Skull Valley Indian Reservation facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 134 enrolled members, 15-20 living on reservation |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Shoshoni-Gosiute dialect, English | |

| Religion | |

| Native American Church, Mormonism, | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Western Shoshone peoples, Ute people |

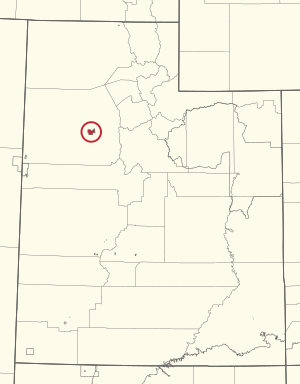

The Skull Valley Indian Reservation (in the Gosiute dialect: Wepayuttax) is a special area of land in Tooele County, Utah, United States. It is about 45 miles (72 km) southwest of Salt Lake City. This land is home to the Skull Valley Band of Goshute Indians of Utah. This group is a federally recognized tribe, which means the U.S. government officially recognizes them as a Native American nation with its own government. In 2017, the tribe had 134 registered members, with about 15 to 20 people living on the reservation.

Contents

The Land of Skull Valley

The reservation covers about 28 square miles (73 square kilometers) of land. It is located in the eastern part of Tooele County. The land is next to the Wasatch-Cache National Forest in the Stansbury Mountains. The reservation is in the southern part of Skull Valley, with the Cedar Mountains to the west. One former tribal leader, Leon Bear, once called their land a "beautiful wasteland."

History of the Goshute People

The Goshute people have lived in this area for a very long time. They have experienced many floods over the years. For example, in 2013, after a big fire, a strong rainstorm caused a lot of flooding and mudslides. Workers used special barriers and sandbags to help protect the area. More floods happened later, damaging the drinking water system. Efforts were made to stabilize the land and plant grass to prevent future problems.

Early Encounters with Europeans

The Goshute people first met European explorers in 1776, when Spanish missionaries arrived. Later, fur trappers and explorers like Jedediah Smith came through their lands. In the 1830s, Spanish slave traders began taking Goshute women. More regular contact started in 1847 when Mormon settlers arrived. These settlers often called the Goshute people "diggers" and described them in ways that showed they didn't understand their way of life.

Mormon settlers also brought diseases like smallpox and measles, which the Goshute people had no protection against. By 1849, settlers entered Tooele Valley and started new towns. The leader, Brigham Young, asked the U.S. government to move all Native Americans in Utah to reservations where white settlers would not live. As more settlers arrived, they took over the best Goshute lands near streams and canyons. This forced the Goshute people into more difficult and dry areas. This led to conflicts, with both Goshute raids and Mormon attacks resulting in deaths.

The Pony Express and Conflicts

In 1860, the Pony Express, a mail service, built stations right through Goshute land. The Goshute people sometimes raided these stations, taking supplies and occasionally clashing with Europeans. To protect the Pony Express route, the military was called in. This led to the Goshute war from 1860 to 1863. During this war, at least 100 Goshute people and 16 white settlers died.

On October 12, 1863, the Goshute band signed a treaty with the U.S. government. However, they did not give up their land. The U.S. government tried several times to move the tribe to another reservation, but the Goshutes refused. They were often ignored and not given the support they needed.

Establishing the Reservation

In 1912, an official order created an 80-acre reservation in Skull Valley. President Woodrow Wilson later expanded this land to about 18,000 acres in 1917 and 1918. Even after this, the government still tried to move the Skull Valley band to a different reservation between 1936 and 1942, but they remained on their land.

Tribal Government Today

The Skull Valley Goshute tribe is led by a three-person executive committee. In 2000, 31 people lived on the reservation. Today, the tribe has 134 members, with about 15 to 20 living on the reservation.

The tribe has had different leaders over the years. Lawrence Bear was a tribal chairman, and later his nephew, Leon D. Bear, also served as chairman. After some challenges, Lawrence Bear became chairman again in 2007. In 2010, Lawrence Bear passed away. In 2011, his daughter, Lori Bear Skiby, was elected as the chairwoman. She worked to create a formal court system for the tribe in 2013.

Environmental Concerns

The Skull Valley Indian Reservation is surrounded by many industrial and military sites. This has raised concerns about the environment and the health of the tribal members.

Nearby Facilities

The areas around the reservation have been used for various purposes, including:

- A hazardous waste landfill, where dangerous trash is buried.

- A facility that stores and treats nerve gas, which are very harmful chemicals.

- Two incinerators that burn hazardous waste.

- A magnesium plant that releases a lot of chlorine gas.

- The Intermountain Power Plant, which releases toxic chemicals into the air.

The U.S. government has also tested biological weapons near Skull Valley. Some experts believe that having so many industrial sites near the reservation is a form of environmental racism. This means that minority groups, like the Goshute tribe, are unfairly affected by pollution and dangerous activities. This is especially concerning because over 30% of the tribe's members are children.

Dugway Proving Ground and the Sheep Incident

The United States Army tests very toxic chemicals, like the VX nerve agent, at its Dugway Proving Ground facility. This facility is located right next to the Skull Valley Indian Reservation.

On April 12, 1968, a sad event known as the Dugway sheep incident occurred. About 6,000 sheep belonging to the Skull Valley Goshute tribe died after being exposed to the deadly VX agent. This happened during a test where a plane sprayed the agent. The plane climbed too high, and some of the agent leaked out. It then rained and snowed, and it is thought that the rain and snow carried the agent. When the sheep drank the water and licked the snow, they showed signs of VX poisoning.

The Army has never officially admitted fault for this incident. However, a report from 1970 showed clear evidence of nerve gas. Because of the thousands of contaminated sheep, the tribe has not been able to raise animals on their land since then. This has made it harder for the reservation to earn money from its land. It might also be why the tribe has considered other ways to make money, like waste disposal or nuclear storage.

The Dugway Proving Ground also conducts experiments with viruses about 14 miles (23 km) from the reservation. Since the details of these experiments are not widely known, it is hard to know what future health risks they might pose to the people living on the reservation.

Debate Over Nuclear Waste Storage

The idea of storing nuclear waste on the reservation has been a big topic of discussion for many years, causing different opinions within the tribe.

In 1987, the U.S. government created an office to help arrange deals for storing nuclear waste. In 1991, this office offered money to Native American tribes in exchange for agreements to store high-level nuclear waste on their land. The Skull Valley Band of Goshutes received grants to study this idea. By 1993, they were one of only a few tribes still interested.

Even though the government office closed in 1994, a group of power companies continued to talk with the Skull Valley Band about storing nuclear waste. In 1996, the tribal chairman, Leon Bear, signed a first agreement to store 40,000 tons of nuclear waste on the reservation. The companies said this would be a temporary solution until a larger storage site in Nevada was ready. However, the Nevada project faced many problems and was eventually stopped.

This nuclear waste agreement was very controversial. Some tribal members supported the project because it would bring a lot of money to the tribe. Others, however, strongly opposed it, calling it environmental racism. Many people outside the tribe also objected, including Utah's government leaders, environmental groups, and other Native American tribes.

In 2006, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) approved a license for the project. However, the State of Utah challenged this in court. Later, a law was passed that made it very difficult to build a railway to bring the nuclear waste to the reservation. This law was supported by the U.S. Air Force, which uses Skull Valley for flight paths. They were concerned about the risks of a nuclear waste site in an area where a plane crash could release radiation.

Finally, in December 2012, after many years of challenges and legal battles, the project was officially stopped. The company involved asked for their license to be ended. This meant the nuclear waste storage project would not happen on the Skull Valley Indian Reservation.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |