Zong massacre facts for kids

The Zong massacre was a terrible event in 1781. The crew of a British slave ship called Zong threw more than 130 enslaved African people into the sea. This happened on and after November 29, 1781. The ship was owned by a group of slave traders from Liverpool, England. They had insurance on the enslaved people, just like they would for any cargo. The crew said they threw people overboard because the ship was running out of drinking water. This happened after they made mistakes navigating the ship.

After the ship reached Black River, Jamaica, the owners asked their insurance company for money. They wanted to be paid for the enslaved people who died. The insurance company refused to pay. This led to court cases. The first court case said that in some situations, killing enslaved Africans was legal. It also said that insurance companies might have to pay for those who died. The jury first sided with the ship owners. But in a later appeal, the judges, led by Lord Mansfield, ruled against the owners. New information showed that the captain and crew were at fault.

After the first trial, Olaudah Equiano, a freedman (a formerly enslaved person who gained freedom), shared news of the massacre. He told Granville Sharp, a person who fought against slavery. Sharp tried to have the ship's crew charged with murder, but he was not successful. Because of the court cases, the massacre became widely known. This helped the movement to end slavery grow in the late 1700s and early 1800s. The Zong events became a strong symbol of the horrors of the Middle Passage. This was the sea route that brought enslaved Africans to the New World.

The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed in 1787. The next year, the British Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act 1788. This was its first law to control the slave trade. It aimed to limit the number of enslaved people on each ship. Then, in 1791, Parliament stopped insurance companies from paying ship owners when enslaved Africans were thrown overboard. The massacre has also inspired many artworks and books. It was remembered in London in 2007. This was part of events marking 200 years since the British Slave Trade Act 1807. This act ended Britain's involvement in the African slave trade. A monument to the murdered enslaved Africans was put up in Black River, Jamaica.

Contents

The Ship Zong

The ship Zong was first called Zorg. This means "Care" in Dutch. Its first owners were a Dutch company. It worked as a slave ship from Middelburg, Netherlands. In 1777, it carried kidnapped Africans to the Dutch colony of Surinam in South America. Zong was a ship of 110 tons. A British ship captured it on February 10, 1781, during a war. On February 26, both ships arrived at Cape Coast Castle in what is now Ghana. This castle was a main base for the Royal African Company.

In March 1781, a group of Liverpool merchants bought Zong. This group included William Gregson. Gregson had been involved in 50 slave voyages between 1747 and 1780. He was also the mayor of Liverpool in 1762. By the end of his life, ships he owned had carried 58,000 Africans into slavery.

The Zong was bought with special payment papers. The 244 enslaved people already on board were part of the deal. The ship was not insured until after it began its voyage. The insurance company, also from Liverpool, insured the ship and its enslaved people for up to £8,000. This was about half of what the enslaved people might be sold for. The owners took the risk for the rest of the value.

The Crew

Luke Collingwood was the captain of Zong. This was his first time commanding a ship. He had been a surgeon on another slave ship. Surgeons often helped choose captured Africans to buy. They decided how much a captive was worth. If a surgeon said a captive was not valuable, that person might be killed by the African traders. Collingwood had likely seen such killings before. This might have made him more likely to accept the massacre on the Zong. The ship's first mate was James Kelsall.

The ship had only one passenger, Robert Stubbs. He used to be a captain of slave ships. In 1780, he became governor of Anomabu, a British fort in Ghana. He was forced to leave this job after nine months. Records said he was not good at managing the fort's slave trading. Stubbs was on board to return to Britain. Collingwood might have thought Stubbs's experience would be helpful.

When Zong left Africa, it had only 17 crew members. This was too few to keep the ship clean and safe. It was hard to find sailors willing to work on slave ships. Zong had a mix of its old Dutch crew, crew from another ship, and sailors hired from towns along the African coast.

The Middle Passage Journey

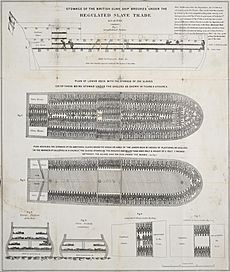

When Zong left Accra on August 18, 1781, it had 442 enslaved people. This was more than twice the number it could safely carry. In the 1780s, British slave ships usually carried about 1.75 enslaved people per ton of the ship's size. On the Zong, it was 4.0 people per ton. A typical British slave ship carried around 193 enslaved people. It was very unusual for a small ship like Zong to carry so many. After getting drinking water at São Tomé, Zong started its journey across the Atlantic Ocean to Jamaica on September 6, 1781. On November 18 or 19, the ship got close to Tobago in the Caribbean. But it did not stop there to get more water.

It is not clear who was in charge of the ship at this time. Captain Luke Collingwood had been very sick for a while. The first mate, James Kelsall, had been removed from duty after an argument on November 14. Robert Stubbs had captained a slave ship many years before. He took temporary command of Zong while Collingwood was sick. But he was not an official crew member. Historian James Walvin believes that this lack of clear leadership might explain the navigation mistakes. It also explains why no one checked the water supplies.

The Massacre

On November 27 or 28, the crew saw Jamaica about 27 nautical miles away. But they wrongly thought it was the French colony of Saint-Domingue on the island of Hispaniola. Zong kept sailing west, leaving Jamaica behind. They only realized their mistake after the ship was 300 miles past the island. Many people had already died from overcrowding, lack of food, accidents, and sickness. About 62 Africans and some sailors had died. James Kelsall later said that only four days' worth of water was left when they found the mistake. Jamaica was still 10 to 13 days away by sailing.

If the enslaved people died on land, the ship owners could not claim insurance money. If they died naturally at sea, insurance also could not be claimed. But if some enslaved people were thrown overboard to save the rest of the "cargo" or the ship, then insurance could be claimed. This is under a rule called "general average". This rule means a captain who throws part of his cargo overboard to save the rest can claim the loss from his insurers. The ship's insurance covered the loss of enslaved people at £30 per person.

On November 29, the crew met to discuss throwing some enslaved people overboard. James Kelsall later said he first disagreed. But they soon all agreed to the plan. On November 29, 54 women and children were thrown into the sea. On December 1, 42 enslaved men were thrown overboard. 36 more followed in the next few days. One enslaved person asked that the remaining Africans be denied all food and drink instead of being thrown into the sea. The crew ignored this request. In total, 142 Africans were killed by the time the ship reached Jamaica. One enslaved person managed to climb back onto the ship after being thrown into the water.

The crew said they threw the Africans overboard because there was not enough water for everyone. This was later questioned. The ship had 420 imperial gallons of water left when it arrived in Jamaica on December 22. Kelsall later stated that on December 1, when 42 enslaved people were killed, it rained heavily for more than a day. This allowed them to collect enough water for 11 days.

Arrival in Jamaica

On December 22, 1781, Zong arrived at Black River, Jamaica. It had 208 enslaved people on board. This was less than half the number taken from Africa. The survivors were sold into slavery in January 1782. They were sold for an average price of £36 per person. The ship was renamed Richard of Jamaica. Luke Collingwood died three days after Zong reached Jamaica. This was two years before the court cases about the event.

Court Cases

When news of the Zong massacre reached Great Britain, the ship's owners asked their insurance company for money. The insurers refused to pay. So, the owners took them to court. The Zong's logbook (ship's diary) disappeared after the ship reached Jamaica. So, the court cases provide almost all the written information about the massacre. There is no official record of the first trial. The insurers claimed the logbook was destroyed on purpose. The owners denied this.

Most of the information we have is from people who might have wanted to protect themselves. The two main witnesses, Robert Stubbs and James Kelsall, wanted to avoid blame. So, the numbers of people killed, the amount of water left, and the distance the ship sailed past Jamaica might not be exact.

First Trial

The court cases started because the insurance company would not pay. The first trial was in London on March 6, 1783. The main judge was Lord Mansfield. Mansfield had also been the judge in a case about slavery in Britain in 1772. In that case, he ruled that slavery was not officially legal in Britain.

Robert Stubbs was the only witness in the first Zong trial. The jury decided in favor of the ship owners. This was based on a rule in sea insurance that treated enslaved people as cargo. On March 19, 1783, Olaudah Equiano, a former enslaved person, told Granville Sharp about the events on Zong. A newspaper soon published a long story. It said the captain ordered the enslaved people killed in three groups. Sharp sought legal advice the next day. He wanted to know if the crew could be charged with murder.

King's Bench Appeal

The insurance company asked Lord Mansfield to cancel the first verdict and have a new trial. A hearing was held in London on May 21–22, 1783. Mansfield and two other judges heard the case. John Lee, a lawyer, spoke for the Zong owners. Granville Sharp was also there. He had hired someone to write down everything that was said.

Collingwood had died in 1781. Robert Stubbs was again the only witness of the massacre at this hearing. But a written statement from first mate James Kelsall was given to the lawyers. Stubbs said it was "absolutely necessary" to throw the enslaved people overboard. He claimed the crew feared all would die otherwise. The insurers argued that Collingwood made a "blunder" by sailing past Jamaica. They said the enslaved people were killed so the owners could claim insurance money. They thought Collingwood did this because he did not want his first slave ship voyage to lose money.

John Lee replied that the enslaved people "perished just as a Cargo of Goods perished." He said they were thrown overboard for the good of the ship. The insurers' lawyers said that killing innocent people could never be justified. They spoke about the humanity of the enslaved people. They said the crew's actions were murder. Historian James Walvin thinks Granville Sharp might have influenced the insurers' legal strategy.

At the hearing, new information came out. It had rained heavily on the ship on the second day of the killings. But a third group of enslaved people was still killed. This led Mansfield to order another trial. He said the rainfall meant that killing those people, after the water shortage was eased, could not be justified. One judge also said this new information made the first jury's decision invalid. The first jury had heard that the water shortage was due to bad ship condition, not captain's errors. Mansfield concluded that the insurers were not responsible for losses caused by the Zong crew's mistakes.

There is no record that another trial on this issue actually happened. Despite Granville Sharp's efforts, no crew member was charged with murder. Even so, the Zong case became known across Britain and beyond. A summary of the appeal was published later in 1831.

Impact on the Anti-Slavery Movement

Granville Sharp worked hard to make people aware of the massacre. He wrote letters to newspapers, navy officials, and the Prime Minister. But he did not get replies from the government officials. Only one London newspaper reported the first Zong trial in March 1783. It gave details of the events. This newspaper article was the first public report of the massacre. It was published almost 18 months after it happened. Little else about the massacre was printed before 1787.

Despite these challenges, Sharp's efforts had some success. In April 1783, he sent a report of the massacre to William Dillwyn, a Quaker. Dillwyn had asked for proof against the slave trade. Soon after, the Quakers decided to start campaigning against slavery. A petition signed by 273 Quakers was sent to Parliament in July 1783. Sharp also wrote to church leaders and people who already supported ending slavery.

The immediate effect of the Zong massacre on public opinion was small. This shows how difficult it was for early anti-slavery activists. But because of Sharp's work, the Zong massacre became an important topic in anti-slavery writings. People like Thomas Clarkson and Olaudah Equiano discussed it. These stories often did not name the ship or captain. This made the abuse seem like it could happen on any slave ship. The Zong killings gave a powerful example of the horrors of the slave trade. This helped the anti-slavery movement in Britain grow much larger in the late 1780s. In 1787, the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded.

Parliament received many requests to end the slave trade. It looked into the issue in 1788. With strong support from Sir William Dolben, who had visited a slave ship, Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act 1788. This was its first law to control the slave trade. It limited the number of enslaved people that could be carried. This was to reduce overcrowding and poor health conditions. The law had to be renewed every year. Dolben led these efforts, often speaking against slavery in Parliament. The Slave Trade Act 1799 made these rules permanent.

Anti-slavery activists, especially William Wilberforce, kept working to end the slave trade. Britain passed the Slave Trade Act 1807. This law stopped the Atlantic slave trade. The Royal Navy then helped stop illegal slave ships at sea. The United States also banned the Atlantic slave trade in 1808.

In 1823, the first Anti-Slavery Society was formed in Britain. It aimed to end slavery across the British Empire. The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 achieved their goal. The Zong massacre was often mentioned in anti-slavery writings in the 1800s. In 1839, Thomas Clarkson published a book about the history of the anti-slavery movement. It included a story of the killings.

Clarkson's book greatly influenced the artist J. M. W. Turner. In 1840, Turner showed a painting called The Slave Ship. It shows a ship from which enslaved people, in chains, have been thrown into the sea. Sharks are eating them. Some details in the painting, like the chains, seem to be from Clarkson's book. The painting was shown at an important time for the anti-slavery movement. The art show opened one month before the first World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. The painting was admired by its owner, John Ruskin. A modern art critic called it one of the best Western artworks about the Atlantic slave trade.

Zong in Modern Culture

The Zong massacre has inspired several books and plays. Fred D'Aguiar's novel Feeding the Ghosts (1997) tells the story of an African who survives being thrown overboard from the Zong. In the novel, the journal of the enslaved person is lost. This shows how African voices about the massacre were often silenced.

Margaret Busby's play An African Cargo was performed in 2007. It was about the massacre and the 1783 trials. It used the real court records and included songs.

M. NourbeSe Philip's 2008 book of poems Zong! is based on the massacre. It uses the court hearing records as its main material. Philip's poems break apart the court document's words. This is a way to question its authority.

An episode of the TV show Garrow's Law (2010) is loosely based on the legal events. The real William Garrow was not involved in the case. Also, the Zong's captain died soon after arriving in Jamaica. So, his appearance in court in the show is fictional.

In 2014–15, David Boxer, an artist from Jamaica, painted Passage: Flotsam and Jetsam III (Zong).

A play by Giles Terera, called The Meaning of Zong, also deals with the massacre and the 1783 trials. It had workshop performances in 2018 and was fully staged in 2022.

"The Ship They Called The Zong" is a short film from 2020. It goes with a poem of the same name. It shows paintings and photos about the Transatlantic slave trade. Some of these show the massacre itself.

The Zong legal case is the main topic of the 2013 British film Belle.

In 2023, Amanda Gorman published a poem called "These Means of Dying." It was inspired by Philip's poem Zong! and used words from the same court report. It was in a newspaper article about a boat disaster in the Mediterranean Sea that killed many migrants.

2007 Abolition Commemorations

In 2007, a memorial stone was put up at Black River, Jamaica. This was near where Zong would have landed. A sailing ship that looked like Zong sailed to Tower Bridge in London in March 2007. This was to remember 200 years since the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. It cost £300,000. The ship had displays about the Zong massacre and the slave trade. It was joined by HMS Northumberland. This navy ship had an exhibition about the Royal Navy's role in stopping the slave trade after 1807.

See also

- Dido Elizabeth Belle (1761–1804), a woman born into slavery but raised as a free woman by Lord Mansfield, her uncle

- Belle, a 2013 film

- La Amistad, a ship involved in an important slavery-related court case in the US

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |