Walam Olum facts for kids

The Walam Olum (also called Walum Olum) is a story that was said to be the history of the Lenape (Delaware) Native American tribe. Its name means "Red Record" or "Red Score." This document has been very controversial. Since it was first published in the 1830s, people have argued if it is real or fake. A scientist named Constantine Samuel Rafinesque published it. Later studies in the 1980s and 1990s found strong proof that the Walam Olum is not a real historical record. Many experts now believe it is a hoax.

Contents

What is the Walam Olum?

In 1836, Constantine Samuel Rafinesque published what he said was a full English translation of the Walam Olum. He also included a part of it in the Lenape language.

The Walam Olum tells a story that includes:

- A creation myth, explaining how the world began.

- A deluge myth, about a great flood.

- Stories of different migrations (journeys).

Rafinesque and others thought these migrations started in Asia. The Walam Olum suggested a journey across the Bering Strait happened about 3,600 years ago. The text also listed many chiefs' names. This list seemed to show a timeline for the story. Rafinesque claimed these chiefs appeared as early as 1600 BCE.

The Story in Short

The story begins with the universe being formed. The Earth is shaped, and the first people are created by the Great Manitou. As the Great Manitou creates good creatures, an evil manitou creates bad ones, like flies.

At first, everything is peaceful. But then, an evil being brings sadness, sickness, and death. A giant snake attacks the people. It drives them from their homes and floods the land. The snake also creates monsters in the water.

But the Creator helps the people. He makes a giant turtle. The people who survived the flood ride on this turtle. They pray for the water to go down. When land appears again, they are in a cold, snowy place. So, they learn to build houses and hunt. They start exploring to find warmer lands.

Eventually, they decide to go east. They travel from the land of the Turtle to the land of the Snake. They walk across a frozen ocean. They first reach a land with spruce trees.

After some time (and new chiefs are named), they spread into nearby areas. Many generations pass. The story briefly describes each chief. A large part of the nation decides to attack the Talegawi people. They get help from the northern Talamatan.

The attack succeeds, but the Talamatan later become enemies. However, they are soon defeated. A long time of peace and growth follows. The people slowly expand into rich eastern lands. They finally reach another sea. After many more generations, the first white men arrive in ships.

This is where the main story ends. Rafinesque did publish a small extra part. It continued the story up to his own time. This extra part said the original Walam Olum was written by someone named Lekhibit.

Where Did It Come From?

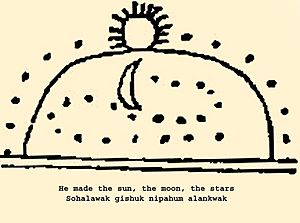

Rafinesque said the original story was written using pictures. These pictures were on birch bark, or on wooden tablets or sticks. He explained that "Olum" means a record, like a notched stick or engraved wood.

He claimed that a "Dr. Ward of Indiana" got these materials in 1820. Dr. Ward supposedly received them from a Lenape patient. Rafinesque said Dr. Ward later gave them to him.

Rafinesque also said he got the Lenape language verses from a different source in 1822. After he published his translation, Rafinesque claimed he lost the original plaques.

When Rafinesque wrote about the Lenape language in 1834, he didn't mention the Walam Olum. He added a section about it two months later. This was after he got a list of real Lenape names from another person.

Rafinesque's translation of 183 verses is less than 3,000 words long. In his notes, he put the pictures next to the Lenape verses. These notes are now at the University of Pennsylvania. They have been made digital so people can see them.

There is no proof, other than Rafinesque's own words, that the original sticks ever existed. Scholars only have his published work to study.

Archaeology in the 20th century showed that Native Americans had used birch bark scrolls for over 200 years. In 1965, an archaeologist found carved birch bark pieces in Ontario. These pieces had animal, bird, and human figures. Some looked like scrolls used by the Mide Society of the Ojibwe. One scroll was dated to about 1560 CE.

The Walam Olum in the 1800s

For many years, the Walam Olum was seen as a true historical account. This was true even though some people doubted it. Historians, anthropologists, and archaeologists often accepted it.

E. G. Squier, a famous archaeologist, republished the text in 1849. He believed it was real. He showed the manuscript to a well-educated Native American chief, George Copway. Copway said it was "authentic" and that the translation was faithful. However, later experts noted that Copway was not an expert on Lenape traditions.

In 1885, Daniel G. Brinton, a well-known ethnographer, published a new translation. He said that the pictures seemed to match his corrected translations, not Rafinesque's. Brinton thought this proved that Rafinesque got the text and pictures from someone else, which made them seem more real.

The Walam Olum in the 1900s

In the 1930s, Erminie Voegelin tried to find similar stories in other Lenape sources. The results were not clear. Doubts about the text's truth began to grow.

In 1952, archaeologist James Bennett Griffin said he did not trust the Walam Olum. Historian William A. Hunter also thought it was a hoax. In 1954, archaeologist John G. Witthoft found mistakes in the language. He also noticed that some words matched 19th-century Lenape-English word lists too perfectly. He believed Rafinesque created the story from Lenape texts that were already printed.

In 1954, a group of scholars published another translation. They said the "Red Score" was important for studying Native American culture. But a reviewer noted that they couldn't find Dr. Ward. He concluded that the document's origins were "clouded."

Later, in the 1980s, experts had enough information to completely reject the Walam Olum. Herbert C. Kraft, a Lenape expert, had long suspected it was fake. He said it didn't match archaeological findings about Lenape migrations. Also, a survey in 1985 asked Lenape elders about the story. They had never heard of it. They found the text confusing and hard to understand.

In 1991, Steven Williams said the Walam Olum was like other famous archaeological frauds. He said that even if other real picture documents exist, they don't make up for the problems with the Walam Olum text and its history.

The Walam Olum Since 1994

In 1994, David M. Oestreicher provided strong proof that the Walam Olum was a hoax. He looked at Rafinesque's original notes. He found many Lenape words that were crossed out. These were replaced with words that better matched Rafinesque's English translation. This suggested that Rafinesque was translating from English to Lenape, not the other way around.

Oestreicher found that the Walam Olum was not a real historical record. He believed it was made by someone who knew only a little about the Lenape language. Oestreicher argued that Rafinesque created the language text from other published sources. He also said the "Lenape" pictures were mixed from Egyptian, Chinese, and Mayan sources.

Another expert agreed. He said the pictures were not like those found in the Lenape homeland. David Oestreicher believed the stories were a mix of ideas from many different cultures around the world. Some think Rafinesque created the Walam Olum to win a prize. He also wanted to prove his ideas about how people first came to America.

Later, Joe Napora, who had translated the text, admitted it was a hoax. He was upset that the sources he trusted had not investigated the document properly.

Many traditional Lenape people believe they have always lived in their homeland. This area includes New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York. The Delaware Tribe of Indians first supported the document. But they withdrew their support in 1997 after seeing the evidence. The Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania believes they have been in the area for 10,000 years.

Even though it is likely a fake, the Walam Olum still has a very important and controversial place in the history of American anthropology.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |