Sino-Burmese War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sino-Burmese War (1765–1769) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Ten Great Campaigns | |||||||

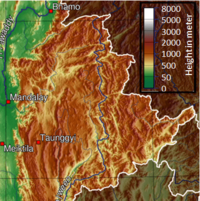

Burma and China prior to the war (1765) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Co-belligerents: |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Qianlong Emperor Liu Zao † Yang Yingju Ming Rui † E'erdeng'e Aligui † Fuheng (DOW) Arigun † Agui |

|||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

Mongols Tai-Shan militias |

|||||||

| Bamar and Shan levies | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

First invasion:

Second invasion:

Third invasion:

Fourth invasion:

|

First invasion Total:2500

Second invasion:

Third invasion: Fourth invasion: |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2nd campaign: ~20,000 |

Burmese Royal horse army (3,000), Shan local army (500-2,000), Burmese army (10,000) | ||||||

The Sino-Burmese War was a series of battles between the Qing dynasty of China and the Konbaung dynasty of Burma (now Myanmar). China's Qianlong Emperor launched four invasions of Burma between 1765 and 1769. These invasions were part of his famous Ten Great Campaigns, which were big military actions he ordered.

However, the war was very difficult for China. Over 70,000 Chinese soldiers and four commanders died. Some people call it "the most disastrous border war" China ever fought. Burma's strong defense helped it stay independent. This war also helped create the border we see today between the two countries.

At first, the Chinese emperor thought the war would be easy. He sent only soldiers from the Green Standard Army who were based in Yunnan. Most Burmese soldiers were busy fighting in Siam at the time. But the experienced Burmese troops still defeated the first two Chinese invasions in 1765–1766 and 1766–1767 at the border.

The fighting then grew into a major war. The third invasion (1767–1768) was led by elite Manchu Bannermen, who were special Chinese soldiers. They almost won, getting very close to the Burmese capital, Ava. But these soldiers from northern China struggled in the hot, wet jungle and got sick. They were forced to retreat with many losses.

After this close call, King Hsinbyushin of Burma brought his armies back from Siam to fight the Chinese. The fourth and largest invasion got stuck at the border. The Chinese forces were completely surrounded. In December 1769, the commanders from both sides agreed to a truce.

China kept many soldiers near the border for about ten years, hoping to fight again. They also stopped trade between the two countries for twenty years. Burma also worried about China and kept soldiers along the border. In 1790, Burma and China started talking again. China saw this as Burma giving up and claimed victory. But the real winners of this war were the Siamese. They got back most of their land after losing their capital, Ayutthaya, to Burma in 1767.

Contents

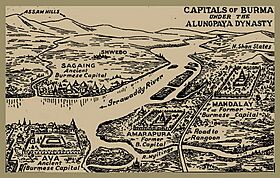

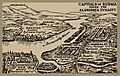

Why the War Started

The border between Burma and China was not clearly marked for a long time. In the 1300s, China's Ming dynasty took control of some border areas. Later, in 1557, King Bayinnaung of Burma's Toungoo dynasty conquered the Shan States. These states are now parts of Kachin State, Shan State, and Kayah State.

The border was never officially drawn. Local Shan chiefs, called sawbwas, often paid taxes to both China and Burma. In the 1730s, China's Qing dynasty started to control its border areas more tightly. At the same time, Burma's Toungoo dynasty was getting weaker.

China Takes More Control (1730s)

When China tried to control the border more, local chiefs fought back. In 1732, the Chinese government in Yunnan asked for higher taxes. This led to several revolts by the Shan people. Shan leaders told their people, "Our land and water are ours. We grow our own food. We don't need to pay taxes to a foreign government."

A Shan army surrounded a Chinese army base in Pu'er for 90 days. China sent about 5,000 soldiers to stop the siege. They chased the Shan rebels but couldn't completely defeat them. So, China changed its plan. They made deals with some Shan sawbwas who were not fighting. China gave them special titles and powers. By the mid-1730s, many sawbwas who used to pay taxes to both sides started siding with the stronger Chinese.

By 1735, when the Qianlong Emperor became the ruler of China, ten sawbwas had joined China. These areas included Mogaung and Bhamo in today's Kachin State, and Hsenwi State (Theinni) and Kengtung State (Kyaingtong) in today's Shan State.

While China was taking more control, Burma's Toungoo dynasty was facing many problems. They had attacks from outside and rebellions inside. In 1740, the Mon people in southern Burma revolted and created their own kingdom. By 1752, the Toungoo dynasty was overthrown.

Burma Fights Back (1750s–1760s)

In 1752, a new Burmese dynasty called Konbaung began to rise. They fought against the Mon kingdom and brought much of Burma back together by 1758. From 1758 to 1759, King Alaungpaya, who started the Konbaung dynasty, sent his army to the faraway Shan States. These were the areas China had taken over twenty years before. Alaungpaya wanted to bring them back under Burmese rule.

Some of the Shan sawbwas and their soldiers ran away into Yunnan, China. They tried to convince Chinese officials to invade Burma. The Chinese government in Yunnan told the Emperor about this in 1759. The Emperor ordered his army to take back the land.

At first, Chinese officials tried to use local militias to solve the problem. But this didn't work. In 1764, a Burmese army was on its way to Siam and was taking more control of the border areas. The sawbwas complained to China again. The Emperor then sent Liu Zao, an important official, to fix things. Liu Zao realized that local militias were not enough. He decided to use regular Chinese soldiers.

First Invasion (1765–1766)

In early 1765, a Burmese army of 20,000 soldiers, led by General Ne Myo Thihapate, left Kengtung to invade Siam. With the main Burmese army gone, Liu Zao used small trade arguments as an excuse to invade Kengtung in December 1765.

The Chinese invasion force had 3,500 Green Standard Army soldiers and local Shan militias. They tried to capture Kengtung. But they couldn't defeat the experienced Burmese soldiers at the Kengtung fort, led by General Ne Myo Sithu. The Burmese broke the siege and chased the invaders into China's Pu'er Prefecture, where they defeated them. Ne Myo Sithu left more soldiers at Kengtung and went back to Ava in April 1766.

Governor Liu was embarrassed and tried to hide what happened. When the Emperor suspected something, he ordered Liu to return and be demoted. Instead, Liu took his own life. This made the Emperor very angry. Defeating Burma became a matter of pride for the Emperor. He then appointed Yang Yingju, an experienced officer, to lead the next invasion.

Second Invasion (1766–1767)

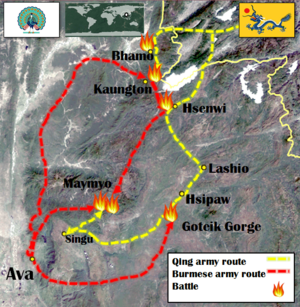

Yang Yingju arrived in the summer of 1766. Unlike the first invasion, which was far from Burma's main areas, Yang wanted to attack Upper Burma directly. He planned to put a Chinese ruler on the Burmese throne. Yang's plan was to go through Bhamo and down the Irrawaddy River to Ava.

The Burmese knew the invasion route. King Hsinbyushin planned to let the Chinese enter Burmese land and then surround them. The Burmese commander, Balamindin, was told to leave Bhamo and stay at the Burmese fort at Kaungton, a few miles south of Bhamo. The Kaungton fort had cannons operated by French gunners. Another Burmese army, led by Maha Thiha Thura, was ordered to march to Bhamo from the east.

The Trap at Bhamo–Kaungton

As planned, the Chinese soldiers easily captured Bhamo in December 1766 and set up a supply base. They then tried to capture the Burmese fort at Kaungton. But Balamindin's defenses were strong, and they stopped many Chinese attacks. Meanwhile, two other Burmese armies, led by Maha Sithu and Ne Myo Sithu, surrounded the Chinese. Maha Thiha Thura's army also arrived near Bhamo, blocking the Chinese escape route back to Yunnan.

The Chinese soldiers were not ready for the hot, tropical weather of Upper Burma. Thousands of them got sick with diseases like cholera and malaria. One Chinese report said that 800 out of 1,000 soldiers in one base died from sickness, and another 100 were ill.

With the Chinese army weakened, the Burmese attacked. First, Ne Myo Sithu easily took back Bhamo. The main Chinese army was now completely trapped in the Kaungton-Bhamo area, with no supplies. The Burmese then attacked the main Chinese army from two sides: Balamindin's army from Kaungton and Ne Myo Sithu's army from the north. The Chinese tried to retreat but were met by Maha Thiha Thura's army. The Chinese army was completely destroyed. Maha Sithu's army also defeated other Chinese bases at the border. The Burmese armies then took control of eight Chinese Shan states in Yunnan.

After the Battle

The victorious Burmese armies returned to Ava with captured weapons and prisoners in early May. In Kunming, China, Yang Yingju lied to the Emperor. He reported that Bhamo was captured, that its people were wearing Chinese hairstyles, and that the Burmese commander, Ne Myo Sithu, had asked for peace after losing many men. He suggested the Emperor accept peace to restart trade.

However, the Qianlong Emperor knew the report was false. He ordered Yang back to Beijing. When Yang arrived, he took his own life on the Emperor's orders.

Third Invasion (1767–1768)

China Prepares for War

After two defeats, the Chinese Emperor and his court couldn't understand how a smaller country like Burma could stand against the mighty Qing. The Emperor felt it was time for the Manchus themselves to fight. He had always doubted his Chinese Green Standard Army soldiers. The Manchus saw themselves as strong warriors.

In 1767, the Emperor appointed Ming Rui, his son-in-law and a skilled Manchu commander, to lead the Burma campaign. Ming Rui had fought against other groups in the northwest. His appointment showed that this was no longer a small border fight but a full-scale war. Mongol and elite Manchu soldiers were sent from northern China. Thousands of Green Standard soldiers from Yunnan and Shan militias also joined. Provinces across China sent supplies. The total Chinese force was 50,000 men, mostly foot soldiers. The mountains and thick jungles of Burma made it hard to use many horse soldiers. China also tried to plan the campaign for winter, hoping fewer soldiers would get sick.

Burma Prepares for War

Burma now faced the largest Chinese army ever sent against them. But King Hsinbyushin didn't seem to fully understand how serious the situation was. During the first two invasions, he had refused to call back his main armies, which were fighting in Laos and Siam. They had been besieging the Siamese capital of Ayutthaya since January 1766. Even after Ayutthaya was captured in April 1767, Hsinbyushin kept some troops in Siam. He even let many Shan and Laotian soldiers go home.

So, when the third invasion began in November 1767, Burma's defenses were not ready for such a large and determined enemy. The Burmese commanders were mostly the same as in the second invasion. Maha Sithu led the main Burmese army and was in charge of the Chinese front. Maha Thiha Thura and Ne Myo Sithu commanded two other armies. Balamindin again defended the Kaungton fort. The main Burmese army was only about 7,000 strong. The total Burmese defense at the start was probably no more than 20,000 soldiers.

China's Attack

Ming Rui planned a two-part invasion. His main Chinese army would go towards Ava through Hsenwi, Lashio, and Hsipaw. The second army, led by General E'erdeng'e, would try the Bhamo route again. The goal was for both armies to meet and attack the Burmese capital, Ava. The Burmese planned to hold off the second Chinese army at Kaungton and meet Ming Rui's main army in the northeast.

At first, China's plan worked well. The smaller Chinese army attacked and took Bhamo. Within eight days, Ming Rui's main army captured the Shan states of Hsenwi and Hsipaw. Ming Rui made Hsenwi a supply base and left 5,000 soldiers there to protect it. He then led 15,000 soldiers towards Ava. In late December, at the Battle of Goteik Gorge, the two main armies fought. Maha Sithu's Burmese army was much smaller and was defeated by Ming Rui's special Bannermen. Maha Thiha Thura was also pushed back. News of this defeat reached Ava. King Hsinbyushin finally understood how serious the situation was and urgently called back Burmese armies from Siam.

After defeating the main Burmese army, Ming Rui pushed forward quickly, taking town after town. He reached Singu on the Irrawaddy River, 30 miles north of Ava, in early 1768. The only good news for the Burmese was that the northern Chinese army, which was supposed to join Ming Rui, had been stopped at Kaungton.

Burma Fights Back

In Ava, King Hsinbyushin stayed calm, even with a large Chinese army of about 30,000 soldiers close by. His court urged him to run away, but he refused. He said he and his brothers would fight the Chinese themselves if needed. Instead of defending the capital directly, Hsinbyushin calmly sent an army to positions outside Singu, leading his men towards the front lines.

It turned out that Ming Rui had gone too far. He was too far from his main supply base in Hsenwi, hundreds of miles away in the northern Shan Hills. Burmese guerrilla attacks on his long supply lines through the jungle were making it hard for the Chinese army to move forward. General Teingya Minkhaung led these Burmese attacks. Ming Rui now tried to defend his position, waiting for the northern army to help him. But that army never came. The northern army had lost many soldiers trying to attack the Kaungton fort. Its commander, E'erdeng'e, went back to Yunnan against Ming Rui's orders. The Emperor later had him executed.

Things got worse for Ming Rui. By early 1768, experienced Burmese soldiers from Siam began to arrive. With these new soldiers, two Burmese armies led by Maha Thiha Thura and Ne Myo Sithu successfully took back Hsenwi. The Chinese commander there took his own life. The main Chinese army was now cut off from all supplies. It was March 1768. Thousands of Chinese soldiers, who were used to cold climates, began dying from malaria and Burmese attacks in the hot weather of central Burma. Ming Rui gave up hope of reaching Ava. He tried to get back to Yunnan with as many soldiers as possible.

Battle of Maymyo

In March 1768, Ming Rui began his retreat. A Burmese army of 10,000 foot soldiers and 2,000 horse soldiers chased him. The Burmese then split their army to surround the Chinese. Maha Thiha Thura was now in charge. The smaller Burmese army, led by Maha Sithu, kept chasing Ming Rui. The larger army, led by Maha Thiha Thura, went through the mountains to get behind the Chinese.

The Burmese successfully surrounded the Chinese at modern-day Pyin Oo Lwin (Maymyo), about 50 miles northeast of Ava. For three days of fierce fighting at the Battle of Maymyo, the Chinese Bannerman army was completely destroyed. The fighting was so intense that the Burmese soldiers' sword handles were slippery with enemy blood. Out of the original 30,000 Chinese soldiers, only 2,500 survived and were captured. The rest were killed in battle, died from disease, or were executed after surrendering. Ming Rui himself was badly wounded. A small group managed to escape. Ming Rui could have escaped with them, but he cut off his pigtail and sent it to the Emperor as a sign of his loyalty. Then, he took his own life. In the end, only a few dozen soldiers from the main Chinese army made it back.

Fourth Invasion (1769)

Break in Fighting (1768–1769)

The Qianlong Emperor had sent Ming Rui and his special Bannermen expecting an easy win. He had even started planning how he would rule his new territory. For weeks, the Chinese court heard nothing. Then, the terrible news finally arrived. The Emperor was shocked. He ordered all military actions to stop until he could decide what to do next. Generals returning from the front warned that Burma could not be conquered. But the Emperor felt he had no choice but to continue. His imperial pride was on the line.

The Emperor turned to Fuheng, one of his most trusted advisors and Ming Rui's uncle. Fuheng had supported the Emperor's decision to fight the Dzungars years earlier. On April 14, 1768, the court announced Ming Rui's death and appointed Fuheng as the new chief commander for the Burma campaign. Other important Manchu generals, Agui, Aligun, and Suhede, were made his deputies. The top military leaders of China were now ready for a final battle with Burma.

Before fighting started again, some Chinese tried to make peace with Burma. The Burmese also showed they wanted peace because they were busy fighting in Siam. But the Emperor, with Fuheng's encouragement, made it clear that there would be no compromise. He wanted Burma to surrender completely. His goal was for China to directly rule all Burmese lands. China also sent messages to Siam and Laotian states, telling them of China's plans and asking for their help.

Burma now fully expected another big invasion. King Hsinbyushin brought most of his soldiers back from Siam to face the Chinese. With Burma focused on China, the Siamese resistance took back their capital, Ayutthaya Kingdom, in 1768. They then reconquered all their lands in 1768 and 1769. For Burma, all their hard-won gains in Siam over the past three years were lost. But they could do little about it. The survival of their own kingdom was now at stake.

China's Battle Plan

Fuheng arrived in Yunnan in April 1769 to lead a force of 60,000 soldiers. He studied old battle plans from the Ming and Mongol invasions to create his own. His plan was a three-part invasion through Bhamo and along the Irrawaddy River. One army would attack Bhamo and Kaungton directly. Two larger armies would go around Kaungton and march down the Irrawaddy River, one on each side, towards Ava. These two armies would have war boats with thousands of sailors from the Chinese navy.

To avoid Ming Rui's mistakes, Fuheng planned to protect his supply and communication lines. He also wanted to move slowly and steadily. He avoided going through the Shan Hills jungles to prevent Burmese guerrilla attacks on his supplies. He also brought many carpenters to build forts and boats along the way.

Burma's Battle Plan

For Burma, the main goal was to stop the enemy at the border. They wanted to prevent another Chinese army from reaching their heartland. Maha Thiha Thura was the overall commander. Balamindin again commanded the Kaungton fort. In late September, three Burmese armies were sent to meet the three Chinese armies head-on. A fourth army was formed just to cut the enemy's supply lines. King Hsinbyushin also prepared a fleet of war boats to fight the Chinese boats.

Burma's defenses now included French musketeers and gunners led by Pierre de Milard. Based on Chinese troop movements, the Burmese knew the general direction of the massive invasion. Maha Thiha Thura moved his forces upriver by boat towards Bhamo.

The Invasion Begins

As the Burmese armies marched north, Fuheng, against his officers' advice, decided not to wait until the end of the monsoon season. He wanted to attack before the Burmese arrived. So, in October 1768, during the monsoon season, Fuheng launched the largest invasion yet. The three Chinese armies attacked and captured Bhamo. They then moved south and built a large fort near Shwenyaungbin village, 12 miles east of the Burmese fort at Kaungton. As planned, carpenters built hundreds of war boats to sail down the Irrawaddy.

But almost nothing went as planned. One Chinese army did cross to the western bank of the Irrawaddy, but its commander didn't want to move far from the base. When the Burmese army on the west bank approached, the Chinese retreated back to the east bank. The army on the eastern bank also didn't move forward. This left the Chinese boats unprotected. The Burmese boats came up the river, attacked, and sank all the Chinese boats. The Chinese armies then focused on attacking Kaungton. But for four weeks, the Burmese defended bravely, stopping the Chinese Bannermen from climbing the walls.

Just over a month into the invasion, the entire Chinese invasion force was stuck at the border. As expected, many Chinese soldiers and sailors got sick and started dying in large numbers. Fuheng himself got a fever. Even worse for the Chinese, the Burmese army sent to cut their supply lines succeeded. By early December, the Chinese forces were completely surrounded. The Burmese armies then attacked the Chinese fort at Shwenyaungbin, which fell after a fierce battle. The fleeing Chinese soldiers fell back into the area near Kaungton where other Chinese forces were. The Chinese armies were now trapped between the Shwenyaungbin and Kaungton forts, completely surrounded by Burmese forces.

A Truce is Made

The Chinese commanders, who had already lost 20,000 men and many weapons, now asked for peace. The Burmese generals didn't want to agree. They said the Chinese were trapped like cattle, starving, and could be wiped out in a few days. But Maha Thiha Thura, who had seen Ming Rui's army destroyed at the Battle of Maymyo in 1768, knew that another total defeat would only make the Chinese government more determined to fight.

Maha Thiha Thura reportedly said: "Friends, if we don't make peace, another invasion will come. And when we defeat that, another will come. Our country cannot keep fighting invasion after invasion from China, because we have other things to do. Let's stop the killing, and let our people and their people live in peace."

He told his commanders that fighting China was becoming a problem that could destroy their nation. Compared to China's losses, Burma's losses were smaller, but they were still heavy for their smaller population. The commanders were not convinced. But Maha Thiha Thura, taking responsibility himself and without telling the king, demanded that the Chinese agree to these terms:

- The Chinese would hand over all the sawbwas and other rebels who had fled to China.

- The Chinese would respect Burma's control over the Shan States that had always been part of Burma.

- All prisoners of war would be released.

- The Chinese Emperor and the Burmese King would become friends again, sending letters and gifts to each other regularly.

The Chinese commanders agreed to these terms. At Kaungton, on December 13 or 22, 1769, under a special hall, 14 Burmese and 13 Chinese officers signed a peace treaty (known as the Treaty of Kaungton). The Chinese burned their boats and melted down their cannons. Two days later, the starving Chinese soldiers marched sadly away up the Taping River valley. Thousands of them died from hunger in the mountain passes.

What Happened Next

In Beijing, the Qianlong Emperor was not happy with the treaty. He didn't accept his commanders' explanation that the exchange of gifts meant Burma was giving up. He did not allow the return of the sawbwas or other rebels, nor did he allow trade to restart between the two countries.

In Ava, King Hsinbyushin was furious that his generals had made a treaty without his permission. He tore up his copy of the treaty. Knowing the king was angry, the Burmese armies were afraid to return to the capital. In January 1770, they marched to Manipur, where a rebellion had started because of Burma's troubles with China. After a three-day battle, the Manipuris were defeated, and their king fled. The Burmese put their own chosen ruler on the throne and returned home. The king's anger had cooled down; after all, his generals had won battles and saved his throne. Still, the king sent Maha Thiha Thura, the brave general whose daughter was married to the king's son, a woman's dress to wear. He also sent him and other generals away to the Shan States and refused to see them. He also exiled ministers who tried to speak up for them.

Even though the fighting stopped, it was an uneasy peace. Neither side fully followed the treaty. Because China didn't return the sawbwas, Burma didn't release the 2,500 Chinese prisoners of war, who were settled in Burma. China lost some of its most important border experts, including Yang Yingju, Ming Rui, Aligun, and Fuheng (who later died of malaria in 1770). The war cost China a lot of money. Still, the Emperor kept many soldiers near the border for about ten years, hoping to fight again. He also banned trade between the two countries for two decades.

For years, Burma worried about another Chinese invasion. They kept many soldiers along the border. The war caused many deaths for Burma (compared to its population size). This and the need to guard the northern border made it hard for Burma to fight in Siam again. It would be five more years before Burma sent another army to Siam.

It took twenty years for Burma and China to start talking again in 1790. This happened because Shan nobles and Chinese officials in Yunnan wanted trade to restart. For the Burmese, then under King Bodawpaya, the talks were between equals. They saw the exchange of gifts as normal diplomatic manners, not as paying tribute. But for the Chinese, all these diplomatic visits were seen as Burma paying tribute. The Emperor saw the return of relations as Burma giving up and claimed victory. He included the Burma campaign in his list of Ten Great Campaigns.

Why This War Was Important

Changes to Borders

Burma's successful defense helped create the border we see today between the two countries. The border was still not perfectly marked, and some areas were influenced by both sides. After the war, Burma kept control of Koshanpye, the nine states above Bhamo. Burma also had authority over southern Yunnan borderlands, as far as Kenghung (today's Jinghong, Yunnan), until the British took over Burma in 1886. China also had some control over border areas, including parts of today's northeastern Kachin State. Overall, Burma was able to push the border back to where it was before China tried to take more control in the 1730s.

However, the war also forced Burma to leave Siam. Burma's victory over China is seen as a great moral victory. Historian G.E. Harvey wrote that Burma's other wins were against countries like Siam, which were similar in power. But this victory was against a huge empire. He called the Sino-Burmese war "a righteous war of defense against the invader."

Big Picture Changes

The main winners of the war were the Siamese. They used Burma's absence to take back their lost lands and independence. By 1770, they had regained most of their territory from before 1765. Only Tenasserim remained under Burmese control. Burma was busy with the Chinese threat and recovering from losing many soldiers. So, King Hsinbyushin left Siam alone. In the decades that followed, Siam became a powerful country, taking over other areas like Lan Na, the Laotian states, and parts of Cambodia.

From a wider view, China's Qing dynasty and the Qianlong Emperor, who had never lost a war before, now had to accept that even their power had limits. A historian of Chinese military history, Marvin Whiting, believes that Burma's success probably saved other countries in Southeast Asia from being taken over by China.

Military Lessons

For China's Qing dynasty, the war showed the limits of their military power. The Emperor first blamed his Green Standard Army for the first two losses. But he later admitted that his Manchu Bannermen were also not well-suited for fighting in Burma compared to places like Xinjiang. Even though China sent 50,000 and 60,000 soldiers in the last two invasions, the Chinese commanders didn't have good maps or information about the invasion routes. They had to use maps that were hundreds of years old. This made their supply and communication lines easy targets for Burmese attacks. It also allowed their main armies to be surrounded in the last three invasions.

Burma's tactic of destroying everything useful (called a scorched earth policy) meant that the Chinese armies were vulnerable when their supplies were cut. Perhaps most importantly, Chinese soldiers were not used to the tropical climate of Burma. In the last three invasions, thousands of Chinese soldiers got sick with malaria and other tropical diseases, and many died. This canceled out China's advantage of having more soldiers. It allowed the Burmese to fight the Chinese armies head-on towards the end of the campaigns.

The war is seen as the peak of the Konbaung military power. Historian Victor Lieberman wrote that these victories over Siam (1767) and China (1765–1769) at almost the same time showed amazing energy, unmatched since King Bayinnaung. The Burmese military proved they could fight a much stronger enemy. They used their knowledge of the land and weather to their advantage. The Battle of Maymyo is now studied as an example of how foot soldiers can fight a larger army.

However, the war also showed the limits of Burma's military power. The Burmese learned they couldn't fight two wars at once, especially if one was against the world's largest military. King Hsinbyushin's risky decision to fight on two fronts almost cost his kingdom its independence. Also, Burma's losses, though smaller than China's, were heavy for their much smaller population. This limited their military power for other fights. The Konbaung's military strength would not grow much in the following decades. They didn't make progress against Siam. Their later conquests were only against smaller kingdoms to the west, like Arakan, Manipur, and Assam.

See also

- Mongol invasion of Burma

- Ten Great Campaigns

- Burmese–Siamese War (1765–1767)

- Battle of Ngọc Hồi-Đống Đa

- First Anglo-Burmese War

Images for kids

-

Myanmar (缅甸国) delegates in Peking in 1761, at the time of the Qianlong Emperor. 万国来朝图

-

The Qianlong Emperor's bannermen

-

Qing flotilla

-

A Burmese war-boat on the Irrawaddy River