ʻAbdu'l-Bahá facts for kids

Quick facts for kids ʻAbdu'l-Bahá |

|

|---|---|

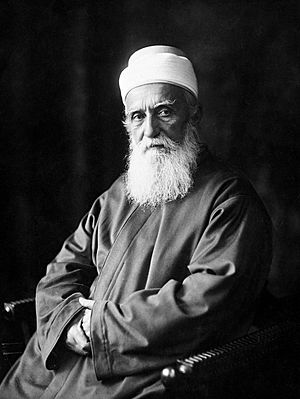

Portrait taken in Paris, 1911

|

|

| Religion | Baháʼí Faith |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | Persian |

| Born | ʻAbbás 23 May 1844 Tehran, Sublime State of Persia |

| Died | 28 November 1921 (aged 77) Haifa, Mandatory Palestine |

| Resting place | Shrine of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 32°48′52.59″N 34°59′14.17″E / 32.8146083°N 34.9872694°E |

| Spouse |

Munírih Khánum (m. 1873)

|

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Shoghi Effendi (grandson) |

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (born ʻAbbás on 23 May 1844 – 28 November 1921) was the oldest son of Baháʼu'lláh. He led the Baháʼí Faith from 1892 until 1921. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá is seen as one of the three main figures of the religion, along with Baháʼu'lláh and the Báb. His writings and talks are very important to Baháʼís.

He was born in Tehran, a city in what is now Iran, into a well-known family. When he was eight, his father was put in prison because of his beliefs. The family lost almost everything and became very poor. His father was sent away from Iran, and the family moved to Baghdad, where they lived for nine years. Later, the Ottoman Empire government moved them to Istanbul, then to Edirne, and finally to the prison-city of ʻAkká (Acre). ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was held there as a prisoner until 1908, when he was 64 years old, and the Young Turk Revolution set him free.

After gaining his freedom, he traveled to Europe and North America. He wanted to share the Baháʼí message beyond the Middle East. However, World War I started in 1914, and he had to stay mostly in Haifa until 1918. After the war, the British took control of the area. They gave him a special honor, making him a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire. This was because he helped prevent a famine (a time when there isn't enough food) after the war.

In 1892, Baháʼu'lláh chose ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in his will to be his successor and the leader of the Baháʼí Faith. Some of his family members disagreed with this choice. But most Baháʼís around the world stayed loyal to him. His Tablets of the Divine Plan encouraged Baháʼís in North America to spread the Baháʼí teachings to new places. His Will and Testament created the plan for how the Baháʼí community would be organized. Many of his writings, prayers, and letters still exist today. His talks with Western Baháʼís show how the religion grew by the late 1890s.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's birth name was ʻAbbás. He preferred the title ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, which means "servant of Bahá." This showed his devotion to his father. Baháʼís often call him "The Master."

Contents

Early Life

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was born in Tehran, Persia (now Iran) on 23 May 1844. He was the oldest son of Baháʼu'lláh and Navváb. He was born on the same night that the Báb announced his mission. As a child, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was influenced by his father's important role in the Bábí Faith. He remembered meeting Táhirih, an important Bábí woman, who would "caress me, and talk to me."

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá had a happy childhood. His family's homes were comfortable and beautiful. He loved playing in the gardens with his younger sister, Bahíyyih. He also had a younger brother, Mihdí. The three children grew up in a privileged and happy home. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá saw his parents helping others, even turning part of their home into a hospital for women and children.

He spent most of his life in exile and prison, so he didn't have a normal school education. At that time, noble children were usually taught at home. They learned about religious texts, speaking well, writing beautifully, and basic math. Most of his learning came from his father. Years later, in 1890, a scholar named Edward Granville Browne said that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was "eloquent of speech" and knew a lot about the holy books of different religions.

When ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was seven, he became very sick with tuberculosis. Everyone thought he would die. Even though he recovered, he would have health problems for the rest of his life.

A major event in his childhood was when his father was imprisoned. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was eight years old. His family lost their wealth and were even attacked in the streets by other children. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá went with his mother to visit his father in the dark prison called the Síyáh-Chál. He said, "I saw a dark, steep place... we heard His [Baháʼu'lláh's]…voice: 'Do not bring him in here'."

Life in Baghdad

Baháʼu'lláh was released from prison but was sent away from his home country. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, then eight years old, went with his father to Baghdad in early 1853. During the journey, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá suffered from frostbite. After a year, Baháʼu'lláh went away by himself to the mountains for two years. During this time, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, his mother, and sister became very close. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was especially close to them. His mother helped a lot with his education.

Even before he was considered an adult (which was 14 in that society), ʻAbdu'l-Bahá took on the job of managing the family's affairs. He spent a lot of time reading and copying the writings of the Báb. He also enjoyed horse riding and became a skilled rider as he grew up.

In 1856, news reached the family that Baháʼu'lláh might be in the mountains. Family and friends went to find him and brought him back to Baghdad. When ʻAbdu'l-Bahá saw his father, he cried and asked, "Why did you leave us?" ʻAbdu'l-Bahá soon became his father's helper and protector. He grew into a young man in Baghdad. People noticed he was "remarkably fine looking" and known for his kindness. As a young man, he often went to mosques to discuss religious topics.

When he was about 15 or 16, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá wrote a long essay for a religious leader. The leader was amazed that someone so young could write such a detailed work. In 1863, in a place called the Garden of Ridván, his father Baháʼu'lláh announced that he was the special person whose coming the Báb had foretold. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá is believed to be the first person Baháʼu'lláh told about his claim.

Istanbul and Adrianople

In 1863, Baháʼu'lláh was ordered to go to Istanbul. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, then 18, went with him on the 110-day trip. It was a difficult journey, and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá helped feed the exiles. Here, his role among the Baháʼís became more important. Baháʼu'lláh praised his son's qualities in a special writing. The family was soon sent away again to Adrianople, and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá went with them. He again suffered from frostbite.

In Adrianople, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was seen as the only comfort for his family, especially his mother. By this time, Baháʼís called him "the Master." Others called him ʻAbbás Effendi, which means "Sir." In Adrianople, Baháʼu'lláh called his son "the Mystery of God." This title means that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá is not a special messenger of God, but someone who perfectly combines human qualities with great knowledge and goodness. Baháʼu'lláh gave his son many other titles, like "Mightiest Branch" and "the Center of the Covenant." ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was very sad when he heard that he and his family might be separated from Baháʼu'lláh. Baháʼís believe he helped make it possible for the family to stay together.

Life in ʻAkká

At 24, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was clearly his father's main helper and a respected member of the Baháʼí community. In 1868, Baháʼu'lláh and his family were sent to the prison city of ʻAkká. People expected the family to die there. Arriving in ʻAkká was very hard. The local people were unfriendly, and his sister and father became very sick. When told that the women had to be carried on men's shoulders to reach the shore, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá found a chair and carried the women himself. He also found medicine and cared for the sick.

The Baháʼís were imprisoned in terrible conditions. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá himself became very ill. However, a kind soldier allowed a doctor to help him. The local people avoided them, and the soldiers treated them badly. The accidental death of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's youngest brother, Mihdí, at age 22, made things even worse. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, full of grief, stayed by his brother's body all night.

Later Years in ʻAkká

Over time, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá slowly took charge of how the small Baháʼí community interacted with the outside world. Through his actions, the people of ʻAkká began to see that the Baháʼís were innocent. Because of this, the prison conditions became easier. Four months after Mihdí's death, the family moved from the prison to the House of ʻAbbúd. The people of ʻAkká started to respect the Baháʼís, especially ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. He arranged for houses to be rented for the family. Later, around 1879, the family moved to the Mansion of Bahjí when an illness caused others to leave the area.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá became very popular in ʻAkká. A lawyer from New York, Myron Henry Phelps, described how "a crowd of human beings...Syrians, Arabs, Ethiopians, and many others" waited to talk to ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. He also wrote a history of the Bábí religion called A Traveller's Narrative in 1886.

Marriage and Family Life

When ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was a young man, many Baháʼís wondered who he would marry. Several young women were considered, but ʻAbdu'l-Bahá didn't seem interested in marriage. On 8 March 1873, at his father's urging, the 28-year-old ʻAbdu'l-Bahá married Fátimih Nahrí of Isfahán (1847–1938). She was 25 and from a well-known family. Fátimih was brought from Persia to ʻAkká after Baháʼu'lláh and his wife wanted her to marry ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. After a long journey, she arrived in 1872. The couple was engaged for about five months before they married. Fátimih later wrote that she fell in love with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá when she first saw him. Baháʼu'lláh gave Fátimih the title Munírih, which means "Luminous."

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and Munírih had nine children. Their first child, a son, died at about age 3. They also lost other children, which caused ʻAbdu'l-Bahá great sadness. The death of his son Husayn Effendi was especially hard, coming after his mother and uncle had also passed away. Their surviving children were all daughters: Ḍíyáʼíyyih K͟hánum (mother of Shoghi Effendi), Túbá K͟hánum, Rúḥá K͟hánum, and Munavvar K͟hánum. Baháʼu'lláh wanted Baháʼís to follow ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's example and move away from having more than one wife. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá chose to have only one wife, which helped establish that having one spouse was the right way for Baháʼís, even though having multiple wives was common at the time.

Leading the Baháʼí Faith

After Baháʼu'lláh passed away on 29 May 1892, his Will and Testament named ʻAbdu'l-Bahá as the leader and interpreter of Baháʼu'lláh's writings.

Baháʼu'lláh wrote in his will: "When the ocean of My presence hath ebbed... turn your faces toward Him Whom God hath purposed, Who hath branched from this Ancient Root." He said this meant ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's half-brother, Muhammad ʻAlí, was also mentioned in the will, but as being under ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Muhammad ʻAlí became jealous and tried to become the leader himself. He wrote to Baháʼís in Iran, secretly at first, trying to make them doubt ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Most Baháʼís followed ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, but a few followed Muhammad ʻAlí.

Muhammad ʻAlí and others began to openly accuse ʻAbdu'l-Bahá of taking too much power. They said he thought he was a special messenger of God, like Baháʼu'lláh. To show that these accusations were false, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá wrote to Baháʼís in the West. He said he should be known as "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá," which means "Servant of Bahá." This made it clear that he was not a messenger of God, but only a servant.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left a Will and Testament that set up the way the Baháʼí community would be managed. He named Shoghi Effendi as the first Guardian of the religion. Muhammad ʻAlí and his family had little impact on most Baháʼís. In the ʻAkká area, only a few families followed Muhammad ʻAlí, and they soon blended into Muslim society.

First Western Visitors

By the end of 1898, Western Baháʼís began to visit ʻAkká to see ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. This was the first time Baháʼís from the West met him. The first group arrived in 1898. Most of them were young women from high society in America. These Western visitors made the authorities suspicious, and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's imprisonment became stricter.

Over the next ten years, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in touch with Baháʼís worldwide, helping them teach the religion. Important visitors included May Ellis Bolles, Thomas Breakwell, and Laura Clifford Barney. Laura Clifford Barney asked ʻAbdu'l-Bahá many questions over several years. Her questions and his answers became the book Some Answered Questions.

Leading the Faith, 1901–1912

In the late 1800s, while still a prisoner, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arranged for the remains of the Báb to be brought from Iran to Palestine. He then bought land on Mount Carmel, as Baháʼu'lláh had instructed, to build the Shrine of the Báb. This project took another 10 years. As more visitors came, Muhammad ʻAlí worked with the Ottoman authorities to make ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's imprisonment stricter again in August 1901. However, by 1902, the situation eased because the Governor of ʻAkká supported ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Visitors could come again, but ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was still confined to the city.

From 1902 to 1904, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá also started two other projects. He began restoring the House of the Báb in Shiraz, Iran. He also started building the first Baháʼí House of Worship in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan.

During this time, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá talked with some Young Turks who were against the rule of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. He wanted to share Baháʼí ideas about freedom, equality, and uniting humanity. He said Baháʼís "seek freedom and love liberty, hope for equality, are well-wishers of humanity."

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá also met Muhammad Abduh, an important figure in Islamic reform, in Beirut. Both men were against the Ottoman religious leaders and wanted religious change.

Because of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's activities and accusations against him, a group questioned him in 1905. He was almost sent away to a distant place. In response, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá wrote to the Sultan, explaining that his followers did not get involved in politics. The next few years in ʻAkká were calmer, and visitors could come. By 1909, the Shrine of the Báb was finished.

Journeys to the West

The Young Turks revolution in 1908 freed all political prisoners in the Ottoman Empire, including ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. His first act was to visit the Shrine of Baháʼu'lláh in Bahji. He soon moved to Haifa, near the Shrine of the Báb. In 1910, now free to travel, he began a three-year journey to Egypt, Europe, and North America to share the Baháʼí message.

From August to December 1911, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá visited cities in Europe, including London, Bristol, and Paris. He wanted to support the Baháʼí communities there and spread his father's teachings.

The next year, he made a longer trip to the United States and Canada. He arrived in New York City on 11 April 1912. He had been offered a trip on the RMS Titanic but chose to travel on a slower ship. He told Baháʼís to "Donate this to charity" instead. After hearing that the Titanic had sunk, he said, "I was asked to sail upon the Titanic, but my heart did not prompt me to do so." He spent most of his time in New York but also visited Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Boston. In August, he traveled to New Hampshire, Maine, and Montreal (his only visit to Canada). He then went west to San Francisco and Los Angeles before returning east. On 5 December 1912, he sailed back to Europe.

During his visit to North America, he spoke at many places and met hundreds of people. In his talks, he shared Baháʼí principles like the oneness of God, the unity of religions, the oneness of humanity, equality of women and men, world peace, and fairness in money matters. He insisted that all his meetings be open to people of all races.

His visit was covered in many newspaper articles. In Boston, reporters asked why he came to America. He said he came to talk about peace and that just giving warnings was not enough. His visit to Montreal also received a lot of newspaper attention. Headlines included "Persian Teacher to Preach Peace" and "Apostle of Peace Meets Socialists."

Back in Europe, he visited London, Paris, and Vienna. Finally, on 12 June 1913, he returned to Egypt. He stayed there for six months before going back to Haifa.

Final Years (1914–1921)

During World War I (1914–1918), ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in Palestine and could not travel. He wrote some letters, including the Tablets of the Divine Plan. These were 14 letters to the Baháʼís of North America. They told the North American Baháʼís that they had an important role in spreading the religion around the world.

Haifa was in danger of being bombed by the Allied forces. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and other Baháʼís temporarily moved to the hills east of ʻAkká for safety.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was also threatened by Cemal Paşa, an Ottoman military leader. He wanted to harm ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and destroy Baháʼí properties. However, the British army, led by General Allenby, quickly defeated the Turkish forces in Palestine before any harm came to the Baháʼís. The war ended less than two months later.

After the War

After World War I, the unfriendly Ottoman authorities were replaced by the more friendly British Mandate. This allowed Baháʼís to communicate more, visitors to come, and the Baháʼí World Centre to grow. During this time, the Baháʼí Faith expanded in places like Egypt, Iran, and North America, guided by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.

The end of the war brought new political changes that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá commented on. The League of Nations was formed in 1920. This was the first time countries tried to work together for worldwide peace. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá had written in 1875 about the need for a "Union of the nations of the world." He praised the League of Nations as a step towards this goal. However, he also said it could not bring "Universal Peace" because it didn't include all nations and had little power over its members.

Around the same time, the British supported the immigration of Jews to Palestine. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá saw this as a fulfillment of prophecy. He encouraged the Zionists to develop the land and "elevate the country for all its inhabitants."

The war also caused a famine in the region. In 1901, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá had bought land near the Jordan river. By 1907, many Baháʼís from Iran were farming there. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá received a share of their harvest. In 1917, with the war still going on, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá received a large amount of wheat from these crops. He also bought other available wheat and sent it all to Haifa. The wheat arrived just after the British took control of Palestine. It was given out widely to help stop the famine. For this help in preventing starvation in Northern Palestine, he received the honor of Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire. This ceremony took place on 27 April 1920. He was later visited by important figures like General Allenby and King Faisal.

Death and Funeral

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá passed away on Monday, 28 November 1921.

Important leaders, like Winston Churchill, sent messages of sympathy to the Baháʼí community. He was buried in the front room of the Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel. His burial there is meant to be temporary. A special building for him, called the Shrine of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, is planned to be built nearby.

His Legacy

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left a Will and Testament, written between 1901 and 1908. It was addressed to Shoghi Effendi, who was only a young boy at the time. The will named Shoghi Effendi as the first Guardian of the religion. This was a leadership role that could explain the holy writings. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá told all Baháʼís to follow him and promised him divine protection. The will also repeated his teachings, such as the importance of teaching the faith, showing good qualities, being friendly with everyone, and avoiding those who caused disunity. Most Baháʼís around the world accepted the will.

Shoghi Effendi later named nineteen Baháʼís as special followers of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.

During his lifetime, some Baháʼís were unsure about his exact role compared to Baháʼu'lláh. Some newspapers even called him a Baháʼí prophet. Shoghi Effendi later clarified that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was one of the three "Central Figures" of the Baháʼí Faith. He called him the "Perfect example" of the teachings. Shoghi Effendi also wrote that no one would be equal to ʻAbdu'l-Bahá for the next 1000 years of the Baháʼí Faith.

Appearance and Personality

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was described as handsome and looked a lot like his mother. As an adult, he was of medium height but seemed taller. He had long dark hair, gray eyes, fair skin, and a distinct nose.

After Baháʼu'lláh died, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá began to show signs of aging. By the late 1890s, his hair was white, and he had deep lines on his face. When he was young, he was athletic and enjoyed archery, horseback riding, and swimming. Even later in life, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed active, taking long walks in Haifa and Acre.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was a very important person for Baháʼís during his life, and he still influences the Baháʼí community today. Baháʼís see him as the perfect example of his father's teachings and try to be like him. Stories about him are often used to teach about good behavior and how to get along with others. He was known for his strong personality, kindness, generosity, and strength when facing difficulties.

Even people who were against the Baháʼí Faith were sometimes impressed after meeting him. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was known for helping the poor and the sick. His generosity was so great that his own family sometimes worried they would have nothing left. He cared deeply about people's feelings. He once said, "I am your father...and you must be glad and rejoice, for I love you exceedingly." Historical accounts say he had a good sense of humor and was relaxed and informal. He was open about his personal sadness, like losing his children and the hardships he faced as a prisoner, which made him even more popular.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá guided the Baháʼí community carefully. He allowed people to understand the Baháʼí teachings in different ways, as long as it didn't go against the main ideas. However, he did remove members from the religion if he felt they were challenging his leadership and causing problems. He was deeply affected by times when Baháʼís were persecuted. He wrote personal letters to the families of those who had been killed for their beliefs.

Writings

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá wrote an estimated 27,000 letters and other writings. Only a small part of these have been translated into English. His works can be divided into two groups: his own writings and his talks and speeches written down by others.

The first group includes:

- The Secret of Divine Civilization, written before 1875.

- A Traveller's Narrative, written around 1886.

- Sermon on the Art of Governance, written in 1893.

- Memorials of the Faithful.

- Many letters written to different people, including the Tablet to Auguste-Henri Forel.

- The Secret of Divine Civilization and Sermon on the Art of Governance were widely shared without his name on them.

The second group includes:

- Some Answered Questions, which is an English translation of talks he had with Laura Barney.

- Paris Talks, ʻAbdu'l-Baha in London, and Promulgation of Universal Peace. These are talks he gave in Paris, London, and the United States.

Here is a list of some of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's many books, letters, and talks:

- Foundations of World Unity

- Light of the World: Selected Tablets of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá

- Memorials of the Faithful

- Paris Talks

- Secret of Divine Civilization

- Some Answered Questions

- Tablets of the Divine Plan

- Tablet to Auguste-Henri Forel

- Tablet to The Hague

- Will and Testament of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá

- Promulgation of Universal Peace

- Selections from the Writings of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá

- Divine Philosophy

- Treatise on Politics / Sermon on the Art of Governance

See also

In Spanish: `Abdu'l-Bahá para niños

In Spanish: `Abdu'l-Bahá para niños

- Baháʼu'lláh's family

- Mírzá Mihdí

- Ásíyih Khánum

- Bahíyyih Khánum

- Munirih Khánum

- Shoghi Effendi

- House of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |