Western Mexico shaft tomb tradition facts for kids

The Western Mexico shaft tomb tradition describes a special way people buried their dead in ancient times. This tradition was found in the western Mexican states of Jalisco, Nayarit, and Colima. It lasted for about 700 years, from around 300 BCE to 400 CE.

Most of the items from these tombs were found by people who were not archaeologists. This makes it hard to know exactly when and where they came from. The first undisturbed shaft tomb was only found in 1993 in Huitzilapa, Jalisco.

For a long time, people thought these tombs were made by the Purépecha people, who lived much later. But by the mid-1900s, research showed that the tombs and their treasures were actually over a thousand years older. Because so little was known, a 1998 art show about these items was called "Art and Archaeology of the Unknown Past."

Today, experts believe that even though shaft tombs are found across this area, it wasn't one single culture. Archaeologists are still working to understand and name the ancient groups who created these amazing tombs.

Contents

What Are Shaft Tombs?

The shaft tomb tradition likely began around 300 BCE. Some shaft tombs, like one at El Opeño in Michoacán, are even older. But these very old ones are linked to Central Mexico, not Western Mexico. The exact beginnings of the tradition are still a bit of a mystery. However, the valleys around Tequila, Jalisco, including sites like Huitzilapa, are seen as the main area where it started. The tradition continued until at least 300 CE.

Western Mexico shaft tombs have a unique design. They feature a vertical shaft, like a deep well, dug 3 to 20 meters (about 10 to 65 feet) down. This shaft goes into the soft volcanic rock called tuff. At the bottom, the shaft opens into one or two (sometimes more) horizontal rooms. These rooms might be about 4 by 4 meters (13 by 13 feet) with low ceilings. Often, a building was built right above the tomb entrance.

Many people were buried in each tomb chamber. This suggests that families or important groups used the tombs over many years. Building these tombs took a lot of effort. The valuable items found inside also show that only the most important people, or "elites," were buried there. This tells us that these ancient societies were very organized and had different social classes.

Sites like El Opeño and La Campana in Colima also have some shaft tombs. These are often connected to the Capacha culture.

Ceramic Figures and Scenes

Inside these tombs, archaeologists found many interesting items. These "Grave goods" included hollow ceramic figures, obsidian and shell jewelry, and shiny semi-precious stones. There was also pottery, which often held food, and tools like spindle whorls for spinning thread and metates for grinding grain. Some unusual finds include conch shell trumpets decorated with plaster.

Unlike art from other ancient cultures like the Olmec or Maya, shaft tomb artifacts usually don't have many symbols. This means their religious or secret meanings are harder to understand.

The many ceramic figures found have drawn the most attention. They are some of the most striking art from Mesoamerica. These ceramics seem to have been the main way these cultures expressed themselves through art. There are almost no large buildings, stone carvings (like stelae), or other public artworks from this time.

Since most of these ceramics were found by looters, we don't know their exact origin. So, experts mostly study their different styles and what they show.

Art Styles

Here are some of the main art styles found in shaft tomb ceramics:

- Ixtlan del Rio: These figures are more abstract. They have flat, square-shaped bodies and very styled faces with nose rings and many earrings. Sitting figures have thin, rope-like arms and legs. Standing figures have short, thick limbs. An early expert, Miguel Covarrubias, said this style was like "absurd, brutal caricature."

- "Chinesca" or "Chinesco": Art dealers gave these figures this name because they thought they looked like Chinese art. This early style is from Nayarit. There are up to five main groups within this style. Type A figures, called "classic Chinesco," look very realistic. One expert, Michael Kan, said their calm look "suggests rather than demonstrates emotion." These Type A figures are so similar that they might have been made by one art "school." Types B through E are more abstract. They have puffy, slit-like eyes that blend into the face, and wide, rectangular or triangular heads. These figures often sit or recline, with short, rounded legs that quickly narrow to a point.

- Ameca: This style is from Jalisco. Figures have long faces and high foreheads, often with braids or turban-like hats. The nose is long and hooked. The large eyes are wide and staring, with clear rims made by adding separate clay strips. The wide mouth is closed or slightly open. The large hands have carefully shaped nails.

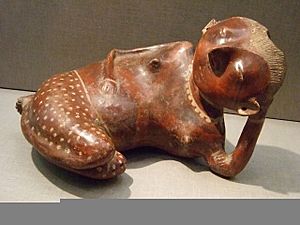

- Colima: Colima ceramics are known for their smooth, round shapes and warm reddish-brown color. Colima is especially famous for its many animal figures, particularly dogs. Human figures in the Colima style are more "controlled and less lively" than other shaft tomb figures.

Other styles include El Arenal, San Sebastián, and Zacatecas. While experts generally agree on these styles, there are some differences. Also, many figures mix styles, making them hard to categorize.

What the Figures Show

Common subjects in shaft tomb ceramics include:

- Ceramic scenes: These show several, or even dozens, of people doing everyday activities. Found mostly in highland Nayarit and Jalisco, these scenes give us a lot of information. They show ancient burial customs, the Mesoamerican ballgame, and even how houses were built. They might also show ancient religious ideas during the late Formative period. Some scenes are very detailed, almost like photographs.

- Ceramic dogs: Many dog figures are known from looted tombs in Colima. In Mesoamerican cultures, dogs were often believed to guide the souls of the dead. Some dog figures even wear human masks. However, it's also important to remember that dogs were a major source of food in ancient Mesoamerica.

- Ancestor pairs: Pairs of female and male figures are common among shaft tomb items. These figures, perhaps representing ancestors or married couples, might be joined or separate. They are often made in the Ixtlán del Río style.

- Horned figures: Many shaft tomb figures, from different styles and places, wear a horn high on their forehead. There are several ideas about these horns. They might show that the figure is a shaman (a spiritual leader). They could also be abstract conch shells, which were common tomb items and a sign of leadership. These ideas could all be true at the same time.

How They Were Used

These ceramic figures were clearly placed in tombs as grave goods. But we don't know if they were made just for burial, or if people used them before they died. Some ceramics do show signs of wear, but it's not clear if this was common.

Connections to Other Cultures

Western Mexico Cultures

Experts have tried to link the shaft tomb tradition to the Teuchitlán tradition. This was a complex society that lived in much of the same area as the shaft tomb tradition.

Unlike the typical Mesoamerican pyramids and rectangular plazas, the Teuchitlán tradition built central circular plazas and unique conical (cone-shaped) pyramids. This circular building style seems to be reflected in the many circular shaft tomb scenes. The Teuchitlán tradition began around the same time as the shaft tomb tradition, 300 BCE. But it lasted much longer, until 900 CE, centuries after the shaft tomb tradition ended. This suggests the Teuchitlán tradition grew out of and developed from the shaft tomb tradition.

Mesoamerican Cultures

Western Mexico is on the edge of Mesoamerica. For a long time, it was thought to be separate from the main Mesoamerican cultures. The people here seemed to be protected from many outside influences. For example, no items influenced by the Olmec have been found in shaft tombs. Also, there is no evidence of Mesoamerican calendars or writing systems. However, some Mesoamerican cultural signs, like the Mesoamerican ballgame, are present.

Despite this, the people in this area lived much like other Mesoamericans. They ate beans, squash, and maize (corn), along with chiles, manioc (a root vegetable), and other grains. They also ate animal protein from domestic dogs, turkeys, and ducks, and from hunting. They lived in houses made of wattle-and-daub with thatched roofs. They grew cotton and tobacco. They also traded obsidian (a volcanic glass) and other goods over long distances.

Shaft tombs themselves are not found anywhere else in Mesoamerica. The closest similar tombs are from northwestern South America.

South American Shaft Tombs

Shaft tombs also appear in northwestern South America, but a bit later than in Western Mexico (for example, around 200-300 CE in northern Peru). Dorothy Hosler, an expert from MIT, said, "The physical similarities between the northern South American and West Mexican tomb types are unmistakable." However, other experts disagree. They don't think similar tomb shapes necessarily mean the cultures were connected.

Still, other links between Western Mexico and northwestern South America have been suggested, especially regarding how metalworking developed. See Metallurgy in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

How We Learned About Them

The first major book to talk about shaft tomb items was Unknown Mexico by Carl Sofus Lumholtz in 1902. This Norwegian explorer showed pictures of grave goods and described a looted shaft tomb he visited in 1896. He also visited the ruins of Tzintzuntzan, the capital of the Tarascan state, about 250 km (155 miles) to the east. He was one of the first to mistakenly call the shaft tomb items "Tarascan."

In the 1930s, artist Diego Rivera started collecting many Western Mexico artifacts. His interest helped spark public interest in these ancient treasures. In the late 1930s, a leading archaeologist of Western Mexico, Isabel Truesdell Kelly, began her studies. From 1944 to 1985, Kelly published many papers on her work. In 1948, she was the first to suggest the idea of the "shaft tomb arc." This describes how shaft tomb sites are spread across Western Mexico (see the map above).

In 1946, Salvador Toscano questioned if the shaft tomb items were really from the Purépecha people. Miguel Covarrubias agreed in 1957, stating that Purépecha culture only appeared "after the 10th century." Later, radiocarbon dating of charcoal and other organic remains from looted tombs proved Toscano and Covarrubias right. These tests were done in the 1960s by Diego Delgado and Peter Furst. Furst also studied the modern-day Huichol and Cora peoples of Nayarit. He suggested that the artifacts were not just simple pictures of ancient people. He believed they held deeper meanings. For example, the model houses showed the living dwelling connected to the dead. He thought the horned warriors were shamans fighting mystical forces.

In 1974, Hasso von Winning published a detailed way to classify Western Mexico shaft tomb artifacts. This classification, which includes the Chinesco A through D types, is still widely used today.

The discovery of an undisturbed shaft tomb at Huitzilapa in 1993 was a very important event. It gave experts "the most detailed information to date on the funerary customs" linked to the shaft tomb tradition.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Tradición de las tumbas de tiro para niños

In Spanish: Tradición de las tumbas de tiro para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |