Western Chalukya Empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Western Chalukya Empire

Kalyani Chalukya

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 975–1184 | |||||||||||||

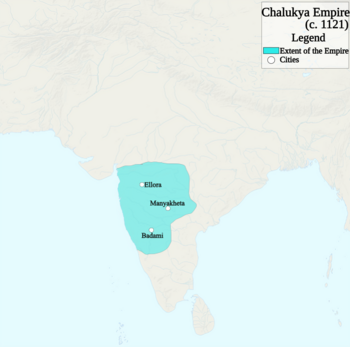

Greatest extent of the Western Chalukya Empire, 1121 AD

|

|||||||||||||

| Status | Empire (Subordinate to Rashtrakuta until 973) |

||||||||||||

| Capital | Manyakheta Basavakalyan |

||||||||||||

| Common languages | Kannada Sanskrit |

||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism Jainism |

||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

|

• 957–997

|

Tailapa II | ||||||||||||

|

• 1184–1189

|

Someshvara IV | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

|

• Earliest records

|

957 | ||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

975 | ||||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

1184 | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

The Western Chalukya Empire was a powerful kingdom in South India. It ruled most of the western Deccan Plateau from the 10th to the 12th centuries AD. This dynasty is sometimes called the Kalyani Chalukya. This is because its main capital was Kalyani, which is now Basavakalyan in Karnataka. It is also known as the Later Chalukya or Western Chalukyas. This helps tell it apart from earlier Chalukya rulers and other kingdoms.

Before the Western Chalukyas, the Rashtrakuta Empire controlled much of the Deccan. But in 973, a ruler named Tailapa II saw a chance. The Rashtrakuta capital was in trouble after an attack. Tailapa II, who was a local ruler under the Rashtrakutas, defeated them. He made their capital, Manyakheta, his own. The Chalukya kingdom quickly grew strong. Under King Someshvara I, the capital moved to Kalyani.

For over 100 years, the Western Chalukyas often fought the Chola dynasty from Thanjavur. They both wanted control of the rich Vengi region. During the rule of Vikramaditya VI (late 11th and early 12th centuries), the Western Chalukyas controlled a huge area. It stretched from the Narmada River in the north to the Kaveri River in the south. Other major kingdoms like the Hoysala Empire and the Kakatiya dynasty were under the Chalukyas. These kingdoms became independent when the Chalukya power weakened in the late 12th century.

The buildings of the Western Chalukyas are famous today. Their style connects the older Chalukya buildings with the later Hoysala ones. Many of their temples are near the Tungabhadra River in central Karnataka. Important examples include the Kasivisvesvara Temple and the Mahadeva Temple. This time was also important for art and writing in South India. The Western Chalukya kings supported writers in both Kannada and Sanskrit languages.

Contents

How the Western Chalukya Empire Began and Grew

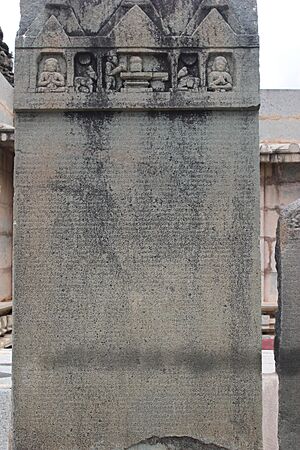

We learn about the Western Chalukya Empire from many sources. These include stone carvings called inscriptions and old writings. Most of the royal inscriptions are in the Kannada language. Famous writers like Ranna and Bilhana also wrote about this time.

The earliest records of the Western Chalukyas are from 957. At that time, Tailapa II was a local ruler under the Rashtrakuta Empire. He ruled from Tardavadi in Bijapur district. There is some debate about if the Western Chalukyas were related to an older Chalukya family. Some records suggest they were from the same family. Others say they were a new, separate family.

Tailapa II took advantage of a weak Rashtrakuta Empire. In 973, he defeated the Rashtrakutas when their capital was attacked. Tailapa II then moved his capital to Manyakheta. He made the Chalukya kingdom strong across the western Deccan. He brought other local rulers under his control.

Battles and Important Rulers

In the 11th century, the Western Chalukyas often fought with the Chola dynasty. They battled for control of the rich Vengi region. This area is now coastal Andhra Pradesh. The Eastern Chalukyas of Vengi were distant relatives of the Western Chalukyas. But they often sided with the Cholas because of family ties.

King Satyashraya followed Tailapa II as ruler. He defended his kingdom from the Cholas. In 1007, the Chola prince Rajendra Chola I attacked the Western Chalukyas. He fought King Satyashraya near Donur. Chola records say they destroyed the Chalukya capital and conquered some areas.

Jayasimha II, Satyashraya's successor, also fought the Cholas. He also brought other rulers like the Paramaras under his control.

King Someshvara I and the New Capital

Jayasimha's son, Someshvara I, became king around 1042. He moved the Chalukya capital to Kalyani. He was a very successful ruler. The fighting with the Cholas continued, with both sides winning and losing battles. In 1068, Someshvara I and his son Vikramaditya VI lost a battle against the Cholas. After this, Someshvara I, who was very ill, ended his life in the Tungabhadra River.

Someshvara I kept control of the northern parts of his kingdom. But after his death, his sons, Someshvara II and Vikramaditya VI, fought each other. Vikramaditya VI was a strong warrior. He had even attacked Bengal before becoming king. He gained the support of other local rulers. In 1075, Vikramaditya VI overthrew his brother and became the Western Chalukya Emperor.

The Reign of Vikramaditya VI

The 50-year rule of Vikramaditya VI was a very important time. Historians call it the "Chalukya Vikrama era." He was the most successful of the later Chalukya kings. He kept his powerful local rulers in check. He also defeated the Cholas in battles in 1093 and 1118. He controlled a vast area, from the Kaveri River in the south to the Narmada River in the north. He was called Permadideva and Tribhuvanamalla (lord of three worlds).

Scholars praised Vikramaditya VI for his military skills and his love for arts. He also allowed different religions. Many writers in Kannada and Sanskrit were part of his court. The poet Bilhana wrote a famous book about him called Vikramankadeva Charita. Vikramaditya VI was also a religious king. He made many grants to scholars and religious places.

The Decline of the Empire

The constant wars with the Cholas made both empires weaker. This gave their local rulers a chance to become more independent. After Vikramaditya VI died in 1126, the Chalukya Empire slowly shrank. Between 1150 and 1200, there were many battles. The Chalukyas fought their own local rulers, and these rulers also fought each other.

By the time of Jagadhekamalla II, the Chalukyas had lost Vengi. His successor, Tailapa III, was even captured by the Kakatiya king in 1149. This greatly hurt the Chalukyas' reputation. Other kingdoms like the Hoysalas and Seunas started taking over Chalukya lands.

In 1157, the Kalachuris of Kalyani took over Kalyani, the Chalukya capital. The Chalukyas had to move their capital to Annigeri. The Kalachuris ruled for about 20 years. In 1183, the last Chalukya ruler, Someshvara IV, tried to get back control. He recaptured Kalyani. But other powerful rulers like Hoysala Veera Ballala II and Seuna Bhillama V were also expanding.

Someshvara IV's efforts to rebuild the empire failed. The Seuna rulers finally ended the Chalukya dynasty in 1189. They forced Someshvara IV into exile. After the Chalukyas fell, the Seunas and Hoysalas continued to fight over the Krishna River region. This period saw the end of two great empires: the Western Chalukyas and the Cholas. New kingdoms rose from their ruins.

How the Western Chalukya Empire Was Run

The Western Chalukya kingship was passed down through the family. If a king had no sons, his brother would become king. The empire's government was not very centralized. Local rulers, like the Hoysalas and Kakatiyas, were allowed to rule their own areas. They paid a yearly tribute to the Chalukya emperor.

Records show important government positions. These included Mahapradhana (Chief Minister) and Dharmadhikari (Chief Justice). Many ministers were also trained as army commanders. This showed they had both administrative and military skills.

The kingdom was divided into large provinces called Mandala. These had names like Banavasi-12000, meaning they had 12,000 villages. These large provinces were then split into smaller ones. A Mandala was usually led by a member of the royal family or a trusted official. Even women from the royal family sometimes governed these areas.

Money and Coins

The Western Chalukyas made gold coins called pagodas. These coins had Kannada and Nagari writing on them. They were thin gold coins with symbols like a lion or the king's title. Different kings had different titles on their coins. For example, Someshvara I used Sri Tre lo ka malla.

The main places for making coins were Lakkundi and Sudi. The heaviest gold coin was the Gadyanaka. Other coins included the Dramma, Kalanju, and Kasu.

Economy and Trade

Farming was the main way the empire made money. Taxes were collected on land and crops. Most people lived in villages and grew rice, pulses, and cotton. Sugarcane was grown in areas with good rain. People seemed to have fair living conditions. If farmers were unhappy, they would move to another ruler's land. This would cause the ruler to lose tax money.

Taxes were also collected on mining and forest products. There were tolls for using roads and other transport. The state also got money from customs, business licenses, and court fines. Horses and salt were taxed, along with goods like gold, textiles, and perfumes.

Local officials called Gavundas were important in rural areas. They represented the people to the rulers. They also helped collect taxes and raise local armies. They were involved in land deals and village council duties.

Business and Guilds

In the 11th century, businesses started to organize into groups called guilds. Almost all arts and crafts had guilds. Merchants formed powerful guilds that worked across different kingdoms. This helped their businesses continue even during wars. Their main worry was theft from robbers when traveling.

Important merchant guilds included the Manigramam and the Ainnurruvar. The Ainnurruvar was the richest and most powerful. They traded by land and sea, helping the empire's foreign trade. They were proud of their business and recorded their achievements in inscriptions.

Rich traders paid a lot of money to the king through import and export taxes. The Aihole Svamis traded with many foreign kingdoms. These included places like China, Malaysia, Persia, and Nepal. They traded valuable items like precious stones, spices, and perfumes. Diamonds, emeralds, and saffron were common trade goods.

The Western Chalukyas controlled most of South India's west coast. By the 10th century, they traded with the Tang Empire of China and other Asian empires. Chinese ships often visited Indian ports by the 12th century. India exported textiles, spices, and jewels to China. These goods also went to ports in the west, like Dhofar and Aden. The final stops for western trade were Persia, Arabia, and Egypt.

The most expensive import was Arabian horses. Arab and local Brahmin merchants controlled this trade. It was hard to breed horses in India because of the climate.

Culture and Society

Religion in the Empire

The fall of the Rashtrakuta Empire and other events affected Jainism. Interest in Jainism decreased, but the new kingdoms still allowed all religions. Hinduism, especially the Virashaiva and Vaishnava faiths, grew stronger. Buddhism had already started to decline in South India. Only a few Buddhist worship places remained. There are no records of religious fights, showing a peaceful change.

The Virashaiva faith grew strong in the 12th century. This was thanks to Basavanna and other saints. Basavanna taught about a faith without a caste system. He wrote poems in simple Kannada, saying "work is worship." These Virashaivas, also called Lingayats, questioned old traditions. They supported widows remarrying and older women getting married. This gave women more social freedom.

Ramanujacharya, a Vaishnava leader, also taught in the Hoysala area. He preached about devotion to God. His teachings led to the Hoysala King Vishnuvardhana becoming a Vaishnava. This change had a big impact on culture, writing, and buildings in South India. Many important poems and books were written based on these new ideas.

Daily Life and Education

The rise of Veerashaivism challenged the old Hindu caste system. Women's roles depended on their wealth and education. Royal and rich urban women had more freedom. Records show women were involved in arts like dance and music. Some royal women, like Princess Akkadevi, even helped in administration and fought in battles.

Brahmins had a special place in society. They provided knowledge and local justice. They usually worked in religion and learning. Kings and rich people supported Brahmins by giving them land and homes. Brahmins were seen as wise and helped educate communities. They also helped solve local problems as neutral judges.

People ate different foods. Brahmins, Jains, and Buddhists were strict vegetarians. Other groups ate various meats, including goat, sheep, and fowl. For fun, people watched wrestling matches or animal fights. Horse racing was also popular. Festivals and fairs were common, with acrobats, dancers, and musicians.

Schools and hospitals were often built near temples. Marketplaces were like town halls where people discussed local issues. Choirs sang religious songs at temples. Young men learned to sing in schools attached to monasteries. These places offered advanced education in religion and ethics. They had good libraries. Learning was in both local languages and Sanskrit. Higher learning schools were called Brahmapuri. Brahmins mostly taught Sanskrit. Students learned subjects like economics, political science, and philosophy.

Literature and Writing

The Western Chalukya period was a time of great writing in Kannada and Sanskrit. Jain scholars wrote about their religious leaders. Virashaiva poets wrote short, powerful poems called Vachanas. Nearly 300 Vachana poets are known, including 30 women. Early Brahmin writers focused on Hindu epics and religious texts. For the first time, books on topics like romance, medicine, and math were written.

Famous Kannada writers included Ranna and Nagavarma II. Ranna was called "Emperor among poets" by King Tailapa II. He wrote five major works. His Saahasabheema Vijayam praised King Satyashraya. He also wrote Ajitha purana about a Jain leader.

Nagavarma II was a poet in King Jagadhekamalla II's court. He wrote important works on poetry, grammar, and vocabulary. His books are still important for studying the Kannada language. Many medical books were also written during this time.

A unique form of Kannada poetry, called Vachanas, developed then. Mystics wrote these simple poems to express their love for God. Basavanna, Akka Mahadevi, and Allama Prabhu are the most famous Vachana poets.

In Sanskrit, the Kashmiri poet Bilhana wrote a long poem called Vikramankadeva Charita. It tells the story of King Vikramaditya VI's life. The great Indian mathematician Bhāskara II also lived during this time. He wrote important books on math and astronomy.

King Someshvara III wrote Manasollasa (1129). This Sanskrit book was like an early encyclopedia. It covered many topics, including medicine, magic, and music. It helps us understand the knowledge of that time.

A Sanskrit scholar named Vijnaneshwara wrote Mitakshara. This was a famous book on law in King Vikramaditya VI's court. It is still important in Indian law today.

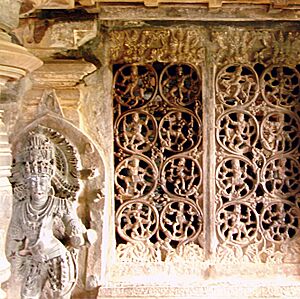

Architecture and Buildings

The Western Chalukya period was key for building design in the Deccan. Their style connected the older Badami Chalukya buildings with the later Hoysala ones. Their art is sometimes called the "Gadag style." This is because of the many beautiful temples they built in the Gadag district. By the 12th century, they had built over a hundred temples.

Besides temples, they were known for their ornate stepped wells called Pushkarni. These were used for ritual bathing. The Hoysalas and Vijayanagara empires later used these designs.

Some of the best examples of their temples include the Kasivisvesvara Temple at Lakkundi and the Mahadeva Temple at Itagi. The Mahadeva Temple from the 12th century is known for its detailed sculptures. An inscription calls it "Emperor of Temples." The Kedareswara Temple (1060) at Balligavi shows a mix of Chalukya and Hoysala styles.

Chalukya architects were known for their turned pillars. They also used Soapstone for building and sculptures. This became very popular in later Hoysala temples. They also used decorative Kirtimukha (demon faces) in their carvings. Their art and sculptures followed the dravidian architecture style. This style is sometimes called Karnata dravida.

Language and Inscriptions

The local language, Kannada, was mostly used in Western Chalukya inscriptions. Some historians say 90 percent of their inscriptions are in Kannada. The rest are in Sanskrit. King Vikramaditya VI had more Kannada inscriptions than any other king before the 12th century.

Inscriptions were carved on stone (Shilashasana) or copper plates (Tamarashasana). This period saw Kannada grow as a language for literature and poetry. The Virashaiva movement especially helped this. They wrote simple poems called Vachanas.

For official records, Kannada was used to describe land grants and local rights. If an inscription was in two languages, Sanskrit was used for the king's titles and history. Kannada was used for the details of the grants. This made sure local people clearly understood the information.

Besides inscriptions, historical records called Vamshavalis were written. These gave details about the ruling families. Sanskrit writings included poetry, grammar, and commentaries. In Kannada, books on everyday topics became popular. These included books on poetry, romance, medicine, and astrology.

Images for kids