War in the Vendée facts for kids

Quick facts for kids War in the Vendée |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolutionary Wars | |||||||

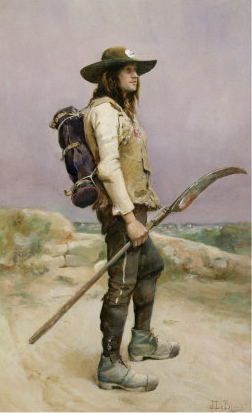

Henri de La Rochejaquelein at the Battle of Cholet in 1793, by Paul-Émile Boutigny |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Supported by: |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 130,000–150,000 | 80,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| c. 30,000 military killed | Several tens of thousands killed | ||||||

|

|||||||

The War in the Vendée (French: Guerre de Vendée) was a major uprising in France from 1793 to 1796. It happened in the Vendée region, which is in western France, south of the Loire River. This conflict was part of the larger French Revolutionary Wars.

At first, the revolt was like a peasant uprising, similar to others in history. But it quickly became a fight against the French Revolution and for the return of the king (Royalist). The rebels formed the Catholic and Royal Army. This war was similar to another uprising called the Chouannerie, which happened north of the Loire River.

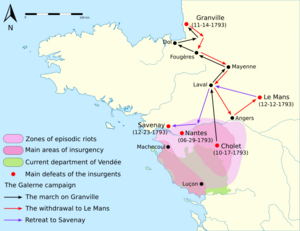

While other revolts against new army rules were stopped, a large rebel area formed in the Vendée. Historians called this area the Vendée militaire. The rebels, known as "Vendeans," created their "Catholic and Royal Army" in April 1793. They won many battles that spring and summer. They briefly took control of towns like Fontenay-le-Comte, Thouars, Saumur, and Angers. However, they could not capture Nantes.

In the autumn, the Republican army got stronger with new troops. They took back Cholet, a key city for the Vendeans. After this defeat, most Vendean forces crossed the Loire River. They marched towards Normandy, hoping to reach a port. Their goal was to get help from the British and French nobles who had left France. But they were pushed back at Granville. The Vendean army was finally defeated in December at Mans and Savenay.

From late 1793 to early 1794, during a period called the Reign of Terror, the Republican forces used harsh methods. In cities like Nantes and Angers, thousands of people were executed. In the countryside, many civilians were killed by special Republican units. These units also burned many towns and villages.

This harsh treatment caused the rebellion to start again. In December 1794, the Republicans began talking with the Vendean leaders. This led to peace treaties in 1795, ending the "first Vendée war." A "second Vendée war" began in June 1795, but it quickly faded. The last Vendean leaders were defeated or executed by July 1796. There were smaller uprisings later in 1799, 1815, and 1832. About 200,000 people died in the conflict. This was about 20-25% of the population in the rebel areas.

Contents

Why the War Started

In the rural Vendée region, local noble families often lived among the peasants. This was different from other parts of France, where nobles usually lived in cities. Because of this, the usual class conflicts that fueled the revolution in Paris were less strong here. The Catholic Church was also very powerful in the Vendée, working closely with the nobles.

Some people believed that the new Republican government wanted to weaken the Catholic Church in France. The people of the Vendée found this idea very upsetting. In 1791, officials told the French government that the Vendée was preparing to rebel. This was followed by news of a plot by a royalist noble.

People who supported the Vendée rebels argued that their actions were a response to several things. These included the harsh period known as The Terror, where many people were executed. Another reason was the Civil Constitution of the Clergy (1790). This law forced priests to support the new government instead of the Pope. Also, a new rule in February 1793 forced many men across France to join the army. This was called conscription.

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy made all Catholic priests promise loyalty to the new French government. Most bishops and about half of the local priests refused this oath. They wanted to remain loyal to the Pope. The government's actions against the Church and its push to remove religion from French culture angered many. This, along with the forced army service, sparked the Vendée uprising. The Vendeans took up arms as "The Catholic Army," later adding "Royal" to their name. They fought mainly to reopen their churches and bring back their old priests.

While many in the Vendée supported the rebellion, some peasants in towns supported the Revolution. This was especially true for tenant farmers on Church lands. They liked the Revolution because Church lands were taken and given to them. However, most of the land was bought by middle-class people, not by the peasants themselves.

How the Revolt Began

In March 1793, many parts of France saw riots when the government tried to force men into the army. In the northwest, these riots were very strong. By early April, the government had stopped the unrest north of the Loire River. But south of the Loire, in four areas known as the Vendée militaire, there were few soldiers to control the rebels. What started as riots quickly became a full rebellion, led by priests and local nobles.

Within a few weeks, the Royalist forces grew into a large army. They were called the Royal and Catholic Army. They were not well-equipped but had about two thousand irregular cavalry and some captured cannons. The main Royalist forces often used guerrilla tactics. They used their local knowledge and community ties to fight the government troops.

Where the Fighting Happened

The rebellion happened in an area about 60 miles wide. This area did not fit neatly into the new French administrative regions. The heart of the rebellion was in the forests around Cholet. It included parts of old Anjou, Poitou, and the Breton marshlands. This covered parts of the departments of Maine-et-Loire, the Vendée, and Deux Sèvres. However, the Royalists never fully controlled the entire area. The further a place was from Paris, the more likely it was to be involved in the anti-Revolutionary fight.

End of the First War and Later Uprisings

After the important Battle of Savenay in December 1793, the government ordered people to leave the area. They also started a "scorched earth" policy. This meant destroying farms, burning crops and forests, and tearing down villages. There were many reports of terrible acts and widespread killings of Vendée residents. These killings affected everyone, no matter if they were fighters, their political views, or their age or gender. Women were sometimes targeted because they were seen as having anti-revolutionary children.

From January to May 1794, between 20,000 and 50,000 Vendean civilians were killed. This was done by special Republican units called the colonnes infernales ("infernal columns"). These units were led by General Louis Marie Turreau. Among those killed were many religious figures. In the Anjou region, Republicans captured thousands of Vendeans. Many were shot or executed, and others died from disease in prison.

In February 1794, the government ordered a final "pacification" effort, called Vendée-Vengé ("Vendée Avenged"). General Turreau asked what to do with women and children in rebel areas. He was told to "eliminate the brigands to the last man."

The government later tried to make peace. They promised the Vendeans freedom to worship and guaranteed their property. General Lazare Hoche did a good job with these measures. He returned cattle to peasants who surrendered. On July 20, 1795, he defeated a group of French nobles who had returned from England. Peace treaties were signed in February and May 1795. These treaties were mostly followed by the Vendeans. By July 16, 1796, the French government officially declared the war over.

Estimates of those killed in the Vendée conflict range from 117,000 to 450,000 people. The total population of the area was about 800,000.

The Hundred Days

The War in the Vendée was very intense from 1793 to 1799. It was mostly stopped then, but it flared up again at times, especially in 1813, 1814, and 1815. During Napoleon's Hundred Days in 1815, some people in the Vendée stayed loyal to King Louis XVIII. Napoleon had to send 10,000 soldiers to control the 8,000 Vendean rebels. This conflict ended with the Battle of Rocheservière.

Understanding the War

This short period in French history had a big impact on French politics. Some historians, like Charles Tilly, see the conflict in a simpler way. He suggested that the counter-revolution grew from the government's efforts to take direct control of the region. The government wanted to remove the power of nobles and priests. They wanted to bring government demands for taxes and soldiers directly to families and communities. This also gave power to the middle class, who had not had it before.

The Vendée revolt quickly became a symbol of the fight between the Revolution and those against it. It was also a source of extreme violence. The region and its towns were greatly affected. Even the name of the department, Vendée, was changed to Venge for a time. Towns and cities were also renamed, but in villages, the old names stayed.

Beyond arguments about whether it was a genocide, other historians see the uprising as a revolt against forced army service. This then grew to include other complaints. For several months, the government in Paris lost control of the Vendée. They thought the revolt was a plot by nobles. But historians like Mona Ozouf and François Furet say it was not. The Vendée region was not against the rest of the nation. It was not the fall of the old system that made people rebel. Instead, it was the new government's rules and ideas that the local people found unacceptable. These included new administrative maps, strict government control, and especially the rules about priests.

The rebellion first started in August 1792 but was quickly stopped. Even the execution of King Louis XVI did not cause the uprising. What truly sparked it was the forced conscription. Even though the Vendeans used "God and King" on their flags, they were fighting for their traditions, not just to bring back the old government.

In Books, Movies, and Music

The events of the Vendée War have been shown in many books, films, and songs.

Film and Television

- The Hidden Rebellion is a docu-drama filmed in France. It shows the rebellion as an example of courage and love for God and country. It won an award in 2017 and has been shown on EWTN.

- The War of the Vendée (2012) is an independent film. It won awards for "Best Film For Young Audiences" and "Best Director."

- The Vendée Revolt was the setting for an episode of the BBC's The Scarlet Pimpernel (TV series) called "Valentine Gautier" (2002).

- It was also the setting for "The Frogs and the Lobsters", an episode of the TV show Hornblower. This episode is based on real events of the Quiberon expedition of 1795.

- Vaincre ou mourir is a 2022 film made with the Puy du Fou theme park company.

Music

- The album Chante la Vendée Militaire (La Chouannerie) by Catherine Garret was released in 1977.

- The album Vendée 1792–1796 by the Chœur Montjoie Saint-Denis came out in 2005.

- The EP Guerres de Vendée: Chouans by Jean-Pax Méfret was released in 2006.

- The French black/folk metal band Paydretz creates music specifically about the Wars in the Vendée and the Chouannerie.

- La Vandeana is an Italian song about the Vendée.

Images for kids

-

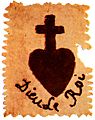

Sacred Heart patch of the Vendean royalist insurgents. The French motto 'Dieu, le Roi' means 'God, the King'.

-

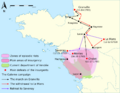

The administrative Vendée département (green), the "Military Vendée" (pink) where most of the insurrection took place and the Virée de Galerne (black, red and blue arrows)

See also

- Vendean leaders:

* Charles Melchior Artus de Bonchamps * Jacques Cathelineau * François Athanase de Charette * Maurice d'Elbée * Louis Marie de Salgues de Lescure * Henri du Vergier de la Rochejaquelein * Charles Aimé de Royrand * Jean-Nicolas Stofflet

- Republican leaders:

* Louis-Alexandre Berthier * Jean-Baptiste Carrier * Lazare Hoche * Jean-Baptiste Kléber * Antoine Joseph Santerre * François Joseph Westermann

- Other links:

* Chouannerie (another Royalist uprising) * Catholic and Royal Army * Armée des Émigrés * Drownings at Nantes (mass executions by drowning) * Dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution * Reign of Terror * Cholet * Clisson * Fontenay-le-Comte * La Roche-sur-Yon (capital of Vendée) * Ninety-Three (novel by Victor Hugo) * Marie Lourdais

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |