Lancaster's chevauchée of 1346 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Lancaster's chevauchée of 1346 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Edwardian Phase of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

In autumn 1346, a brave English leader named Henry, Earl of Lancaster, led a series of attacks in southwest France. This was a big part of the Hundred Years' War. These fast attacks were called a chevauchée (say: she-vo-SHAY).

Earlier that year, a huge French army was trying to capture a key town called Aiguillon. This town was in Gascony, an area controlled by England. Lancaster's forces kept the French from getting supplies. After five months, the French army had to leave. They were called north to fight the main English army. That army had landed in Normandy in July, led by King Edward III of England.

When the French army left, their defenses in southwest France became very weak. Lancaster quickly took advantage of this. He launched attacks into different areas. He also led a large raid himself. This raid involved about 2,000 English and Gascon soldiers. They rode 160 miles (260 km) north and captured the rich city of Poitiers. His soldiers then burned and looted many areas. They also captured many towns and castles. These attacks completely messed up the French defenses. The fighting moved far away from the heart of Gascony.

Contents

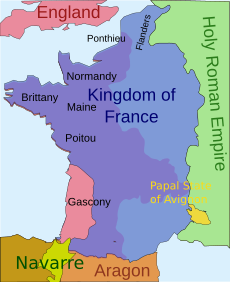

Why the War Started

Since 1066, English kings had owned lands in France. This made them vassals, or loyal subjects, of the French kings. By 1337, England only held Gascony in southwest France and Ponthieu in northern France. The people of Gascony liked having a distant English king. He let them manage their own affairs. The French king, however, wanted to control them more.

King Philip VI of France and King Edward III of England had many disagreements. On May 24, 1337, Philip's council decided to take Gascony back. They said Edward had not followed his duties as a vassal. This decision started the Hundred Years' War. This war lasted for 116 years.

Before the war, many ships left Gascony each year. They carried over 80,000 tuns of wine. A tun was a large barrel holding 252 gallons (954 liters) of wine. The taxes on wine from Bordeaux were the biggest source of money for the English king. Bordeaux, the capital of Gascony, was a very rich city. It had over 50,000 people, more than London. However, English Gascony had shrunk. It had to import food, mostly from England. If ships stopped coming, Gascony would starve. England would also lose a lot of money. The French knew this well.

The border between English and French lands in Gascony was confusing. Many landowners had scattered properties. They might owe loyalty to different lords for each one. Small estates often had a fortified tower. Larger ones had castles. Fortified towns grew around bridges and river crossings. These towns collected tolls and controlled military movement. Armies could find food by moving often. But to stay in one place, like to attack a castle, they needed supplies by water.

Gascony was the main reason for the war. But often, the Gascons had to fight alone. They were usually under pressure from the French. In 1339, the French even attacked Bordeaux. They broke into the city before being pushed back. Gascons usually had 3,000 to 6,000 soldiers. Most were foot soldiers. But up to two-thirds were busy guarding places. The war was often about taking castles and getting local nobles to switch sides.

The 1345 Campaign

By 1345, England only controlled a narrow strip of land. It went from Bordeaux to Bayonne. There were also a few strongholds inland. In 1345, King Edward III sent Henry, Earl of Lancaster to Gascony. Edward planned to send his main army to northern France. But a storm scattered his fleet, so they never landed.

The French focused on the north because of Edward's plans. Meanwhile, Lancaster led a very fast campaign in Gascony. He defeated two large French armies. He captured French towns and forts. This gave England more control in Gascony. After this success, Lancaster's second-in-command, Ralph, Earl of Stafford, marched on Aiguillon. This town was very important. It controlled where the Garonne and Lot rivers met. The people of Aiguillon attacked the French soldiers there. Then they opened the gates to the English.

French Attacks in 1346

John, Duke of Normandy, King Philip VI's son, was in charge of all French forces in southwest France. In March 1346, a French army of 15,000 to 20,000 soldiers marched on Aiguillon. This army was much bigger than any English or Gascon force. They began to besiege Aiguillon on April 1. On April 2, a special order was given for all men in southern France to join the army. This was called an arrière-ban. France put all its money and effort into this attack.

King Edward III again gathered a large army in England. The French knew about this. But they thought Edward would sail to Brittany or Gascony. They believed he would try to help Aiguillon. To stop any English landing in northern France, Philip VI relied on his strong navy. But this was a mistake. On July 12, Edward III successfully crossed the Channel. He landed in northern Normandy with 12,000 to 15,000 soldiers.

The English completely surprised the French. They marched south, destroying towns and burning lands. Philip VI immediately ordered his main army, under Duke John, to leave Gascony. Duke John argued with his advisors. He refused to move until his honor was satisfied. On July 29, Philip VI called for another arrière-ban in northern France. On August 7, the English reached the Seine River. Philip VI again ordered Duke John to leave Aiguillon and march north.

Edward III marched southeast. By August 12, his army was 20 miles (32 km) from Paris. On August 14, Duke John tried to make a local peace agreement. But Lancaster knew what was happening in the north. He refused. On August 20, after more than five months, the French gave up the siege. They marched away quickly and in disorder. Duke John did not rejoin the French army in the north until after they had lost badly at the Battle of Crécy six days later.

English and Gascon Attacks

When Duke John's army left, the French lost control in southern Périgord and most of Agenais. The French only held strongholds in the Garonne valley. These included Port-Sainte-Marie, Agen, and Marmande. The English took control of the whole Lot valley below Villeneuve. They also took most of the remaining French outposts between the Lot and the Dordogne rivers. Lancaster captured most towns without a fight.

John, Count of Armagnac, became the French royal leader in the region. But he struggled to fight back. He had too few soldiers and not enough money. King Philip VI also kept changing his orders. Count John offered to resign within three months.

Lancaster now had the upper hand. In early September, he launched three separate attacks.

- English supporters in Agenais, led by Gaillard I de Durfort, blocked Agen and Porte Sainte Marie. They also raided into Quercy.

- A large group of Gascons, led by Alixandre de Caumont, took back French-held land south and west of the Garonne.

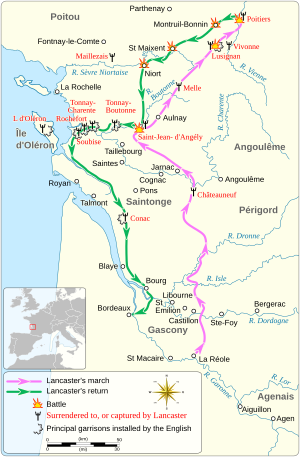

- Lancaster himself led 1,000 knights and 1,000 mounted foot soldiers north on September 12. Most of these were Gascons.

The force in Agenais raided deep into Quercy, over 50 miles (80 km). Gaillard, with 400 cavalry, captured the small town of Tulle. This caused great panic in the province of Auvergne. Count John's army had to go to Tulle. They besieged it from mid-November until late December. The Gascon soldiers there surrendered and were taken prisoner. This small force tied down the entire French army of the southwest. A historian named Jonathan Sumption said this "disrupted the royal government in central and southern France for three months."

The troops under Caumont swept through the Bazadais region. They captured many French towns and forts easily. Many towns surrendered after talks. For example, Bazas gave up after getting good terms for trade through English lands. The French presence in the area almost disappeared.

Lancaster's Great Raid

Lancaster aimed for the rich city of Poitiers. This city was deep in French land, 160 miles (260 km) north of where he started. He rode from the Garonne River to the Charente River, 80 miles (130 km), in eight days. He captured Châteauneuf-sur-Charente. Then he rode 40 miles (64 km) to Saint-Jean-d'Angély to free some English prisoners. Saint-Jean-d'Angély was attacked, captured, and looted.

Lancaster left soldiers there and rode back towards Poitiers. He covered 20 miles (32 km) a day. He took the towns of Melle and Lusignan along the way. Lancaster reached Poitiers late on October 3.

Poitiers was in a strong natural position. But its defenses had not been kept up for centuries. The city had no royal soldiers. The townspeople and local nobles had stopped guarding it. Different church groups and the town shared defense duties. This meant no one took effective action. The English attacked right away. But they were pushed back by a group of local nobles. During the night, the English found a hole in the wall. It had been made years ago for easy access to a watermill. In the morning, they took the hole and forced their way into eastern Poitiers. They killed everyone they saw. Only those who looked rich enough to pay a ransom were spared. Most people fled the city. But over 600 were killed. The town was thoroughly looted for eight days.

Lancaster could not take the royal mint at Montreuil-Bonnin, 5 miles (8 km) west of Poitiers. He quickly marched back to Saint-Jean-d'Angély. He did not try to hold Poitiers. In the province of Poitou, he only left soldiers at Lusignan. This was a small town with good walls and a strong castle. Once back in Saintonge, he took control of the Boutonne valley all the way to the sea. This included the big port of Rochefort and the strong island of Oléron. Lancaster then marched south. He took many small towns and forts.

The French still controlled much of Saintonge. They held the eastern parts and bigger forts. These included the capital, Saintes, and its strongest castle, Taillebourg. They also held important strongholds on the east bank of the Gironde River. Lancaster arrived in Bordeaux, the capital of English Gascony, on October 31. This was seven weeks after he started his great raid. He returned to England in early 1347.

What Happened Next

Lancaster left soldiers in the captured towns and castles. These were in Saintonge and Aunis. A very large group of soldiers stayed at Saint-Jean-d'Angély. The English and Gascons got supplies by raiding French lands. A historian said they were "not so much expected to control territory as to create chaos and insecurity."

Whole provinces, which the French had held securely, were now full of bandits and soldiers from both sides. People moved from villages to safer towns. Townspeople who could, left the area. Much farmland was not used. The French could not fight back well. They focused on defending new weak spots. They also tried to get back towns captured deep in what had been safe areas, like Tulle. French trade went down. Their tax money from the area was greatly reduced. Lancaster had moved the fighting far away from Gascony.

The English army in the north, after winning at Crécy, went on to besiege Calais. Lancaster joined them there in summer 1347. He was there when Calais fell after an eleven-month siege. This gave England a key port in northern France. It was held for two hundred years. The war in southwest France stayed far from Gascony.

In 1355, King Edward III's oldest son, Edward, the Black Prince, led a huge chevauchée north from Bordeaux. It caused much destruction in France. After another big raid in 1356, the French army, led by Duke John (now King John II of France), stopped the English. The English were outnumbered. They were forced to fight 3 miles (5 km) from Poitiers. The French were soundly defeated, and King John was captured.

Images for kids

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |