William Porcher Miles facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

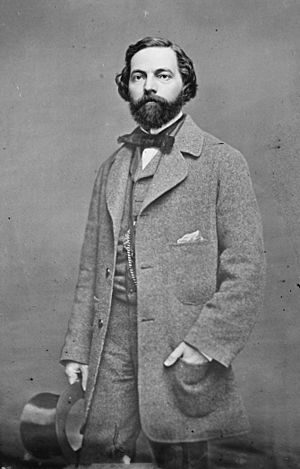

William Porcher Miles

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the C.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina's 2nd district | |

| In office February 18, 1862 – March 18, 1865 |

|

| Preceded by | New constituency |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Deputy from South Carolina to the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States |

|

| In office February 4, 1861 – February 17, 1862 |

|

| Preceded by | New constituency |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina's 2nd district |

|

| In office March 4, 1857 – December 24, 1860 |

|

| Preceded by | William Aiken |

| Succeeded by | Christopher Bowen |

| 36th Mayor of Charleston | |

| In office November 7, 1855 – November 4, 1857 |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Leger Hutchinson |

| Succeeded by | Charles Macbeth |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 4, 1822 Walterboro, South Carolina |

| Died | May 11, 1899 (aged 76) Ascension Parish, Louisiana |

| Resting place | Green Hill Cemetery, Union, West Virginia |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Betty Beirne

(m. 1863) |

| Alma mater | Charleston College |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1861 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

William Porcher Miles (July 4, 1822 – May 11, 1899) was an important political figure from South Carolina during the time leading up to and during the American Civil War. He was known for strongly supporting states' rights and the practice of slavery. He was also a key designer of the well-known Confederate flag. This flag was first rejected as a national symbol in 1861. However, it later became the battle flag for the Army of Northern Virginia, led by General Robert E. Lee.

Miles was born in South Carolina. He didn't show much interest in politics at first. He studied law and taught mathematics at the College of Charleston from 1843 to 1855. As disagreements between the North and South grew, Miles began to speak out. He believed that any efforts by the North to limit slavery would justify states leaving the Union.

Miles served as the mayor of Charleston from 1855 to 1857. He was then elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1857. He served there until South Carolina decided to leave the United States in December 1860. He was part of the convention that voted for South Carolina to secede. He also represented his state at the convention in Montgomery, Alabama, which created the Confederate States' government. During the Civil War, he represented South Carolina in the Confederate House of Representatives.

Contents

Early Life and Beliefs

William Porcher Miles was born in Walterboro, South Carolina. His family had French Huguenot roots. His grandfather, Major Felix Warley, fought in the American Revolution. Miles went to Southworth School and then Willington Academy. He later attended Charleston College, graduating in 1842. After a brief time studying law, he became a mathematics professor at his old college in 1843.

In the 1840s, Miles became more interested in political issues. He believed that efforts to restrict slavery threatened the rights of Southern states. He argued that the U.S. Constitution recognized slavery. Miles felt that Northerners trying to limit slavery were attacking the South's power and influence. He believed that any compromise on slavery was wrong.

Miles also gave speeches where he discussed ideas about liberty and government. He argued that not all people were born "free or equal." He believed that some people were naturally more capable of earning liberty than others. From this point on, Miles strongly opposed those who wanted to end slavery. He believed that any attempt to restrict slavery should lead to states leaving the Union.

Mayor of Charleston

In 1855, a serious yellow fever outbreak happened in Virginia. Miles volunteered to help as a nurse in Norfolk for several weeks. His brave actions were reported back in Charleston. This made him very popular. His friends encouraged him to run for mayor. He gave only one public speech but was elected mayor of Charleston.

As mayor, Miles wanted to make many improvements. He first focused on reforming the police department. He studied how other cities managed their police. He then put in place a plan to reduce political influence in the police force. He also increased police patrols and worked to stop repeat offenders.

Miles also worked on social reforms. He helped create a house of corrections for young people. He also established an almshouse (for the poor), an orphanage, and an asylum (for mental health care). He provided help for poor people who were traveling and for free Black people in need. He also improved the city's sewage system to boost public health. Charleston had a large public debt when he took office. Miles raised property taxes to help pay off this debt over 35 years. By the end of his two-year term, he was seen as a very successful mayor. This success led him to consider running for higher political office.

Serving in Congress

In 1856, Miles ran for a seat in the United States House of Representatives. The main issues in the election were slavery in Kansas and the growing Republican Party. Miles argued that if a Republican president was elected, Southern states might need to take strong action, possibly by leaving Congress. Miles won the election by a very close vote.

When he started his term in 1857, debates about Kansas dominated Congress. These debates caused problems within the Democratic Party and helped the Republican Party grow. Miles gave his first speech in 1858. He explained the Southern view on Kansas. Even though he knew Kansas's climate wasn't ideal for slavery, he felt it was important to fight for the principle of allowing slavery there. He believed that rejecting Kansas as a slave state would further divide the country.

Miles was re-elected in 1858. He supported the idea of allowing states to decide on the African slave trade. He felt that the federal ban on this trade was an insult to Southern honor. However, many of his friends thought this idea was too extreme. They believed it was just a way to force the Southern states to leave the Union.

The raid by John Brown on Harpers Ferry in 1859 shocked the South. When Congress met, they had to choose a speaker. Southerners were upset when John Sherman, a Republican, was nominated. Sherman had supported a book called The Impending Crisis. Southerners believed this book would cause conflict between slaveholders and non-slaveholders. Miles even planned with South Carolina's governor to send militia to Washington if Sherman was elected. However, Sherman's nomination was withdrawn.

In South Carolina, leaders struggled to decide how to respond to these events. Governor William Henry Gist suggested a Southern convention. Miles encouraged this idea. He hoped it would lead to the creation of a Southern confederacy.

South Carolina Secedes

By 1860, William Porcher Miles was a leading supporter of secession in South Carolina. His position in Washington, D.C., allowed him to share information between the capital and Charleston. State politicians focused on the upcoming Democratic Convention in Charleston. Miles was concerned about Stephen A. Douglas, who supported allowing new territories to choose whether to allow slavery. Miles and other strong Southern leaders believed that only a party focused on Southern interests could meet the state's needs.

The convention had trouble agreeing on a party platform. Southerners opposed Douglas's idea of "popular sovereignty." They wanted federal guarantees that slavery would be allowed in all U.S. territories. Many South Carolina delegates left the convention. Miles returned to Charleston and stated that the next election would be a fight between "power against principle."

Support for secession was already strong in South Carolina before Abraham Lincoln was elected president. Miles urged for immediate action instead of just more talk. He said he was tired of "endless talk and bluster." He believed the South had everything it needed to be a powerful nation on its own. He felt the South would "lose so little and gain so much" by seceding.

Secession Winter

As secession became more likely, President James Buchanan worried about the safety of U.S. property in South Carolina. Miles was one of the South Carolina delegates who met with Buchanan. They discussed the forts in Charleston. On December 10, Miles and others told the President that the forts would not be attacked. This was "provided that no reinforcement should be sent into those forts." Buchanan questioned this, but the delegates said they were just sharing their understanding.

Miles returned to South Carolina and was elected as a delegate to the state's secession convention. He wanted quick action. On December 17, he opposed moving the convention from Columbia to Charleston. He feared that any delay could be dangerous. Miles believed that other Southern states were looking to South Carolina for leadership.

The convention voted for an ordinance of secession on December 20. Miles and other South Carolinians immediately resigned from Congress. In the following months, Miles hoped for a peaceful secession. He opposed quick military action over Fort Sumter or the Star of the West incident. In February 1861, Miles was one of eight South Carolina delegates to the Confederate Convention in Montgomery, Alabama. This convention officially established the Confederacy.

Confederate Congress and the Flag

Miles was chosen to serve in both the temporary and regular Confederate Congress. He led the House Military Affairs Committee. He also worked as an aide for General P. G. T. Beauregard at Charleston, before the attack on Fort Sumter, and at the First Battle of Bull Run. However, Miles knew he lacked military training. So, he focused most of his attention on his duties in Congress.

Miles found his time in the Confederate Congress challenging. He had wanted to remove all trade taxes in a Southern confederacy. But others warned him that this would upset sugar planters in the South. Miles also complained that his colleagues often missed meetings, making it hard to get work done. As the war continued, he became unhappy with President Jefferson Davis. Later in the war, when some military leaders discussed using Black soldiers in the Confederate army, Miles was confused. He understood the army's urgent needs. However, he concluded that it was a major social and political issue. He felt it would not truly help their cause to arm enslaved people.

While in the Provisional Confederate Congress, Miles chaired the "Committee on the Flag and Seal." This committee chose the "Stars and Bars" flag as the Confederacy's national flag. Miles did not like this choice. He felt it looked too much like the U.S. flag. He argued that there was no reason to keep the symbol of a government they had left.

Miles preferred his own flag design. When General Beauregard decided that a more recognizable battle flag was needed, Miles suggested his design. Even though his design had been rejected for the national flag, it later became the Confederate Battle Flag. This flag is often called a "Rebel flag" or the "Southern Cross" today. Miles's design was also used in the corner of the second and third versions of the Confederate national flag.

Later Life

Even as late as January 1865, Miles proposed a resolution in Congress. It stated that the Confederate representatives were determined to continue fighting until the United States recognized their independence.

After the war ended, Miles was very upset by the defeat. He was also bothered by how some former secessionists changed their views. He felt that politics could no longer be a path for honorable people. He believed that for any secessionist to return to public office in the reunited Union would mean losing self-respect.

In 1863, Miles married Bettie Beirne. She was the daughter of a wealthy Virginia planter. For a few years after the war, he worked for his father-in-law in New Orleans. In 1867, Miles began managing a plantation in Nelson County, Virginia. He faced financial difficulties as a farmer. In 1874, he tried to become president of the new Hopkins University in Baltimore but was not successful. He stayed on the farm and helped friends like Beauregard gather materials for their histories of the Confederacy.

In 1880, Miles became president of the newly reopened South Carolina College. After his father-in-law passed away in 1882, Miles took over the family's business interests. He moved to Houmas House in Ascension Parish, Louisiana. There, he managed several plantations. In 1892, he and his son formed the Miles Planting and Manufacturing Company of Louisiana.

William Porcher Miles died on May 13, 1899, at the age of 76. He was buried at Green Hill Cemetery in Union, West Virginia.

Images for kids