Timothy Hackworth facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Timothy Hackworth

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 22 December 1786 Wylam, Northumberland, England

|

| Died | 7 July 1850 (aged 63) |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Engineering career | |

| Discipline | Locomotive engineer |

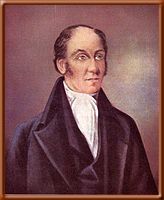

Timothy Hackworth (born December 22, 1786 – died July 7, 1850) was an important English engineer. He helped build early steam locomotives. He lived in Shildon, England. Hackworth was the first person in charge of locomotives for the Stockton and Darlington Railway. This was one of the world's first public railways.

Contents

Early Life and First Locomotives

Timothy Hackworth was born in Wylam in 1786. Another famous railway pioneer, George Stephenson, was born in the same village five years earlier. Timothy's father, John Hackworth, was a skilled blacksmith and boiler maker at Wylam Colliery (a coal mine). When his father died in 1804, Timothy took over his job in 1810.

The mine owner, Christopher Blackett, wanted to use steam engines to move coal on the mine's short 5-mile (8 km) railway. Blackett formed a team with William Hedley, Jonathan Forster, and Timothy Hackworth to figure this out. First, in 1808, they replaced the wooden tracks with stronger cast iron ones.

In 1811, the team studied how well smooth wheels gripped the tracks. They even built a simple, hand-powered cart to test this. That same year, they built a single-cylinder steam engine. It was based on ideas from Richard Trevithick, another early inventor. This engine worked for a few months, but not very well.

Building the Wylam Dillys

A new "dilly" (the name for locomotives at Wylam) was built in 1812. But the new cast iron tracks were not strong enough for its weight. So, the next dilly, built in 1813, had two four-wheeled "power bogies." These spread out the weight better. The first dilly was also changed to this design.

Around 1830, the Wylam line got even stronger wrought iron tracks. The two locomotives were then changed back to a 4-wheel design. They kept working until the line closed in 1862. One of these engines, called Puffing Billy, is now at the Science Museum in London. The second, Wylam Dilly, is in the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh.

William Hedley often gets credit for designing these locomotives. However, there is strong evidence that it was a team effort. Christopher Blackett was the main driver, and Timothy Hackworth played a very important engineering role. Hackworth was also responsible for keeping the engines running and making them better. He left Wylam in 1816 because of disagreements, partly due to his religious beliefs. He soon found a similar job at Walbottle Colliery.

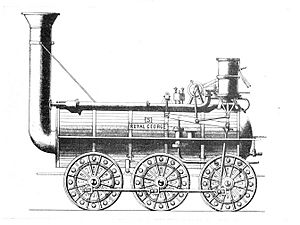

The Royal George Locomotive

In 1824, Hackworth worked for a short time at Robert Stephenson and Company. This was while Robert Stephenson was away in South America. George Stephenson, Robert's father, was busy planning new railways. Hackworth returned to Walbottle at the end of that year.

Then, in May 1825, George Stephenson suggested Hackworth for a new job. Hackworth became the locomotive superintendent for the Stockton and Darlington Railway. He held this important position until 1840.

Hackworth helped develop the first Stephenson locomotive for the Stockton and Darlington Railway. This engine, first called Active, is now known as Locomotion No. 1. It was delivered just before the railway opened on September 27, 1825. Three more engines like it were delivered soon after. These early engines had many problems. It was Hackworth's hard work that made them usable.

Improving Steam Engines

Hackworth's efforts led to the creation of the Royal George in 1827. This was an early 0-6-0 locomotive. It had many new features, including a properly designed blastpipe. A blastpipe uses the exhaust steam from the engine to make the fire burn hotter. This creates more steam, making the engine more powerful.

Hackworth is usually given credit for inventing this important device. From 1830 onwards, the Stephensons used the blastpipe in their improved Rocket and all their new engines. Hackworth was likely the first engineer to fully understand how the blastpipe helped balance steam production and use in a locomotive. He paid close attention to its size, position, and alignment.

Sans Pareil and the Rainhill Trials

In 1829, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was being built. This was the world's first "Inter-City" railway. It needed locomotives that could carry both passengers and goods quickly. All engines built before this were for slow freight.

There was a lot of debate about what kind of power to use. George Stephenson, the railway's engineer, strongly supported steam engines. He asked Timothy Hackworth for a report. Hackworth confirmed he was having problems with the Stockton and Darlington engines but was hopeful he could fix them.

To decide on the best locomotive, the railway directors held a competition. These were the Rainhill Trials. Three serious teams entered. Hackworth, with limited money, entered his 0-4-0 locomotive, Sans Pareil. His engine was officially too heavy. But it was still allowed to compete. Unfortunately, a problem with its cylinder caused steam leaks, and it had to stop early.

Stephenson's Rocket won the trials. It was the only locomotive that finished the course and followed all the rules. However, none of the engines truly met all the railway's needs. Hackworth stayed after the event and repaired Sans Pareil. He showed that it could do more than required. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway bought the locomotive. It later worked on the Bolton and Leigh Railway until 1844. Sans Pareil was a strong competitor, largely thanks to its well-designed blastpipe.

The Rainhill Trials were a very important event. During the eight days, many changes were made to the three main competing engines. Hackworth worked tirelessly and fairly during this time. After these trials, locomotive design and performance improved very quickly.

Later Engineering Projects

Besides his work for the Stockton and Darlington Railway, Hackworth also started his own business. His son, John Wesley Hackworth, worked with him. This business made many different types of machines.

In 1836, he built the first locomotive to run in Russia at his Shildon factory. His son was in charge of delivering it safely and testing it. Also, in 1838, the Samson was built for the Albion Mines Railway in Nova Scotia, Canada. It was one of the first engines to run in Canada.

One of his apprentices from 1833, Daniel Adamson, later improved Hackworth's boiler designs. Adamson became a successful manufacturer and helped start the Manchester Ship Canal.

Timothy Hackworth's last new locomotive design was the Sans Pareil II in 1849. This was a very advanced 2-2-2 engine. It was very good at saving fuel and pulling heavy loads. Hackworth was so pleased that he publicly challenged Robert Stephenson to a trial against his latest engine. But nothing more came of this challenge.

Family Life

Hackworth had three sons and six daughters. His oldest son, John Wesley Hackworth (1820–1891), continued the family business after his father's death. John Wesley Hackworth also invented the Hackworth valve gear in 1859, which was a way to control steam engines.

Legacy and Recognition

Today, a school in his hometown of Shildon is named after Timothy Hackworth. Students there learn about his life and work every year. His old home was also turned into a museum. It has been updated, and a part of the National Railway Museum has been built nearby.

The 1839 Hackworth locomotive Samson is kept in Canada at the Nova Scotia Museum of Industry in Stellarton, Nova Scotia. Hackworth Park in Shildon was named in his honor. Timothy Hackworth Drive in Darlington also carries his name.

See also

- 1786 in rail transport

- Locomotives of the Stockton and Darlington Railway

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |