Yaanga facts for kids

Yaanga was a large village of the Tongva people (also known as Kizh). It was located near what is now downtown Los Angeles, west of the Los Angeles River. The people from this village were called Yaangavit. Before European settlers arrived, Yaanga was known as the biggest and most important village in the area.

After the Spanish arrived, the Yaangavit people were forced to work. They helped build the San Gabriel Mission and Nuestra Señora Reina de los Ángeles Asistencia. They also worked for Spanish, Mexican, and American settlers to build Los Angeles. Because the settlers needed their labor, Yaanga survived longer than many other Native American villages nearby. However, after the city of Pueblo de Los Ángeles was founded in 1781, Yaanga changed a lot. It became more like a place for people seeking safety than a traditional village. Eventually, the community was broken up.

The original village stayed mostly the same until about 1813. The Yaangavit were forced to move several times, eventually to the east side of the Los Angeles River. In 1847, the Los Angeles City Council destroyed their village under American rule. Today, buried remains from Yaanga have been found in downtown Los Angeles. These include areas near Alameda Street, the old Bella Union Hotel, Union Station, the Plaza Church, and the Metropolitan Water District Headquarters.

Contents

What Does Yaanga Mean?

Yaanga (also spelled Yangna or iyáangaʼ) was written as "Yang-Na" by the Spanish. Old records say it was a Tongva word. It meant "place of the poison oak."

Where Was Yaanga Located?

The exact original spot of Yaanga is not clear today. This is because the village was moved, destroyed, and is now covered by downtown Los Angeles. However, we know it was near downtown Los Angeles. It was just west of the Los Angeles River and under U.S. Route 101.

One study suggests the original village was about 1.4 miles southwest of the current N. Broadway Street at the Los Angeles River. It was likely in the area of Los Angeles Street between the current Plaza south towards Temple Street. This would have placed the village very close to where the Los Angeles pueblo (town) was first built in 1781.

Some historians believe Yaanga was slightly south of Los Angeles Plaza (Los Angeles Plaza Park). It may have been near or under where the Bella Union Hotel once stood. This area is now Fletcher Bowron Square. One historian thinks it's unlikely Yaanga was east of Alameda Street. This is because floods from the Los Angeles River would have washed away that area. Higher, drier ground was found farther west.

Old city council records mention that a triangular piece of land was set aside for the Yaanga natives. This land was part of the Second Settlement Plaza. It might have been cut through by a big flood in 1815. The Los Angeles River shifted west in that flood. It destroyed both the Native village and the second pueblo settlement. The plaza of this second settlement was on the north side of Aliso Street. This was a short distance west of El Aliso, the important sycamore tree. The river then flowed west for ten years. After another flood in 1825, the river shifted east. The empty riverbed was then used as a path for people to cross the river easily.

The triangular site of Yaanga was the remaining southeast part of the second settlement's plaza. The first settlement site was abandoned possibly due to two big earthquakes in December 1812. The third (and current) site of the Los Angeles Pueblo was chosen after the 1815 flood.

Finding Old Yaanga

In 1962, Bernice Johnston noted that special items were found. Some were found during the building of Union Station in 1939. Many more were found when the historic Bella Union Hotel was built in 1870. This hotel was between Main and Los Angeles streets, north of Commercial.

In 1992, Joan Brown said that old materials were found near Union Station. She explained that studies showed buried old deposits exist under and around Union Station. The station was built on three to twenty feet of dirt. This dirt was placed over the original Los Angeles Chinatown. Chinatown, in turn, was built over the remains of an Indian village. This village was thought to be Yaanga.

In 1999, excavations at the Metropolitan Water District Headquarters found an old burial site. It was linked to the Yabit people. It has also been reported that digs near the Plaza Church found beads and other items. These items were used when people were being brought into the missions.

Life Before European Arrival

Yaanga was known as one of the most powerful villages in the area. The people from Yaanga called themselves Yaangavit. Missionary records sometimes called them Yabit.

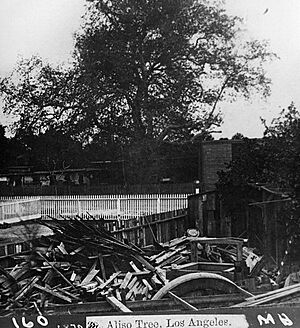

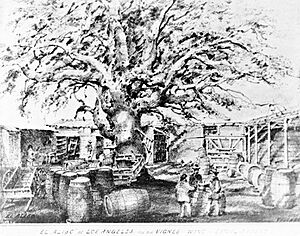

At the center of the village was a huge sycamore tree. The Spanish and later settlers called it El Aliso. This tree likely started growing in the late 1400s. It was part of a large forest along the Los Angeles River. This forest thrived until a big flood in 1825 destroyed most of the trees. However, El Aliso itself survived until 1891. This massive tree was a meeting place for the local people. It was so important that the Tongva measured distances based on it. Traders from far away, like present-day Yuma, knew the tree as a landmark. By the mid-1700s, the mighty sycamore stood in the middle of Yaanga.

In 1769, the Portolà expedition reached Yaanga. Father Juan Crespí wrote about meeting Yaangavit people on August 2: "About eight Native people from a good village came to visit us. They live in this lovely place among the trees by the River. They gave us baskets of pinole, made from sage seeds and other plants. Their chief brought strings of shell beads. They threw three handfuls of them to us. Some old men were smoking pipes made of baked clay. They blew three puffs of smoke at us. We gave them a little tobacco and glass beads, and they left very happy."

On August 3, 1769, Crespí reached the village. He described his meeting: "As they came near us, they began to howl like wolves. They greeted us and wanted to give us seeds. But we had nothing to carry them in, so we did not take them. Seeing this, they threw some handfuls on the ground and the rest in the air."

The Mission Period and Changes

When Mission San Gabriel was founded in 1771, the Spanish began calling the Yaangavit people "Gabrieleños." Mission records show that about 179 Yaangavit were baptized at San Gabriel. This was the highest number from any Tongva village. One person was baptized at San Fernando Mission.

The first town of Los Angeles was built next to Yaanga in 1781. It was built by missionaries and Native Americans who had converted to Christianity. The town was called El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula. Yaanga was used as a reference point when the founders of Los Angeles established the town. After the settlers arrived, Yaanga soon stopped working as it had for thousands of years.

In 1781, there were disagreements between the founders of Los Angeles and the Franciscan padres at Mission San Gabriel. They argued over who would control the newly converted Christian villagers. Felipe de Neve, one of Los Angeles's founders, went to Yaanga to choose children for Christian conversion. He wanted to move villagers from the Mission to the town, having them return to the missions only for religious lessons. Neve himself acted as a godfather at twelve baptisms. He even renamed one couple Felipe and Phelipa Theresa de Neve and remarried them in the church. In 1784, a sister mission, the Nuestra Señora Reina de los Ángeles Asistencia, was also founded at Yaanga.

The Yaangavit people were forced to work by the Franciscan padres. They built and worked at San Gabriel Mission and Nuestra Señora Reina de los Ángeles Asistencia. They were also forced laborers for Spanish, Mexican, and American settlers. They helped build and expand Los Angeles. In 1803, Yaanga's population was reported to be 200. As the need for Native American labor grew, the village became a place for people seeking safety from other villages. These villages had been destroyed or weakened by colonization. Historian William David Estrada says that Yaanga attracted people from local villages and islands. It also drew workers from Missions San Diego and San Luis Rey. This helped Yaanga survive longer than most other rancherías (small Native American settlements).

Moving and Dispersing the Yaangavit

The original village of Yaanga is thought to have remained mostly whole until 1813. After this, the Yaanga residents were no longer recorded in Mission San Gabriel baptism records. Researchers believe the villagers gathered again south of the original site in the 1820s. This new place was called the Ranchería de los Poblanos. In the 1820s, French immigrants came to Los Angeles. They settled near Commercial and Alameda streets, close to Yaanga's original site. The city council (ayuntamiento) passed new laws. These laws forced Native Americans to work or be arrested. They would arrest "drunken Indians," filling city jails with Tongva villagers.

The Ranchería de los Poblanos was near the Nicoleños. The Nicoleño people had been moved in a similar way in 1835. However, in 1836, Los Angeles residents complained about Native Americans bathing in the local canal. This led to the Yaangavit being forced to move again. They went to a new site on land that often flooded. This new ranchería site likely lasted less than 10 years.

A German sailor and immigrant named Juan Domingo (Johann Gröningen) lived in Los Angeles. He asked to evict the Yaangavit and get their land. Researchers note that Domingo did not wait for approval. He built a fence across one of the ranchería areas next to his property. Three representatives from the moved villages, Gabriel, Juan José, and Gandiel, protested on April 27, 1838. They asked that Domingo be forced to remove his fence so they could build their homes. The City Council made Domingo take down the fence.

However, in December 1845, Domingo bought all the land given to the villagers for $200. He took advantage of Pío Pico's need for money and the general lack of respect for Native land rights. As a result, the villagers were again forced to move. They went to a site called Pueblito, east across the Los Angeles River. This area is now Boyle Heights. This move created a separation between Mexican Los Angeles and the closest Native community. Historian Kelly Lytle Hernández wrote that "Native men, women, and children continued to live (not just work) in the city. On Saturday Nights, they even held parties, danced, and gambled at the removed Yaanga village and also at the plaza at the center of town." In response, the Californios (Mexican residents of California) tried to control the villagers' lives. In 1846, they sent a petition to Governor Pico. It asked that "the Indians be placed under strict police surveillance or the persons for whom the Indians work give [the Indians] quarter at the employer's rancho." This was despite the local economy relying heavily on Native labor.

The End of the Village

During the Mexican–American War (1846–1848), the U.S. military took over Los Angeles on August 13, 1846. Under American rule, getting rid of Native communities became a main goal. Both Anglo-Americans and Mexican citizens in Los Angeles agreed on this. On a cold evening in 1847, the Pueblito site was destroyed. The Yaangavit had only been moved there two years earlier. The Native people were scattered into smaller groups. Some moved into the city to live closer to their employers. This was reportedly approved by the Los Angeles City Council. It mostly pushed the last generation of Yaangavit into the Calle de los Negros district.

After the village was destroyed, armed attacks were launched in the city's outskirts. These attacks were approved by the state. Anglo-American Governor Peter Hardeman Burnett stated that "a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected." The U.S. federal government paid money to vigilantes who killed "Indians." Diseases also greatly affected Native people in Los Angeles. This led to a huge drop in the Native population between 1848 and 1880.

In 1852, Hugo Reid identified the historical locations of several villages in the Los Angeles Basin. These included Yaanga, before Spanish, Mexican, and American colonization. Reid published his research in the Los Angeles Star newspaper. In 1859, as more Native people were being treated as criminals and forced into labor, the county grand jury made a statement. They said that "strict vagrant laws should be made and enforced. These laws would force such persons ['Indians'] to earn an honest living or go back to their old homes in the mountains." This statement ignored Reid's research. Reid had said that most Tongva villages, including Yaanga, were in the basin. They were along its rivers and on its shoreline, from the deserts to the sea. Only a few villages led by tomyaars (chiefs) were "in the mountains." However, the grand jury ignored the deep connections Native peoples had to their land and lives. Instead, they chose to describe Native peoples as drunks and homeless people loitering in Los Angeles.

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |