Spanish crisis of 1917 facts for kids

The Crisis of 1917 is the name historians use for big problems that happened in Spain during the summer of 1917. Three main challenges threatened the Spanish government and its political system, known as the Restoration:

- A military movement called the Juntas de Defensa.

- A political movement, the Parliamentary Assembly, started in Barcelona.

- A social movement, a general strike by workers.

These events happened at the same time as important things were changing around the world. However, outside of Spain, this period is not usually called a "crisis." The term is often used for problems related to World War I, like the Conscription Crisis of 1917 in Canada. Spain stayed neutral during the entire war.

Contents

What Was Happening in the World?

In Russia, the February Revolution of 1917 removed the Tsar (the king). The new government tried to create a democracy while still fighting in World War I. This was very hard for Russia. Later that year, the Bolsheviks took power in the October Revolution.

World War I was also changing. Germany was doing well on the eastern front. But then the United States joined the war on April 6, 1917. This made the western front much more difficult for Germany.

Even though its effects were not fully clear in 1917, the Spanish flu began to spread in late 1917. It became the deadliest sickness in modern history. It was called "Spanish Flu" because Spanish newspapers were the first to report on it. This was because Spain was neutral in the war, so its news was not censored. The flu killed between 50 and 100 million people. This was far more than the deaths from World War I. The war also helped the flu spread quickly around the world. In Spain, about 8 million people got sick, and around 300,000 died.

The Crisis in Spain

Money and Society

Spain's neutrality in World War I meant it could sell many things to other countries. This included farm products, minerals, and manufactured goods. Factories in Catalonia (textiles) and the Basque Country (iron) did very well. Spain's trade balance went from losing money to gaining a lot of money.

This economic boom helped rich factory owners, business people, and landowners. However, it also caused inflation, meaning prices went up a lot. But salaries (wages) did not increase much. So, while the rich got richer, most people's lives became harder. This was especially true for factory workers in cities.

In the countryside, the situation was different. Inflation still hurt, but small farmers could grow their own food. However, farm workers who owned no land suffered greatly. This was common in southern Spain, like Andalusia and Extremadura. By 1917, the crisis meant that wealth was being shared very unevenly. Many people moved from farms to cities, making tensions worse between city and country areas.

Three Big Challenges

Military Challenge: The Juntas de Defensa

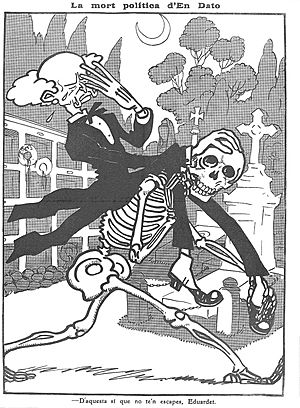

The Defence Juntas were groups of military officers who formed a kind of union. They did this without the government's permission. This was a clear challenge to the government led by Manuel García Prieto. He could not control them and had to resign. The new conservative leader, Eduardo Dato, then made the Juntas legal.

The Juntas chose a name that sounded important, like groups from Spain's War for Independence. They said they wanted to protect the interests of mid-ranking officers. But they clearly wanted to get involved in politics.

The military was very focused on keeping Spain united. This was shown in 1905 when they attacked a Catalan newspaper. After this, a law was passed that allowed the military to judge "offenses against national unity" or military honor. Spanish soldiers felt stuck. Soldiers in other countries were getting promoted because of the war. But Spain was neutral, so its soldiers had no war to fight. They also had no colonies left after the Spanish–American War of 1898. Spain had too many officers for its number of soldiers. For example, Spain had 16,000 officers for 80,000 soldiers, while France had 29,000 officers for 500,000 soldiers. Also, inflation made military salaries worth less.

The Juntas started in 1916. The government wanted officers to pass tests for promotions, which the Juntas did not like. The government first accepted their complaints. But seeing the danger of a military union, it ordered the Juntas to break up. This did not work. The Juntas became more vocal, especially the one in Barcelona led by Colonel Benito Márquez.

In May 1917, the government tried to stop them. The Minister of War ordered the arrest of several Junta members, including Colonel Márquez. But other military groups, even the Civil Guard, supported the arrested officers. This made the situation very tense. García Prieto resigned. King Alfonso XIII, who was close to the military, asked Eduardo Dato to form a new government. Dato's government gave in to the military's demands. They freed the arrested officers and made the Juntas legal. To control the situation, the new government also suspended some constitutional rights and increased censorship of the press.

Political Challenge

Francesc Cambó led the Regionalist League of Catalonia, which represented the rich people of Catalonia. They had gained power locally through the Commonwealth of Catalonia, formed in 1914. When the crisis started, Cambó asked the government to call a meeting of the Parliament. The government refused.

Since they could not use normal parliamentary ways, many politicians from Catalonia (48 of them) met in the Assembly of Parliaments in Barcelona in July 1917. They demanded a new assembly to rewrite the government's structure. They also wanted more regional power and changes in the military and economy. They even tried to connect their movement to the unhappy military officers.

Even though this Assembly had less than 10% of all politicians, it created a feeling that a revolution might happen. It questioned the main ideas of the Restoration political system. This system involved two main parties taking turns governing and the king having a lot of power. Dato's government called the Assembly rebellious. They shut down newspapers and sent the military to Barcelona.

In mid-July, the Assembly met again. This time, 68 politicians attended, including republicans like Alejandro Lerroux and a socialist, Pablo Iglesias. They agreed that a new Parliament was needed to solve the country's problems. But they said this Parliament could only be called by a government that truly represented the country's will. They planned to meet again in August, but the police broke up the Assembly on July 19.

Social Challenge

Barcelona, Spain's economic center, often had social problems, like the Tragic Week of 1909. Workers and employers often fought. Employers used tactics like hiring scabs (workers who cross picket lines) and sometimes violence. Workers used peaceful methods like strikes, but also sometimes violence.

The workers' movement in other parts of Spain was less developed. But they saw a chance to use the government's weakness. The UGT, a socialist union, organized a revolutionary general strike in August 1917. The CNT, an anarchist union, supported it. The two unions had been working together since late 1916.

The agreement for a general strike was made in Madrid in March 1917. Leaders from both unions signed a statement saying: "To make the ruling classes agree to basic changes that ensure decent living conditions for the public, the workers of Spain must use a general strike, with no end date, as their strongest weapon to claim their rights."

Despite some disagreements from anarchists, the unions talked with other political parties, like the republicans. They discussed forming a temporary government.

The calls for the strike were a bit confusing. Some messages said it would be a revolution, while others said it would be peaceful. The UGT tried to stop small, local strikes. However, the long preparations for the strike worked against it. The government arrested the manifesto signers and closed socialist meeting places. These actions spread out the strikers' efforts. A railway workers' strike in Valencia on August 9, protesting the arrests, quickly spread across the country between August 10 and 13.

The strike initially stopped work in most major industrial areas, like Biscay and Barcelona. It also affected cities like Madrid and Valencia, and mining areas like Asturias. But it only lasted about a week. Small towns and rural areas were barely affected. Railway communication, which was very important, was only briefly stopped.

What Happened Next?

The three challenges from the military, Catalan politicians, and workers made people fear a revolution, like what happened in Russia. However, the army quickly followed government orders and stopped the strike within three days. Only in some mining areas, like Asturias, did the conflict last longer. Colonel Márquez himself helped put down the revolt in Sabadell. The army used violence against the strikers and ignored some rules, like arresting a politician who had special protection.

Meanwhile, the Regionalist League of Catalonia became worried about the social unrest. They decided to support a national government with the king's help. García Prieto became prime minister again. His government included Cambó and promised elections in February 1918. These elections were unusual because no party won a clear majority. This was new for Spain. Usually, the king would appoint a government, which would then arrange elections to ensure they won easily. This time, many parties had to work together to form a new national government, led by Antonio Maura. This happened again in 1919. The old way of two parties taking turns governing did not return until 1920.

In August 1917, members of the strike committee, including future socialist leaders Francisco Largo Caballero and Julián Besteiro, were arrested. They were tried and sentenced to life in prison. However, they were all elected as politicians in the elections of February 1918. It was a scandal to keep elected politicians in prison. After a big campaign, they were released. Other strike leaders were also imprisoned or fled the country. The crackdown on the strike resulted in 71 deaths, 156 injuries, and about two thousand arrests.

The repression of the strike made the king and the army even closer. It also increased their role in public life. Many people, including thinkers, workers, and middle-class citizens, became unhappy with the political system. Since the late 1800s, there had been calls for a strong leader to fix Spain's problems. This leader appeared during the next big crisis, the Battle of Annual. The army, being the strongest institution, produced this leader: General Miguel Primo de Rivera. With the king's agreement and support from the Catalan rich, he became a dictator in 1923.

|

See also

In Spanish: Crisis española de 1917 para niños

In Spanish: Crisis española de 1917 para niños