Roger J. Traynor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

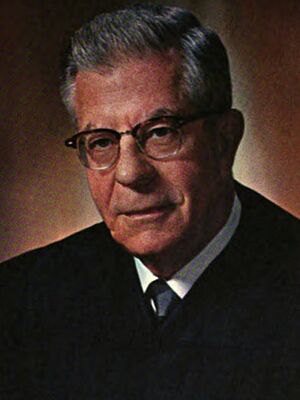

Roger J. Traynor

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 23rd Chief Justice of California | |

| In office September 1, 1964 – February 2, 1970 |

|

| Appointed by | Pat Brown |

| Preceded by | Phil S. Gibson |

| Succeeded by | Donald R. Wright |

| Associate Justice of the California Supreme Court | |

| In office August 13, 1940 – September 1, 1964 |

|

| Appointed by | Culbert Olson |

| Preceded by | Phil S. Gibson |

| Succeeded by | Stanley Mosk |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Roger John Traynor

February 12, 1900 Park City, Utah, U.S. |

| Died | May 14, 1983 (aged 83) Berkeley, California, U.S. |

| Spouse |

Madeline E. Lackman

(m. 1933) |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | University of California, Berkeley (BA, MA, PhD, JD) |

Roger John Traynor (February 12, 1900 – May 14, 1983) was a very important judge in California. He served as the 23rd Chief Justice of California from 1964 to 1970. Before that, he was an associate justice on the Supreme Court of California for many years, from 1940 to 1964. He also worked as a lawyer for the state and taught law at the UC Berkeley School of Law. Many people consider him one of the most creative and influential judges of his time.

Traynor was known for his modern ideas about law. His 30 years as a judge happened during a time of big changes in California and the United States of America. He believed that a bigger role for government in people's lives was a good thing. After he retired from the California Supreme Court, he continued teaching law.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Roger Traynor was born in 1900 in Park City, Utah, which was a mining town back then. His parents, Felix and Elizabeth Traynor, were Irish immigrants who were not wealthy.

In 1919, a high school teacher encouraged him to go to the University of California, Berkeley. He only had $500 to pay for college. But he was a brilliant student and earned a scholarship after his first year because of his excellent grades.

He earned several degrees from UC Berkeley:

- A B.A. in 1923

- A M.A. in 1924

- A Ph.D. in 1926 (all in political science)

- A J.D. (a law degree) from Boalt Hall, UC Berkeley's law school, in 1927

He earned his Ph.D. and J.D. at the same time. He also taught students and was the main editor of the California Law Review. He became a licensed lawyer in California in 1927.

Working in Law and Government

UC Berkeley and State Work

At Boalt Hall, UC Berkeley's law school, Traynor wrote articles about taxation. He became a full-time professor there in 1936. In 1939, he became the Acting Dean of Boalt Hall.

While teaching, Traynor also advised the California State Board of Equalization from 1932 to 1940. He also advised the United States Department of the Treasury from 1937 to 1940. He even took time off from teaching to help these government groups. For example, he helped the Treasury Department write a new tax law in 1938.

Shaping California's Taxes

Before the Great Depression, California mainly funded its government with a property tax. When property values dropped, this system stopped working. Traynor helped create many of California's modern tax laws. These included:

- The vehicle registration fee (1933)

- The sales tax (1933)

- The income tax (1935)

- The use tax (1935)

- The corporate income tax (1937)

- The fuel tax (1937)

He also helped set up the sales tax system across 200,000 retail businesses. In 1940, he started working part-time as a lawyer for California's Attorney General, Earl Warren. Earl Warren later became the Chief Justice of the United States.

Later Teaching Career

After leaving the California Supreme Court in 1970, Traynor became a professor at the UC Hastings College of Law. He also taught at other law schools, including the University of Utah, University of Virginia, and the University of Cambridge.

California Supreme Court

Becoming a Judge

On July 31, 1940, California's Governor Culbert Olson chose Traynor to be a judge on the Supreme Court of California. He was approved on August 13 and started his job that same day. Voters kept him in his position in the election later that year.

In August 1964, the Chief Justice, Phil S. Gibson, retired. Governor Pat Brown then appointed Traynor to be the new Chief Justice.

His Impact on Law

Many people called Traynor one of the greatest judges who never served on the Supreme Court of the United States. He wrote more than 900 legal opinions. He became known as the leading state court judge in the country. During his time, the decisions of the California Supreme Court were often used as examples by other state courts.

Traynor's decisions helped change California from a more traditional state into a modern and innovative one. He was praised for his clear writing and strong legal thinking. He was even made a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, which is a rare honor for a judge. Many of his opinions are still studied by law students today.

Some of his most important contributions include:

- In 1948, he wrote an opinion that struck down a law preventing people of different races from marrying (called miscegenation). California was the first state supreme court to do this.

- In 1952, he wrote an opinion that made it easier for people to get a divorce, helping to pave the way for "no-fault divorce" later on.

- In 1963, he created a new rule called "strict liability" for faulty products. This meant that if a product was unsafe and hurt someone, the company that made it was responsible, even if they didn't mean to cause harm. This was a big step in protecting consumers.

Traynor believed that courts had an important role in solving difficult public problems and holding companies and governments responsible.

Retirement

On January 2, 1970, Traynor announced his retirement. He did this to make sure he would receive his retirement benefits, as a California law would have reduced them if he stayed past age 70. After retiring, he became the chairman of the National News Council, which focused on freedom of the press. He lived in Berkeley until he passed away from cancer in 1983.

Personal Life

On August 23, 1933, Roger Traynor married Madeleine Emilie Lackman. She also loved learning and had a M.A. in political science. She later earned her own law degree (J.D.) in 1956.

They had three sons: Michael, Joseph, and Stephen. Michael followed in his father's footsteps and became a lawyer. He went to Harvard Law School and became a partner at a big law firm. He also served as president of The American Law Institute, a group that works to improve the law.

See also

- US tort law

- US contract law

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of California