Siege of Namur (1695) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Namur (1695) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Nine Years' War | |||||||

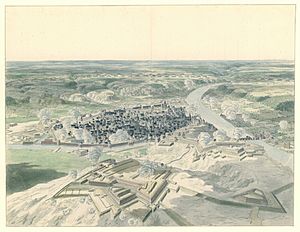

Siege of Namur (1695) by Jan van Huchtenburg. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Grand Alliance |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 13,000-16,000 | 58,000-80,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 8,000 | 18,000 | ||||||

The 1695 Siege of Namur was a major battle during the Nine Years' War. It happened between July 2 and September 4, 1695. The city of Namur was first captured by the French in 1692. Then, the Grand Alliance took it back in 1695. These two events are often seen as key moments of the war. The second siege is known as William III's biggest military success in the conflict.

Contents

Why Namur Was Important

Namur was a city split into two main parts. There was the 'City' where people lived and worked. Then there was the Citadel, a strong fortress. The Citadel controlled access to the Sambre and Meuse rivers. In 1692, a Dutch engineer named Menno van Coehoorn made the Citadel very strong. However, the soldiers defending it were not well-trained.

When the French attacked in 1692, the outer City fell quickly. But taking the Citadel was much harder. It took the French over a month. They almost gave up because of heavy rain and sickness. After the French captured Namur, they made its defenses even stronger. This was done by a famous French engineer named Vauban.

The War So Far

After 1693, the French king, Louis XIV, mostly played defense. French victories like taking Namur, Mons, Huy, and Charleroi did not make the Dutch Republic quit the war. The war was very expensive for France. Bad harvests in 1693 and 1694 caused many people to go hungry.

The Dutch Republic stayed strong. The Grand Alliance, led by William, remained united. They had suffered losses, but they were not defeated. By 1694, they had taken back towns like Huy and Diksmuide. For the first time, the Alliance had more soldiers than the French.

However, the Allies were also running low on resources. The 1690s were a very cold and wet time in Europe. This period is called the "Little Ice Age." It caused food shortages, especially in Spain and Scotland. Many people died from hunger during these years.

Importance of Flanders

The fighting often happened in a region called Flanders. Most of the battles took place in the Spanish Netherlands. This area was flat and had many canals and rivers. In the 1600s, goods and supplies were moved mostly by water. So, controlling rivers like the Lys, Sambre, and Meuse was very important.

Taking back Namur became the main goal for the Allies in 1695. Its location between the Sambre and Meuse rivers made it a key part of the "Barrier" system. This was a line of fortresses in the Spanish Netherlands. The Dutch believed these forts were vital to protect against French invasions. Owning Namur would also give them a strong position in any peace talks.

New Commanders and Plans

The French commander in Flanders, Marshal Luxembourg, died in January 1695. He was replaced by the less skilled Villeroi. The French plan for 1695 was to stay on defense. Boufflers spent time building defenses between the Scheldt and Lys rivers.

In June, William marched towards these defenses with most of the Allied army. But secretly, he sent Frederick of Prussia to Namur. Once Frederick was in place on July 2, William joined him. The Allies now had two groups: a force of 58,000 soldiers besieging Namur. The other group was a field army of 102,000 soldiers under Prince Vaudémont. This army was there to keep Villeroi away from Namur.

The Siege of Namur

On July 2, the Earl of Athlone surprised the French by surrounding Namur with his cavalry. Even though it was a surprise, Boufflers had between 13,000 and 16,000 soldiers. This made the siege a very difficult challenge. Soon after Athlone's move, the Allies built a line of defenses around the city. This was to stop anyone from getting in or out.

When the heavy guns arrived on July 12, the Brandenburg soldiers started firing at the City. The next day, the Dutch began firing near the St. Nicolas Gate. There was heavy fighting, and both sides lost many soldiers. On July 18, the French attacked the Brandenburg position. But the Dutch, led by Major General Ernst Wilhelm von Salisch, captured three small forts outside the St. Nicholas Gate. They pushed the French back into the city.

On June 27, William III himself led a successful attack. About 400 Dutch and English soldiers attacked a key outer defense. At the same time, Maximilian of Bavaria took over an abbey. From there, he forced over 300 French dragoons into the Citadel. After more Allied successes, the French decided to give up the City. By August 4, only the Citadel was still held by the French. Half of the French soldiers had been lost. Count Guiscard, the Governor of Namur, asked for a break in fighting. This allowed the French to move into the Citadel. The siege then continued after six days. However, the Allies needed more money to pay workers before they could attack the Citadel.

Vaudémont's job was to keep his army between Villeroi and Namur. Villeroi tried to trick Vaudémont into moving away. He attacked Allied towns like Knokke and Beselare. But Vaudémont did not fall for the trick. Both sides knew that the longer the siege lasted, the more likely Namur was to fall. Villeroi's attempts to outsmart Vaudémont failed. He did capture Diksmuide and Deinze in late July, taking 6,000 to 7,000 prisoners.

The French also bombed Brussels from August 13 to 15. This destroyed much of the city's business center. But it also failed to make the Allies move away from Namur. Constantijn Huygens, William's secretary, visited Brussels later. He wrote that the damage was "horrible" and many houses were "reduced to rubble."

By mid-August, the Citadel was still mostly intact. Villeroi was making it harder for the Allies to get supplies. The besieging army was also losing soldiers to sickness. In those days, more soldiers died from illness than in battle. The Allies were running out of time. Coehoorn and William decided on a new plan. They set up 200 guns in Namur City. On August 21, they began firing non-stop for 24 hours at the Citadel's lower defenses. Boufflers later told King Louis that it was "the most amazing artillery ever seen." By August 26, the Allies were ready to attack the Citadel.

At midnight on August 27, Villeroi finally reached Vaudémont's army. Villeroi had more soldiers, 120,000 to 102,000. But the Allied positions were very strong. Villeroi could not get around the Allied lines, so he retreated. William then ordered a full attack on the Citadel.

The Allied attacks were very bloody. One attack on August 30 cost 3,000 men in less than three hours. But the defenders were slowly pushed back to their last defenses. Count Guiscard, who was in charge of Fort Orange, told Boufflers on September 2 that they could not stop another attack. The French soldiers gave up on September 4. They had lost 8,000 men, while the Allies lost 18,000.

What Happened Next

Taking back Namur was a big success for the Allies. But Boufflers' strong defense stopped them from taking advantage of French weakness elsewhere. King Louis recognized Boufflers' efforts by making him a Field-Marshall. Neither side could launch a major attack in 1696. Serious fighting mostly stopped. King Louis made one last show of force before the Treaty of Ryswick was signed in September 1697.

Namur showed how effective Coehoorn's attack methods were. It also showed his ideas for defense. He believed that just relying on strong walls was not enough. He also thought that trying to hold an entire town meant risking losing it quickly. His idea was to divide defenses into inner (Citadel) and outer (City) parts. He also believed in an "active" defense. This meant constantly launching small attacks to keep the attackers off guard. Boufflers used these ideas. But he put too many soldiers in the outer City without a way to retreat.

He would use these lessons later at the Siege of Lille in 1708. Historian John Lynn said that Boufflers showed that "one could effectively win a campaign by losing a fortress." This meant if you could tie down and wear out the attacking army in the process. He used a classic active defense. He launched attacks from his soldiers on the enemy's siege works. He fought hard against every advance.

Normally, prisoners were exchanged quickly. This was because neither side wanted to pay to feed them. But this time, the French refused to return the 6,000 to 7,000 Allied soldiers captured at Diksmuide and Deinze. This was due to a disagreement about how they had surrendered. By this time, all armies had a shortage of soldiers. Many captured soldiers were forced to join French regiments. They were sent to fight in Italy or Spain. It was common for soldiers to desert one army to join another. They would get a bonus for signing up. This was especially true because these bonuses were paid right away. Regular wages were often months late. Since recruiters were paid for each new soldier, this meant big profits for French officers. In return, even though the Namur soldiers were allowed to surrender, Boufflers was taken prisoner. He was only released when the Allied prisoners were returned in September.

Legacy and Impact

The bombing of Brussels did not distract the Allies. But some people see it as the end of an era. It showed that fortified towns could no longer resist the huge firepower of modern warfare. This led to a shift away from siege warfare. Instead, armies started to prefer direct battles. This was the approach favored by leaders like Marlborough.

The two sieges of Namur created a lot of public interest. There are few other times in early modern history when the media talked so much about military events. In the Dutch Republic, France, and England, many praises, pictures, maps, and medals were made about the sieges. Newspapers wrote about the events in great detail. Much of this was done by publishers on their own. But governments also encouraged it. They hoped to keep the public interested and supportive of the war. They also wanted to make their allies more confident and lower the enemy's morale. Both William and Louis also saw this publicity as a chance to improve their own reputations.

The attack by 3,000 British soldiers on August 31 is said to have inspired the song "The British Grenadiers".

The siege is also a central part of the novel Mother Ross; an Irish Amazon. This book is an updated version of a story by Daniel Defoe. It claims to be about Christian "Kit" Cavanagh, an Irish woman. She joined the British Army in 1693 disguised as a man. She was present at the siege. Defoe claimed to have met her when she was old. The book has some mistakes, but it gives a rare look at the siege from a common soldier's point of view.

Laurence Sterne's 1760 novel Tristram Shandy mentions events from the Nine Years' War. This includes Namur, where Tristram's uncle Toby got an injury. Uncle Toby and his servant Corporal Trim build a model of the battle in his garden. He shows it to his fiancée, Widow Wadman. The Widow tries to find out how serious Toby's injury is before marrying him. But he avoids her questions by giving more and more detailed stories about the siege. This part of the story appears in the 2006 film A Cock and Bull Story.

Fourteen British regiments received a special honor called "Namur 1695." This included famous regiments like the Grenadier, Coldstream, and Scots Guards.

Images for kids

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |