Technological unemployment facts for kids

Technological unemployment happens when people lose their jobs because new technology takes over tasks that humans used to do. It's a type of structural unemployment, which means jobs are lost for a long time, not just for a short period.

Think of it like this:

- Horses used to be important for transport and farm work, but cars and tractors replaced them.

- In the past, skilled weavers lost their jobs when machines could weave cloth much faster.

- During World War II, a machine called the bombe could break secret codes in hours, a job that would have taken humans thousands of years.

- Today, you might see self-service tills in stores, which means fewer cashiers are needed.

It's generally agreed that new technology can cause some job losses for a short time. But whether it leads to long-lasting unemployment has been a big debate for a long time.

Some people, called optimists, believe that even if technology causes job changes at first, new jobs will always appear later. Others, called pessimists, worry that new technologies could lead to fewer jobs overall in the long run.

The idea of "technological unemployment" became well-known in the 1930s when John Maynard Keynes, a famous economist, talked about it. He thought it was just a temporary problem. People have been discussing machines replacing human work since the time of Aristotle in ancient Greece!

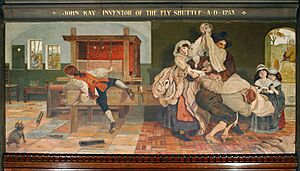

Before the 1700s, most people worried about technology taking jobs. But it wasn't a huge problem because there usually weren't many unemployed people. During the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain, machines became more common, and people worried more about job losses. However, some thinkers started to say that new inventions would actually create more jobs in the end. This idea became popular in the 1800s. People even created the term "Luddite fallacy" to describe the mistaken idea that technology would always cause lasting job problems.

Still, some economists have always warned about technology causing long-term unemployment. This debate became stronger in the 1930s and 1960s. More recently, with the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), the discussion has started again. Some experts, like Geoffrey Hinton, think AI might automate almost all jobs, meaning we might need a basic income for everyone. Others, like Daron Acemoglu, believe humans will still be needed for many tasks, working alongside AI. The World Bank said in 2019 that while automation changes jobs, technology also creates many new industries and jobs.

History of Job Changes

Ancient Times

The idea of technology affecting jobs has been around for a very long time, perhaps since the invention of the wheel! Ancient societies tried to help people who couldn't find work.

In ancient Greece, free workers sometimes lost jobs because of new tools or competition from slaves. To help, leaders like Pericles started public works projects, like building roads, to give people jobs.

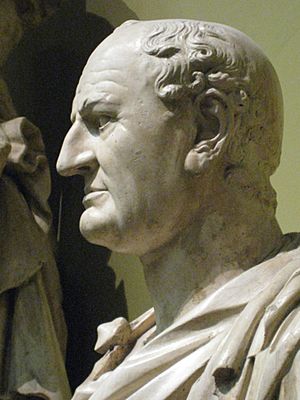

The Romans also gave out food to help the poor. Some Roman emperors even stopped new inventions if they thought it would cause too many people to lose their jobs. For example, Emperor Vespasian once refused a new way to transport heavy goods, saying his "poor hauliers" needed to earn a living. After the 2nd century AD, there weren't as many unemployed people in Europe for a long time.

Medieval and Renaissance Eras

During the Middle Ages and The Renaissance, many new technologies were adopted. After the Black Death plague, there were fewer workers in Europe. But later, in the 1400s, mass unemployment started to appear again in some parts of Europe. This was partly because more people were born, and partly because of changes in farming.

Because of the fear of losing jobs, new technologies were sometimes not welcomed. European leaders often sided with groups like Guilds (worker organizations) and banned new technologies. Sometimes, people who tried to promote new machines were even punished.

1500s to 1700s

In Great Britain, leaders started to be more open to new inventions earlier than in other parts of Europe. This helped Britain lead the Industrial Revolution. However, people still worried about jobs.

A famous story is about William Lee, who invented a knitting machine. He showed it to Queen Elizabeth I, but she refused to give him a patent (a special right to his invention). She said it would cause unemployment among textile workers and make them "beggars." He tried again with the next king, James I, but was refused for the same reason.

After the Glorious Revolution in the late 1600s, leaders became less concerned about workers losing jobs to new inventions. Some thinkers believed that new technology would actually help Britain compete better with other countries and create more jobs. By the 1700s, workers could no longer rely on leaders to protect their jobs from new machines. Sometimes, they would even break machines to protest. However, most leaders and thinkers started to believe that technological unemployment would not be a long-term problem.

1800s: Big Debates

The 1800s saw intense debates about technological unemployment, especially in Great Britain. Many new economic ideas were forming. Most economists believed that technology would not cause lasting unemployment.

However, some important economists, like David Ricardo, argued that new inventions could indeed cause long-term job losses. Other economists, like Jean-Baptiste Say, disagreed. Say argued that new machines would not reduce the amount of goods produced, and that new supply would create its own demand, meaning displaced workers would find new jobs.

Later, Karl Marx also joined the debate, arguing that technology would lead to serious job problems for workers. While his ideas gained many followers, mainstream economics still mostly believed that technology was good for jobs. By the 1870s, it became clear that new inventions were making everyone in Britain, including workers, more prosperous. So, worries about technology causing unemployment faded for a while.

1900s: Debates Return

For the first 20 years of the 1900s, mass unemployment wasn't a big issue. But in the 1920s, it became a problem again in Europe. Even in the U.S., urban unemployment started to rise in 1927, and farm workers had been losing jobs since the early 1920s due to new farm machines like the tractor.

The main debates about technological unemployment in the 1900s happened in the 1930s and 1960s. Both times, people started worrying when unemployment went up. And both times, the debates ended when wars (World War II and the Vietnam War) created many new jobs. Economists in the 1930s believed markets would fix any job losses, while in the 1960s, they thought government action could help.

After the 1970s, unemployment stayed high in many rich countries. Some economists, like Paul Samuelson, suggested this might be due to technology. Many books also warned about technological unemployment. However, for most of the 1900s, most economists and the public still believed that technology didn't cause long-term joblessness.

2000s: AI and New Concerns

The idea that technology doesn't cause long-term unemployment was strong in the early 2000s. But some books, like Robotic Nation and The Lights in the Tunnel, continued to raise concerns.

Since 2011, professors Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson from MIT have been important voices raising concerns about technology and jobs. They believe we need to learn to work with machines, not against them.

By 2013, worries about technological unemployment grew. Many studies predicted that automation would take over a lot of jobs in the coming years. Some evidence showed that in certain industries, jobs were falling even as production increased.

In 2014, Lawrence Summers, a former U.S. Treasury Secretary, said he no longer believed automation would always create new jobs. He noted that more job sectors were losing jobs than creating them. At the 2014 World Economic Forum in Davos, many leaders agreed that technology was leading to "jobless growth."

In 2015, Martin Ford won an award for his book Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future. In 2016, US President Barack Obama said that with the growth of AI, society might be discussing "unconditional free money for everyone" within 10 to 20 years. In 2019, AI expert Stuart J. Russell said that "nearly all current jobs will go away" in the long run, meaning we need big policy changes.

However, not everyone agrees. Many economists argue that long-term technological unemployment is unlikely. A 2014 survey of technology experts and economists found opinions split: 48% thought new tech would displace more jobs than it created by 2025, while 52% disagreed. Some argue that studies often overestimate job losses because they don't consider the new jobs technology will create.

Studies on Job Automation

Many studies have tried to guess how many jobs automation will take in the future.

- A 2013 study by Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne of Oxford Martin School estimated that 47% of US jobs were at high risk of automation. They found that jobs with clear, repeatable steps were most at risk, affecting both skilled and unskilled work.

- In 2014, a study found that 54% of jobs in the European Union were at risk.

- A 2016 study by the International Labour Organization found very high risks in some developing countries, like 77% of jobs in China and 69% in India.

- The US government's Council of Economic Advisers used the Oxford study data in 2016, estimating that 83% of jobs paying less than $20 per hour were at risk.

- A 2017 study by PricewaterhouseCoopers estimated that by the early 2030s, up to 38% of jobs in the US, 35% in Germany, 30% in the UK, and 21% in Japan were at high risk.

- A November 2017 report by McKinsey Global Institute estimated that 400 million to 800 million jobs could be lost worldwide by 2030 due to robots. They thought developed countries might lose more jobs because they have more money to invest in automation.

However, other studies have different findings:

- A 2015 study on industrial robots in 17 countries found no overall job reduction and a slight increase in wages.

- A 2016 OECD study found that only about 9% of jobs in surveyed countries were in danger of automation, though this varied by country.

- A 2017 study on Germany found that automation didn't cause total job losses. Instead, jobs shifted from the industrial sector to the service sector.

AI and the Future of Work

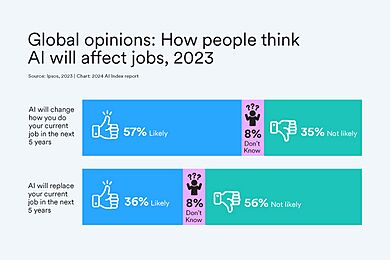

Since about 2017, there's been a new wave of concern about how artificial intelligence (AI) will affect jobs. Some experts warn that AI could cause job changes too fast for humans to keep up, leading to widespread unemployment. However, they also say that with the right actions from leaders and society, AI could be very good for workers.

Some researchers say it's hard to predict exactly what AI will do to jobs. One idea is that AI will mostly take over "middle-class" jobs, like some professional services. This might mean workers have to find new jobs that require different skills. However, many believe AI will mostly "complement people" (help them do their jobs better) rather than "replicate people" (replace them entirely).

Governments around the world are now creating plans for AI. Many believe that being a leader in AI will help their citizens get better jobs. For example, Finland offers a free online course on "The Elements of AI" to help people learn skills for the future. Some, like Oracle CEO Mark Hurd, predict AI will create more jobs because humans will be needed to manage AI systems.

Martin Ford argues that many routine jobs could be automated in the next few decades. He worries that many new jobs might not be suitable for people with average skills, even with retraining.

Key Ideas in the Debates

Long-Term Job Effects

Everyone agrees that new technology can cause temporary job losses and also create new jobs. The main debate is whether technology can cause a lasting drop in the total number of jobs.

Optimists believe in "compensation effects." This means that after some job losses, new jobs will always be created, making up for the ones lost. This optimistic view was common among economists for most of the 1800s and 1900s.

Pessimists argue that technological unemployment is a factor in "structural unemployment," which is a lasting level of joblessness. Since the 1980s, even optimists have accepted that structural unemployment has risen, but they often blame it on globalisation (companies moving jobs overseas) rather than technology. In the 2000s, especially since 2013, pessimists have increasingly warned that lasting technological unemployment is a growing threat worldwide.

Compensation Effects: How Jobs Come Back

Compensation effects are ways that new technology can create new jobs, making up for the jobs it might initially destroy. These ideas were first explained in the 1820s. Karl Marx later criticized them, saying they weren't guaranteed to work. The debate over how well these effects work is still central to the discussion.

Here are some ways new jobs can be created:

- New Machines: Jobs are created to build the new machines and equipment.

- New Investments: When companies save money and make more profit from new technology, they can invest that money, which creates new jobs.

- Wage Changes: If unemployment happens, wages might go down, making it cheaper to hire workers. Or, if workers become more productive, their wages might go up, leading to more spending and new jobs.

- Lower Prices: New technology can make goods cheaper. This means people buy more, which increases demand and creates more jobs. Cheaper goods also mean workers' money goes further.

- New Products: Sometimes, new inventions directly create entirely new industries and jobs (like the internet creating web designers).

Many economists who worry about technological unemployment agree that these "compensation effects" worked well in the 1800s and 1900s. However, they argue that with computers, these effects are less powerful. Early machines replaced muscle power, but still needed many human operators. Now, computers can replace brain power too, meaning less demand for human labor even as productivity rises.

The "Luddite Fallacy"

The term "Luddite fallacy" is used by people who believe that worries about long-term technological unemployment are wrong. They think that those who worry don't understand how compensation effects work. They expect that technology will not cause long-term job problems and will eventually raise wages for everyone by making society richer. The term comes from the Luddites, a group in the early 1800s who destroyed textile machines because they feared losing their jobs.

For most of the 1900s and early 2000s, most economists believed that worrying about long-term technological unemployment was indeed a "fallacy." However, more recently, there's been more support for the idea that the benefits of automation are not shared equally among everyone.

There are two main ideas about why long-term job problems could happen: 1. Limited Work: This idea, sometimes linked to the Luddites, suggests there's only a certain amount of work available. If machines do it, there's none left for humans. Economists call this the "lump of labour fallacy" and argue it's not true. 2. Machines Do "Easy" Work: This view says there's an endless amount of work, but machines are getting better at doing the "easy" work that doesn't need much skill or deep thought. As technology improves, more and more work becomes "easy" for machines, and the remaining "hard" work might be too complex for most people.

Many modern experts who worry about long-term unemployment support this second view.

Skills and Technology

Many people think that new technology mostly hurts low-skilled workers, while helping skilled workers. This might have been true for much of the 1900s. However, in the 1800s, new inventions often replaced highly skilled craftspeople, and sometimes helped low-skilled workers.

Today, while some low-skilled jobs are being automated, other low-skilled jobs are hard for robots to do. At the same time, some "white-collar" jobs that require medium skills are increasingly being done by computer programs.

Some studies show that industrial robots boost pay for highly skilled workers but have a negative impact on low to medium-skilled workers. Other reports predict that in the next ten years, automation will most affect low-skilled jobs.

Some experts, like Geoffrey Colvin, argue that it's hard to predict what jobs computers will never be able to do. Instead, we should think about jobs where humans will always be needed for important decisions (like judges or CEOs) or where human connection is essential (like care work).

However, others believe even skilled human jobs could become unnecessary. Some predict that nearly half of all jobs could be automated. For example, in 2012, Vinod Khosla, co-founder of Sun Microsystems, predicted that 80% of doctors' jobs could be lost to automated medical software in two decades.

Solutions to Job Changes

Preventing Job Losses

Stopping New Inventions

Historically, new inventions were sometimes banned to protect jobs. However, in modern economics, this is almost never considered a solution, especially for rich countries. Most people agree that new inventions are good for society overall.

Gandhi suggested slowing down the use of labor-saving machines until unemployment was solved, but this idea was mostly rejected in India. China under Mao did try to slow down new inventions in the 1900s to avoid job losses.

Shorter Working Hours

In 1870, the average American worker worked about 75 hours a week. By World War II, this had fallen to about 42 hours. This was partly a choice to have more free time as technology made workers more productive.

Some economists have suggested reducing working hours even more to share available work and reduce unemployment. For example, Google's co-founder, Larry Page, suggested a four-day workweek in 2014. However, once people work around 40 hours a week, they are less eager to work even fewer hours, partly to avoid losing income and partly because many enjoy their work.

Public Works Programs

Governments have often used public works programs (like building roads or bridges) to create jobs directly. Even economists who support free markets have sometimes suggested this as a solution to technological unemployment. Some argue that public works and guaranteed jobs in the public sector are better than just giving people money, because they provide people with a sense of purpose and social recognition.

Education and Training

Improving access to good education and skills training for adults is a solution that almost everyone agrees on. It's especially popular with businesses. However, some experts argue that education alone won't solve technological unemployment, because not everyone can become highly skilled, and many medium-skilled jobs are also at risk.

Living with Technological Unemployment

Welfare Payments

Giving financial aid to people who are unemployed has often been accepted as a solution, even by those who are optimistic about technology's long-term effects on jobs. Historically, welfare programs tend to last longer than other job-creation solutions. Even early economists who believed in compensation effects still supported government aid for those affected by technology, because they knew that markets don't adjust instantly.

Basic Income

Some experts argue that traditional welfare payments might not be enough for the future challenges of technological unemployment. They suggest a basic income instead. This is a regular payment given to everyone, regardless of whether they work. People like Martin Ford, Elon Musk, and Andrew Yang support this idea.

Some worry that a basic income might make people not want to work. However, evidence from past trials in places like India and Canada suggests that it doesn't stop people from working and can even encourage small businesses. Another challenge is how to pay for it. Ideas like a "wage recapture tax" have been suggested, but funding a generous basic income is still a big question.

Sharing Ownership of Technology

Another idea is to spread the ownership of robots and other productive technologies more widely. This means more people would own a part of the companies that use these technologies, so they would share in the profits. People like James S. Albus and Richard B. Freeman have suggested this.

Jaron Lanier has a similar idea: people could receive small payments for the data they create by using the internet.

Structural Changes for a "Post-Scarcity" Economy

Some groups, like The Zeitgeist Movement, propose big changes towards a "post-scarcity economy." In this future, people are "freed" from boring, automatable jobs instead of "losing" them. They believe all jobs would either be automated, removed if they don't add real value (like some advertising), or done voluntarily for social good. This would give people more free time for creativity, invention, and community activities, and reduce stress.

Other Ideas

Some economists suggest a mix of solutions. Larry Summers has advised a package of measures, including:

- Making it harder for very rich people to avoid taxes.

- Stronger rules against monopolies (when one company controls too much).

- Less protection for intellectual property (like patents) to encourage more competition.

- More profit-sharing schemes for workers.

- Better training for young people and retraining for displaced workers.

- More public and private investment in things like energy and transportation.

Michael Spence believes that adapting to technology's impact will require big changes in how we think, our policies, and our investments, especially in human capital (people's skills and knowledge).

Images for kids

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |