Saturnalia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Saturnalia |

|

|---|---|

Saturnalia (1783) by Antoine-François Callet, showing his interpretation of what the Saturnalia might have looked like

|

|

| Observed by | Romans |

| Type | Classical Roman religion |

| Significance | Public festival |

| Celebrations | Feasting, role reversals, gift-giving, gambling |

| Observances | Public sacrifice and banquet for the god Saturn; universal wearing of the pileus |

| Date | 17–23 December |

Saturnalia was an old Roman festival that honored the god Saturn. It started on December 17th in the Julian calendar and later grew to include celebrations until December 23rd. People celebrated with a special offering at the Temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum. After this, there was a big public meal. Then, people gave gifts to each other and had many parties. The festival had a fun, carnival-like feeling where normal Roman rules were turned upside down.

During Saturnalia, people were allowed to gamble. Masters even served food to their slaves. This was because the festival was seen as a time of freedom for everyone, including slaves and those who were once slaves. A popular custom was to choose a "King of the Saturnalia." This king would give funny orders that everyone had to follow. The gifts exchanged were often joke gifts or small statues made of wax or clay, called sigillaria. The poet Catullus once called Saturnalia "the best of days."

Saturnalia was similar to an older Greek holiday called Kronia. This Greek festival was celebrated in midsummer. For some Romans, Saturnalia was very important. They saw it as a return to the ancient Golden Age, a mythical time when Saturn ruled the world. During this time, everyone was happy and free. The philosopher Porphyry thought the freedom of Saturnalia meant that souls could become immortal. Saturnalia might have also influenced some traditions of later winter holidays in Europe, like Christmas and Epiphany. For example, the old European Christmas custom of choosing a "Lord of Misrule" might have come from Saturnalia.

Contents

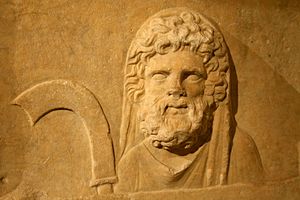

Why Saturnalia Started

In Roman mythology, Saturn was a god of farming. People believed he ruled the world during a "Golden Age." In this time, humans lived without working hard and had everything they needed. The fun and parties of Saturnalia were meant to remind people of this lost, happy time. The Greek festival similar to Saturnalia was the Kronia. It was celebrated in mid-July to mid-August.

Many ancient writers mentioned other similar festivals across the Greco-Roman world. These included festivals where masters ate with their slaves, just like in Saturnalia. One festival, called Hybristica, even had men and women dressing up as each other.

An old Roman historian named Justinus wrote that Saturn was once a real king in Italy. He said:

The first inhabitants of Italy were the Aborigines, whose king, Saturnus, is said to have been a man of such extraordinary justice, that no one was a slave in his reign, or had any private property, but all things were common to all, and undivided, as one estate for the use of every one; in memory of which way of life, it has been ordered that at the Saturnalia slaves should everywhere sit down with their masters at the entertainments, the rank of all being made equal."

—Justinus, Epitome of Pompeius Trogus 43.3

Even though Saturnalia was very famous, no single ancient book describes the whole festival from start to finish. We learn about it from many different writings. A major source is a book by Macrobius, a Latin writer. He described Saturn's rule as "a time of great happiness, both on account of the universal plenty that prevailed and because as yet there was no division into bond and free." This explains why slaves had so much freedom during Saturnalia.

Macrobius also suggested that Saturnalia was a festival of light. It happened around the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year. The many candles used during the festival symbolized the search for knowledge and truth. The return of light and the start of the new year were celebrated later in the Roman Empire on December 25th, called the "Birthday of the Unconquerable Sun."

Saturnalia remained popular even into the 3rd and 4th centuries AD. As the Roman Empire became Christian, many of its customs influenced the celebrations around Christmas and New Year.

Changes Over Time

Saturnalia changed a lot in 217 BC. This was after the Romans lost a big battle to Carthage during the Second Punic War. Before this, they celebrated the holiday in their traditional Roman way. But after checking some special books called the Sibylline Books, they started using "Greek rites." This meant they did sacrifices in the Greek style, had a public feast, and shouted "io Saturnalia!" which became a famous part of the festival.

The Romans often adopted religious practices from other nations. This was especially true during the Second Punic War, when they faced a lot of pressure. Some historians believe the new rites were meant to please Baal Hammon, a Carthaginian god similar to the Roman Saturn. The custom of masters serving their slaves might have even included Carthaginian war captives.

Public Celebrations

Temple Rituals

The statue of Saturn at his main temple usually had its feet tied with wool. For the holiday, these bindings were removed as a sign of freedom. The official ceremonies followed "Greek rite." A priest performed the sacrifice with his head uncovered. Normally, Roman priests covered their heads. This change might have been because Saturn was linked to the Greek god Cronus. It could also have been one of the many "role reversals" of Saturnalia, doing the opposite of what was normal.

After the sacrifice, the Roman Senate held a lectisternium. This was a Greek ritual where a god's statue was placed on a fancy couch, as if the god was there joining the party. Then, a public feast followed.

The day was supposed to be a holiday from all work. Schools closed, and people stopped their exercise routines. Courts were not open, so no legal decisions were made, and no wars could be declared. After the public events, celebrations continued at home. On December 18th and 19th, which were also public holidays, families performed their own rituals. They bathed early, and wealthier families offered a young pig, a traditional gift to an earth god.

Offerings to Saturn

Saturn also had a darker side. One of his partners was Lua, a goddess for whom the weapons of defeated enemies were burned. Saturn was also connected to the underworld and its ruler, Dīs Pater, who was a god of hidden riches. Later Roman writings from the 3rd century AD mention that Saturn received offerings of dead gladiators during or near Saturnalia. These gladiator shows lasted for ten days in December.

Role Reversals and Freedom

Saturnalia was famous for its role reversals and relaxed rules. Slaves were treated to feasts like those their masters usually enjoyed. Ancient writers have different ideas about how this happened. Some say masters and slaves ate together, while others say slaves ate first, or that masters actually served the food. The practice might have changed over time.

During Saturnalia, slaves were even allowed to speak freely to their masters without fear of punishment. The poet Horace called it "December liberty." In some of his poems set during Saturnalia, Horace shows a slave giving sharp criticism to his master. However, everyone knew that this turning of the social order was only for a short time. No social rules were truly broken because the holiday would end.

Roman men usually wore a toga, their traditional clothing. But for Saturnalia, they put on a colorful "dinner outfit" called a synthesis, which was normally considered bad taste for daytime. Roman citizens usually went bare-headed, but during Saturnalia, they wore a pilleus. This was a cone-shaped felt cap, usually worn by freed slaves. Slaves, who normally couldn't wear the pilleus, wore it too. So, everyone wore the cap, showing no difference in status.

Freeborn Roman women also took part in Saturnalia. This is suggested by gifts mentioned for women. Their presence at feasts might have depended on the customs of their time. Later in the Roman Republic, women mixed more freely with men than they had before.

Giving Gifts

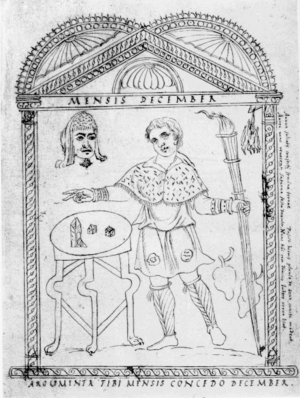

December 19th, called the Sigillaria, was a day for giving gifts. Since valuable gifts would show social status, which went against the spirit of the season, people often gave small clay or wax figures called sigillaria. Candles or "gag gifts" were also common. Emperor Augustus especially loved gag gifts. Children received toys.

The poet Martial wrote many poems about Saturnalia gifts. He mentioned both expensive and very cheap gifts. These included writing tablets, dice, knucklebones, money boxes, combs, toothpicks, hats, hunting knives, axes, lamps, balls, perfumes, pipes, pigs, sausages, parrots, tables, cups, spoons, clothes, statues, masks, books, and even pets. Gifts could be as costly as a slave or an exotic animal. But Martial suggested that small, inexpensive gifts showed the true quality of a friendship. Richer people might give money to their poorer friends or helpers to help them buy gifts. Some emperors were known for celebrating the Sigillaria with great care.

Sometimes, verses or poems came with the gifts, much like modern greeting cards. Martial has a collection of poems written as if they were attached to gifts. Once, Catullus received a book of bad poems as a joke from a friend.

Gift-giving wasn't just on the Sigillaria day. In some homes, guests and family members received gifts after the big feast where slaves had also shared.

When Saturnalia Was Held

Saturnalia was originally held on December 17th. This was the 14th day before the start of January on the oldest Roman religious calendar. This day was a public holiday, meaning no official business could be done. It also marked the day the Temple to Saturn in the Roman Forum was first opened in 497 BC.

When Julius Caesar changed the calendar to match the solar year better, two days were added to December. Saturnalia still fell on December 17th, but this was now the 16th day before January. Because of this change, people felt the original date had moved. So, under Emperor Augustus, Saturnalia was celebrated as a three-day official holiday, covering both dates.

By the end of the Roman Republic, private Saturnalia parties lasted for seven days. But during the time of the Roman Empire, the official holiday was shortened to three to five days. Emperor Caligula made the official celebration five days long.

December 17th was the first day of the astrological sign Capricorn, which was linked to the planet Saturn. The festival's closeness to the winter solstice (December 21st to 23rd) was important. For example, the many wax candles used could symbolize "the returning power of the sun's light after the solstice."

Lasting Influence

Unlike some Roman festivals that were only celebrated in specific places, Saturnalia could be celebrated anywhere in the Roman Empire. It continued as a secular (non-religious) celebration long after it was removed from the official calendar.

Because the dates were so close, many Christians in western Europe kept celebrating old Saturnalia customs along with Christmas and other holidays around that time.

During the late medieval period and early Renaissance, many towns in England chose a "Lord of Misrule" at Christmas. This person would lead the fun during the Feast of Fools. This custom was sometimes linked to Twelfth Night or Epiphany. A common tradition in western Europe was to hide a bean, coin, or other small item in a cake or pudding. Whoever found it would become the "King (or Queen) of the Bean." During the Protestant Reformation, some people tried to stop these practices, calling them "popish" (too Catholic). These efforts were mostly successful. The Puritans banned the "Lord of Misrule" in England, and the custom was soon forgotten. However, the bean in the pudding survived as a tradition in Scandinavia, where a single almond is hidden in Christmas porridge.

Still, in the mid-1800s, some old traditions, like gift-giving, were brought back in English-speaking countries as part of a "Christmas revival." During this time, writers like Charles Dickens wanted to make Christmas a more family-friendly holiday. Some parts of Saturnalia celebrations may still be seen in Christmas traditions today. Giving gifts at Christmas is like the Roman custom of giving sigillaria. Lighting Advent candles is similar to the Roman tradition of lighting torches and wax candles. Also, both Saturnalia and Christmas involve eating, singing, and dancing.

Images for kids

-

Dice players in a wall painting from Pompeii

-

A Roman silver disc showing Sol Invictus (from Pessinus in Phrygia, 3rd century AD)

See also

In Spanish: Saturnales para niños

In Spanish: Saturnales para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |