Tây Sơn wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tây Sơn WarsVietnamese Civil War of 1771–1802 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

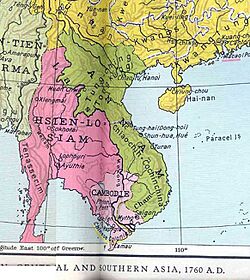

Vietnam in 1792. The green area was controlled by the Nguyễn lords; the yellow and dark areas were under Tây Sơn leaders Nguyễn Nhạc and Nguyễn Huệ. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Cham people Chinese Vietnamese (1771–1777) Pirates of the South China Coast |

Royal Vietnamese army under Lê Chiêu Thống |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

Po Tisuntiraidapuran Chen Tianbao Zheng Yi † |

Lê Chiêu Thống |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Tây Sơn: 25,000 (1774) South China sea pirates: 50,000 (1802) |

Nguyễn lord: 30,000 (1771) Trịnh lords: More than 150,000 (1786) |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1–2 million civilians | |||||||

The Tây Sơn wars, also called the Vietnamese civil war of 1771–1802, were a series of big fights in Vietnam. They started with a peasant uprising in Tây Sơn District led by three brothers: Nguyễn Nhạc, Nguyễn Huệ, and Nguyễn Lữ. The wars began in 1771 and ended in 1802. That's when Nguyễn Phúc Ánh, a descendant of the Nguyễn lords, won. He defeated the Tây Sơn and united Vietnam, renaming the country.

Contents

- Overview of the Tây Sơn Wars

- Why the Wars Started

- Vietnam Divided: The Trịnh and Nguyễn Lords

- Problems in Vietnam in the 1700s

- The Rise of the Tây Sơn Brothers

- Wars from 1773 to 1785

- Tây Sơn Takes Over the North (1785–1788)

- China Invades Northern Vietnam

- Quang Trung in Power (1789–1792)

- Tây Sơn–Nguyễn War (1792–1802)

- Aftermath of the Wars

- Legacy of the Tây Sơn Wars

Overview of the Tây Sơn Wars

The Tây Sơn rebellion was a big uprising led by the three Nguyễn brothers. It started in central Vietnam in 1771. Their forces grew and eventually took over the ruling families and the old dynasty. The Tây Sơn leaders then became the rulers of Vietnam. They held power until Nguyễn Phúc Ánh defeated them. Nguyễn Phúc Ánh was from the Nguyễn lord family, who the Tây Sơn had overthrown earlier.

Vietnam faced many problems in the late 1700s, like bad weather and economic troubles. These issues also affected other countries in Southeast Asia. The country was divided into three main regions, and it was hard to unite them. The Tây Sơn wars were long and complicated. They showed how much Vietnamese society changed during a time of big environmental problems.

Why the Wars Started

Early Problems in Royal Rule

The problems that led to the wars began much earlier, in the 15th century. A Vietnamese king named Lê Thánh Tông (who ruled from 1460 to 1497) made the country strong and rich. He brought in ideas from Confucianism, which helped the government. Vietnam's population grew a lot during his rule.

However, after his death, the royal family's power weakened. Kings like Lê Uy Mục caused instability. The ruling Lê family started to rely on two other powerful families: the Trịnh and the Nguyễn. These families began to fight for power. Bad weather, like droughts and floods, also hit Vietnam in the early 1500s. This hurt the economy. There were many peasant revolts and quick changes in rulers, which made the country unstable.

In 1527, a military officer named Mạc Đăng Dung took control. He removed the Lê king and became the ruler. The Mạc kings brought some peace, but a loyal supporter of the Lê family, Nguyễn Kim, went to Laos. He found a Lê prince and declared him the new king in 1533. This led to more fighting. China even threatened to invade Vietnam. Eventually, the Mạc family gave in to China, and Vietnam's status as an independent country was lowered for a while.

The Long Civil War (1545–1592)

The Lê family slowly regained power with help from the Nguyễn and Trịnh families. But as they fought the Mạc, a rivalry grew between the Nguyễn and Trịnh. This rivalry became stronger when the Nguyễn leader, Nguyễn Kim, was killed in 1545. The Trịnh family then became more powerful.

Nguyễn Kim's younger son, Nguyễn Hoàng, feared for his life. He asked to be made governor of the southern lands of Thuận Hoá and Quảng Nam. The Trịnh leader agreed, thinking it would get Nguyễn Hoàng out of the way. In 1558, Nguyễn Hoàng moved south. This started a political division in Vietnam that lasted over 200 years. Nguyễn Hoàng built up his power in the south. Both Nguyễn Hoàng and the Trịnh still worked together to bring the Lê monarch back to the capital, Hanoi. In 1592, they took back the northern delta from the Mạc. This civil war caused many deaths, with over 440,000 people dying.

Vietnam Divided: The Trịnh and Nguyễn Lords

For the next two centuries, Vietnam was split into two parts. The Trịnh lords ruled the North, called Đàng Ngoài (Tonkin). The Nguyễn lords ruled the South, with Huế as their capital, called Đàng Trong (Cochinchina). The Lê emperor was still the official ruler, but he was controlled by the Trịnh lords.

Vietnam had a short period of peace. Catholicism became more popular as Jesuit missionaries arrived. Trade also grew, especially in silk. In 1624, the Nguyễn leader refused to pay taxes to the Trịnh. This led to the Trịnh–Nguyễn War, which lasted for almost 45 years (1627–1672). The war ended in a stalemate, and both sides accepted the division.

Life in Trịnh-Ruled North Vietnam

In the North, the Trịnh family kept the Lê royal family on the throne but held all the real power. They tried to restore a good government system. They also had peaceful relations with China. The Trịnh developed farming, collected taxes, and traded with other countries. Catholicism grew, with many Christians in the North.

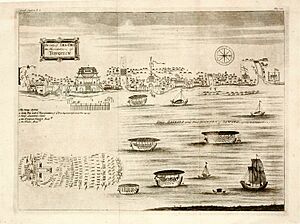

The population grew, and trade increased. The Trịnh even traded with European companies like the Dutch East India Company. Hanoi, the capital, was a large city with over 100,000 people.

Life in Nguyễn-Ruled South Vietnam

Unlike the North, the Nguyễn lords in the South promoted Vietnamese Buddhism. They built many pagodas and shrines.

The South's economy relied heavily on sea trade, especially with Japan and China. The port of Hoi An became very important. Japanese, Chinese, and European ships came to trade. This trade brought a lot of money to the Nguyễn court. The Nguyễn also welcomed Portuguese traders. They even hired Westerners to help them, like a doctor and teachers of math and astronomy. The economy grew, attracting more Vietnamese settlers to the South.

Problems in Vietnam in the 1700s

Troubles in Trịnh's North Vietnam

In the North, problems started in the early 1700s. The population grew, but international trade slowed down. There were famines and floods, forcing many people to leave their homes. The Trịnh lords tried to change the tax system, but it often hurt the poor. Rich nobles took land from poor peasants.

Buddhism became more important, and Trịnh rulers spent a lot of money building and repairing temples. This caused unrest among the people. Many revolts broke out in the 1730s. Some Lê princes even tried to take back power. One prince, Lê Duy Mật, fought the Trịnh for 30 years. By the mid-1700s, many villages in the North were empty due to these problems.

Troubles in Nguyễn's South Vietnam

The South also faced economic problems. There was a shortage of copper coins, which hurt trade. The Nguyễn lords tried to make zinc coins, which were cheaper, but this caused prices to rise a lot. Gold became more expensive, and rent increased. There were also major famines in 1752 and 1774.

The Nguyễn armies also fought many costly wars in Cambodia. Tensions between ethnic Khmer and Vietnamese people in the Mekong delta led to violence. In the early 1770s, the Nguyễn lord Nguyễn Phúc Thuần raised taxes very high to solve the economic crisis. Officials warned him that "the people's misery has reached an extreme degree." These problems and high taxes likely led to the Tây Sơn rebellion.

The Rise of the Tây Sơn Brothers

How the Revolt Began

The Tây Sơn brothers came from the Tây Sơn district in Bình Định Province. Their father was a betel trader. The eldest brother, Nguyễn Nhạc, worked as a tax collector. He also traded betel nuts. People say he couldn't collect taxes because of the bad economy and people's unhappiness.

The Nguyễn government in Huế placed very heavy taxes on the area. In 1765, a regent named Trương Phúc Loan took power in the Nguyễn capital, making things even worse. In 1771, Nguyễn Nhạc decided to flee into the Central highlands to avoid arrest. He took his brothers and supporters with him. His teacher encouraged him, saying he was meant to lead a "righteous uprising."

Starting the Uprising (1771–1773)

In 1771, Nguyễn Nhạc and his followers revolted against the Nguyễn lord's government. Their movement attracted many different groups: highlanders, Cham people, Vietnamese, and even Chinese pirates. All of them had their own reasons to be unhappy. Many ethnic Chinese traders were upset about the decline in trade and high taxes. They hoped the Tây Sơn would improve things.

The region where the Tây Sơn brothers hid was perfect for them. It was remote and easy to defend. It was also on important trade routes and had resources like wood, iron, and sulfur. Nguyễn Nhạc already knew many people there who helped him and joined his army. For two years, they grew their forces. Eventually, Nhạc decided his army was ready to fight the Nguyễn forces directly in the lowlands.

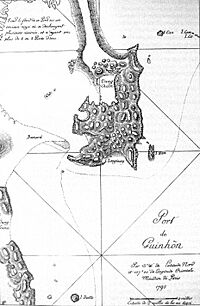

Taking Qui Nhơn (1773)

To gain control of the coastal areas, the Tây Sơn needed to capture Qui Nhơn, a walled city. They didn't have enough men or weapons for a direct attack. So, they used a trick like the Trojan horse. In September 1773, Nguyễn Nhạc pretended to be captured. His supporters put him in a cage and presented him to the city officials. The officials were happy and brought the cage inside the city.

That night, Nhạc got out of the cage, took a guard's sword, and attacked the guards. He opened the city gates, letting his soldiers rush in. The Tây Sơn troops quickly defeated the city's military. The governor fled so fast he dropped his official seal. Taking Qui Nhơn gave the Tây Sơn more power and resources. It also gave them control over a large part of the coast. The Tây Sơn leaders made more people work for them, including women, children, and Buddhist monks. By 1774, the Tây Sơn rebels had grown to more than 25,000 soldiers.

Wars from 1773 to 1785

The Fall of Nguyễn-Ruled Cochinchina

After their victory at Qui Nhơn, the Tây Sơn forces took several nearby areas. Meanwhile, the Trịnh lords in the North saw an opportunity. They invaded the South in late 1774, pretending to help the Nguyễn but really wanting to take over. The young Nguyễn ruler, Nguyễn Phúc Thuần, and his nephew, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh, fled to Saigon and the Mekong Delta. This area became their base for resistance.

The Trịnh forces captured Huế and moved towards the Tây Sơn. Caught between the Trịnh in the north and the Nguyễn in the south, Nguyễn Nhạc surrendered to the Trịnh in May 1775. The Trịnh army then turned back to Huế, where many of their soldiers died from an epidemic. A scholar named Lê Quý Đôn described the great wealth the Trịnh found in Huế, including thousands of imported coins.

Tây Sơn Campaigns in Saigon

The next ten years saw many battles between the Tây Sơn and Nguyễn forces. The main battleground was Saigon. The wars were often affected by the monsoon winds, which controlled when naval forces could move. The Tây Sơn brothers preferred to stay near their home base in Qui Nhơn. They often captured Saigon but would leave quickly, making it easy for the Nguyễn to take it back.

Local Vietnamese merchants supported the Tây Sơn. They disliked the competition from ethnic Chinese merchants who were strong in southern ports like Gia Định and Hà Tiên. In 1775, two-thirds of the Tây Sơn army was led by ethnic Chinese generals, Lý Tài and Tập Định. However, these Chinese forces were not fully loyal. Within two years, Lý Tài and his "Hoà Nghĩa army" left the Tây Sơn and joined the Nguyễn forces. Lý Tài's army, made of Chinese settlers, became a strong force for the Nguyễn.

The Tây Sơn captured Saigon for the first time in 1776, led by the youngest brother, Nguyễn Lữ. But the Nguyễn forces soon recaptured it. In 1777, Nguyễn Nhạc sent Lữ and Nguyễn Huệ to take Saigon again. The Tây Sơn, led by Huệ, destroyed most of the Nguyễn army and killed almost all of the Nguyễn royal family. They also defeated the Hoà Nghĩa army, and Lý Tài was killed. Huệ then returned to Qui Nhơn, leaving troops to hold Saigon.

In 1778, Nguyễn Nhạc declared himself "Heavenly King" at Chà Bàn, near Qui Nhơn. He made Chà Bàn his capital. The Trịnh recognized him but gave him a lower rank. Nhạc wanted to conquer the former Nguyễn territories that the Trịnh still held.

Nguyễn Survivors in South Vietnam

The only survivor of the Nguyễn royal family massacre was Prince Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (1761–1820). He was hidden by a Catholic priest, Pigneau de Behaine, who became his adviser. They hid in the swamps and on islands to escape the Tây Sơn. When the Tây Sơn left Saigon, Nguyễn Ánh gathered his remaining forces and recaptured the city in early 1778.

With support from local Nguyễn supporters, Nguyễn Ánh declared himself king in 1780. He made alliances and tried to get help from Siam, India, France, and Melaka to get supplies. From 1778 to 1781, both sides focused on strengthening their positions. In 1781, Nguyễn Ánh attacked the Tây Sơn at Nha Trang but failed. In May 1782, Nguyễn Nhạc and Nguyễn Huệ counterattacked with 100 warships, attacking Saigon.

When the Tây Sơn entered Saigon, one of Nhạc's key commanders was killed by a Chinese general fighting for the Nguyễn. Nhạc then ordered his troops to attack Chinese settlers in Saigon. Tây Sơn troops burned shops and killed thousands of Chinese residents. This showed the Tây Sơn's anger at the Chinese community for supporting the Nguyễn. After this victory, the Tây Sơn leaders returned north in June. Nguyễn Ánh counterattacked and recaptured the city a few months later.

Nguyễn Ánh, France, and the Siamese Invasion of 1785

The French first helped Nguyễn Ánh in 1777 when he fled from the Tây Sơn. Pigneau de Behaine and his Catholic community helped him hide and get weapons. Pigneau described his military role in helping Nguyễn Ánh.

In 1782, a major Siamese invasion in Cambodia led to a new king, Rama I, in Siam. In March 1783, Huệ and Lữ attacked Saigon again, defeating the Nguyễn army and chasing Nguyễn Ánh away. A storm destroyed much of the Tây Sơn navy, allowing Nguyễn Ánh to escape to Phú Quốc Island. Pigneau de Behaine visited the Siamese court in Bangkok in late 1783. Nguyễn Ánh also went to Bangkok in February 1784, where he got help from the Siamese king.

In January 1785, Nguyễn Ánh launched another attack from Siam with 20,000 Siamese soldiers and 300 ships. They moved through Cambodia and the Gulf of Siam to attack southern Vietnam. But the Tây Sơn were ready. Nguyễn Huệ lured the Siamese navy into a trap on the Mekong River near Mỹ Tho. He destroyed all the Siamese ships, leaving only a thousand Siamese troops alive. This was a huge defeat for Nguyễn Ánh, who fled back to Bangkok. Nguyễn Ánh then decided to seek help from Western powers.

Tây Sơn Takes Over the North (1785–1788)

The Fall of the Trịnh Lords

After defeating Nguyễn Ánh, Nguyễn Nhạc saw a chance to expand his power into the Trịnh-held territories in the North. The Trịnh were weak due to famines, floods, and political fights. The death of Trịnh Sâm in 1782 led to more instability. A Trịnh defector, Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh, encouraged Nhạc to attack the North.

In June 1786, Nguyễn Nhạc sent an army north towards Huế, led by Nguyễn Huệ and Chỉnh. Huệ led a naval force, and Chỉnh led a land attack. Huế quickly surrendered to the Tây Sơn, and many Trịnh defenders were killed. Soon, all of Thuận Hoá fell to the Tây Sơn. Huệ was ordered to stop at the traditional border, but Chỉnh convinced him to keep going.

Huệ and Chỉnh attacked northward with 400 ships. They took public rice stores along the way. Chỉnh's troops met little resistance. Panic spread in the capital, Thăng Long. The northern ruler, Trịnh Khải, fled and took his own life, ending over 200 years of Trịnh rule. Huệ's armies marched into Thăng Long on July 21, 1786. People called Huệ "Chế Bồng Nga" because of his terrifying attack from the south.

In the capital, the Tây Sơn rebels opened granaries and gave food to the people. Huệ met with the old Lê emperor, Lê Hiển Tông, and offered his submission. The emperor gave Huệ the title of general and a Lê princess (Lê Ngọc Hân) in marriage. The emperor died a few days later, and his nephew, Lê Chiêu Thống, became the new emperor. In late August, the Tây Sơn brothers returned south, leaving Chỉnh behind. Chỉnh tried to build his own power base in Nghệ An.

Civil War Among the Three Brothers (1787)

After returning south, Nguyễn Nhạc divided the newly won territory among his three brothers. The weakest brother, Nguyễn Lữ, ruled Saigon and the Mekong Delta. Nhạc kept the central region for himself, ruling as Emperor Thái Đức from Qui Nhơn. Nguyễn Huệ was given Huế and Nghệ An, becoming the Bắc Bình Vương (Northern Pacification King).

However, there were tensions between the brothers, especially between Nhạc and Huệ. These tensions led to a violent fight from February to June 1787. Huệ quickly gathered an army of 50,000 peasants. He besieged his older brother at Chà Bàn and won, forcing Nhạc to give up more territory. In the same year, Nguyễn Huệ started drafting 15-year-olds into his army because many of his soldiers had left due to his reported "cruelty."

Problems in Northern Vietnam (1786–1788)

Meanwhile, in the North, Emperor Lê Chiêu Thống was a weak ruler. Survivors of the Trịnh family tried to regain power. The emperor secretly asked Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh for help. Chỉnh saw a chance to increase his own power. He gathered a 10,000-man army and marched towards Thăng Long in December 1786. By January, he had defeated the Trịnh army and became the new master of the North.

Huệ was angry at Chỉnh's actions and ordered him to return, but Chỉnh refused. Chỉnh also advised the emperor to demand Nghệ An back from Nguyễn Huệ. Huệ angrily refused and sent his aide Võ Văn Nhậm to Thăng Long to capture Chỉnh. Nhậm easily took the capital in the fall of 1787, captured Chỉnh, and killed him. But then Nhậm became ambitious himself. Ngô Văn Sở, another Tây Sơn general, told Huệ that Nhậm was planning to betray him. Huệ trusted Sở and attacked Thăng Long again in the spring of 1788, capturing and beheading Nhậm.

China Invades Northern Vietnam

After fleeing his capital, Emperor Lê Chiêu Thống asked the Chinese Qing emperor for help. The Qianlong Emperor was hesitant, but his ambitious governor, Sun Shiyi, convinced him that invading Vietnam would be easy. In late October 1788, a Chinese army of up to 200,000 men crossed into northern Vietnam. They occupied Thăng Long (Hanoi) without a fight and briefly restored the Lê dynasty.

The Tây Sơn forces, led by Ngô Văn Sở, retreated to Thanh Hoá and asked Nguyễn Huệ for help. Huệ decided that the Lê family had lost their right to rule. In response, Huệ crowned himself Emperor Quang Trung (r. 1788–1792) in Huế. The new Tây Sơn emperor quickly gathered another army and marched north. He sent a message to the Chinese general asking him to leave, but the general tore up the message and killed the envoy.

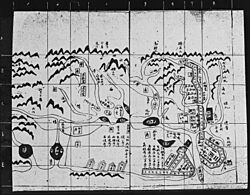

Meanwhile, the Chinese troops were celebrating the Lunar New Year. Nguyễn Huệ ordered his troops to celebrate the New Year early. On New Year's Day 1789, the Tây Sơn forces launched a surprise attack with 100,000 men and 100 war elephants. They attacked the Qing troops in Thăng Long who were still celebrating. The Chinese army was completely unprepared and easily defeated. Thousands of fleeing Qing troops drowned in the Red River. Survivors retreated north with the Lê royal family.

While the Tây Sơn were fighting the Chinese in the North, Nguyễn Ánh and his Siamese allies retook Saigon and the Mekong Delta in late 1788. He easily drove out Nguyễn Lữ, who fled to Qui Nhơn and died shortly after.

Quang Trung in Power (1789–1792)

After his victory in 1789, Quang Trung worked to secure his power. First, he made sure to have lasting peace with China. He sent diplomats who convinced the Chinese court to stop trying to restore the Lê family. The Chinese ruler recognized Quang Trung as the new "National King of An Nam." A Vietnamese group even visited the Chinese court in Beijing. Quang Trung sent a look-alike in his place to avoid a risky journey. This helped ensure peaceful relations with China.

With peace with China, Quang Trung focused on problems at home. Years of war had damaged the economy and society. Quang Trung ordered displaced peasants to return to their fields and set taxes to encourage farming. He also ordered a nationwide census and a system of identity cards. Anyone without a card could be forced into the army. Quang Trung also started a project to translate important Chinese books into Chữ Nôm, the Vietnamese writing system. He tried to revive the education system and examinations.

Quang Trung's generals also invaded Laos twice. He also tried to make trade deals with European outposts in Macao and the Philippines. He wanted them to trade with his government instead of Nguyễn Ánh's. These efforts were mostly unsuccessful. However, he did arrange new trading markets with China along the border. The Tây Sơn also supported a growing network of Chinese pirates who fought against Nguyễn Ánh. This pirate network only ended when Nguyễn Ánh defeated the Tây Sơn in 1802.

Tây Sơn–Nguyễn War (1792–1802)

The Tây Sơn Weaken

Quang Trung and Nguyễn Lữ both died in 1792. Quang Trung, only 40, died unexpectedly while planning a big attack on Nguyễn Ánh. His 11-year-old son, Nguyễn Quang Toản, became Emperor Cảnh Thịnh. He ruled under the guidance of his uncle, Bùi Đắc Tuyên, who faced opposition from other Tây Sơn commanders. The next year, the elder Tây Sơn leader Nguyễn Nhạc died. After Nhạc's death, his young son, Nguyễn Văn Bảo, was named his successor but without imperial power.

The Tây Sơn government struggled with corruption and limited administrative skills. Even though their main leaders were gone, Tây Sơn generals continued to fight the Nguyễn. Emperor Cảnh Thịnh made some changes, like canceling his father's unpopular "trust card" program. He also tried to count the population and consolidate Buddhist temples. However, he started to crack down on Christians in 1795, suspecting them of supporting the Nguyễn. Many northern scholars who had helped Quang Trung slowly left the new government. The growing military threat from the Nguyễn also took up much of the court's attention.

Nguyễn Retake the Mekong Delta

After their defeat in 1785, the Nguyễn fled to Bangkok. There, Nguyễn Ánh and his followers planned their return. Nguyễn Ánh asked Pigneau to get French help. Pigneau took Nguyễn Ánh's five-year-old son, Prince Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh, with him to France. In 1787, they signed the Treaty of Versailles with King Louis XVI of France. France promised to send ships and soldiers in return for land in Vietnam. However, the French official in Pondicherry canceled the plan due to France's financial problems before the French Revolution.

Pigneau, not giving up, used his own money to gather French mercenaries and ships. He sailed to Vietnam in 1789. By this time, Nguyễn Ánh had already returned from Bangkok and retaken Saigon. Pigneau returned with 14 French officers, 360 soldiers, and 125 sailors. They began training Nguyễn Ánh's troops in modern artillery and European fighting methods.

In 1790, Olivier de Puymanel, a French officer, built the Citadel of Saigon and later the Citadel of Dien Khanh using European designs. In 1791, a French missionary showed Nguyễn Ánh how to use balloons and electricity. By 1792, Puymanel commanded 600 men trained in European techniques and trained 50,000 of Nguyễn Ánh's soldiers. Nguyễn Ánh also built a strong fleet with European warships. He used his new naval workshop to improve his navy, which was smaller than the Tây Sơn's. Siam also helped Nguyễn Ánh by encouraging Lao kings to fight the Tây Sơn. Chinese, Malay, Cambodian, Siamese, and Western troops joined the Nguyễn army.

From 1787 to 1792, Nguyễn Ánh strengthened his control in the South. Nguyễn Nhạc launched attacks, but none could remove the Nguyễn from their southern base. The Nguyễn traded with the Chinese for rice, cotton, silk, iron, and sulfur. With Western help, Nguyễn Ánh got weapons and ammunition from places like Malacca, Java, the Philippines, and Bengal.

Nguyễn Attacks (1792–1793)

The military campaigns in the 1790s were called "monsoon wars" because they depended on coastal winds. Moving by sea was faster, but it also meant attackers couldn't stay long or easily hold their victories. This made Nguyễn Ánh's progress slow, frustrating his European advisers.

The Nguyễn's main target was the southern Tây Sơn capital near Qui Nhơn and its port, Thị Nại. In summer 1792, the Nguyễn attacked and surrounded Nguyễn Nhạc at Qui Nhơn. Jean-Marie Dayot led the Nguyễn forces, defeating the Tây Sơn fleet. Nhạc's commanders lost their navy. A second Nguyễn siege in 1793 was only stopped when Nhạc's nephew, Emperor Cảnh Thịnh, sent 18,000 troops, 80 elephants, and 30 war junks as reinforcements. From 1794, Pigneau himself joined all campaigns, even organizing the defense of Diên Khánh against a larger Tây Sơn army. The destruction of Nhạc's fleet in 1792 and his death in 1793 were major blows to the Tây Sơn. After this, the Tây Sơn relied more on Chinese pirates for naval strength.

The Nguyễn's northern attack led to several Cham leaders leaving the Tây Sơn. In 1794, they betrayed and killed the Tây Sơn's main Cham ally, the king of Champa. The Nguyễn then appointed their own Cham leader.

Tây Sơn Counterattack (1795)

In spring 1795, Tây Sơn troops counterattacked, pushing the Nguyễn back towards Bà Rịa. This was the last major Tây Sơn attack south. The Tây Sơn forces were pushed back by an army of Khmers and other Nguyễn forces. Meanwhile, Nguyễn Ánh waited with his fleet for the winds to change. He sailed to Nha Trang to help Diên Khánh and then to Phú Yên to block the Tây Sơn. For four months, fighting raged. The Tây Sơn were defeated and withdrew. An army of uplanders also helped Nguyễn Ánh win in Phú Yên.

Nguyen Campaign in Da Nang (1797)

In spring 1797, a Nguyễn attack went further north, into the heart of Tây Sơn territory. They occupied Da Nang for two months before leaving.

First Battle of Qui Nhơn (1799)

Nguyễn Ánh spent late 1797 dealing with Chams who had served the Tây Sơn. Siamese troops helped. Discussions began to coordinate Siamese and Lao troops with Nguyễn Ánh's future campaigns. He also tried to improve relations with China.

In 1799, Nguyễn Ánh launched a two-part attack on Huế and Qui Nhơn. His fleet included French-commanded ships, galleys, war junks, and transport boats. He sailed ahead and captured the port of Qui Nhơn, helped by disagreements among Tây Sơn generals. He sent Lê Văn Duyệt to block Tây Sơn armies coming south. Lê Văn Duyệt got local leaders to help block the mountain passes. The Tây Sơn armies panicked when a scout shouted "nai!" (deer), which was also slang for Nguyễn soldiers. This caused a stampede.

Nguyễn Ánh's fleet defeated a Tây Sơn fleet, and his land forces took Nguyễn Nhạc's old capital, Chà Bàn. In June, Qui Nhơn was finally captured by the Nguyễn. Ánh renamed the city Bình Định ("Pacification Established"). The Tây Sơn, with help from pirates, then besieged Qui Nhơn for a year. They couldn't retake the city but captured nearby Phú Yên, using it as a base. The young Tây Sơn ruler, Cảnh Thịnh, fled north to gather support. He changed his reign name to Bảo Hưng (Defending Prosperity) and prepared the North for defense.

Despite the setback, the Nguyễn continued their advance. Nguyễn Ánh spent months in Bình Định, organizing supplies, recruiting soldiers, and setting up administration. Over a thousand men were trained for artillery. In October 1799, Pigneau, Nguyễn Ánh's trusted adviser, died. Nguyễn Ánh gave him an honorable burial. The French forces continued to fight with Nguyễn Ánh.

Second Battle of Qui Nhơn (1801)

After dealing with a Cham uprising and mobilizing Khmers, Nguyễn Ánh marched his land forces north in summer 1800. Ships with rice from his ally, Rama I, joined his supply fleet. Nguyễn Ánh arrived at Nha Trang and met his land forces. He sent them into Phú Yên. News arrived that his Lao allies were attacking Nghệ An. He ordered Lê Văn Duyệt to advance. Lê Văn Duyệt pushed into Bình Định but was stopped by Tây Sơn walls. However, Nguyễn Ánh's ships captured a Tây Sơn supply fleet and Chinese pirates.

A few weeks later, the Tây Sơn suffered a major naval defeat at Qui Nhơn in February 1801. The Nguyễn captured 13,700 Tây Sơn soldiers. French officers played an active role. These victories greatly strengthened Nguyễn Ánh's position. Prince Cảnh died of smallpox. Nguyễn Ánh sailed to Hội An, gathering local men. He then sailed to Da Nang Bay and advanced to Huế. Tây Sơn forces offered little resistance, and Huế quickly fell. Emperor Cảnh Thịnh fled north.

However, the Nguyễn land forces were still blocked in Qui Nhơn by a strong defense led by Bùi Thị Xuân and Trần Quang Diệu. The Tây Sơn forces even recaptured Qui Nhơn in summer 1801 after a 17-month fight. They held it only briefly. This was their last, though meaningless, victory. European observers reported over 54,000 casualties in Qui Nhơn.

The Last Tây Sơn Resistance

The final blow came in spring 1802. Nguyễn Ánh's forces bypassed the Tây Sơn in Qui Nhơn and sailed directly to the North. Despite some resistance, the Nguyễn easily landed and marched quickly towards Thăng Long, where Emperor Cảnh Thịnh had taken refuge. Nguyễn Ánh entered the city on July 20, 1802, starting the last Vietnamese dynasty. There were still small Tây Sơn attacks, but the Nguyễn began to unite the country.

After the Nguyễn victory, surviving Tây Sơn leaders were captured. Some, including Cảnh Thịnh and his family, and the female general Bùi Thị Xuân, were executed. Others were publicly whipped. Nguyễn Ánh even ordered the remains of Nguyễn Huệ and Nguyễn Nhạc to be dug up and ground into powder. This showed that the Tây Sơn era was truly over.

Aftermath of the Wars

The Nguyễn Dynasty Begins

In June 1802 in Huế, Nguyễn Ánh declared himself the Gia Long emperor. He renamed the country from "Đại Việt" to "Việt Nam." After 25 years of fighting, Gia Long had united Vietnam, from China in the north to the Gulf of Thailand in the south. He became the first Vietnamese ruler to control such a large area.

The new Nguyễn leader adopted a government system similar to the successful one from the 15th century. However, the Nguyễn victory didn't fully solve the problems that caused the Tây Sơn wars. Peasant unhappiness continued. Tây Sơn loyalists still caused unrest, even though the Nguyễn tried to erase all traces of Tây Sơn rule. The remaining sons and grandsons of Nguyễn Nhạc were found and executed in 1830.

Roles of Different Groups

Ethnic Chinese played a big role in the civil war. Many Chinese refugees had settled in southern Vietnam after the fall of the Ming dynasty in 1679. The Nguyễn lords allowed them to settle, seeing them as useful for populating new areas. At the start of the Tây Sơn rebellion, most Chinese joined and helped finance the Tây Sơn. However, some Chinese, like Lý Tài, later betrayed the Tây Sơn and joined the Nguyễn. Tây Sơn armies sometimes attacked Chinese communities, especially in Saigon in 1782, where thousands were killed. But in the 1790s, the Tây Sơn started using Chinese pirates to fight the Nguyễn.

Chinese groups, like the Minh Hương, became important in the new Nguyễn government and economy. Their farming exports helped the South grow.

Vietnamese Catholics were also involved. There are stories that the Tây Sơn brothers came from a Christian family. However, the only Tây Sơn leader known to have persecuted Christians was Nguyễn Nhạc. Some missionaries said that Quang Trung was tolerant of Christians, and a powerful official in his court was Christian and protected them. The youngest brother, Nguyễn Lữ, was even very pro-Christian.

After Quang Trung's death in 1792, the Tây Sơn became suspicious of Christians and missionaries because French and Catholic people were helping Nguyễn Ánh. In 1795 and 1798, the Tây Sơn government issued orders against Catholics. They feared Christians were supporting the Nguyễn. In 1798, a Vietnamese Christian was executed, marking the first public execution of a Christian since 1782.

When Nguyễn Ánh entered Hanoi in 1802, it ended a chaotic time for Vietnam. But for Vietnamese Christians, it didn't bring religious freedom. Even though Nguyễn Ánh owed debts to French missionaries, his rule continued the tensions between the state and the Christian faith.

Other ethnic groups also played roles. The Tây Sơn relied on the Chams because their home area was close to Cham territory. Some Cham leaders joined the Tây Sơn, hoping to regain their old political power. In 1788, a Khmer named Ốc Nha Long joined the Tây Sơn with boats.

Legacy of the Tây Sơn Wars

The Tây Sơn dynasty was short-lived, but it had unique ideas about Vietnamese history. They emphasized Cham history and Vietnamese culture. Quang Trung saw himself as part of a long line of Vietnamese leaders who fought Chinese dynasties. He said, "...Throughout all these periods, the South [Vietnam] and the North [China] were clearly separated." The Tây Sơn even honored two ancient Vietnamese female generals. In 1798, they started a new history project to rewrite Vietnam's past.

However, historians say the Tây Sơn dynasty wasn't truly revolutionary. Its government was similar to the Trịnh and Nguyễn regimes. Quang Trung's actions, like appealing to northern scholars and making peace with China, show he was practical, not just ideological. His son, Emperor Cảnh Thịnh, also made practical decisions, like taking a census and trying to control Buddhist temples.

After the Tây Sơn wars, the Nguyễn dynasty tried to portray the Tây Sơn as mere "rebels" and "bandits" with no right to rule. But they couldn't erase the fact that the Tây Sơn had overthrown the Lê and ruled much of the country for over a decade. Later, in the 20th century, some Vietnamese historians saw the Tây Sơn uprising as a nationalist revolution. They said it aimed to overthrow corrupt forces, unite the country, defend against outside threats, and promote Vietnamese culture. This view fit the political goals of North Vietnam after 1954. However, a closer look shows that the Tây Sơn movement didn't have a clear ideology, and its political impact wasn't truly revolutionary. Most basic political, economic, and social structures remained the same.

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |