Siege of Aiguillon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Aiguillon |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Edwardian Phase of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||||

A medieval town under assault. A miniature from a chronicle by Jean Froissart. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 900 *300 men-at-arms *600 archers |

15,000–20,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||||

The siege of Aiguillon was a major event during the Hundred Years' War. It began on April 1, 1346. A large French army, led by John, Duke of Normandy, surrounded the town of Aiguillon in Gascony. The town was defended by an English and Gascon army. This force was commanded by Ralph, Earl of Stafford.

In 1345, Henry, Earl of Lancaster, arrived in Gascony. He brought 2,000 soldiers and a lot of money. In 1346, France decided to focus its efforts on this region. Early in the fighting season, a huge French army of 15,000 to 20,000 men marched down the Garonne River valley. Aiguillon was very important because it controlled both the Garonne and Lot rivers. The French could not advance further into Gascony without capturing it.

Duke John, who was the son of King Philip VI of France, started the siege. The town's defenders, about 900 men, often left the town to attack the French. This made it hard for the French to carry out their plans. Meanwhile, Lancaster kept his main army at La Réole, about 30 miles (48 km) away. This kept the French worried. Duke John could never fully cut off Aiguillon's supplies. His own supply lines were also constantly attacked. Once, Lancaster even brought a large supply train into the town.

In July, the main English army landed in northern France. They began marching towards Paris. King Philip VI repeatedly ordered his son, Duke John, to stop the siege. He wanted Duke John to bring his army north. But Duke John felt it was a matter of honor to capture Aiguillon. He refused to leave. By August, the French army's supplies were running out. Many soldiers were getting sick with dysentery, a serious illness. More and more soldiers were leaving the army. King Philip VI's orders became very strict. On August 20, the French finally gave up the siege. They left their camp and marched away. Six days later, the main French army was badly defeated at the Battle of Crécy. They lost many soldiers. Two weeks after this defeat, Duke John's army joined the remaining French forces.

Contents

Why the War Started

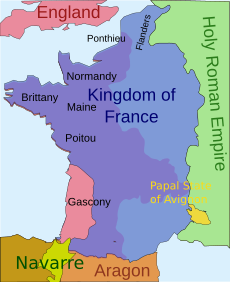

Since the Norman Conquest in 1066, English kings also held lands in France. This meant they were vassals, or loyal subjects, of the French kings. Over time, England's lands in France became smaller. By 1337, only Gascony in southwest France and Ponthieu in northern France remained. The people of Gascony were very independent. They had their own customs and language. They preferred being connected to a distant English king. He usually left them alone. They did not like the idea of a French king who would interfere in their lives.

There were many disagreements between King Philip VI of France and King Edward III of England. On May 24, 1337, Philip's Great Council in Paris decided something important. They said that the Duchy of Aquitaine, which was basically Gascony, should be taken back by France. They claimed Edward had not followed his duties as a vassal. This event started the Hundred Years' War. This long conflict lasted for 116 years.

Gascony's Importance

Before the war, at least 1,000 ships left Gascony every year. They carried over 80,000 tuns of local wine. A tun was a large barrel holding about 252 gallons (954 liters) of wine. The taxes the English king collected on wine from Bordeaux were huge. They were more than all other taxes combined. Bordeaux, the capital of Gascony, had over 50,000 people. This was more than London at the time. Bordeaux was also very rich.

However, by this time, English Gascony had shrunk. It relied on food imports, mostly from England. If shipping stopped, Gascony could starve. England's finances would also suffer greatly. The French knew this very well.

Even though Gascony caused the war, Edward III sent few resources there. When English armies fought in France, they usually went to northern France. Most years, the Gascons had to fight on their own. They were often under great pressure from the French. In 1339, the French even attacked Bordeaux. They broke into the city before being pushed back. Gascons usually had 3,000 to 6,000 soldiers. Most were foot soldiers. But up to two-thirds of them were busy guarding towns.

The border between English and French lands in Gascony was very unclear. Many landowners had scattered properties. They might owe loyalty to different lords for each piece of land. Small estates often had a fortified tower or keep. Larger estates had castles. Fortifications were also built at important crossing points. These helped collect tolls and control military movement. Fortified towns grew near bridges and river crossings.

Armies could find food by searching the area. But they had to keep moving often. If they wanted to stay in one place, like to besiege a castle, they needed water transport for supplies. This included food, animal feed, and siege equipment. Warfare was usually about taking castles and other strong points. It was also about getting the local nobles to switch their loyalty. This region had been changing for centuries. Many local lords served whichever country seemed stronger.

By 1345, after eight years of war, England mostly controlled a strip of coast. This ran from Bordeaux to Bayonne. There were also a few isolated strongholds further inland. In 1345, Henry, Duke of Lancaster, led a very fast campaign. He defeated two large French armies. He captured French towns and forts in much of Périgord and Agenais. This made English Gascony much safer. After this successful campaign, Lancaster's second-in-command, Ralph, Earl of Stafford, marched on Aiguillon. This town was very important. It controlled where the Garonne and Lot rivers met. The people of Aiguillon attacked the French soldiers there. Then they opened the gates to the English.

Preparing for the Siege

John, Duke of Normandy, King Philip VI's son, was put in charge of all French forces in southwest France. He gathered the largest army France had ever sent to this region. It included many royal military officers. Money was always a problem. Duke John even borrowed over 330,000 florins from the Pope. He also had to order local officials to "Amass all of the money you can for the support of our wars. Take it from each and every person you can..." This showed how desperate France's finances were.

A second French army formed at Toulouse. It included a siege train (equipment for attacking castles) and five cannon. Duke John planned to attack and besiege La Réole. This was a large, strong town on the Garonne River. Lancaster had captured it the year before. Aiguillon controlled both the Lot and Garonne rivers. So, taking Aiguillon was essential to supply any army around La Réole.

Lancaster knew that the French could not win if Aiguillon remained English. A historian called it "the key to the Gascon plain." So, he put a very strong group of soldiers there. This included 300 men-at-arms and 600 archers. Stafford commanded them. The town had plenty of supplies. However, its physical defenses were not in good shape. The main wall was new but not finished. Gaps were filled with temporary defenses. A bridge over the Lot River was fortified. It had a barbican gate, but it was very old and not well kept. There were also two small forts inside the town. Both overlooked the Garonne. The Lot River protected the town's northern wall. The Garonne protected the western wall. The southern and eastern walls were easier to attack. Lancaster stayed in La Réole, about 30 miles (48 km) downstream, during the entire siege.

The Siege Begins

Surrounding the Town

The French armies gathered and marched very early in the fighting season. By March, they were in the province of Quercy. The exact size of the French forces is not known. But later in the campaign, they were estimated to be between 15,000 and 20,000 soldiers. Historians have called the French army "huge" and "enormously superior" to the English and Gascon forces. The army marched down the Garonne valley from Agen. They reached Aiguillon on April 1. On April 2, a formal call to arms was announced for all able-bodied men in southern France.

Surrounding the town was a challenge for the French. The two rivers met, creating three different areas. Each area needed to be blocked off. But dividing their army into three parts could lead to defeat. They needed to be able to quickly bring their forces together if one part was attacked. A bridge over the Lot, about 5 miles (8 km) from Aiguillon, was easily taken. But they needed to build a new bridge over the Garonne. Duke John used over 300 carpenters for this. They were protected by 1,400 crossbowmen and many men-at-arms. The town's defenders attacked this work many times. They broke it up twice. But the bridge was finished by the end of May. Each part of the French army built strong earthworks. These protected them from attacks by the defenders and from Lancaster's main army.

Fighting During the Siege

As expected, the large French army quickly used up all the supplies in the surrounding area. So, they relied completely on the rivers for their food and other needs. The English and Gascon army at La Réole attacked French soldiers looking for food. They stopped French supplies. This kept the French in a constant state of worry. Soon, many French soldiers got sick with dysentery.

In mid-June, the French tried to send two large supply barges down the Lot River. They were going to their soldiers west of the Garonne. They had to pass under the fortified bridge held by the defenders. The defenders attacked from the bridge's barbican. They went through the French lines and captured the barges. They brought them into the town. Fierce fighting broke out as the attackers tried to get back to the barbican. After several hours, the French took the barbican. The defenders closed the town gates. Most of the attacking party were trapped outside. The survivors were taken prisoner.

The French could not completely cut off the town. Throughout the siege, the English and Gascons could get small amounts of supplies and reinforcements into Aiguillon. In July, a larger force fought its way through with more supplies. From the start, the French focused their attacks on the southern side of the town. At least twelve large siege engines, probably trebuchets, fired at the town constantly. The results were not good enough. In July, they tried an attack from the north, across the Lot. They used three siege towers on large barges. As they moved across the river, one tower was hit by a missile from an English trebuchet. It overturned, and many soldiers were lost. The attack was stopped.

The siege became very important to Duke John. He had started the siege of Aiguillon. It was a matter of knightly honor not to retreat until the town fell. At one point, he promised not to leave until he had captured the town. By July, the French were getting supplies from over 200 miles (320 km) away. This distance was very hard to manage with 14th-century land transport. In early 1346, the English captured the castle of Bajamont. This was 7 miles (11 km) from Agen, the capital of Agenais. This was one of several strongholds the English used to attack French supply lines. In late July, a French force of 2,000 men marched against it. The small English group, led by Galhart de Durfort, attacked the French. They defeated them and captured their commander. The French army began to starve. Horses died because there was no food for them. The dysentery sickness got worse. More and more soldiers left the army, often joining the English.

French Retreat

In 1345, King Edward III had sent armies to Gascony and Brittany. He had also gathered his main army for fighting in northern France. This army sailed but never landed because a storm scattered the fleet. Knowing Edward III's plans had kept the French focused on the north until late in the fighting season. In 1346, Edward III again gathered a large army. The French knew about this again. The French thought Edward would sail to Gascony. There, Lancaster was greatly outnumbered. To protect against an English landing in northern France, Philip VI relied on his strong navy.

This trust was misplaced. On July 12, an English army of 7,000 to 10,000 soldiers landed in northwest Normandy. This force marched across the richest parts of France. They captured and looted every town in their path. The English fleet sailed alongside them. It destroyed everything up to five miles inland. It also destroyed most of the French navy in its ports. Philip VI ordered his main army, under Duke John, to leave Gascony. After a fierce argument with his advisors, Duke John still refused to move. He said he would not leave until his honor was satisfied.

On July 29, Philip VI called for all able-bodied men in northern France to join the army. On August 7, the English reached the Seine River. Philip VI sent strict orders to Duke John. He insisted that Duke John abandon the siege of Aiguillon and march his army north. Edward III marched southeast. By August 12, his army was 20 miles (32 km) from Paris.

On August 14, Duke John tried to arrange a local truce. Lancaster knew what was happening in the north and in the French camps. He refused the truce. On August 20, after more than five months, the French gave up the siege. They marched away quickly and in disorder. The French camps were left guarded by local soldiers. These soldiers quickly left. All the French army's equipment was captured. This included supplies, materials, siege engines, and many horses. At the start of their retreat, the French soldiers were very disorganized. There are stories of men being pushed off the bridge over the Garonne and drowning. Stafford's soldiers and other local English and Gascon forces chased them closely. Part of Duke John's personal belongings were captured. French castles and small forts along the Lot River upstream from Aiguillon were taken. So were French positions between the Lot and the Dordogne rivers.

What Happened Next

Duke John and his army met King Philip VI around September 7. This was two weeks after the French army in the north, which had 20,000 to 25,000 soldiers, was badly defeated at the Battle of Crécy. They suffered very heavy losses. After Crécy, the French took soldiers from their garrisons in the southwest. They used them to build a new army to face the main English threat in the northeast. The areas facing Lancaster were left almost defenseless.

Lancaster launched three separate attacks between September and November. Local Gascon forces attacked the few major strongholds in the Bazadais region that the French still held. All of them were captured, including the town of Bazas. Other Gascon forces raided to the east, deep into Quercy. They went over 50 miles (80 km) into French territory. A historian named Jonathan Sumption said this "dislocated the royal administration in central and southern France for three months."

Meanwhile, Lancaster himself took a small force. This included 1,000 men-at-arms and possibly 1,000 archers. He went 160 miles (260 km) north on a great mounted raid, called a chevauchée. During this raid, he captured the rich provincial capital of Poitiers. He also took many towns and castles throughout Saintonge and Aunis. With these attacks, Lancaster moved the fighting away from the heart of Gascony. The battles now took place 50 miles (80 km) or more beyond its borders.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |