Tutinama facts for kids

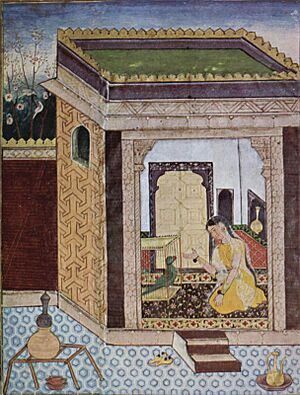

Parrot addressing Khojasta

|

|

| Author | Nakhshabi |

|---|---|

| Country | India |

| Language | Persian |

| Genre | Fables |

|

Publication date

|

14th century |

The Tutinama (which means "Tales of a Parrot" in Persian) is a collection of 52 stories from the 14th century. These stories were written in the Persian language. The Tutinama is very famous because of its many beautiful illustrated copies. One special version has 250 tiny paintings and was ordered by the Mughal Emperor, Akbar, in the 1550s.

The Persian stories were based on an older collection called "Seventy Tales of the Parrot." This older book was written in Sanskrit around the 12th century. In India, parrots are often seen as great storytellers in books because people believe they can talk.

The stories in the Tutinama are told by a parrot, night after night, for 52 nights. They are moral stories, meaning they teach lessons. The parrot tells these tales to convince his owner, a woman named Khojasta, not to leave her home while her husband is away. Khojasta often wants to go out to meet someone, but the clever parrot always stops her by telling a fascinating story.

Many illustrated copies of the Tutinama still exist today. The most famous one was made for Emperor Akbar. It took five years to create, starting in 1556 when he became emperor. Two Persian artists, Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd al-Samad, worked on it in the royal workshop. Most of this famous copy is now in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Another version made for Akbar is spread across different museums, but the largest part is in the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin. This copy is thought to be from around 1580.

Contents

The Storyteller and His Tales

The stories in the Tutinama were written by Ziya'al-Din Nakhshabi, also known as Nakhshabi. He was a doctor and a Sufi saint from Iran who moved to Badayun, Uttar Pradesh in India, during the 14th century. He wrote in the Persian language. Nakhshabi translated or edited an old Sanskrit version of these stories into Persian around 1335 AD.

People believe that this small book of short, moral stories helped shape Akbar when he was young. It's also thought that because Akbar had a large group of women in his palace (sisters, wives, and servants), these moral stories were created to guide women's behavior.

Akbar's First Illustrated Version

The artists Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd al-Samad were first invited by Humayun (Akbar's father) around 1530–40. They taught painting to Humayun and his son Akbar. The artists first came to Kabul with Humayun when he was in exile. Later, they moved to Delhi when he won back his empire. The artists then went to Fatehpur Sikri with Emperor Akbar. There, a huge workshop of artists worked on creating miniature paintings.

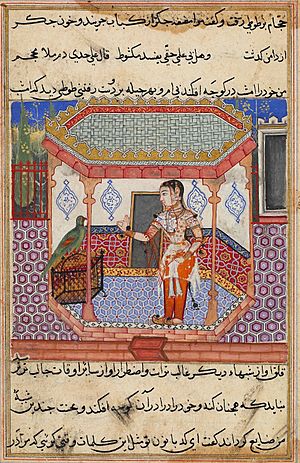

This style of art became known as Mughal painting. It grew very popular during Akbar's rule from 1556 to 1605, when the Mughal empire was at its strongest. Akbar personally supported these miniature paintings. He not only used Iranian artists but also many Indian artists who knew local styles of miniature painting. This led to a unique mix of Indian, Persian, and Islamic art styles.

Most of these paintings are now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, and some are in the British Library. The Tutinama paintings were the first step for many other beautiful Mughal miniature painting collections. These include the Hamzanama (Adventures of Amir Hamza), Akbarnama (Book of Akbar), and Jahangirnama (the autobiography of Emperor Jahangir). These were made during the reigns of later Mughal rulers (from the 16th to 19th centuries). They also showed influences from Indian, Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist art.

Mughal paintings often showed portraits of emperors and queens, court scenes, hunting, special events, battles, and royal activities. This style of miniature painting was also adopted by Rajput and Malwa rulers. One painting in the Tutinama is believed to be the earliest known portrait of Akbar as a king.

What the Stories Are About

The main storyteller in the 52 tales of Tutinama is a parrot. He tells stories to his owner, a woman named Khojasta. He does this to stop her from doing anything her husband would not approve of while he is away on a business trip. Khojasta's husband, a merchant named Maimunis, left her with a mynah bird and a parrot.

The wife kills the mynah bird because it advised her not to do anything wrong. The parrot, seeing how serious the situation was, decided to try a different way. He started telling fascinating stories over 52 nights. The stories are told every night to keep Khojasta entertained and stop her from leaving the house.

An Example Story

One particular story the parrot tells to keep his mistress's attention is shown in paintings 35 to 37 of the illustrated Tutinama. This happens when Khojasta is about to leave the house at night.

The parrot tells a story about a Brahmin boy who falls in love with a princess. This was seen as a very difficult situation. But a magician, who was a friend of the Brahmin, helps him. The magician gives him magic beads that turn him into a beautiful woman. This allows him to enter the palace and be with the princess he loves. The magician also helps his friend meet the king's daughter by telling the King that the girl was his daughter-in-law.

Once inside the palace, the Brahmin tells the princess who he really is. But then, a new twist happens! The King's son sees the beautiful girl (the Brahmin in disguise) bathing in a pond and falls in love with her. To avoid being discovered, the Brahmin runs away with the King's daughter. The magician then appears before the King, asking for his "daughter-in-law" back. But the King realizes what has happened to the two missing girls. He gives the magician many rich gifts. The magician then gives these gifts to his Brahmin friend and his wife so they can live a happy life.

The parrot finishes the story as day breaks. He advises Khojasta that she should also have everything good in her life, including her husband.

Art Style of the Paintings

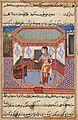

The text of the Tutinama was written in a beautiful writing style called Nasta'liq calligraphy. Each painting in the various copies of the Tutinama focuses on one part or event from the stories. The clear and direct way things are shown in the paintings is thought to be influenced by older, pre-Mughal art.

Some Tutinama paintings are similar to illustrations found in Malwa manuscripts from 1439 AD. However, the Tutinama paintings show a distinct level of perfection. The difference is in the lovely colors used in Tutinama paintings, which make them rich and high-quality.

The popular dance style of Kathak, which combines Indian and Persian forms, is shown in the paintings of the Tutinama, the Akbarnama, and the Tarrikh-e-Khandan-e-Timuria. In these paintings, men and women are shown wearing long, flowing robes and tall, pointed hats while standing. Some paintings even show two different groups of dancers. It is believed that 350 dancers were brought to Akbar's court from Iran. These dancers likely represented ancient Iranian dance traditions. Over time, Persian and Indian people blended their cultures, which helped create the Kathak dance style we see in India today.

Images for kids

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |