War hysteria preceding the Mountain Meadows Massacre facts for kids

The Mountain Meadows Massacre was a terrible event that happened in Utah Territory in September 1857. It was a time when tensions were very high between the United States Army and the Mormon settlers. This period is known as the Utah War.

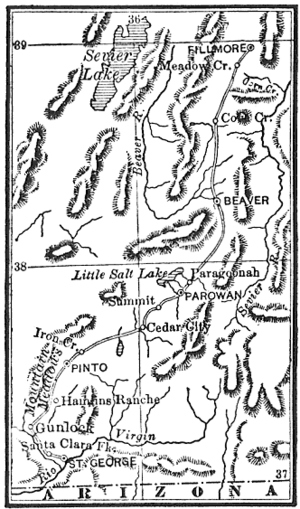

In the summer of 1857, many Mormons felt very worried, expecting a big invasion. From July to September 1857, Mormon leaders told their people to get ready for a long "siege" (a military blockade) that their leader, Brigham Young, had predicted. Mormons were told to save their grain and not sell it to travelers for animal food. As some distant Mormon communities moved closer, places like Parowan and Cedar City became isolated. Brigham Young also encouraged Native American tribes to help fight the "Americans" and to take cattle from traveling groups.

In August 1857, George A. Smith, a Mormon leader from Parowan, traveled through southern Utah. He told Mormons to save grain. Experts believe Smith's speeches made people more fearful. This fear likely played a part in the decision to attack a group of travelers called the Baker–Fancher party near Mountain Meadows, Utah. Smith met with people who later took part in the massacre, including William H. Dame, Isaac C. Haight, and John D. Lee. He noticed that the local militia (a group of citizens trained as soldiers) was ready to fight. Some even wanted to "take vengeance" for past troubles. On his way back to Salt Lake City, Smith camped near the Baker–Fancher party. Jacob Hamblin suggested the Fanchers rest their cattle at Mountain Meadows. Some people with Smith spread rumors that the Fanchers had poisoned a well and a dead ox to harm Native Americans. These rumors reached Cedar City before the Fanchers did. However, most witnesses said the Fanchers were generally peaceful travelers.

Some Native American chiefs from the Mountain Meadows area were with Smith's group. When Smith returned to Salt Lake, Brigham Young met with these chiefs on September 1, 1857. He encouraged them to fight against the "Americans." The chiefs were reportedly not eager to fight. Some experts think these leaders returned to Mountain Meadows and were part of the massacre, but it's not certain if they had enough time.

Contents

The Baker–Fancher Party: Who Were They?

In early 1857, several groups of travelers from Arkansas began their journey to California. They joined together along the way and became known as the Baker–Fancher party. This group had a good amount of money and planned to buy more supplies in Salt Lake City, which was common for wagon trains back then. The party reached Salt Lake City with about 120 people. In Salt Lake, there was an unproven rumor that the widow of a respected Mormon leader, Parley P. Pratt, thought one of the travelers had been involved in her husband's murder.

For ten years before the Fanchers arrived, Utah Territory was led by Brigham Young. He had a vision of a "Kingdom of God." Young set up communities along the California and Old Spanish Trails. Mormon officials governed these areas. Two of the southernmost communities were Parowan and Cedar City. They were led by Stake Presidents William H. Dame and Isaac C. Haight. Haight and Dame were also important military leaders of the Nauvoo Legion, which was the Mormon militia. Just before the massacre, during a time called the Mormon Reformation, Mormon teachings were very strong. The religion had faced a lot of unfair treatment in the past. Many faithful Mormons had made promises to seek revenge on those who had killed their leaders, like founder Joseph Smith and, more recently, Parley P. Pratt, who was killed in April 1857 in Arkansas.

The Utah War: A Time of Fear

In July 1857, while the Baker–Fancher party was traveling to Utah Territory, Mormons started hearing rumors. They heard that the United States government was sending an army to invade the territory. The goal was to remove its religious government. For almost ten years, relations between Utah and the U.S. government had been difficult. This was due to issues like polygamy (having more than one spouse) and the role of Mormon groups versus federal ones. By July 1857, a new governor, Alfred Cumming, had been chosen. Also, about a fourth of the entire U.S. army, around 2,500 soldiers, were already on their way.

As news of the approaching army spread, many Mormons saw it as a huge threat to their very existence. Leaders of the First Presidency (a top leadership group) described the conflict as a battle between good and evil. Some Mormons in southern Utah believed the invasion was the start of a major religious event. The common belief was that the U.S. Army planned to wipe out the Mormons. To prepare for a seven-year siege, Mormon leaders sped up their plan to store grain. Mormons were told to sell their clothes to buy as much grain as possible. They were also told not to use grain for animal food or sell it to travelers for that purpose.

Brigham Young was defiant against the United States. He warned "mobocrats" (people who cause trouble), especially those who had treated Mormons badly in the past. He said if such people entered the territory, they would face a "Vigilance Committee" and the "Danites" (groups associated with protecting Mormon interests). However, Young also said that Mormons should not rob "innocent" traveling groups. He wanted to make sure that "the good and honest may be able to pass from the Eastern States to California...in peace."

Young ordered distant Mormon communities to move closer. This included settlements in San Bernardino (California), Las Vegas (Nevada), Carson Valley (Nevada), and Fort Bridger (Wyoming). After this, the furthest Mormon outposts were Cedar City (led by Stake President-Major Isaac C. Haight) and Parowan (led by Stake President-Colonel William H. Dame). These two small fortress-villages were near Mountain Meadows, where the massacre happened. These communities were almost 300 miles from Salt Lake City. It took three days to reach them by horseback, with messengers changing horses along the way. Mormons in the Cedar City area were meant to be the first defense against an attack from the south. The word from Mormon headquarters was that the approaching U.S. Army had orders to kill every believing Mormon. They also heard the troops were coming directly from Missouri.

On August 5, 1857, Brigham Young declared martial law. This meant military rule was in effect. All borders were to be closed to further travel through Utah by emigrants. Young also made it illegal to travel through Utah without a permit. However, the Baker–Fancher train was not given a safe conduct pass. The travelers would not have known about Young's order, as it was only made public on September 15, 1857.

Traveling groups from the east offered a chance for Mormons to trade or sell food and other supplies. Until the Utah War, most interactions were friendly. The Baker–Fancher train met residents who were following Young's order to save supplies for the expected war. Mormons were told not to sell any food to the "enemy," which is how the traveling group was labeled.

George A. Smith's Journey Through Southern Utah

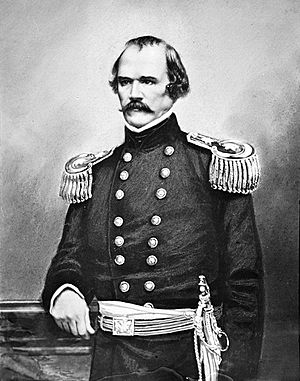

On August 3, 1857, Mormon leader George A. Smith left Salt Lake City to visit the southern Utah communities. He arrived at Parowan on August 8, 1857. On August 15, 1857, he began a tour of Stake President-Colonel W. H. Dame's military area. During this tour, Smith gave speeches about military readiness. He advised Mormons to be ready to "touch fire to their homes" (burn them down) and hide in the mountains. He told them to "defend their country to the very last." Smith also told Mormons to save grain and not sell it to travelers for animal food. Experts say that Smith's tour, speeches, and actions made the communities more fearful and tense. This fear likely influenced the decision to attack the Baker–Fancher traveling group near Mountain Meadows.

John D. Lee went with Smith for part of this tour. During this time, Smith spoke to a group of Native Americans in Santa Clara. He told them that "the Americans" were coming with a large army. He said they were a threat to both the Native Americans and the Mormons. Lee later said that while riding in a wagon, he warned Smith that the Native Americans might attack traveling groups. He also said that Mormons wanted to get revenge for their leaders. According to Lee, Smith seemed pleased and said he had talked about the same thing with Major Haight.

Major Isaac C. Haight, the leader of Cedar City, met with Smith again on August 21. Haight told Smith he had heard reports that 600 soldiers were already coming toward Cedar City from the East. He said if the rumors were true, he would have to act without waiting for orders from Salt Lake City. Smith agreed and "admired his grit" (his courage). Smith later said he felt uneasy, perhaps because of his "extreme timidity." He felt this because some militia members were eager for their "enemies" to come. They wanted a chance to "fight and take vengeance for the cruelties that had been inflicted upon us in the States," such as the Haun's Mill massacre.

LDS Church Apostle.

Leader of Cedar City and second in command

On his way back to Salt Lake City, Smith was joined by Jacob Hamblin of Santa Clara. Hamblin was a new Mormon missionary to the Native Americans in the area. He also ran a farm for Native Americans near Mountain Meadows, which was funded by the government.

Several Native American chiefs from southern Utah Territory also traveled north with Smith's group. On August 25, 1857, Smith's group camped next to the Baker–Fancher party at Corn Creek (now Kanosh). The Fanchers were traveling in the opposite direction. Smith later said he did not know about the Baker–Fancher party before meeting them on the trail. When the Baker–Fancher party asked about places to stop for water and grazing, Jacob Hamblin told them about Mountain Meadows. This was near his home and the Native American farm, and it was a regular stop on the Old Spanish Trail.

Some people with Smith later said that during their camp, they saw the Baker–Fancher party poison a spring and a dead ox. They believed the Fanchers hoped Native Americans would be poisoned. Silas S. Smith, George A. Smith's cousin, said that the Baker–Fancher party suspiciously asked if Native Americans would eat a dead ox. Although the poisoning story supported the Mormon idea that Native Americans had been poisoned and then carried out a massacre on their own, modern historians generally believe the rumors about the poisoned ox and spring were false. Nevertheless, the poisoning story reached the Fanchers' next stops as they traveled south.

Interactions on the Road to Mountain Meadows

Mormons saw the Baker–Fancher travelers as "aliens" (outsiders). This was because Brigham Young had ordered that no one could travel through Utah without a special pass, which the Baker–Fancher party did not have. However, Captains Baker and Fancher might not have known about Young's martial law order, as it was not made public until September 15, 1857.

The Fancher and Duke parties (from Arkansas and Missouri) had helped each other on their journey west. Some locals believed that the Fancher party was joined by eleven members of a Missouri militia called the "Wildcats." (But there is debate about whether these miners and plainsmen stayed with the slow-moving Baker–Fancher party after leaving Salt Lake City, or if they even existed.)

Meanwhile, the Mormons that the Baker–Fancher train met were following Young's order to save supplies for the expected war. They refused to trade with the Fanchers. This caused more problems. Also, a "range war" (conflict over grazing land) was expected to happen between local people and any travelers with large herds of cattle. Indeed, both the Fancher and Duke parties' cattle would compete with local animals for grass. Sometimes, they would even break through the Mormon settlers' fences. At this time, there were no clear borders for lands claimed by Native Americans, Mormons, or lands the Americans bought from Mexico (Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo). But during the war panic, these everyday complaints turned into more serious accusations.

For example, according to John D. Lee, the travelers "swore and boasted openly... that Buchanan's whole army was coming right behind them, and would kill every God D***n Mormon in Utah.... They had two bulls which they called one 'Heber' and the other 'Brigham,' and whipped 'em through every town, yelling and singing... and blaspheming oaths that would have made your hair stand on end."

While Jacob Hamblin was in Salt Lake City, he heard that the Fanchers had "behaved badly [...and had] robbed hen-roosts, and been guilty of other irregularities, and had used abusive language to those who had remonstrated with them. It was also reported that they threatened, when the army came into the north end of the Territory, to get a good outfit from the weaker settlements in the south."

John Hawley, traveling home to Washington, Utah Territory, caught up with the Fancher Party 150 miles south of Provo and traveled with them for 3 days. Hawley found them to be families with a large group of cattle, all going to settle in California. The captain told him they had trouble with the Mormons at Salt Creek and Provo. This happened when their cattle went into the Mormon's grazing land, and a German man in their group would not obey the local authorities. The captain told Hawley that they intended to obey all the laws and rules of the territory. Hawley later said, "I am satisfied the Saints gave them more trouble than they ought."

In his report about the massacre, Jacob Forney, who was in charge of Native American affairs in Utah Territory, said: "I [...made] strict inquiry relative to the general behavior and conduct of the company towards the people of this territory ..., and am justified in saying that they conducted themselves with propriety."

In Forney's interview with David Tullis, who had been living with Jacob Hamblin, Tullis said that "[t]he company passed by the house...towards evening.... One of the men rode up to where I was working, and asked if there was water ahead. I said, yes. The person who rode up behaved civilly."

In addition, William Rogers later said that Shirts (another person) related he "saw the emigrants when they entered the valley, and talked with several of the men belonging to it. They appeared perfectly civil and gentlemanly."

Brigham Young and Native American Relations

Brigham Young, as the leader of Native American Affairs in the Utah Territory, had strong relationships with the area's Native American tribes. When it became clear that U.S. troops would invade, he tried to get them to join Mormons in fighting the "Americans."

On August 4, 1857, Young told Jacob Hamblin that he was now the President of the Santa Clara Indian Mission. He told Hamblin to continue being friendly with the Native Americans. Young said, "...they must learn that they either got to help us, or the United States will kill us both."

Young sent his trusted interpreter Dimick B. Huntington to various tribes with wagons full of food. Huntington told Native Americans that the Utah War was a battle, predicted in the Book of Mormon. He said it was a fight between Mormons and Native Americans on one side, and "gentiles" (non-Mormon white people) on the other. Young's message for the tribes was that they should "be at peace with all men except the Americans." Experts disagree whether Young meant Native American tribes should fight all non-Mormon Americans, including travelers, or just the approaching U.S. Army.

Leader of the Mormon mission to Native Americans

Huntington did not express disapproval when Shoshones told him that cows, horses, and mules had been stolen from Californians. Wilford Woodruff recorded Young's message to the Mormon leaders on August 26, 1857: "The Gentile emigrants [will] shoot the indians wharever they meet with them & the Indians now retaliate & will kill innocent People." On August 30, 1857, Huntington gave a group of northern tribes "all the beef cattle & horses that was on the road to Cal[i]fornia, the North rout[e]."

On September 1, 1857, a frontiersman named James Gemmell was in Young's office with Hamblin. Hamblin had come with a group of tribal leaders (including Ammon, Kanosh, Tutsegabit, and Youngwuds). George A. Smith was also with them on his return to Salt Lake. All of them had camped near the Baker–Fancher party.

When Hamblin told Young that the Arkansas train was near Cedar City, Young said, according to Gemmell, that if he were in charge of the Nauvoo Legion, he "would wipe them out." These chiefs then met with Huntington and Brigham Young. There, the Native American leaders were given "all the cattle that had gone to Cal. the south rout[e]." The Native American leaders questioned this, because before, the Mormons had told them not to steal cattle. Young admitted this, but said, "now they have come to fight us & you, for when they kill us then they will kill you." Modern experts generally agree that Brigham Young was giving Native American leaders permission to steal cattle from travelers. There is also evidence that this policy of Native Americans stealing cattle was put into effect against other traveling groups besides the Fancher–Baker party.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |