Explosivos Río Tinto (ERT) group in 1970. From then on, the historic Corta Atalaya mine was expanded to get its large reserves of pyrites.

During this time, pyrite production was mostly for use within Spain. The amount of pyrites exported was much less. A lot of this pyrite went to factories built in the chemical park of Huelva. This park was created in 1964 to help the area's economy grow. Because of this, some industrial plants in Riotinto were taken apart and moved to the chemical park. Mining in the basin started to decline in the late 1970s. This was due to lower international copper prices and a mining crisis in Huelva.

Recent Times

In the 1980s, the ongoing poor economy led to big worker protests. Copper mining operations slowly stopped. Many worker demonstrations and two general strikes (in 1978 and 1986) happened during these years. Until the 1990s, the company Río Tinto Minera (RTM) was the main operator in the basin. But the industry's crisis eventually led to most facilities in the area closing down.

In 1984, as part of this situation, the Riotinto railroad service was stopped. From then on, transportation was done by trucks. In 1986, Pozo Alfredo closed, followed by Corta Atalaya in 1992. Only the mining of gossan (a type of iron ore) at Cerro Colorado was still active. After an unsuccessful attempt by RTM workers to restart the business, mining activities mostly stopped around 2001.

At the same time, in the 1980s, different ideas came up to protect the environment and historical sites of the mining basin, which were in danger of disappearing. Plans were made to create a Rio Tinto Mining Park for cultural, tourist, and fun purposes. They also planned a Riotinto Mining Museum and to save the historic Riotinto railway. A lot of important work has been done by the Rio Tinto Foundation. This group has helped restore many industrial heritage sites and set up the Tourist Mining Train.

In the early 2000s, there were several failed attempts to restart the mines, as copper prices went up. It wasn't until 2015 that the company Atalaya Mining from Cyprus restarted mining at Riotinto. They got the necessary permits from the government. Since then, the main activity has been at the Cerro Colorado deposit, which still has important copper and gossan reserves. The Atalaya Riotinto Minera company, a Spanish part of Atalaya Mining, has also helped protect and improve the historical mining and industrial heritage.

Old Industrial Buildings

Since mining started again in the 1700s, many industrial buildings have been constructed. One of the oldest still standing is the San Luis Smelter, built in 1832 next to the South Seam for metal processing. The Rio Tinto Company Limited later built new facilities, such as Fundición Mina (1879), Fundición Huerta Romana (1889), and Fundición Bessemer (1901). They also built Cementación Cerda and Cementación Planes to extract copper using a wet process. Later, all wet metal processes were moved to the Zarandas-Naya area with the building of Cementación Naya and, in 1932, the ferrous sulfate ponds. There was also an acid factory in Riotinto, which started in 1889, followed by a second sulfuric acid plant built in 1929.

As activities grew, RTC provided electricity to its factories, British homes, and worker villages. In 1907, a power plant was built in the Huerta Romana area. It operated from 1909 to 1963.

Starting in the 1880s, ore processing plants were set up in the Zarandas-Naya area. This began a period of industrial growth that peaked in the early 1900s. After this, the area became the main place for processing ore from different deposits and veins. It became the de facto Industrial Hub of Riotinto. In 1907, the new Fundición de Piritas started operations in Zarandas-Naya. This later replaced Fundición Bessemer and stayed in service until 1970. Cementación Naya and, years later, a crushing plant were also built in Zarandas to process pyrites from Corta Atalaya. From the late 1960s, the Riotinto industrial area declined. This was partly because some plants were moved to the new Polo Químico de Huelva and partly because the mines were running out of minerals. The only exception was the building of an industrial plant at Cerro Colorado to extract gold and silver from gossan.

The increase in wet metal processing needed more water. By the late 1800s, water was becoming scarce. By 1878, RTC had already built the Dique Sur near Riotinto town and the Marismilla reservoir south of Nerva. Then, the Campofrío reservoir was built in 1881. The Campofrío reservoir temporarily solved the water shortage and provided drinking water to the towns in the mining basin. In the Peña del Hierro area, upstream of the Tinto river, the company mining there also built two reservoirs for industrial use: Tumbanales I and Tumbanales II. This, along with a severe drought in 1904, made the water supply problem worse. This led RTC to build the Zumajo reservoir between 1907 and 1908. Also, several facilities were set up in the Riotinto basin to store waste materials (tailings) from the ore processing plants. These were the Gossan dam and the Cobre dam, both north of La Dehesa.

Railway Lines

Between 1873 and 1875, RTC engineers built the Riotinto Railway to connect the mines with Huelva. A pier was also built in the Huelva port. Over the years, a large network of tracks and branches was created within the basin. These connected the main line to the industrial buildings and deposits, like Filón Norte and Corta Atalaya. For example, branches were built to connect with the Peña del Hierro mine (1883), and lines reached Zalamea la Real and Nerva (1904). There was also an underground connection through the Naya tunnel (1916). Two railway hubs were also created: Río Tinto-Station and Zarandas-Naya. These had wide tracks for receiving and sorting mining trains. For a long time, the Riotinto railway was one of the most important railway lines in Spain, both for its length and its many trains.

The Peña del Hierro Railway also operated in the basin. It was active between 1914 and 1954. This 21-kilometer-long route connected the Peña del Hierro deposit with the railway line of the Cala Mines. This made it easier to transport the ore to a pier on the Guadalquivir river.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Cuenca minera de Riotinto-Nerva para niños

In Spanish: Cuenca minera de Riotinto-Nerva para niños

- Riotinto Railway

- Rio Tinto Company Limited

- Tourist Mining Train

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |