Tarkine facts for kids

Quick facts for kids takayna / TarkineTasmania |

|

|---|---|

| LGA(s) |

|

The Tarkine (also known by its Aboriginal name: takayna) is a special wild area in north-west Tasmania, Australia. Many people believe it's a very important wilderness area. The Tarkine is famous for its amazing natural beauty and unique features. It has the largest area of ancient cool-temperate rainforest in Australia, which is like a living link to a supercontinent called Gondwana.

This area also has a rich history, especially for its early mining days. But even more special are the many ancient Aboriginal sites found here. The Australian Heritage Council has even called it "one of the world's great archaeological regions" because of these important sites.

Contents

Where is the Tarkine?

The Tarkine is located in the north-west part of Tasmania. It's generally thought to be the area between the Arthur River in the north and the Pieman River in the south. To the west, it meets the ocean, and to the east, it's bordered by the Murchison Highway.

The Tasmanian government officially recognized the name "Tarkine" in 2013. Even though you might not see the name on all maps, it's often talked about in the news. This is because there are ongoing discussions about protecting the area versus allowing mining and logging.

You can visit the Tarkine from several places. Some common entry points are Sumac Road from the north, Corinna in the south, Waratah in the west, and Wynyard from the north-east. Wynyard has an airport and good roads that lead into the Tarkine.

What does 'Tarkine' mean?

The name "Tarkine" was created by groups who wanted to protect the environment. It started being used around 1991. The name is a shorter version of "Tarkiner," which is how people pronounced the name of one of the Aboriginal tribes. This tribe lived along the western Tasmanian coastline, from the Arthur River to the Pieman River, long before Europeans arrived.

Nature and ancient history

The Tarkine is a truly wild place with huge, untouched areas of cool temperate rainforest. These rainforests are very rare and the Tarkine holds Australia's largest single area of them. It has about 1,800 square kilometers of rainforest, plus other types of forests and plant communities. You can find dry forests, woodlands, and wetlands here.

This area is also home to many different plants, including at least 151 types of liverworts and 92 types of mosses. It's a habitat for many animals too, including 28 types of mammals, 111 kinds of birds, 11 reptiles, 8 frogs, and 13 freshwater fish. More than 60 rare, threatened, and endangered plant and animal species live in the Tarkine.

The Tarkine also features many rivers, mountains, unique cave systems made of magnesite and dolomite, and Tasmania's largest basalt plateau that still has its original plants. There are also large sand dunes that stretch several kilometers inland. Some of these dunes contain ancient Aboriginal middens, which are mounds of shells and other remains left by Aboriginal people.

The Tarkine was very important in Tasmania's early mining history. You can still see signs of old mining activities in many rivers and creeks where people searched for gold, tin, and osmiridium. Today, there are about 600 historic mining sites in the area. Most of these were small operations, but larger mines existed at places like Luina, Savage River, and Mt Bischoff.

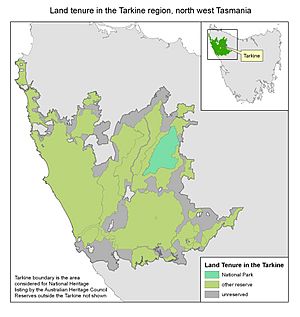

Part of the Tarkine is protected within the Arthur-Pieman Conservation Area, which is managed by the Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service.

Protecting the Tarkine

Efforts to protect the Tarkine began way back in the 1960s. A local mayor, Horace Arnold 'Jim' Lane, suggested creating a 'Norfolk Range National Park'. His idea was ahead of its time, but it didn't happen then.

From the late 1990s, more people around Australia and the world started paying attention to the Tarkine. It became a focus for environmental protests, similar to the famous campaigns to save the Franklin River in Tasmania and the Daintree Rainforest in Queensland. In 2005, the Australian government added 70,000 hectares to protected areas in the Tarkine, which was a big step forward.

A large part of the Tarkine, including the Savage River National Park, is already part of Tasmania's protected land system. This system helps protect the biggest continuous area of cool temperate rainforest in Australia.

Laws and protected areas

Tasmania has a good system for managing its protected areas. Laws like the Nature Conservation Act 2002 and the National Parks and Reserves Management Act 2002 help decide how these areas are used.

There are eight different types of public protected areas in Tasmania, each with its own rules. Just because an area is protected doesn't mean all activities are banned. For example, National Parks protect nature but also allow for eco-friendly tourism. Some areas, like Regional Reserves and Conservation Areas, aim to protect nature while also allowing for mining and careful use of other natural resources, like harvesting special types of timber.

Proposed National Heritage listing

In December 2009, the Tarkine was temporarily listed as a National Heritage Area. This was done quickly because there was a plan to build a road through an old-growth forest that would harm the area's natural beauty. However, in December 2010, the Environment Minister at the time, Tony Burke, let this temporary listing expire. This happened even though the Australian Heritage Council recommended making the listing permanent.

Later, in February 2013, Minister Tony Burke decided to only list a smaller coastal section of the Tarkine (21,000 hectares) as National Heritage, instead of the much larger area (433,000 hectares) that the Australian Heritage Council had suggested. This decision worried conservation groups, who felt it left much of the Tarkine unprotected from mining.

Proposed Tarkine National Park

An environmental group called the Tarkine National Coalition wants the Tarkine to be officially declared a national park. This would give it the highest level of protection. The process for this has been complex due to agreements between the Australian and Tasmanian governments about forests.

In 2011, an agreement was signed to help Tasmania move away from logging native forests and protect large areas of important natural vegetation. The then-Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, said this agreement would better protect the Tarkine, calling it "very important."

However, after a change in the Tasmanian government in 2014, some of these plans were changed. While some areas protected in 2013 remain safe, other areas that were meant to become reserves were reclassified. This means some parts of the Tarkine might still be used for forestry after 2020.

The campaign to make the Tarkine a National Park is still ongoing.

Special timber harvesting

Tasmanian laws allow for the careful harvesting of special timbers in some parts of the Tarkine. These areas include Regional Reserves, Conservation Areas, and Future Potential Production Forest (FPPF) land. It's important to know that mining is also allowed in these areas.

Environmental groups have sometimes supported the idea of harvesting special timbers in a sustainable way. This means taking only a small amount of wood without harming the forest in the long term. For example, former Senators Bob Brown and Christine Milne, who are Greens politicians, have called for specific areas to be set aside for "sustainable selective logging of high-quality, specialty timbers."

Research into how to regrow rainforests after harvesting began in north-western Tasmania in 1976. Scientists studied different ways to cut trees and help new ones grow back. One such study in the Tarkine, called the Sumac forest harvest trials, started in 1976. These trials aimed to find the best methods for regrowing Myrtle-dominated forests after harvesting, to ensure a continuous supply of special timbers.

These trials were successful, and the research helped create rules for how to harvest timber sustainably. In 2015, experts from the World Heritage Committee visited the Sumac trial site and said what they saw was "world's best practice."

A study from 2014-2017 looked at where special timbers are located and how much can be harvested sustainably each year. This study used advanced technology like LiDAR (which uses lasers to map the land) to figure out that there are about 14.3 million cubic meters of special timbers. This research helps plan for sustainable harvesting in areas of the Tarkine where it's allowed.

Because a lot of special timber forests were included in the 2013 Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area extension, the Tarkine remains a key source for these culturally important timbers.

Mining in the Tarkine

The Tarkine has a long history of mining. Areas like Corinna, Long Plains, and the Savage, Donaldson, and Whyte rivers were important goldfields starting in the 1870s. Tasmania's two largest gold nuggets were found near the Whyte and Rocky rivers! Tin mining was also big in the Mt Bischoff – Waratah area, and the Mt. Bischoff mine was once one of the richest tin mines in the world.

Historically, about 600 small mines operated in the Tarkine, mostly sifting gravel from riverbeds. Mining has continued in the Tarkine since the 1870s. Today, two modern mines are still working: a small silica quarry and a large open-pit iron ore mine at Savage River. Both of these existing mines are outside the proposed Tarkine National Park boundary.

However, there are also 38 exploration licenses for new mining in the Tarkine, and 10 new mines were proposed between 2012 and 2017. Most of these proposed mines would be open-cut mines.

Mining in the Tarkine is a very debated topic. Conservationists are against new mines because they worry about the environmental damage caused by modern mining methods. They point to problems like acid mine drainage (AMD), which is when chemicals from mines pollute rivers. For example, the Whyte River turned orange and lost its aquatic life for six kilometers due to the now-closed Cleveland mine. Similar problems have happened downstream from the Savage River mine and the closed Mt Bischoff mine.

Mining companies argue that new mines would only affect about 1% of the Tarkine. But conservationists say the impact is much larger when you consider transport routes and damage to water systems. Groups like the Tarkine National Coalition are actively campaigning against new mines and mining exploration in the area. On the other hand, many local people support mining because it creates jobs and helps the economy.

|

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |