Slave labor on United States military installations 1799–1863 facts for kids

In the early 1800s, it was common to see enslaved people working at United States military bases. The U.S. government, through its different departments, often used enslaved Black people for labor. In fact, the U.S. military was the biggest federal employer of enslaved people who were rented or leased from their owners before the Civil War.

In 1816, someone visiting the Washington Navy Yard noted that a blacksmith, Benjamin King, said it cost about 27 cents a day for an enslaved worker. He also mentioned how profitable this was. The Navy paid 80 cents a day for Black workers, while white blacksmiths earned $1.81 a day. Further south, at the Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard in 1830, civil engineer Loammi Baldwin reported how much money was saved by using enslaved people. He compared the cost of free white stone masons with enslaved Black workers. Enslaved workers cost 72 cents a day, while white stone masons were paid $2.00 a day. Lady Emmeline Stuart Wortley, an English writer, visited in the late 1840s. She saw many enslaved people at the Washington Navy Yard. She wrote, "We saw a sadder sight after that, a large number of slaves, who seemed to be forging their own chains, but they were making chains, anchors, &c., for the United States Navy."

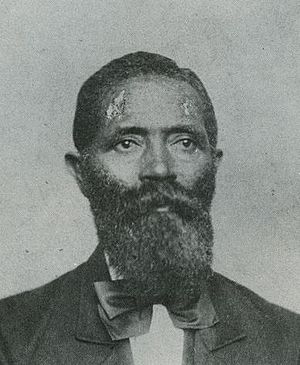

George Teamoh (born 1818), who was once enslaved, worked as a ship caulker and carpenter. He toiled at the Norfolk Navy Yard and Fort Monroe in the 1830s and 1840s. Teamoh later wrote about his years of forced labor at federal shipyards and forts. He said, "The government has patronized, and given encouragement to Slavery to a greater extent than the great majority of the country has been aware. It had in its service hundreds if not thousands of slaves employed on government works."

Today, the history of the U.S. government renting enslaved people for federal bases is not studied as much as other parts of slavery. Historians have mostly focused on the large plantations in the South. However, in the early 1800s, the government's use of enslaved labor was often discussed publicly. Both slaveholders and critics shared strong opinions. Recent studies confirm that Black people, both enslaved and free, were a very important source of labor for military bases.

Contents

- Early Use of Enslaved Labor by the Government

- Keeping Records of Enslaved Workers

- Washington Navy Yard

- Norfolk Navy Yard

- Norfolk Naval Hospital

- Pensacola Navy Yard

- Fort Zachary Taylor

- Fort Jefferson

- Government Rules and Enslaved Labor

- Public Complaints and Resistance

- "Gentleman's Agreements"

- Discipline and Control

- Resistance and the End of Slavery

Early Use of Enslaved Labor by the Government

The way the federal government hired workers was similar to society at the time. This was especially true in the Southern states and territories where slavery was common. The government's use of enslaved labor started early. In 1800, nearly 40% of white households in Washington, D.C., owned enslaved people. Many early visitors, like Massachusetts Congressman Thomas Dwight (politician), noticed this. In 1803, Dwight complained that people in this area loved owning enslaved people more than anything else. He was surprised that even poor people invested in enslaved individuals. He noted they made their money back by "hiring out" these enslaved people.

In the new District of Columbia, hiring out enslaved people was a long-standing tradition. It began in 1792 when the District of Columbia Board of Commissioners started hiring workers for public buildings. They quickly decided to hire enslaved laborers too. On average, the Commissioners hired 50 to 100 enslaved people each year. The Commissioners, who all owned enslaved people, saw this as a way to keep free workers' wages low. In the 1790s, owners in the District were paid $60 to $70 a year for renting their enslaved people. This was the same wage paid to unskilled white workers. The Commissioners' decision to hire Black people caused no public comment in 1792 because slavery was legal. This pattern continued with new federal naval shipyards. These included the Washington Navy Yard (1799), Norfolk Navy Yard (1801), and Pensacola Navy Yard (1826). Enslaved labor was also used at U.S. Army bases like Fort Zachary Taylor (1845) and Fort Jefferson (1846).

Keeping Records of Enslaved Workers

Finding complete information about civilian workers at military bases in the middle and southern states is often hard. The federal government rarely owned enslaved people directly. Instead, they leased or hired them from local slaveholders. Historians have noted that these hiring agreements were often not written down. They were more like "gentleman's agreements." This makes it difficult to find records.

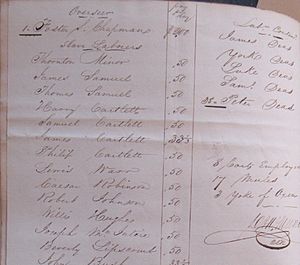

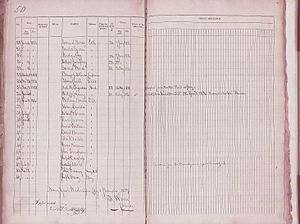

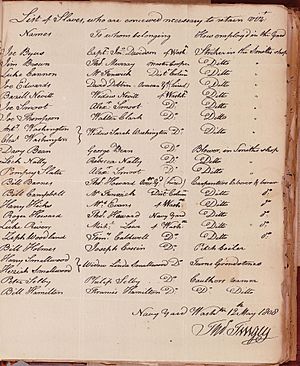

Early employee records, like payrolls, were mainly for money. They usually did not say if a worker was Black or enslaved. An example that does is the 1829 payroll for the Pensacola Navy Yard. Most of these records are still at the National Archives in Washington D.C. They have not been put online yet. There are big gaps in the records. For instance, payrolls for the Washington Navy Yard before 1840 are only available for a few years. Only some of these lists clearly show enslaved employees and their owners.

As objections to enslaved labor grew, especially after 1820, military officers often listed enslaved people as "ordinary seamen" or "common laborers." This helped them avoid being questioned by Congress. Many record keepers at these bases owned enslaved people themselves. Other information comes from letters written by base commanders. These letters answered questions from the Secretaries of the Army and Navy about hiring Black workers. Finally, personal stories from people like Charles Ball, Michael Shiner, George Teamoh, and Thomas Smallwood tell us what life was like for enslaved people on federal military bases.

Because of these record problems, we may never know the exact number of enslaved people who worked on military bases. However, the following sections give an idea of how many enslaved workers were at some key locations.

The Washington Navy Yard, started in 1799, was the first federal naval base to use enslaved labor. Many of the Navy's rules about hiring Black workers began here. Some of the same slaveholders who rented enslaved people to the District of Columbia Commissioners later rented them to this new shipyard. These rules became examples for other federal shipyards and military bases. For the first 30 years of the 1800s, it was the main employer of enslaved African Americans in Washington, D.C. Their numbers quickly grew. By 1808, they made up one-third of all workers. The Navy had quickly come to depend on enslaved labor. On May 18, 1808, Captain John Cassin wrote to the Secretary of the Navy, Robert Smith. He asked to keep the enslaved workers.

Captain Cassin did not want to stop using enslaved labor. This shows how common it was to rent enslaved people for different jobs. They worked in shops and on naval ships as sailors, cooks, and laborers. The Navy Yard's creation, along with the hiring practices of the District Commissioners, likely encouraged small slaveholders to buy more enslaved people. The 1808 Navy Yard records show that renting enslaved people was profitable. Naval officers could earn extra money by collecting the wages of their enslaved "servants." Commodore Thomas Tingey supported this practice. He asked Secretary Smith to continue this "customary indulgence." During this time, the Navy Yard was a popular place to rent out and sell enslaved people. But it also became a place where enslaved people resisted.

As early as 1815, the Board of Navy Commissioners (BNC) complained about "unmanageable slaves." Many of these "unmanageable" enslaved people were runaways from the Navy Yard. In 1812, David Davis, a young Navy blacksmith helper, tried to escape for the second time. He ran towards Baltimore. Similarly, another "servant," John Howard, who was enslaved by Commandant Thomas Tingey, fled north to Boston in 1819. There, he was caught by slave catchers. A group of African Americans bravely tried to free him. Years later, in 1825, Nathan Brown, a young Navy Yard anchor smith, ran away to the new Black Republic of Haiti.

Because it was close to many free Black people and some white supporters, some enslaved workers, like Michael Shiner at Washington Navy Yard, could use the legal system to challenge their enslaved status. A key case was that of Joe Thompson vs Walter Clark in 1818. Joe Thompson, a blacksmith's helper at the Navy Yard, won a long fight for his and his family's freedom in 1818. His lawyer was Francis Scott Key.

The Board of Navy Commissioners became worried about naval officers and senior civilians using their enslaved people at naval bases. So, on March 17, 1817, they sent a notice to all naval shipyards. It banned the employment of all enslaved and free Black people. The notice said, "no Slaves or Negroes, except under extraordinary Circumstances, shall be employed in any navy yard." On the same day, Board President Commodore John Rodgers told Commodore Thomas Tingey that only white employees should replace the Black workers. However, such orders limiting Black employment were often followed by exceptions. Officers and slaveholders would ask the Secretary and the Board to allow enslaved labor to continue.

When Commodore Isaac Hull took command of the Washington Navy Yard in 1829, he found enslaved labor was still common. Hull, from Connecticut, realized that white people in the South would not do certain "menial tasks." He also saw that officers' "servants" were Black. So, he bought an enslaved man named John Ambler, who was then put on the Navy Yard payroll. Hull was later told that enslaved people belonging to naval officers should not be employed except as servants. Hull replied, "I fear we could not find a set of men white or black, or even slaves belonging to the poor people outside the yard to do the work now done in the anchor shop... I have considered them the hardest-working men in the yard." Yet, in 1830, only three of the 16 Black workers listed by Isaac Hull were free. The rest were enslaved, mostly by the officers and high-ranking civilians of the Yard itself.

The 1835 Washington Navy Yard labor strike showed the long-standing racial tensions at the shipyard. White workers feared that competition from enslaved and free Black people would lower their wages. The strike quickly turned into the Snow Riot. This event showed that racism and slavery had weakened the workers' ability to bargain. As day laborers, the striking workers suffered because they lacked strong organization and money. Most importantly, their strike and the riot showed how racism harmed the workforce. White workers blamed their own difficult economic situation on free and enslaved African Americans. The strike left a deep racial mistrust that lasted for many years. For the next century, the history of the 1835 strike and the Snow riot was often ignored in official histories.

The number of enslaved workers slowly decreased over the next 30 years. However, free and some enslaved African Americans remained important workers. Records show enslaved labor, called "servants," still working in the blacksmith shop as late as August 1861. A key difference at the Washington Navy Yard was that many slaveholders were senior naval officers and civilians who worked there. While most Black people at the Navy Yard were enslaved, a few free Black people, especially in the early years, earned good wages.

The federal government bought the Norfolk Navy Yard from Virginia in 1801. This new federal shipyard was like the old State of Virginia Naval Yard, where enslaved labor was common. These practices continued until the Civil War. The Norfolk Navy Yard used many enslaved people. These enslaved laborers provided their owners with a steady income. Sometimes, slaveholders openly put their enslaved workers on the federal payroll. For example, in 1830, Navy Yard Commandant, Commodore James Barron, listed two enslaved women, Lucy Henley and Rachel Barron, on the shipyard payroll as "ordinary seamen." He then collected their wages.

We can get an idea of the number of people involved from a letter written on October 12, 1831. Commodore Lewis Warrington wrote to the Board of Navy Commissioners. He was responding to complaints from white workers and the recent slave rebellion led by Nat Turner. His letter tried to calm the Board. He also replied to the dry dock's stonemasons, who had quit. They accused the chief engineer, Loammi Baldwin, of unfairly hiring enslaved labor instead of them.

Warrington wrote that about 246 Black people worked in the Yard and Dock. He said they would soon discharge 20, leaving 126. He added that the use of Black workers would decrease further. He said that once the work was finished, there would be no need for them.

On March 30, 1839, Secretary of the Navy James K. Paulding ordered the Commandant of Norfolk Navy Yard, Lewis Warrington, to fire all enslaved workers. This included those belonging to "officers of the Navy, Marines & to persons holding appointments or employment under the Department of the Navy." Secretary Paulding and later leaders found that this profitable practice was a big part of the Southern economy. Many officers and senior civilians quietly supported it.

Commodore Warrington's response on June 21, 1839, shows how much the shipyards relied on enslaved labor. He stated that no enslaved person in the Yard was owned by a commissioned officer. However, many were owned by the "Master Mechanicks & workmen of the Yard." He explained that enslaved people were not allowed to do mechanical work. This work was "reserved for the whites" to keep a "proper distinction." He also said that if enslaved people were fired, it would be a big loss for their owners. This was because it would be hard to rent them out elsewhere.

George Teamoh, who was enslaved and worked at the famous Norfolk Navy Yard Dry Dock number 1, wrote about his experience. He said, "I was for sometime water bearer in the above Dock while it was in building. Helped dock the first ship that berthed there [USS Delaware], I have worked in every Department in the Navy Yard as a laborer, and this during very many long years of unrequited toil, and the same might be said of vast numbers, reaching to thousands of slaves who were worked, lashed and bruised by the United States Government..." Teamoh remembered that in the 1840s at Norfolk Navy Yard, it was dangerous for any enslaved worker to speak to white people. He said, "Slavery was so interwoven at that time in the very ligaments of the government that to assail it from any quarter was not only a herculean task, but one requiring great consideration, caution and comprehensiveness."

Even ten years later, despite complaints from white workers, the Norfolk Navy Yard continued to hire many enslaved people. By 1848, almost one-third of the 300 workers at Norfolk Navy Yard were hired enslaved people. Many of these men worked as laborers and skilled workers. Records from 1850 show that Black workers were used only as laborers in work groups, supervised by white overseers.

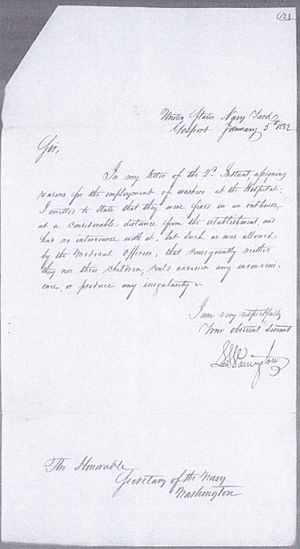

Throughout the early 1800s, the Norfolk (Gosport) Naval Hospital used many enslaved people. Enslaved Black people worked at the hospital as helpers, nurses, cooks, laundresses, and gravediggers. Records often mention enslaved people by their job or a familiar name, like "Capt. Warrington’s (Serv.) Henry" or "Commodore Barron’s servant 'Fanny the washerwoman'." Enslaved women and children lived in an "outbuilding" on the hospital grounds. Sometimes, their enslaved status was clearly stated. For example, in a 1825 case file, an enslaved laundress named Fanny Ballott was "discharged from the Hospital and send to her owner."

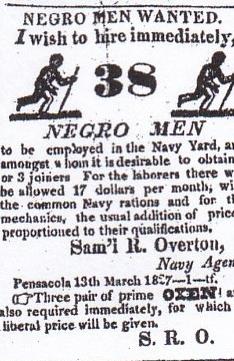

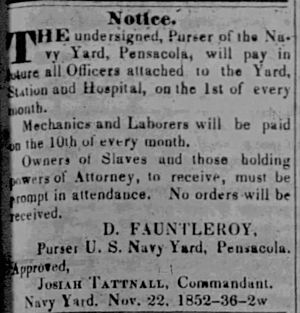

The Pensacola Navy Yard was started in April 1826. It was chosen for its great harbor, nearby timber for shipbuilding, and its location near the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean. The West India Squadron patrolled these waters to stop piracy and the international slave trade. Ironically, this early Navy Yard was mostly built and kept running by enslaved labor. The Pensacola Navy Yard, the seventh federal shipyard, was built in Florida. Navy Captains William Bainbridge, Lewis Warrington, and James Biddle picked the site. Pensacola did not have enough workers to lay bricks, bend iron, and haul lumber. So, the government hired hundreds of enslaved people. They leased them from local slave-owners.

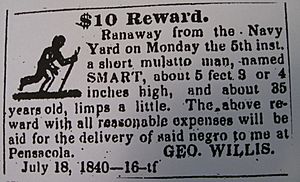

Even early on, a monthly list from May 1829 shows that over one-third of the workforce was enslaved labor. This list, which shows names, jobs, and wages for 87 workers, specifically names 37 as "slave laborers." This early list is rare because it clearly notes the enslaved status. Here, like at other naval shipyards, civilian employees like Navy Agent George Willis leased their enslaved people to the Navy.

To help local slaveholders, the Pensacola Navy Yard hospital provided emergency medical care to enslaved laborers. In 1838, Dr. Solomon Sharp, who owned enslaved people himself, questioned why enslaved Navy Yard workers received free medical treatment. He asked the Secretary of the Navy, Mahlon Dickerson. Dickerson replied that it was "not deemed expedient to change the practice." The Navy Yard also protected slaveholders from losing their "property." For example, in 1838, the Navy Yard approved claims for payment to three slaveholders. Their enslaved employees had died accidentally by drowning.

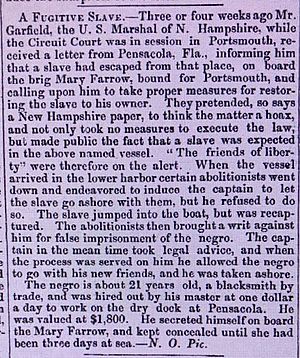

Slavery remained a key part of the Pensacola Navy Yard workforce until the Civil War. As late as June 1855, the Pensacola Navy Yard payroll listed 155 enslaved employees. Historian Ernest Dibble concluded that in Pensacola, the military was the most important force in creating the local economy. It was also the biggest influence on the spread of slavery there. Pensacola's location and isolation made it very hard and dangerous for enslaved people to escape. Historian Matthew J. Clavin noted only one documented case of a successful escape. This was Adam, a 21-year-old blacksmith from the Pensacola Navy Yard. He managed to reach the northern United States or Canada.

Fort Zachary Taylor

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers started building Fort Zachary Taylor in June 1845. Most of the skilled workers were Irish and German immigrants. They were recruited in New York after arriving from Europe. However, the very hard labor was done by enslaved people from Key West. Their owners rented them out under contract. Angela Mallory, whose husband Stephen Mallory later became the Confederate Secretary of the Navy, was one of the local citizens who found this arrangement profitable. Slave hiring at Fort Taylor was usually part-time. About two-thirds of the 414 enslaved people who worked there did so for 12 months or less. A recent study of slave hiring by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers found that slave hiring from 1845–1860 grew stronger. This happened because of the federal government's support.

Fort Jefferson

Construction of Fort Jefferson, named after President Thomas Jefferson, began on Garden Key in December 1846. The Army hired civilian carpenters, masons, general laborers, and enslaved people from Key West to help build the fort. By August 1855, 233 white contract laborers were employed. But enslaved people "were the backbone of the labor gang," according to Albert Manucy. The workforce in the early years was mostly enslaved people from Key West. Records from Fort Jefferson from October 1860 to June 1861 list 16 to 36 enslaved people. They worked as laborers, masons, and cooks. Their total cost was $4,877.00. Although the fort was built for 30 years, it was never finished. This was mainly because new weapon technology made it outdated by 1862.

Government Rules and Enslaved Labor

Military rules about enslaved labor were not very organized. They were more a mix of different ideas than a clear plan. These rules usually followed those first used in 1792 by the District of Columbia Board of Commissioners. They were for building the U.S. Capitol and the White House. In most cases, the federal government did not buy enslaved people. Instead, they leased or rented them from private individuals in nearby communities. These agreements between military officials and slaveholders were often spoken, not written. They were called "gentleman's agreements." These agreements helped hide the renting of enslaved people and avoid public attention.

One example from the Navy Department is an 1824 note to Commodore Thomas Tingey. It confirms that a local slaveholder sent his enslaved man to the Washington Navy Yard. He went directly to master blacksmith Benjamin King to ask for work. The note shows how informal these arrangements could be.

Two written agreements for enslaved labor exist from the Army Corps of Engineers. They are dated May 12, 1829, and March 25, 1830. The 1830 agreement was between the Corps and a local slaveholder. It was for his enslaved skilled workers and laborers to do masonry and digging. The agreement was a "Memorandum of a verbal agreement."

To ease slaveholders' worries about injury to their "property," the Secretary of the Navy made a big promise in 1813. This was to include enslaved workers in the emergency medical care at the Washington Naval Hospital. This was later extended to other naval hospitals. The rule said that if an enslaved person was injured at work, their owner would pay a "reasonable compensation" for medical care from their wages. If the injury lasted, the owner had to remove the enslaved person from the hospital. The shipyard followed a rule set by the District of Columbia Commissioners in 1792. They provided medical help to enslaved laborers working on the Capitol. Naval Hospitals treated many different illnesses. Records show enslaved workers were treated for injuries and sicknesses like rheumatism and fever. Both white and Black patients were housed in the same facility. Enslaved workers like Michael Shiner were listed as patients. The Navy later extended this important rule to slaveholders at Norfolk and Pensacola shipyards.

The military never owned enslaved people. Instead, they rented or leased them from local slaveholders. This meant the military got all the benefits of enslaved labor with few downsides. Without formal contracts, military officers provided control and direction. Slaveholders were responsible if the enslaved person was seriously injured or died. If an enslaved person ran away, the owner had to find them or accept the loss. This system gave the military efficient and skilled labor.

Modern historians have studied whether slavery was profitable and if it lowered the wages of free workers. They have found different answers. Before the Civil War, the economic argument for enslaved labor on federal shipyards was often supported. At the Washington Navy Yard, master blacksmith Benjamin King, who owned enslaved people, wrote in 1809 to Commodore Thomas Tingey. He clearly argued for enslaved labor. He said Black enslaved men were better workers than white free men. He noted they were easier to control and worked harder. He also said they stayed longer after learning a skill. In 1817, master plumber John Davis also argued for enslaved labor. He said, "we found by long experience that Blacks have made the best Strikers in the execution of heavy work & are easily subjected to the Discipline of the Shop - & less able to leave us on any change of wages."

While not always stated so directly, the economics of hiring enslaved people were important to the Army Corps of Engineers and the Board of Navy Commissioners. However, white workers challenged this support. They often feared economic competition from enslaved labor. Abolitionists also saw slavery as morally wrong. Most critics of hiring enslaved people on federal bases gave economic reasons. One writer called the BNC "Unfeeling men! You have reduced the wages of this yard." Another writer in 1825 said that hiring enslaved people was "injurious to the interest of the city."

Historian Linda Maloney studied federal shipyard wages. She found that white workers' fears had some economic basis. Enslaved labor did have a "cooling" effect on free wages. Maloney found that laborers at the mostly white Charlestown Naval Yard in Massachusetts earned $1.00 a day or more. But workers at the Washington Navy Yard, both white and Black, earned only $0.72. In 1846, the Commandant of the Norfolk Navy Yard, Charles W. Skinner, told Secretary of the Navy John Y. Mason that wages for skilled carpenters were $1.75 in Baltimore but $1.50 in Norfolk. He blamed this on few skilled workers and "the work being generally performed by Negros."

We have some specific wage data. In 1821, Commodore Thomas Tingey provided wage scales for different shipyard jobs from 1801–1820. However, he did not include data for enslaved people. The data shows a big drop in workers' income. For example, in 1801, a painter earned $1.56 a day. In 1820, a painter earned only $1.52–$1.32. Ship caulkers' wages dropped even more. Tingey reported they were paid $1.81 in 1810, but their wages fell to $1.44 by 1820. Shipyard laborers, who were at the bottom, earned $0.85–$0.75 in 1810. A decade later, their wages were $0.80–$0.68. Ship caulkers and laborers, jobs with many Black workers, saw big declines. Since these figures are for free labor, we can guess that wages for enslaved labor were much lower.

Similarly, historian Robert Starobin's study of the Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard shows that in the 1830s, enslaved people produced as much as white workers for two-thirds the cost. He reported that blacksmith helpers earned 72 to 83 cents a day, averaging about 72 cents. White workers' daily wages ranged from $1.68 to $1.73. Even if you added 30 cents a day for the enslaved workers' upkeep, there was still a big wage difference.

However, competition from enslaved people was not the only reason for low wages in Washington or Norfolk. Wages were low because there were too many low-skilled white workers. These workers had little power because skilled workers saw them as rivals, not allies. So, they were not included in workers' organizations. While enslaved labor decreased after the 1835 strike at the Washington Navy Yard, in Florida and Virginia, using enslaved labor became normal. This was because it was profitable for both the government and the slave owners.

Public Complaints and Resistance

In the late 1820s, public complaints and requests to end enslaved labor on federal bases increased a lot. This was seen in the growth of groups like the American Colonization Society and the abolitionist movement. During this time, many flyers condemning the sale and keeping of enslaved people in the District of Columbia appeared. At the same time, the campaign for Congress to end slavery in the nation's capital became widespread. Abolitionists tried to get public support by sharing stories of enslavement and freedom from former enslaved people. One of the earliest was by Charles Ball, a former enslaved shipyard worker at the Washington Navy Yard. He fought in the War of 1812. His book, A Narrative of the life and adventures of Charles Ball, a Blackman, was published in 1837. Ball's story was one of the first and became a model for many others.

The increase in enslaved labor quickly worried white skilled workers and laborers. At the Washington Navy Yard and Norfolk Navy Yard, skilled workers strongly disliked any idea of Black people becoming apprentices in skilled trades. From time to time, public anger also rose against naval officers who rented their enslaved people to the government. One critic complained, "Another officer hires a negro for 60 dollars per annum; and lets him to superior officer for one dollar per diem. A fine speculation; but public losses are private benefits." One resident of the District said that hiring enslaved people at the shipyard prevented white men from taking jobs there. This was because "whites feel it to be a degradation." White foremen expected all Black workers to be respectful. But over time, Black workers began to speak out and question the fairness of their pay. In 1812, a group of white blacksmiths complained to the Secretary of the Navy. They said they resented Black people they saw as "insolent."

They wrote that they were "subjected to the insolence of negroes employed in the Navy Yard." They felt there was no way to stop the "misconduct of blacks." They also said that one of their group was threatened with being fired for hitting an enslaved person who had "grossly misbehaved." They believed rules should be made to control Black workers and only hire those who were "orderly and absolutely necessary."

Fear of Black employment was present at all federal shipyards. In 1843, the Richmond Whig protested "the employment of slaves to the exclusion of white labor in the Norfolk Navy Yard." It said that enslaved labor should only be used by the government as a last resort. This was also true for shipyards in the North. As late as 1862, Admiral Hiram Paulding publicly stated in the New York Times that no African American was ever employed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, as far as he knew. Most white skilled workers and laborers saw free Black people as a direct threat to their jobs. They pushed for Black people to be excluded from all skilled trades and supervisory roles.

The Board of Navy Commissioners (BNC) seemed most concerned about the number of officers and master mechanics who rented their enslaved people to the Navy. The BNC sometimes took strong steps to limit the number of Black workers. On March 17, 1817, they sent a notice to all naval shipyards. It banned the employment of all Black people. The notice stated, "no Slaves or Negroes, except under extraordinary Circumstances, shall be employed in any navy yard." On the same day, BNC President Commodore John Rodgers told Thomas Tingey that only white employees should replace the Black workers. On April 3, 1817, a similar reminder was sent to the Norfolk Naval Shipyard. It ordered the "employment of none but white men in the Yard." However, these orders were often followed by exceptions. Officers and slaveholders would pressure the Secretary and the Board to allow enslaved labor to continue.

"Gentleman's Agreements"

In 1809, the U.S. Congress passed a law requiring bids for government contracts. This meant the government had to publicly announce what it wanted to buy, and anyone could offer to do the work. Verbal contracts, or "gentleman's agreements," were a way to get around this law.

The BNC's rule was partly an attempt to follow this law and stop naval officers from using enslaved labor. One common method was to list enslaved workers as sailors on the shipyard's employment rolls. These lists were for ships being repaired or held in reserve. African Americans like Charles Ball and Michael Shiner were among the many enslaved workers listed as "Ordinary Seamen" (O.S.) on military records.

Sometimes, this practice was clearly seen in official documents. For example, a Washington Navy Yard record from June 29, 1827, shows Lieutenant John Kelly wanted his enslaved man, Thomas Penn, listed as a sailor. This way, Kelly could collect Penn's wages. Kelly was successful. Thomas Penn is listed as "O.S." (Ordinary Seaman) number 40 in the January 1, 1829, record of the Navy Yard.

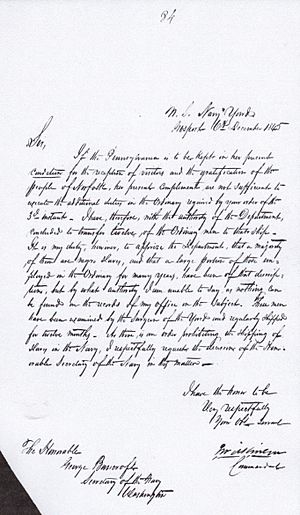

This trick was widespread. At Norfolk Navy Yard, former enslaved person George Teamoh wrote, "I was again hired by the U.S. Government to work in its ordinary service. - was there some two years [1843-1844] on board Ship USS Constitution lying in ordinary off Norfolk Navy Yard..." Teamoh even received a discharge paper in 1845. It said "George Teamoh Ordinary Seaman" was "regularly discharged from the United States Ship Constitution in Ordinary at Navy Yard Norfolk." Teamoh knew this was not true freedom. He said this part of the U.S. service was "but little different from letting out to a building contractor." Enslaved workers at Norfolk Navy Yard were often called "Landsmen" and "Ordinary Seamen" on payrolls. On December 6, 1845, Commodore Jesse Wilkinson confirmed to the Secretary of the Navy that this was a long-standing practice. Wilkinson wrote that "a majority of them [blacks] are negro slaves." He added that many enslaved people had been employed in this way for years.

In another example, two enslaved women were listed on the 1830 records of the naval shipyard as "OS 2c" (Ordinary Seamen 2nd class). Commodore James Barron signed for their wages.

Discipline and Control

Punishment for enslaved people on federal military bases varied greatly and was not consistent. Legally, enslaved workers were still the property of their owners. Owners usually handled discipline themselves. However, when enslaved people were hired by the military, owners generally gave military officers and senior civilians a lot of power. Punishments ranged from verbal warnings and threats to inform the owner, to physical beatings. These physical punishments included hits with a "boatswains starter" (a piece of rope) or whippings with a "cat-o'-nine-tails" (a multi-tailed whip designed to cause intense pain). The most severe punishment was removal from the Yard's work lists. Records of these actions against enslaved people are rarely officially reported.

At Norfolk Navy Yard, George Teamoh described that whipping and even a murder were part of the system. He recalled being whipped "unmercifully for the merest fault, such as being late at work." Teamoh said the Navy Yard "was but little different from letting out to a building contractor, varying only in point of punishment - whipping post and cow hide - gang-way and cat-o.nine tails."

Despite such hardships, Charles Ball, Michael Shiner, and thousands of other enslaved people working on federal military bases knew there were worse things. Enslaved people knew that an unhappy owner could simply "sell them South." This meant their families, friendships, and hopes would be broken apart. They would be sent to a life of harsh plantation labor. Teamoh, remembering his years at Norfolk Navy Yard, confirmed, "I was, occasionally at work in the Navy Yard, and with the hundreds of others in my condition felt to remain there rather than being worst situated, or sold."

Over time, the Navy Department became more concerned with security. Keeping track of enslaved "servants" became a regular duty of the Washington Navy Yard guard force. During this period, "servant" was a common polite word for enslaved labor in official letters. The continued use of Black people, both free and enslaved, as drivers of private carriages and as servants in officers' homes remained a concern into the 1850s. Navy Yard rules show how closely these individuals were watched. For example, "Officers Servants are to be passed in and out by the Watchman at the Flagstaff." They needed a permit from their owner.

At the Washington Navy Yard, daily records show that watch officers were sometimes told to keep an eye on a specific enslaved person's movements. For example, an entry from May 18, 1828, says, "Teppit has not made his appearance." This was likely for Thomas Teppit, an enslaved man listed as an Ordinary Seaman. He probably overstayed his pass or ran away. There are similar entries for Michael Shiner. On December 27, 1828, the officer recorded, "Michl Shiner who had liberty out from Wednesday in till Friday morning has not came in yet." The next day, Shiner returned. How common this daily watching was is hard to know. But the rules suggest that monitoring "servants'" activities became a regular part of gate guard duty.

Resistance and the End of Slavery

On January 23, 1830, white workers at Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard complained to the Navy Department. They were upset that the shipyard used enslaved people as stonemasons. They said, "On application severally by us for employment we were refused, in consequence of the subordinate officers hiring negros by the year…" Similar complaints continued until the Civil War. In 1839, William Mc Nally, a former Navy gunner, wrote a book exposing problems in the naval service. Among his claims was that naval officers allowed and profited from enslaved people working on naval ships and in navy yards. He said this happened "to the exclusion of white people and free persons of color."

Another writer noted that the use of enslaved people at naval yards was a big complaint. But he felt it was useless to fight it. In response to such criticism, starting in 1839, the Navy began to limit the number of Black sailors to five percent. They also stressed that enslaved people should never be hired. The federal government, though unwillingly, began to distance itself from using enslaved people on public projects. Congressional oversight grew. In 1842, Congress "compelled government agencies to report the number of slaves they were hiring."

The Secretary of the Navy, Abel P. Upshur, replied to a question from the Speaker of the House. He stated, "There are no slaves in the Navy, except only a few cases in which officers have been permitted to take their personal servants." He also said there was a rule against hiring enslaved people in the general service. However, Upshur carefully noted that rules did not stop them from being hired as skilled workers, laborers, or servants where needed. One scholar who reviewed Upshur's 1842 statement and the Pensacola Navy Yard records for the same time said, "For whatever reason, Upshur provides Congress with patently false information about the navy's use of slave labor in his 1842 report."

The 1820s through the 1850s saw growing opposition to slavery from African Americans. The stories of two former Washington Navy Yard employees, Charles Ball and Thomas Smallwood, give clear accounts of being enslaved and resisting in the nation's capital. Charles Ball worked at the Navy Yard for two years as a cook. After several escapes and recaptures, he gained his freedom. In 1837, he wrote his autobiography. In his story, Ball remembered life as an enslaved person as "one long waste, barren desert, of cheerless, hopeless, lifeless slavery; to be varied only by the pangs of hunger, and the stings of the lash."

Thomas Smallwood, who wrote Narrative of Thomas Smallwood, Colored Man, grew up in Washington, D.C. He worked at the Navy Yard in the 1840s. During this time, Smallwood secretly worked for the Underground Railroad. He claimed to have helped as many as 150 enslaved people escape to freedom. In his story, Smallwood declared that justice has "a black side as well as a white side." He argued that if it was fair for slaveholders to force people to work without pay because they were Black, then it was equally fair to take that labor from their masters without pay. In 1848, two Washington Navy Yard blacksmiths, Daniel Bell and Anthony Blow, helped plan one of the largest and most daring mass escapes of that time. Their plan involved 77 enslaved people and a brave 225-mile journey to freedom. This dramatic escape failed. But the sheer size and boldness of the effort greatly alarmed slaveholders and the federal government.

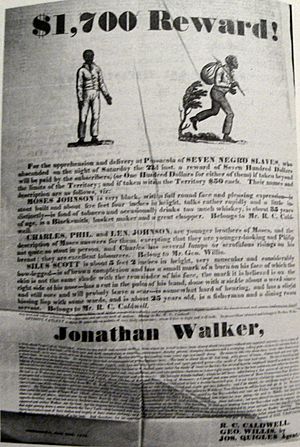

Historian Peter H. Wood emphasized that "No single act of self – assertion was more significant among slaves or more disconcerting among [southern] whites than that of running away." Enslaved people were valuable "property." Slaveholders often went to great lengths to get runaways back. They offered rewards for their capture and return. Runaways with valuable skills, like blacksmiths, were especially valuable. So, slaveholders were often desperate to get them back. One such runaway was David "Davy" Davis. Davis repeatedly tried to escape slavery and even tried to win his freedom in court. As a blacksmith's helper at the Washington Navy Yard, Davis worked six days a week, 12 hours a day. Davis and Jim, another blacksmith, sought freedom and escaped on June 14, 1809. A reward notice was published on June 16, 1809, offering $100 for Davis and Jim.

James Cassin called the two men "old runaways," meaning they had tried to escape before. He also said they "will try to pass for freeman," suggesting they might have fake freedom papers or could read and write. By June 17, 1809, Davis was caught and held in the District of Columbia Jail. Somehow, Davis got a lawyer to file a petition for him. It said he was illegally held as an enslaved person. It also said James Cassin wanted to take him from the District to New Orleans to sell him.

Davis's lawsuit failed. Cassin got him back and rented him to the Navy Yard again. The July 1811 Navy Yard payroll shows David Davis was working there again that month. He worked for 18.25 days at 85 cents a day. The same document shows James Cassin, the slaveholder, signed for and collected Davis's monthly pay of $15.54.

Davis was determined to escape slavery and make a life for himself. In 1812, he made another attempt to flee to freedom, and this time it seems he succeeded.

Thirty Dollars Reward,

Ranaway from the Navy Yard on Monday the 26th of May, a Negro man the property of the subscriber, known by the name of DAVID DAVIS; he has been working for the last three years as a helper in the blacksmith's shop; he is about 25 years of age, and 5 feet 10 to 5 feet 11 inches height; some time ago he had his left arm broke a, and lost his fore finger. I will give $ 20 for the apprehending him if taken in the district, or 30 if out of it and lodging him in jail. He was bought of Ed. H. Calvert in Prince George's county, where he has some friends, and it is probable he will stay about there; he has been in Baltimore jail where I bought him out. All persons are forbid harboring him under a penalty.

J. Cassin

P.S. Should he voluntarily return to his master, he promises to forgive him.

Georgetown, June 2 –

Cassin's plea, "Should he voluntarily return to his master he promises to forgive him," was a common request in reward notices. Desperate owners hoped to trick a runaway enslaved person into coming back willingly.

While public outcry and Black resistance greatly reduced the use of enslaved labor at the Washington Navy Yard, this was not true for the Norfolk and Pensacola Navy Yards. There, enslaved labor had more support in the white community and caused less trouble. This was also true for U.S. Army bases like Fort Jefferson and Fort Zachary Taylor. The Corps of Engineers continued to use enslaved labor almost until the Emancipation Proclamation. Former Norfolk Navy Yard enslaved person, George Teamoh, knew firsthand that "slavery was so interwoven at that time in the very ligaments of government that to assail it from any quarter was not only a herculean task."

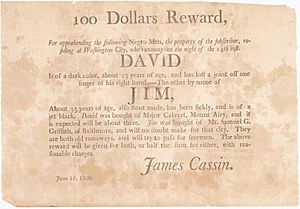

Despite Secretary Upshur's claims, there were still enslaved people in the Navy. In the summer of 1844, seven enslaved people from Pensacola Navy Yard, helped by Jonathan Walker, a white shipwright, made a brave but failed attempt to gain their freedom. Walker's imprisonment and trial brought more public attention and made national news. The seven enslaved people were severely beaten and returned to their owners. Walker spent months in jail and was later branded on his hand with the letters "S S" for "slave stealer." In April 1848, Washington Navy Yard blacksmiths Daniel Bell and Anthony Blow helped plan one of the largest and most daring slave escapes of the era. Their plan involved 77 fugitives and a daring 225-mile journey to freedom. This dramatic escape failed. But the sheer scale and boldness of the effort greatly alarmed slaveholders and the federal government.

The Civil War finally forced an end to slavery. In Washington D.C., most naval officers and some white employees went south. But Black employees remained strong supporters of the Union cause. In 1861, Michael Shiner, who had been enslaved at the Washington Navy Yard for over a decade, wrote in his diary about his excitement for the Union. He said, "On the first Day of June 1861 on Saturday Justice Clark was sent Down to the Washington navy yard For to administer the oath of allegiance to the mechanics and the Laboring Class of working men Without Distinction of Color for them to Stand by the Stars and Stripes and defend for the union and Captain Dahlgren Present and I believe at that time I Michael Shiner was the first Colored man that had taken the oath in Washington DC and that oath Still Remains in my heart."

In short, the use of enslaved labor on navy yards and army bases grew from local practices. These mirrored those in the surrounding communities. They were also like the practices first used by the new federal government to build the U.S. Capitol and the White House. The hiring of white, free Black, and enslaved labor at the same time had long roots, going back to the colonial era in Norfolk. Renting enslaved people by the army and navy expanded slavery, especially in Florida. There, building and maintaining military bases was the main reason for slavery's growth. It provided a ready market for slaveholders to rent their enslaved people. Opposition to enslaved labor on military bases was always scattered. But it gained more strength with each decade. Black resistance and white fear of a growing free Black population led to calls for Congress to oversee and accurately count enslaved people on military bases.

The District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act, signed on April 16, 1862, ended slavery forever in the nation's capital. In his diary entry for that day, Michael Shiner wrote a short account of the Act. He ended with the words: "Thanks Be to the Almighty." The final end of slavery was signaled on January 1, 1863. President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation into law. While the Civil War continued for two more bloody years, there was no turning back. Shiner carefully copied the proclamation into his diary. Later, thinking about his freedom, he strongly stated, "The only master I have now is the Constitution."

|

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |