Southern Ndebele people facts for kids

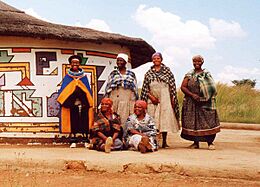

The women of Loopspruit Cultural Village, near Bronkhorstspruit, in front of a traditionally-painted Ndebele dwelling.

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2.1 million (2023 Census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| IsiNdebele, English, Afrikaans |

|

| Religion | |

| Christian, Animist | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Nguni peoples (especially Northern Ndebele) |

| Ndebele | |

|---|---|

| Person | iNdebele |

| People | AmaNdebele |

| Language | IsiNdebele |

| Country | KwaNdebele |

The Southern Ndebele people, also known as AmaNdebele, are a group of Bantu people living in Southern Africa. They speak the Southern Ndebele language (isiNdebele).

This group is different from the Northern Ndebele. The Northern Ndebele separated from the Zulu a long time ago. Southern Ndebele people mostly live in the provinces of Mpumalanga, Gauteng, and Limpopo. These areas are in the northeast of South Africa.

Contents

History of the Ndebele People

Early Beginnings and Migrations

The Ndebele people's story starts with the Bantu Migrations. These were big movements of people from the Great Lakes region of East Africa. Bantu-speaking groups moved south across the Limpopo River into what is now South Africa. Over time, they mixed with and took over from the original San people in the northeast.

Around 1450, when the Kingdom of Zimbabwe ended, two main groups lived south of the Limpopo River. These were the Nguni on the eastern coast and the Sotho–Tswana on the central plateau. Between the 1400s and early 1800s, these groups split into smaller, unique cultures. The Ndebele were one of these new groups.

Moving South and North

The first known Ndebele chief lived with his people near the Drakensberg Mountains. Their main town was called eLundini. This Chief Ndebele broke away from a larger group and formed his own nation.

Later, Jonono, a great-grandson of Chief Ndebele, moved his people north. They settled near modern-day Ladysmith. Jononoskop is believed to be Jonono's burial place.

Nanasi, Jonono's son, became the next King (INgwenyama). Stories say Nanasi was immune to poisons. He even ate poisonous fruit and was unharmed! This place is now called "Butiswini," meaning 'a poisoned stomach.'

Journey Across the Vaal River

Nanasi died without children, so his brother Mafana became King in the mid-1500s. Mafana led his people northwest, crossing the Drakensberg Mountains. He tried to cross the Vaal River but sadly drowned.

After Mafana's death, his son Mhlanga became King. Mhlanga successfully led his people across the Vaal River. They settled near modern-day Randfontein. Mhlanga built a new capital called eMhlangeni, which means 'Mhlanga's place.'

Mhlanga's son, Musi, became the next King. The area around eMhlangeni became dangerous due to conflicts with Sotho-Tswana tribes. Musi moved the Ndebele north again. They crossed the Jukskei River and Hennops River. They settled along the Apies River, north of Wonderboomkop. Musi built two towns: KwaMnyamana, the new capital, and eMaruleni, named for its many Marula trees.

At KwaMnyamana, Musi's Ndebele people thrived. They traded with the BaKwena and BaKgatla tribes. They also met the nomadic San people, whom they called "AbaTshwa."

The Manala-Ndzundza Conflict

King Musi had many children from different wives. Manala was the first son of his 'Great Wife,' making him the rightful heir. However, Ndzundza, the first son of Musi's second wife, was born earlier.

Ndebele tradition says the first son of the 'Great Wife' becomes ruler. When Musi was old and blind, his second wife tricked him. She presented her son Ndzundza as Manala. She asked Musi to give Ndzundza the "iNamrhali," a special gift (magical beads or staff) passed to new rulers.

Ndzundza got the iNamrhali but ignored his father's warning to stay at KwaMnyamana. He fled east with many followers. Manala returned to find his father dead and Ndzundza gone with the iNamrhali. Manala declared Ndzundza had stolen his birthright and vowed to bring him back.

Manala chased Ndzundza, fighting two battles at the Elands River and Wilge River. Ndzundza won both. Manala retreated to gather more forces. They met for a third battle at the Olifants River.

During this battle, an old woman named Noqoli stepped in. She stopped the brothers from fighting and called a meeting for peace. They agreed there would be two Ndebele kings. Ndzundza would rule his own kingdom with the iNamrhali. Manala would remain the senior king at KwaMnyamana. The Olifants River would be the border between their lands. This agreement was called "isiVumelano sakoNoQoli." They also agreed never to fight again.

This story is similar to the biblical story of Jacob and Esau, where Jacob tricks his blind father Isaac to get Esau's blessing.

Over the years, there was debate about who was the senior king. In 2010, a commission declared Mabhena (Manala line) the senior king. However, the President of South Africa later overturned this. In 2017, the High Court confirmed Makhosonke II (Manala line) as the senior king of the Ndebele people in South Africa.

After the Ndebele Split

After the Manala-Ndzundza conflict, Musi's other sons went their separate ways. Some joined Ndzundza, while others moved north or even returned to older Ndebele lands. Many of these smaller groups eventually blended into the larger Sotho-Tswana groups around them. However, the Manala and Ndzundza descendants kept their distinct culture and language.

Manala returned to KwaMnyamana and buried Musi under the famous Wonderboom tree. Manala's rule brought good times to his people. His descendants continued to expand their territory, controlling much of northern Gauteng.

Ndzundza and his followers moved to the source of the Steelpoort River. They built their first capital, KwaSimkulu, near modern-day Belfast. Their new territory stretched from the Olifants River to the Elands River.

Later, King Bongwe moved the Ndzundza capital to KwaMaza to better defend against raids from the Nguni and Sotho-Tswana peoples. Many kings followed, fighting to protect and expand their lands.

Mzilikazi and The Mfecane Era

In the early 1820s, a large Khumalo army led by Mzilikazi arrived north of the Vaal. Sibindi, the Manala king, tried to make peace by offering his daughter to Mzilikazi. But Mzilikazi's men attacked Sibindi's warriors.

Sibindi called for all Ndebele to unite against Mzilikazi. However, Magodongo of the Ndzundza had limited forces due to his own war. Sibindi fought Mzilikazi's army near Pretoria but was eventually killed. The Manala capital, KwaMnyamana, was destroyed.

Mzilikazi's forces continued their conquest. By 1826, they attacked Magodongo's capital, KwaMaza. Magodongo retreated to a new capital, eSikhunjini, but it was also attacked. Magodongo and his sons were captured and killed.

By December 1826, Mzilikazi had defeated both the Manala and Ndzundza Ndebele. He established his own capital, "Kungwini," near Wonderboompoort. Mzilikazi ruled this area for over 10 years, sending raiding parties far and wide.

Mzilikazi's rule ended when the Voortrekkers arrived in 1836. After two years of fighting, Mzilikazi and his people were forced out of Transvaal and across the Limpopo River. They eventually settled in what is now Matabeleland in Zimbabwe in 1840.

The Transvaal Republic Era

After Mzilikazi's defeat, the lands between the Vaal and Limpopo rivers were left in chaos. Some Voortrekkers (Dutch-speaking settlers) claimed these lands, believing they were empty. This led to conflicts with African groups like the Ndebele who were trying to reclaim their homes.

The Manala Ndebele were hit hardest by Mzilikazi's occupation. Their kings were killed one after another. Silamba, a son of Mdibane, became king in 1832. He rebuilt the Manala kingdom over 60 years. However, he faced strong resistance from Voortrekker settlers and lost much land. In 1873, Silamba moved his capital to "KoMjekejeke" in Wallmansthal.

Among the Ndzundza, Mabhoko became king in 1840. He was young, smart, and brave. Mabhoko moved the Ndzundza capital to a heavily fortified place called "eMrholeni," near caves called "KoNomtjarhelo." He made an alliance with the BaPedi chief Malewa to protect his northern border.

As more settlers arrived, Mabhoko moved his capital into the caves of KoNomtjarhelo, making it a strong fortress. Skirmishes broke out between the settlers and the Ndebele-Pedi alliance. Mabhoko's forces, armed with firearms, won many early battles.

In 1847, the Ndzundza won a big battle against the Boers. Many Boers left the area, and those who stayed had to recognize Mabhoko's authority and pay taxes.

Tensions grew worse with the Sand River Convention in 1852. This treaty between the British and Boers recognized Boer independence north of the Vaal River. However, it ignored the African people already living there. This meant the Boers claimed land that was already occupied by African kingdoms.

In 1861, Sekhukhune became king of the Marota Empire, expanding its lands. This caused tension with Mabhoko, who eventually submitted to Sekhukhune's rule.

In 1863, the Boers attacked KoNomtjarhelo with the help of Swazi forces, but they failed. A second attack in 1864 also failed. Despite Mabhoko's victories, the Ndebele territory kept shrinking. Mabhoko died in 1865, and his son Mkhephuli became king. Nyabela became king in 1879.

The Mapoch War (1882–83)

In 1876, the Transvaal Republic lost a war against Sekhukhune. The British then took over the Transvaal in 1877. This led to the First Anglo-Boer War (1880–81), which the Boers won.

By Nyabela's rule, the Ndzundza kingdom was about 84 square kilometers with 15,000 people. After the Transvaal regained independence in 1881, relations with the Ndebele worsened. Nyabela refused to pay taxes or allow a census. The main reason for war was Nyabela sheltering Mampuru, who had killed his brother Sekhukhune.

On October 12, 1882, General Piet Joubert was ordered to raise an army. His goal was to capture Mampuru and punish anyone who helped him. By the end of October, about 2,000 Boer soldiers arrived in Ndzundza territory.

General Joubert sent Nyabela an ultimatum: surrender Mampuru and cooperate, or face war. Nyabela famously replied that he had "swallowed Mampuru," meaning they would have to kill him to get Mampuru.

The Ndebele fortress of KoNomtjarhelo was very strong. It was located on cliffs with many caves and tunnels. These caves offered refuge and storage for a long siege. The Boers decided not to attack directly but to starve the Ndebele out.

On November 7, the first clash happened. Ndebele raiders tried to steal Boer oxen but were stopped. The Boers used cannons and dynamite, but the Ndebele hid in their deep caves. The Boers were reinforced by other African tribes who wanted revenge on Mampuru.

In January, the Boers captured KwaMrhali (Boskop). On February 5, they launched a big attack on KwaPondo, which fell after fierce fighting. Now only KoNomtjarhelo remained. The Boers began digging a trench to tunnel under the mountain and use dynamite.

The Ndebele were running out of food. By early April, most chiefs surrendered, but Nyabela chose to fight on. The Ndebele continued to resist, even launching a successful raid for oxen in June.

On July 8, Nyabela finally handed over Mampuru, hoping to end the siege. But it was too late. The war had cost the Transvaal Republic a lot of money and lives. General Joubert demanded unconditional surrender. Two days later, Nyabela surrendered with 8,000 warriors. The Ndebele land was taken as punishment.

Nyabela and Mampuru were sentenced to death. Mampuru was executed. Nyabela's sentence was changed to life in prison. He was released after 15 years and died in 1902.

The Ndebele social and political structures were abolished. Their land was divided among white soldiers. Ndebele people were forced to work for white farmers as laborers for five-year periods.

KwaNdebele Bantustan

In 1970, the Apartheid government passed a law called the Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act. This law forced black South Africans to become citizens of their traditional "homelands" or Bantustans. This led to the creation of the KwaNdebele 'Homeland' in 1977.

Most Ndebele in this homeland were Ndzundza. There were attempts to get more Manala people to move there. Tensions rose in the 1980s when the idea of KwaNdebele becoming independent came up. Some politicians wanted to make the smaller Manala group the supreme rulers, claiming the land originally belonged to them.

In 1977, three tribal authorities joined KwaNdebele. They formed the Mnyamana Regional Authority. The Ndzundza Regional Authority formed the South Ndebele Territorial Authority.

A legislative assembly was created in 1979. This caused a shift in power from traditional leaders to appointed officials. By 1985, some traditional chiefs felt ignored by the government. In 1994, the African National Congress won the election. The Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act was removed. KwaNdebele and its people became part of the Republic of South Africa again.

Ndebele Culture and Art

Social Structures

The leader of a Ndebele tribe was called the iKosi (tribal head). He was helped by a family council. Smaller areas were managed by ward heads, and families by family heads. A family's home was called an umuzi. It usually included the family head, his wife, and unmarried children. If a man had more than one wife, the umuzi was divided for each wife.

Sometimes, an umuzi grew to include married sons and younger brothers. Each tribe had several patrilineal clans, meaning members shared the same male ancestor.

Personal Adornment

Ndebele women traditionally wore many ornaments. These showed their status in society. After marriage, their clothing became more detailed. In the past, married Ndebele women wore copper and brass rings (idzila) on their arms, legs, and neck. These rings showed their bond to their husband. They would only remove them after his death. Husbands gave their wives rings; richer husbands meant more rings. Today, wearing these rings permanently is less common.

Married women also wore neck hoops made of grass and beads (isirholwani) for special events. Newly married women or girls ready for marriage might wear them too. Married women wore a five-fingered apron (itjhorholo) after their first child was born. The marriage blanket (untsurhwana) was decorated with beads to show important life events. For example, long beaded strips meant her son was undergoing initiation, showing her higher status. Married women always covered their heads to show respect for their husbands. Boys wore small goatskin aprons or nothing. Girls wore beaded aprons or skirts from a young age. Ndebele men wore ornaments made by their wives for ceremonies.

Artistic Expressions

Ndebele House Painting

Traditional Painting Style

Ndebele art, especially house painting, is a key part of their identity. It's not just beautiful; it tells a story about their culture. Ndebele artists are skilled at mixing new ideas with old designs. They often show straight lines and shapes from their surroundings.

Women painted the colorful and detailed patterns on their houses freehand. They planned the designs but didn't draw them first. The perfect symmetry and straight lines were done without rulers! This painting allowed women to express themselves. Sometimes, they even made sculptures.

The back and side walls were often painted in earth colors. They had simple geometric shapes made with fingers and outlined in black. Traditionally, they used natural colors from ground ochre and clays. These included white, browns, pinks, and yellows. Because these natural paints were delicate, women repainted the walls every season.

The most creative designs were on the front walls of the house. The wall enclosing the courtyard, called the gateway (izimpunjwana), received special attention. Windows were often a focus for designs, and their patterns weren't always symmetrical. Sometimes, fake windows were painted to add interest. In the early 2000s, King Mayitjha III started painting lessons for young women. This was to keep Ndebele art, both beaded and painted, alive.

Modern House Painting

Today, Ndebele artists use more colors like blues, reds, greens, and yellows. This is because these paints are easy to buy. As Ndebele society changed, their art also changed. Women who worked in cities would paint images to show their hopes for a better life.

Modern paintings might include cars, clocks, airplanes, and running water. Artists also add realistic shapes to their traditional geometric designs. Many Ndebele artists now paint inside houses too.

Beadwork

The beadwork made by Ndebele women can show a person's age or marital status. It can also show if they've had children or gone through special rituals. Before the 1920s, white beads were most common. After that, colorful beads became available, and designs started to show daily life and geometric shapes.

Making beadwork used to be a social activity for women after their chores. Today, many items are made to sell to tourists. This shift began in the 1960s when collectors started buying Ndebele beadwork. Selling beadwork helped families earn money, especially during the apartheid era when trade was difficult.

Types of Ndebele Beadwork

- Iinrholwani: These are colorful hoops for the neck, arms, hips, and legs. They are made by winding grass into a hoop, covering it with cotton, and decorating it with beads. They are boiled in sugar water to make them strong. Initiated girls and married women wear them as beautiful decorations.

- Isithimba: This is a back skirt worn by unmarried women. It's made from goatskin and decorated with beads. It has brass rings (nkosi) that show status.

- Nyoga (snake): This is a long beaded train made of white beads. The bride wears it at the first wedding ceremony. Female relatives weave it. Its patterns and length can show if the bride is the groom's first wife or if she is a virgin.

- Iinga koba ("the long tears"): Mothers wear these when their son is away for male initiation. They show the sadness of their son growing up but also the joy of him becoming a man.

- Isiphephetu: These are stiff beaded aprons worn by girls going through initiation. They show that the girl is becoming a woman.

Special Occasions

Courtship and Marriage

Ndebele people only married members of different clans. However, a man could marry a woman from his paternal grandmother's family. Before the wedding, the bride stayed hidden for two weeks in her parents' house.

When she came out, she was wrapped in a blanket and held an umbrella. A younger girl (Ipelesi) helped her. On her wedding day, the bride received a marriage blanket. Over time, she would decorate it with beadwork. There's a Ndebele saying, "a woman without a blanket is not a woman." Married women wear a blanket to show modesty and respect. After marriage, the couple lived with the husband's clan. Women kept their father's clan name, but children took their father's clan name.

Ama-Ndebele-Kingdom Rulers

Legendary Rulers

| Name | Notes |

|---|---|

| King Ndebele | Son of King Mabhudu. He was a Chief in the lands of the Bhaca and Hlubi. |

| King Mntungwe | Son of King Ndebele. |

| King Mkhalangwana | Son of King Mntungwe. |

| King Jonono | Son of King Mkhalangwana. He moved his people to the area northeast of modern-day Ladysmith. |

| King Nanasi | Son of King Jonono. Stories say he could eat poisonous fruit without harm. |

Semi-historical Rulers

| Name | Notes |

|---|---|

| King Mafana | Lived in the mid-1500s. Son of King Nanasi. He moved his people from Ladysmith and drowned while trying to cross the Vaal River. |

| King Mhlanga | Son of King Mafana. He led his people northwest and settled near modern-day Randfontein, calling the area eMlhangeni. |

| King Musi | Son of King Mhlanga. He moved his people north of the Magaliesberg Mountains. They settled near the Apies River, establishing KwaMnyamana (capital) and eMaruleni. His people thrived here. |

The Ndebele People Split

After King Musi, his sons Prince Manala and Prince Ndzundza fought over who would rule. They had three big battles. The first was at MaSongololo, the second at Wilge River, and the last at Olifants River. In the end, both sons got a kingdom to rule within the larger Ndebele kingdom.

For a long time, it was unclear who was the senior king. In 2004, the Nhlapo Commission decided that Prince Manala's line was the senior house of the Ndebele kingdom in South Africa.

| Names | Notes |

|---|---|

| King Manala | Son of King Musi. After battling his brother Ndzundza, he returned to KwaMnyamana and expanded the Manala territory. |

| King Ntsele | Son of King Manala. |

| Magutshona | Son of King Ntsele. |

| King Ncagu | Son of King Magutshona. |

| Prince Mrawu ‡ | Son of King Magutshona. He ruled as a regent until his nephew Prince Mbuyambo was old enough. |

| King Mbuyambo | Son of King Ncagu. |

| Mabhena I | Son of Buyambo. He expanded Manala territory from the Hennops River south to Marblehall north. |

| Mdibane | Son of Mabhena I. He inherited his father's lands, including the capital KwaMnyamana. |

| Name | Notes |

|---|---|

| Ndzundza | Through war with his brother Manala, he established his own kingdom. He claimed lands from the Olifants River to the Elands River. He built his capital, "KwaSimkulu," near Belfast. |

| Mrhetjha | Son of Ndzundza. |

| Magobholi | Son of Mrhetjha. |

| Bongwe | Son of Magobholi. He moved the Ndzundza capital to "KwaMaza" to better defend against raids from the Swazi and BaPedi. He died without children. |

| Sindeni | Son of Mrhetjha and brother to Bongwe's father. |

| Mahlangu | Grandson of Sindeni. He tried to expand Ndzundza territory but had limited success. He was known as a skilled military leader. |

| Phaswana | Son of Mahlangu. He was killed in war. |

| Maridili | Son of Mahlangu. He won battles against the BaPedi. He died without children. |

| Mdalanyana | Son of Mahlangu. He was killed in war. |

| Mgwezana | Son of Mahlangu. He was also killed in battle. |

| Dzela ‡ | Son of Mahlangu. He served as a regent. He was killed in a war to claim more territory. |

| Mrhabuli Srudla | Son of Mahlangu. After many wars, the mystical iNamrhali was lost forever. |

Historical Rulers

| Name | Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sibindi | 1817–1826 | Son of Mdibane. He was killed by Mzilikazi Khumalo's forces. |

| Mvula | 1826–1827 | Son of Mdibane. He was also killed by Mzilikazi Khumalo's forces. |

| Mgibe | 1827–1832 | Son of Mdibane. He was killed by Mzilikazi Khumalo's forces. |

| Silamba | 1832–1892 | Son of Mdibane. He rebuilt the Manala kingdom after Mzilikazi Khumalo's occupation. He ruled for 60 years. |

| Mdedlangeni | 1892–1896 | Son of Salimba. He tried to resist the expansion of The Transvaal Republic. He died under mysterious circumstances. |

| Libangeni ‡ | 1896–unknown | Son of Salimba. He lived in exile and served as regent for Mbedlengani's son. |

| Mabhena II | unknown–1906 | Son of Mbedlangeni. He returned from exile and died in 1906. |

| Mbhongo I | 1906–1933 | Son of Mabhena II. |

| Mbulawa | 1933–1941 | Son of Mbhongo I. |

| Makhosoke I | 1941–1960 | Son of Mbulawa. |

| Mbongo II | 1960–1986 | Son of Makhosoke I. |

| Enoch Mabhena

(as Makhosoke II) |

1986–present | Son of Mbongo II and the current King of The Manala Ndebele. |

| Name | Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Magodongo | 1811–1827 | Son of Mgwezana. He moved the Ndzundza capital to eSikhunjini. He was killed by Mzilikazi Khumalo's forces. |

| Sibhoko ‡ | 1827–1835 | Son of Magodongo. He served as regent. He was killed after a dispute with a Sotho-Tswana Chief. |

| SoMdeyi ‡ | 1835–1840 | Son of Magodongo. He served as regent and was killed by Mzilikazi Khumalo's raiding party. |

| Mabhoko I | 1840–1865 | Son of Magodongo. He moved the Ndzundza capital to eMrholeni, near the KoNomtjarhelo caves. He had many conflicts with The Transvaal Republic. |

| Mkhephuli | 1865–1873 | Son of Mabhoko I. Also known as Soqaleni or Cornelis. |

| Rhobongo ‡ | 1873–1879 | Son of Mabhoko I. He served as regent for Fene. |

| Nyabela ‡ | 1879–1902 | Son of Mabhoko I. He served as regent for Fene. He lost a war to The Transvaal Republic. |

| Fene | 1902–1921 | Son of Mkhephuli. He bought land near Pretoria and established modern-day KwaMhlanga. |

| Mayitjha | 1921–1961 | Son of Fene. |

| Mabusa Mabhoko II | 1961–1992 | Son of Mayitjha. |

| Nyumbabo Mayitjha II | 1992–2005 | Son of Mabusa Mabhoko II. |

| Sililo ‡ | 2005-2006 | Son of Mhlahlwa. He served as regent for Mabhoko III. |

| Mbusi Mahlangu

(as Mabhoko III) |

2006–present | Son of Nyumbabo Mayitjha II. He has challenged the seniority of the Manala king. |

(‡ = Ruled as regent.)

Famous Southern Ndebele People

See also

- List of Xhosa people

- List of South Africans

- List of Southern Ndebele people

- List of Zulu people

- List of South African office-holders

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |