Tasmanian emu facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tasmanian emu |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 1910 restoration by John Gerrard Keulemans, based on a skin at the British Museum, posed after a photograph of the mainland emu | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Casuariiformes |

| Family: | Casuariidae |

| Genus: | Dromaius |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: |

†D. n. diemenensis

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Dromaius novaehollandiae diemenensis Le Souef, 1907

|

|

|

|

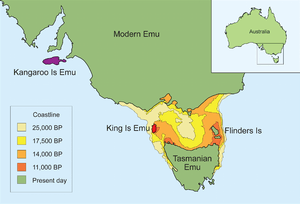

| Geographic distribution of emu taxa and historic shoreline reconstructions around Tasmania | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Dromaeius diemenensis (lapsus) Le Souef, 1907 |

|

The Tasmanian emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae diemenensis) was a type of emu that is now extinct. It lived on the island of Tasmania. This emu became separated from other emus during the Late Pleistocene ice age. Unlike other island emus, like those on King Island or Kangaroo Island, the Tasmanian emu population was quite large. This meant they did not suffer from problems caused by having a small population size.

The Tasmanian emu disappeared around 1865. The Australian government officially listed it as presumed extinct in 1997. Most of what we know about this emu comes from old writings from the 1800s. We also learn from the few emu specimens kept in museums. One challenge for researchers is that the emu was called many different names back then. Early settlers sometimes called it 'emue' or 'emew'. Some even thought it was a 'cassowary' or an 'ostrich'. The Indigenous people had their own names for it. For example, in the Oyster Bay language, it was called "Pun.nune.ner."

Contents

What the Tasmanian Emu Looked Like

Scientists are not completely sure if the Tasmanian emu was a totally different species. Some even debate if it was a distinct subspecies. This is because it looked very similar to the emus on mainland Australia. Its size was about the same as mainland emus. Some people thought its neck was whiter and had fewer feathers. However, these features can also be seen in some mainland emus.

Where the Tasmanian Emu Lived

There is a lot of proof that Tasmanian emus were very common in Van Diemen's Land (which is what Tasmania was called). In 1823, a writer named John Latham said that groups of 70 or 80 emus were often seen. An old newspaper from 1803 reported that there were "abundance of Emues" near the first settlements.

In 1804, another explorer found that "the emue [is] plentiful." A surveyor in 1808 wrote about seeing "incredible" numbers of kangaroos and emus. The Indigenous people of Tasmania also had a close relationship with the emu. They used emu fat and oil for special ointments. Old records describe Aboriginal homes surrounded by emu feathers and bones. This shows how important the emu was to their lives.

How Humans Interacted with Emus

The Indigenous people often included the emu in their ceremonies. In 1834, people at Cape Grim danced and stretched their arms out. They were pretending to be emus with their long necks. Emus were also shown in Indigenous art. Drawings of emus were seen by Sir John and Lady Franklin during their journey in 1842. The place where they saw these drawings was later called Painters Plains.

The many places in Van Diemen's Land named after the emu also show how common they were. For example, a surveyor named Henry Hellyer saw emu footprints by a river. He then named it Emu River. Emu Bay got its name from that river. There are also places like Emu Bottom, Emu Valley, and Emu Hill. There was even an Emu Inn in Hobart as early as 1823.

Why the Tasmanian Emu Disappeared

By 1838, it was already hard to find Tasmanian emus. John Gould said you would need a month of searching in remote areas to see one. People started warning that the emu would soon be extinct. In 1826, a letter from Oyster Bay said, "they will soon be extinct." By 1832, some reported that emus were rarely seen in the midlands.

A newspaper in Hobart in 1832 worried about the emu's loss. It compared it to the Dodo, another extinct bird. The author suggested keeping some emus in a protected area. But these pleas did not save the bird. Many theories exist about why the Tasmanian emu vanished.

One big reason was hunting. Settlers hunted emus for food and because they saw them as a pest. Guns were used, but emus were fast. The introduction of domestic dogs changed hunting completely. Before Europeans arrived, Tasmania had no domestic dogs or dingos. The only other hunter of emus was the thylacine. Thylacines hunted by tiring out their prey. But domestic dogs, bred for speed, had a huge impact.

Another problem was habitat loss. Farmers would set fire to grasslands to clear land for farming. This destroyed the emus' homes. The subspecies likely became extinct around 1850. It's hard to know the exact date. Mainland emus were brought to Tasmania later. It's possible they even mixed with the last Tasmanian emus.

Fences also caused problems. On mainland Australia, emus often get hurt running into fences. This likely happened in Tasmania too. Emus cannot jump fences. They would walk along them trying to find an opening. Fences also meant less land for emus. Farmers were taking over and enclosing land. This limited the space and food the emus needed to live and reproduce.

Another idea is that invasive rats might have played a role. Some old documents mention Tasmanian Aboriginal people talking about rats eating "goanna" eggs. But Tasmania does not have goannas. This might have been a mistake in translation. "Gonanner" was an Aboriginal word for emu. So, rats might have eaten emu eggs, which would have been very bad for their numbers.

Museum Specimens

There are some Tasmanian emu specimens in museums around the world. In Australia, museums have emu eggs, bones, feathers, and skeletons. However, only a few Tasmanian emu skins are known to exist.

The Natural History Museum in London has some eggs and skins. In 1838, two skin specimens arrived at the British Museum. They were not properly listed until 1907. That's when an ornithologist named Dudley Le Souef found them. News spread to Australia, and the Tasmanian Museum asked for one skin back. But it was never returned.

During World War II, the museum was damaged. Many thought the emu skins were destroyed. But a year later, it was reported that they were safe. They had been moved to the museum in Tring, Hertfordshire. You can still find them there today.

There was thought to be a third specimen in Frankfurt, Germany. But it is now believed to be a mainland Australian emu that was brought to Tasmania. Another skin was given to the Saffron Walden Museum in 1833. Sadly, this emu specimen was likely thrown away in the 1960s when the museum reorganized its collections.

In 2018, the Austrian Natural History Museum in Vienna showed a stuffed Tasmanian emu.

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |