1939 American Karakoram expedition to K2 facts for kids

The 1939 American Karakoram expedition to K2 was an attempt by American climbers to reach the top of K2. K2 is the second-highest mountain in the world. This was their second try, after a scouting trip in 1938.

The expedition leader, Fritz Wiessner, and his climbing partner, Pasang Dawa Lama, got very close to the summit. They were only about 800 feet (240 meters) from the top using a tough path called the Abruzzi Ridge. Wiessner did most of the difficult climbing.

Sadly, things went wrong. One team member, Dudley Wolfe, was left alone high on the mountain. His companions had gone back to base camp. Three attempts were made to rescue Wolfe. On the second try, three Sherpas reached him after he had been alone for a week at over 24,000 feet (7,300 meters). But he refused to come down. Two days later, the Sherpas tried again, but they were never seen again. The final rescue effort was stopped when everyone lost hope for the four climbers.

These deaths and the way the expedition was organized caused a lot of arguments among the team members and people back in America. At first, many blamed Wiessner. Later, some criticism shifted to another team member, Jack Durrance. When Durrance's diary was finally shared in 1989, it seemed the main problems were with the deputy leader, Tony Cromwell, and Wiessner himself.

In 1961, writer Fosco Maraini called this expedition "one of the worst tragedies in the climbing history of the Himalaya."

Contents

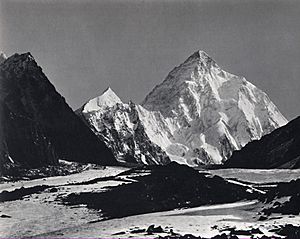

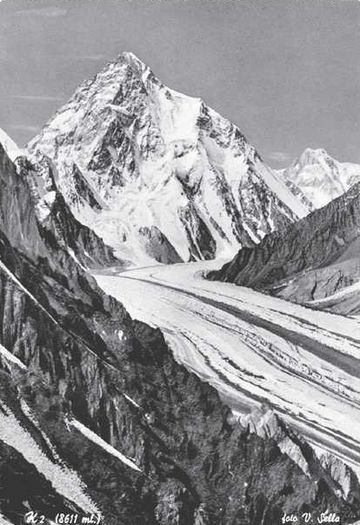

About K2

K2 is a huge mountain located on the border between what was then British India (now Pakistan) and China. It stands at 28,251 feet (8,611 meters) tall. This makes it the highest point in the Karakoram mountain range and the second-highest mountain in the entire world.

For many years, climbers tried and failed to reach K2's summit. In 1909, an expedition led by the Duke of the Abruzzi reached about 20,500 feet (6,250 meters) on the southeast ridge. They thought the mountain was too hard to climb. This path later became known as the Abruzzi Ridge and is now the most common way to climb K2.

The 1938 American Expedition

The American Alpine Club (AAC) wanted to climb K2. In 1937, Fritz Wiessner suggested an expedition. The AAC got permission for a try in 1938, and another in 1939 if the first one failed.

Charlie Houston led the 1938 expedition. He was an experienced climber who had climbed Mount Foraker in Alaska and Nanda Devi in the Himalayas. His team explored different routes up K2. They chose the Abruzzi Ridge and made good progress. By July 19, 1938, they reached 24,700 feet (7,529 meters). However, they were running low on supplies, and the monsoon season was coming.

Houston and Paul Petzoldt made one last push. On July 21, they reached about 26,000 feet (7,925 meters). They found a good spot for a higher camp and a clear path to the summit.

The 1938 expedition was a success. They had explored the Abruzzi Ridge, found good camp spots, and identified the hardest part of the climb: the House Chimney at 22,000 feet (6,705 meters). This made the way clear for the 1939 expedition.

Fritz Wiessner's Role

Fritz Wiessner was a 39-year-old German climber. He had climbed many difficult routes in the Alps. In 1932, he joined an expedition to Nanga Parbat. From there, he saw K2, and it became his main goal.

Wiessner moved to the United States and became a U.S. citizen in 1935. He was known for introducing advanced climbing techniques. In 1936, he and Bill House were the first to climb Mount Waddington in Canada. By 1938, he was the top American climber with experience on very high mountains. He was the clear choice to lead the 1939 K2 expedition.

Planning the 1939 Expedition

In late 1938, the American economy was not doing well. It was hard to find money for the 1939 expedition. So, Wiessner had to choose climbers who could pay their own way. The expedition would last up to six months. Few experienced climbers were available or could afford it. The total cost was about US$17,500, or US$2,500 per person.

Team Members

The team had six climbers and nine Sherpas. Porters were hired along the way. Many of the most skilled climbers could not join.

- Tony Cromwell was Wiessner's deputy. He was wealthy and loved mountaineering, but he usually hired guides and didn't do very challenging climbs. He was 44 and didn't plan to climb very high on K2.

- Chappell Cranmer (20 years old) was a college student. He had some climbing experience but was still learning.

- George Sheldon was Cranmer's classmate. He was excited but had very little climbing experience.

- Dudley Wolfe (born 1896) came from a very rich family. He was strong and could handle tough conditions, but he was clumsy and often needed guides. He paid for many of the expedition's costs.

- Jack Durrance (26 years old) joined at the last minute. He had learned skiing and rock climbing in Germany. He was a mountain climber and guide in the Tetons. He was the official expedition doctor, even though he hadn't started medical school yet. He felt he and most others on the team were not experienced enough.

The non-climbing team members included Lieutenant George Trench (British officer), Chandra Pandit (interpreter), and Noor (cook). Pasang Kikuli was the sirdar (head Sherpa). He was the most experienced high-altitude climber in the world, having been on the 1936 Nanda Devi climb and the 1938 K2 expedition.

Equipment

Wiessner and Wolfe bought climbing gear in Europe, where there was more choice. They got strong, heavy tents, inflatable mattresses, stoves, and warm sleeping bags. They used Italian hemp ropes, which became heavy and hard to use when wet and frozen. Dehydrated food was limited, so most food was canned. They didn't have padded clothes and didn't get good boots or snow goggles for the Sherpas and porters. Radios and oxygen systems were available but were heavy and unreliable, so they didn't take them.

Journey to K2

The team traveled by ship to India, then by train to Rawalpindi, and by car to Srinagar. In Srinagar, they stayed at a skiing hut at 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) to get used to the high altitude. They met the Sherpas there.

On May 2, they started their trek to K2. The road ended at Wayil, about 330 miles (530 kilometers) from the mountain. They walked and used ponies, changing porters every few days. They crossed the Indus River and entered the Karakoram range. Cromwell noted how barren and tough the land was. They passed through small villages, eventually reaching Askole, the last village before the wilderness. On May 22, they left Askole with 123 porters.

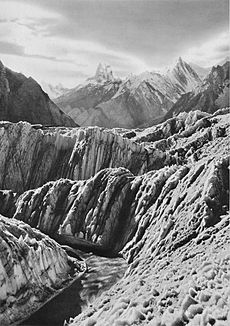

On May 26, they reached the Baltoro Glacier at 11,500 feet (3,500 meters). They faced a porters' strike and some porters got snow blindness. On May 31, they reached Concordia, where they could finally see K2. Base Camp was set up at 16,500 feet (5,030 meters). Most porters were sent back, with instructions to return on July 23. This gave them 53 days to climb the mountain.

The next day, Chappell Cranmer became very ill, likely with pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs). Durrance, despite his lack of medical training, helped him recover. Cranmer could no longer climb high on the mountain.

Climbing K2

The expedition used the same camp locations as the 1938 team. Four Sherpas had been on the previous expedition, which was helpful.

| Locations of camps on mountain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camp | Altitude feet |

Altitude metres |

Status | Location |

| Base | 16,500 | 5030 | major | Godwin-Austen Glacier |

| I | 18,600 | 5670 | Abruzzi Ridge | |

| II | 19,300 | 5882 | major | sheltered spot on Ridge |

| III | 20,700 | 6310 | cache (site vulnerable to falling rocks) | |

| IV | 21,500 | 6553 | major | Red Rocks, below House Chimney |

| V | 22,000 | 6705 | right above House Chimney, start of sharp part of Ridge | |

| VI | 23,400 | 7130 | major | base of Black Tower (or pyramid) |

| VII | 24,700 | 7529 | major | plateau above Ridge and ice traverse |

| VIII | 25,300 | 7711 | assault | hollow on plateau |

| IX | 26,050 | 7940 | assault | south of summit cliffs, below the couloir later called the "Bottleneck" |

| high point |

27,450 | 8370 | no camp |

turned back at start of summit snow plateau |

| Summit | 28,251 | 8611 | – | summit not reached |

Wiessner saw himself as the main climber and leader. Cromwell, who was not planning to climb high, was the deputy. This gave Wiessner too much control. Cranmer was sick, and Durrance was waiting for his proper boots. The Abruzzi Ridge is dangerous in bad weather. Strong winds and falling rocks are big problems.

To Camp IV

On June 5, they carried supplies to Camp I. Camp I was set up on June 8. The next day, Wiessner, Durrance, and Pasang Kikuli reached Camp II, which became a main storage area for food and gear.

Wolfe was clumsy but hardworking and well-liked. He became closer to Wiessner, possibly because he was paying for much of the expedition.

On June 14, Wiessner went back to Base Camp, leaving Cromwell in charge up to Camp IV. Wiessner found Cranmer feeling better. Back at Camp II on June 17, Wiessner saw that the team had not made much progress. Cromwell was a timid leader. Wiessner took over the climbing lead again and continued to lead for the rest of the summit attempt.

The Storm

From June 21, a bad storm lasted for eight days. At Camp IV, the temperature dropped to -2°F (-19°C). At Camp II, winds reached 80 mph (130 km/h). On June 28, Durrance finally got his boots. The storm stopped on June 29. Wiessner and Wolfe still wanted to reach the summit, but the rest of the team had lost their spirit.

On July 1, Durrance sent a note to Wiessner at Camp V, saying his boots had arrived. Wiessner seemed to misunderstand and replied, "I am very disappointed in you..." This created a big split between Wiessner and the rest of the climbers, except for Wolfe. After carrying supplies in another storm, Cromwell was hurt, and Sheldon got frostbitten toes. Sheldon was sent to Base Camp and stayed there.

Wiessner's High Climb

On June 30, Wiessner climbed the House Chimney and set up ropes. The next day, he helped Wolfe and another Sherpa climb the cliffs, and they set up Camp V. After another three-day storm, Wiessner and the Sherpas climbed to Camp VI. On July 6, they climbed the Black Tower to reach Camp VII at 24,700 feet (7,529 meters). Wolfe stayed at Camp V. No new supplies had been carried up, so Wiessner went all the way down to Camp II to check on things.

Wiessner and Wolfe to Camp VIII

Durrance and the others were surprised by the progress high on the mountain. They had only made two trips to Camp III. Durrance, Cromwell, Trench, and six Sherpas started climbing again. At Camp V, Durrance found Wolfe's feet were frostbitten. But Wiessner let Wolfe continue. On July 13, Durrance became exhausted and went down to Camp VI. Wiessner, Wolfe, and three Sherpas stayed at Camp VII. The next day, the higher group reached Camp VIII. They had reached Camp VIII in the same amount of time as the 1938 expedition, but their supply lines were very stretched.

Durrance was completely exhausted from descending to Camp VI. He was suffering from hypoxia (lack of oxygen) and possibly fluid in his lungs or brain. He told Sherpas to restock the higher camps. He then went down to Camp II, where he found Cromwell and Trench doing nothing. There was no longer a connection between the summit team and those below. Later, there would be many arguments about whether the team abandoned Wiessner or if he abandoned them.

Summit Attempts and Problems

A big problem had developed. Wiessner, Wolfe, and Pasang Lama were at Camp VIII, ready to try for the summit. They believed supplies were being brought up to them. But at Base Camp and Camp II, the others felt they had little to do. At Camps VI and VII, four Sherpas were left alone with unclear instructions.

Wiessner and Pasang Lama's Summit Attempts (July 17–21)

From Camp VIII, Wiessner and Pasang Lama planned their final push, not knowing that their supplies were almost gone. They started climbing on July 17. Wiessner had been above 22,000 feet (6,700 meters) for 24 days, and Wolfe for 26 days. (At high altitudes, the human body and mind get weaker over time.)

Wolfe couldn't go further, so he returned to Camp VIII. Wiessner and Pasang Lama moved Camp IX higher. Wiessner thought they had plenty of supplies at all the camps below. The weather was perfect, and the summit was only 2,200 feet (670 meters) above them.

On July 19, they started their summit attempt late, at 9:00 AM. They faced a choice: a dangerous path called the "Bottleneck" or a very difficult rock climb. Wiessner chose the rock climb, which took nine hours. It was incredibly hard at that altitude. (This rock climb has never been repeated.) They were at about 27,450 feet (8,370 meters), with only an easy 800-foot (240-meter) snow plateau to the top. Wiessner wanted to keep going through the night, but Pasang Lama refused. Wiessner agreed to turn back. Pasang Lama lost his crampons on the way down. They reached Camp IX at 2:30 AM, very tired.

Disappointed that no supplies had arrived, they rested. On July 21, they tried for the summit again, this time using the "Bottleneck" route. But the snow was bad, and without crampons, they couldn't make progress. They returned to Camp IX.

Sherpas at Camps VI and VII

The four Sherpas left at Camps VI and VII did not carry supplies higher. Two of them, Tse Tendrup and Pasang Kitar, even went down to Camp IV. On July 18, Pasang Kikuli and Dawa Thondup arrived from below and told them to go back up. They only reached Camp VII. Tse Tendrup went a bit higher but didn't dare go alone. He shouted but got no reply. Seeing signs of avalanches, he wrongly thought the climbers above had died.

Back at Camp VII, Tse Tendrup convinced the other Sherpas that everyone higher up was dead. With only three days before they were supposed to go home, they decided to go down. They also cleared Camps VII and VI as they went. By July 23, they were back at Base Camp.

At Base Camp and Camp II

On July 18, Cromwell had sent a note to Durrance, asking him to bring down tents and sleeping bags from Camp IV and below. Porters were due back on July 23 for the return journey. Durrance sent Sherpas to clear the camps and moved equipment from Camp II to Base Camp. When Pasang Kikuli told Durrance about Camp VIII being set up, Durrance was happy.

Sheldon and Cranmer decided to leave early to study geology. This left only Cromwell, Durrance, and Trench with three Sherpas. They saw Camp VI had been taken down on July 21. They expected Wiessner's group back by July 23. But only the four intermediate Sherpas arrived that day. No one had seen or heard from Wiessner's party since July 14.

Wiessner and Pasang Lama's Descent

On July 22, Wiessner and Pasang Lama went down to Camp VIII to get supplies. They were horrified to find Wolfe alone. He had run out of matches and couldn't cook or melt ice. No supplies had arrived. Wiessner didn't realize that people below might think he was in trouble after nine days.

All three went down to Camp VII. Wolfe was so clumsy that they had a serious fall while roped together, nearly falling off the mountain. Pasang Lama was injured, and Wolfe lost his sleeping bag. At Camp VII, they found no new supplies, collapsed tents, and scattered food. Luckily, there were stoves and fuel.

Wiessner decided Wolfe should stay at Camp VII while he and Pasang Lama went down for supplies, still planning another summit attempt. Wiessner later said Wolfe wanted to stay. But after so long at high altitude, they might not have been thinking clearly. Wiessner and Pasang Lama went down, finding little food and no sleeping bags, until they reached Base Camp on July 24. They were completely exhausted. Wiessner was furious, accusing Cromwell and Tendrup of trying to harm them. Cromwell, in turn, accused Wiessner of abandoning Wolfe. They became enemies for life. Durrance kept quiet about his role in clearing the lower camps.

Search for Wolfe

First Rescue Attempt

With Base Camp being packed up, Durrance tried to rescue Wolfe from Camp VII. On July 25, Durrance set off with three Sherpas. Wiessner thought Durrance might even try for the summit with him. But Durrance's only goal was to rescue Wolfe. Durrance's group reached Camp IV in two days. Only two Sherpas were strong enough to continue to Camp VI. Durrance and Dawa Thondup returned to Base Camp on July 27.

Second Rescue Attempt

On July 28, Pasang Kikuli and Tsering Norbu left Base Camp at 6:00 AM. They reached Camp IV by noon and Camp VI by the end of the day. This was an amazing speed.

Tsering Norbu stayed at Camp VI. Pasang Kikuli, Pasang Kitar, and Phinsoo reached Wolfe at noon on July 29. (Wolfe had been above 22,000 feet for 38 days and at 25,000 feet for 16 days without extra oxygen. No one else had done this before.) At Camp VII, things were terrible. Wolfe was very tired and didn't care about the letters they brought. He refused to go down, telling them to come back tomorrow. The Sherpas were stuck at Camp VI by a storm. On July 31, the same three Sherpas tried again. Pasang Kikuli, Pasang Kitar, Phinsoo, and Wolfe were never seen alive again.

Third Rescue Attempt

Tsering Norbu waited two days before coming down from Camp VI. He reached Base Camp early in the afternoon. Durrance wrote, "The Sherpas are certain something awful has happened." Wiessner didn't believe it. There was no one fit enough left, but Wiessner set off on August 3 with Tsering Norbu and Dawa Thondup. A storm hit. On August 7, Tsering Norbu said he was wrong before: they had found Wolfe with no food at Camp VII. Even Wiessner now lost all hope. Wolfe and the three Sherpa rescuers were all dead. The rescue team managed to get back to base, but they were in a very bad state.

Return Home

Sheldon and Cranmer were the first to return home. They had left before the tragedy began.

Wiessner and Durrance followed their original route back. At Askole, they crossed the Braldu River and went over the Skoro La pass to reach Shigar. There, they started writing their report on the expedition. They seemed to agree on what happened. They sent reports to The Times of India. On August 27, they met Cromwell. According to Durrance's diary, Cromwell was furious when he saw the report. He shouted that Wiessner had caused the deaths of Wolfe and the Sherpas. Cromwell and Trench had already been in Srinagar, sharing their views with the British community. Cromwell had also sent a message to the AAC about the expedition's failure.

On August 28, when they reached Srinagar, the final report was ready. This report, along with letters from Cromwell and Trench to the AAC, caused major arguments.

Aftermath in Srinagar

Durrance decided not to complain about Wiessner's leadership and kept quiet until after Wiessner's death. D.M. Fraser, a British official, stopped Cromwell's and Trench's letters from being sent, but he read them to Edward Groth, the US Consulate General. Both letters then disappeared. At Fraser's request, Groth met with Wiessner and Durrance for seven hours. Groth then wrote an official report for Washington. He thought Trench's letter was not important and Cromwell's accusations were angry and exaggerated, though they had some truth.

Wiessner's Report

Wiessner's report to the AAC described the main events. He praised Pasang Kikuli and Tsering Norbu. He said Wolfe was left at Camp VII because he and Pasang Lama planned to return with supplies. But the lower camps had been cleared, so they couldn't go back up. He didn't blame anyone, saying conditions were bad and people got sick and tired.

Groth's Report

Groth's report to the US Secretary of State included Wiessner's report. Groth's report was not made public. He thought there were personality problems, possibly because a German leader was leading American climbers. He felt Wiessner was a good climber but too forceful. He also thought the Americans didn't try hard enough to understand him. Groth believed the accident was due to many things, not just Wiessner. He thought Wiessner should have chosen team members more carefully. He also wondered if Wolfe's money made Wiessner let him climb too high. He praised the Sherpas who tried to rescue Wolfe. He criticized Cromwell and Trench for returning early.

Back in America

Wiessner returned to America by ship. Durrance stayed in India for several weeks and came home later. Back in America, Cromwell again accused Wiessner of causing Wolfe's death. Wiessner also gave an interview where he said that on high mountains, like in war, you must expect people to get hurt or die.

A big public argument started. People took sides, but many criticized Wiessner for leaving Wolfe. These were the first deaths on an American climbing trip overseas, and there was a lot of blame. To avoid a split among its members, the American Alpine Club set up a committee. Their report simply said that the expedition members themselves knew best what happened. Wiessner and Cromwell both resigned from the AAC.

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |