William Bolts facts for kids

William Bolts (born 1738, died 1808) was a British merchant who was born in the Netherlands. He worked for the East India Company in India before becoming an independent trader. He is famous for his 1772 book, Considerations on India Affairs. This book described how the East India Company managed things in Bengal after their victory in the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Bolts's observations are a great source for people studying the Company's rule in Bengal. Throughout his life, Bolts kept trying out new trading ideas on his own or with partners. Traders like Bolts helped governments and big companies expand their own business interests.

Contents

Early Life and Work

William Bolts was born in Amsterdam on February 7, 1738. Records from the English Reformed Church in Amsterdam show he was baptized on February 21, 1738. His parents were William and Sarah Bolts.

Working for the East India Company

When Bolts was fifteen, he moved to England. In 1755, he lived in Portugal and worked in the diamond trade for a while. Four years later, Bolts went to Bengal, where he worked for the East India Company in Calcutta. He learned to speak Bengali, adding to his other languages: English, Dutch, German, Portuguese, and French. Later, he worked at the Company's factory in Benares (Varanasi). There, he opened a shop for wool clothes, helped make saltpeter (used in gunpowder), imported cotton, and promoted the diamond trade from mines in Bundelkhand.

Bolts had problems with the East India Company in 1768. This might have been because Company employees often secretly sent home money they made from private trading in India, which was against the rules. In September 1768, he announced he wanted to start a newspaper in Calcutta. This would have been India's first modern newspaper. He said he had "many things to communicate which most intimately concerned every individual." However, he was told to leave Bengal and go to Madras, then sail to England. Company officials said he was bankrupt, which he later claimed caused him "irretrievable loss of his Fortune." He never seemed to get back into the Company's good graces and continued to fight against his many opponents within it.

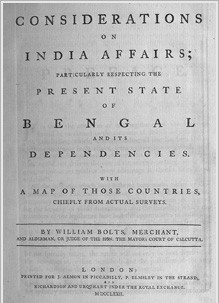

His Book: "Considerations on India Affairs"

In 1772, Bolts published his book, "Considerations on India Affairs." In this book, he criticized how the East India Company ran things in Bengal. He especially complained about the unfair power the authorities had and about being forced to leave India. Considerations was translated into French and became very popular, making him well-known in Europe. His observations and experiences in the book are still a valuable resource for people studying the nature of Company rule in Bengal.

New Adventures and Challenges

In 1775, Bolts offered his services to the Austrian government. He suggested restarting Austrian trade with India from the port of Trieste. Empress Maria Theresa accepted his idea. On September 24, 1776, Bolts sailed from Leghorn (today's Livorno) to India. He commanded a ship called the Giuseppe e Teresa (also known as Joseph et Thérèse), which sailed under the Austrian flag. He had a ten-year permit to trade under Austrian colors between Austria's ports and places like Persia, India, China, and Africa. This project needed a lot of money, so Bolts found investors in Belgium, including the banker Charles Proli.

Trying to Settle Delagoa Bay

In the next few years, Bolts set up trading posts on the Malabar Coast, at Delagoa Bay in Southeast Africa, and in the Nicobar Islands. His goal for Delagoa Bay was to use it as a base for trade between East Africa and India's west coast. He bought three ships for this "country" trade, which was how Europeans traded between India and other non-European places. During his trip, he brought cochineal beetles from Brazil to Delagoa Bay. These insects were used to make red dyes.

The Austrian flag didn't fly over Delagoa Bay for long. Portuguese authorities, who claimed the area, sent a warship and 500 men from Goa to remove Bolts's men in April 1781. They then built a fort called the Presidio of Lourenço Marques (Maputo), which established a lasting Portuguese presence there.

Trouble in India (1776-1781)

When the East India Company heard about Bolts's new venture, they told their officers in Bengal, Madras, and Bombay to "pursue the most effectual means that can be fully justified to counteract and defeat" him. Bolts used Austria's neutral status during the war between Britain and France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic (1778-1783), which was part of the American War of Independence. The Company's hostility towards Bolts in India led to complaints from the Austrian Ambassador in London. This resulted in the Company telling its officers in India in January 1782 not to offend "any subject of his Imperial Majesty."

Even though the East India Company tried to stop him when he first arrived in India at Surat, Bolts soon met Hyder Ali, the ruler of Mysore. He visited Hyder Ali at his capital, Seringapatam, and was allowed to set up trading posts in the Nawab's areas on the Malabar Coast at Mangalore, Karwar, and Baliapatam.

Claiming the Nicobar Islands

While Bolts was in Seringapatam, he sent the Joseph und Theresia to the Nicobar Islands, where it arrived in June 1778. On July 12, the ship's captain, Bennet, claimed the islands for Austria. The islands were also visited by Moravian Brethren missionaries from the Danish base at Tranquebar. Because of Bolts's actions, the Austrian company set up a trading post on Nancowery island, led by Gottfried Stahl and five other Europeans. Danish authorities strongly protested Bolts's claim to the Nicobars, and in 1783, they sent a warship to remove the Austrians.

Disagreement with His Partners

Despite his many achievements since 1776, Bolts's business had lost money overall. This upset his Belgian financial backers, Charles Proli and his partners. Proli also disagreed with Bolts about the importance of the China market. Proli wanted to focus only on China, while Bolts thought India was equally important. He believed Austrian goods like mercury, lead, copper, iron, tin, and vitriol could be sold there. In China, however, only Spanish silver coins were accepted for Chinese products like tea, porcelain, and silk.

While Bolts was still in India, the Proli group sent two ships, the Ville de Vienne to Mauritius and the Prince Kaunitz to China, without telling him. They also refused to pay the bills he sent from India. Proli asked the Austrian government to transfer Bolts's trading permit solely to him. Proli also seized the Joseph et Therese ship as security when it returned to Leghorn.

At a meeting with Emperor Joseph II in Brussels on July 28, 1781, Bolts and Proli agreed to turn their partnership into a larger company. In August, Bolts gave up his trading permits to the new Imperial Company of Trieste and Antwerp for Asian Trade. This company planned to send six ships to China and India, two to East Africa and Mauritius, and three for whaling in the south.

The Imperial Company of Trieste and Antwerp

The Imperial Company of Trieste and Antwerp started selling shares to the public in August 1781 to raise half of its capital. However, the company didn't have enough money. The other half of the shares, held by the Proli group and Bolts, were paid for by the value of their old business's assets. Bolts's valuation of these assets was accepted, but it was not accurate, and the new company inherited the old debts. Because of this, the company always lacked cash and had to take out expensive short-term loans. This meant every voyage had to be a success for the company to survive. Also, as part of the agreement, Bolts gave his trading permit to his Belgian partners in exchange for a loan of 200,000 florins (his 200 shares in the company) and the right to send two ships to China on his own.

The Imperial Asiatic Company, led by the Proli group, focused on the China tea trade. In 1781, 1782, and 1783, the price of tea in Europe, especially England, reached very high levels. In 1781 and 1782, no Dutch or French ships went to Canton (Guangzhou) because of the American War. In 1782, only eleven English, three Danish, and two Swedish ships visited. Only four out of thirteen British ships returned safely in 1783 due to French attacks. Trying to make a lot of money, the Proli group sent five ships to Canton: the Croate, the Kollowrath, the Zinzendorff, the Archiduc Maximilien, and the Autrichien.

However, they missed their chance. After a peace agreement was signed in January 1783, the countries involved in the war could send their ships to Canton safely. By the summer of 1783, there were thirty-eight ships there, including the five Austrian ones. They had to buy tea at a high price. When they returned to Ostend in July 1784, they had to sell it at a low price in a market that had too much tea. They also had to pay a fee to return to that port. The price of tea in Ostend dropped even more when the British government passed the Commutation Act in 1784. This law reduced the tax on tea from fifty to ten percent, making tea smuggling from the Netherlands unprofitable.

The price of tea in Europe suddenly fell by about sixty percent. To make things worse, a sixth ship, the Belgioioso, carrying a lot of silver to buy Chinese goods, sank in a storm in the Irish Sea shortly after leaving Liverpool. Despite growing losses and debts, the company invested in another ship, the Kaiserliche Adler or Aigle Impériale ('Imperial Eagle'). This giant 1,100-ton ship was specially built for the company and launched in March 1784, bringing the company's fleet to nine vessels.

Things came to a head in January 1785 when the company stopped all payments and was soon declared bankrupt. This also caused the Proli banking house to collapse. Charles Proli died. A newspaper article in Dublin on May 25, 1786, reported the sale of the company's ships and noted: "The destruction of this company, as well as several others in Europe, is in a great measure owing to the commutation tea tax in England, and the advantages which territorial possessions throw in favour of the British company."

New Plans for Global Trade

After Bolts returned from India in May 1781, he came up with an idea for a voyage to the North West Coast of America. He wanted to trade sea otter furs in China and Japan. He heard from his agent in Canton (Guangzhou) that the crew of James Cook's ships had made a lot of money selling sea otter pelts in November 1779. Bolts's ship, the Kaunitz (not the same as Proli's ship), returned to Leghorn (Livorno) from Canton with this news on July 8, 1781. Bolts later wrote that he wanted to be the first to profit from this new trade.

In May 1782, Bolts discussed his plan with Emperor Joseph II in Vienna. He had bought a ship in England in November 1781 for this purpose. The ship was named the Cobenzell (or Cobenzl) in honor of Count Philipp Cobenzl, a supporter of the Imperial Company. Bolts's plan was for the ship to sail around Cape Horn, pick up furs at Nootka, sell or trade them in China and Japan, and return by the Cape of Good Hope. He hired four sailors who had worked for Cook, including George Dixon and Heinrich Zimmermann. He also bought a smaller ship, the Trieste, and got official letters from the Emperor to various rulers where the ship would stop.

A Proposed Scientific Voyage

The Emperor was interested in Bolts's plan because it offered a way to fulfill his desire for an Austrian round-the-world scientific research voyage, inspired by James Cook's journeys. A famous scholar, Ignaz von Born, suggested this and, at the Emperor's request, nominated five naturalists to go with Bolts on the Cobenzell.

Although the Emperor was excited at first, he refused to provide money for the trip, except for his naturalists' expenses. The project eventually couldn't happen. Bolts's goal of a business trip and the Emperor's desire for a scientific discovery voyage didn't fit together. The opposition from Bolts's former Belgian financial partners, who were now rivals in the Imperial Asiatic Company, also contributed to the plan not moving forward. In the autumn of 1782, it was given up. Instead of a scientific expedition on an Austrian ship, the Austrian naturalists, led by Franz Jozef Maerter, sailed from Le Havre in April 1783 on an American ship to Philadelphia. From there, they traveled to South Carolina, Florida, the Bahamas, and Santo Domingo. They were to collect plants, animals, and mineral samples.

Seeking Support from Other Countries

Bolts didn't give up on his dream of a voyage to the North West coast of America. Emperor Joseph II released Bolts from his duties (except to his creditors) and allowed him in November 1782 to present his idea to Catherine II of Russia. The Russian court wasn't interested. So, Bolts also presented his idea to the court of Joseph's brother-in-law, Ferdinand IV, King of Naples. He received an encouraging response from Naples, where King Ferdinand's Minister of Commerce and the Navy, General Sir John Acton, wanted to boost the kingdom's sea trade. King Ferdinand gave Bolts a permit, similar to the one he received from Empress Maria Theresa in 1776, for a Royal Indian Company of Naples. However, the Neapolitan government agreed to support Bolts only after he completed a successful first voyage at his own expense. Preparations began in Marseille to prepare the Ferdinand, a ship Bolts planned to send to the North West Coast under the Neapolitan flag. But this venture was abandoned when Bolts received a more positive response from the French government.

Bolts and the Lapérouse Expedition

With the Emperor's permission, Bolts also presented his plan to Joseph's other brother-in-law, Louis XVI of France. Bolts explained his plan in letters he wrote to the Maréchal de Castries on January 25 and April 9, 1785. The Cobenzell would sail around Cape Horn to the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), Nootka Sound, the Kurile Islands, and China. A smaller ship would stay at Nootka to trade for furs. A couple of Frenchmen would stay in the Kuriles to learn Japanese and adopt the local customs. At least two ships would keep in touch with Europe via both the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn. A botanist, a metal expert, and an astronomer would be hired. In the South Atlantic, Tristan da Cunha was to be claimed for France and settled as a base for whaling.

The French government adopted the idea, though not Bolts himself. This led to an expedition commanded by Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse. Charles Pierre Claret de Fleurieu, Director of Ports and Arsenals, wrote to the King: "the utility which may result from a voyage of discovery ... has made me receptive to the views put to me by Mr. Bolts relative to this enterprise." However, Fleurieu explained to the King: "I am not proposing at all, however, the plan for this voyage as it was conceived by Mr. Bolts." Political and strategic reasons were more important than commercial ones. Bolts was paid 1,200 Louis for his "useful communications," but he was not involved in preparing or carrying out the Lapérouse expedition.

Later Voyages of Bolts's Ships

In mid-1782, Bolts was declared bankrupt because of his disagreements with his Antwerp backers. Even though he had no money himself, he used his reputation as an expert in Eastern trade to start a new company in 1783, the Triestine Society. In September, this society sent the Cobenzell on a trading voyage to the Malabar Coast. The ship stopped in Marseilles to pick up most of its cargo and then sailed around the Cape of Good Hope. In Bombay, a second ship was bought and named the Count of Belgiojoso. The captain of the Cobenzell, John Joseph Bauer, moved to the Belgiojoso and sailed on to China.

It was reported from Trieste on February 22, 1786, that "The Comte Cobenzel East Indiaman arrived in this port the 18th inst. with a rich cargo" of goods like saltpeter, tea, and spices. It had left Canton on January 23, 1785. The Belgioioso under Bauer sailed from Canton to New York, arriving in June 1786. The ship's arrival in Dover, England, from New York was reported on September 15. A letter from Ostend on September 24 said: "The Count de Belgioioso, on account of the East India Company, is arrived here from Bengal and China, her cargo consists chiefly of piece goods, with only a few chests of the finest teas, and one of spices, from Ceylon, at which island they touched on their way home."

The Voyage of the Imperial Eagle

Bolts had missed the chance during the American War of Independence to send a ship to the North West Coast without competitors. However, he seems to have been part of the only voyage sent there under the Austrian flag, that of the Imperial Eagle. This ship, formerly the Loudoun, sailed from Ostend in November 1786 under Charles William Barkley. The Imperial Eagle reached the Sandwich Islands in May 1787 and Nootka in June. From Nootka, it traded south along the American coast for two months. Barkley greatly added to the knowledge of the area's geography during this trip, notably identifying the Strait of Juan de Fuca. He returned to Macao with his furs on November 5. The expedition was profitable, as a newspaper reported on June 21, 1788, that "Captain Berkeley [Barkley] proceeded to Macao, where he disposed of his furs at an amazing price." The original plan was for the Imperial Eagle to make three voyages to the North West Coast, Japan, and Kamchatka. But when it reached Canton after its first season, it was sold because the East India Company threatened legal action for breaking its trade monopoly.

Plan to Settle Australia

In November 1786, Bolts received a contract from King Gustav III of Sweden. His task was to find an island off the coast of Western Australia where a Swedish colony and trading post could be set up. However, this plan was put aside after Sweden became involved in a war with Russia the following year. Bolts was paid 250 pounds for his efforts, and the proposed colony was never established.

Bolts's Final Years

Bolts reportedly tried to regain his wealth in France, starting a business near Paris. But the outbreak of war again ruined his hopes. He returned to England in 1800. There, he unsuccessfully tried to interest the East India Company in getting copper supplies from Anatolia to sell in India. He then moved to Lisbon, where he had worked in the diamond trade in the 1760s before joining the East India Company. He made his last will in Lisbon in August 1805 and is said to have died in a Paris poorhouse (hospital) in 1808.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: William Bolts para niños

In Spanish: William Bolts para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |